Abstract

Recent genomic data have revealed multiple interactions between Neanderthals and modern humans1, but there is currently little genetic evidence regarding Neanderthal behaviour, diet, or disease. Here we describe the shotgun-sequencing of ancient DNA from five specimens of Neanderthal calcified dental plaque (calculus) and the characterization of regional differences in Neanderthal ecology. At Spy cave, Belgium, Neanderthal diet was heavily meat based and included woolly rhinoceros and wild sheep (mouflon), characteristic of a steppe environment. In contrast, no meat was detected in the diet of Neanderthals from El Sidrón cave, Spain, and dietary components of mushrooms, pine nuts, and moss reflected forest gathering2,3. Differences in diet were also linked to an overall shift in the oral bacterial community (microbiota) and suggested that meat consumption contributed to substantial variation within Neanderthal microbiota. Evidence for self-medication was detected in an El Sidrón Neanderthal with a dental abscess4 and a chronic gastrointestinal pathogen (Enterocytozoon bieneusi). Metagenomic data from this individual also contained a nearly complete genome of the archaeal commensal Methanobrevibacter oralis (10.2× depth of coverage)—the oldest draft microbial genome generated to date, at around 48,000 years old. DNA preserved within dental calculus represents a notable source of information about the behaviour and health of ancient hominin specimens, as well as a unique system that is useful for the study of long-term microbial evolution.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

We are sorry, but there is no personal subscription option available for your country.

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Green, R. E. et al. A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome. Science 328, 710–722 (2010)

Fiorenza, L. et al. Molar macrowear reveals Neanderthal eco-geographic dietary variation. PLoS One 6, e14769 (2011)

El Zaatari, S., Grine, F. E., Ungar, P. S. & Hublin, J.-J. Neandertal versus modern human dietary responses to climatic fluctuations. PLoS One 11, e0153277 (2016)

Rosas, A. et al. Paleobiology and comparative morphology of a late Neandertal sample from El Sidron, Asturias, Spain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 19266–19271 (2006)

Higham, T. et al. The timing and spatiotemporal patterning of Neanderthal disappearance. Nature 512, 306–309 (2014)

Richards, M. P. & Trinkaus, E. Isotopic evidence for the diets of European Neanderthals and early modern humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 16034–16039 (2009)

Bocherens, H., Drucker, D. G., Billiou, D., Patou-Mathis, M. & Vandermeersch, B. Isotopic evidence for diet and subsistence pattern of the Saint-Césaire I Neanderthal: review and use of a multi-source mixing model. J. Hum. Evol. 49, 71–87 (2005)

Hardy, K. et al. Neanderthal medics? Evidence for food, cooking, and medicinal plants entrapped in dental calculus. Naturwissenschaften 99, 617–626 (2012)

Fu, Q. et al. An early modern human from Romania with a recent Neanderthal ancestor. Nature 524, 216–219 (2015)

Weyrich, L. S., Dobney, K. & Cooper, A. Ancient DNA analysis of dental calculus. J. Hum. Evol. 79, 119–124 (2015)

Adler, C. J. et al. Sequencing ancient calcified dental plaque shows changes in oral microbiota with dietary shifts of the Neolithic and Industrial revolutions. Nat. Genet. 45, 450–455, e1 (2013)

Warinner, C. et al. Pathogens and host immunity in the ancient human oral cavity. Nat. Genet. 46, 336–344 (2014)

Ziesemer, K. A. et al. Intrinsic challenges in ancient microbiome reconstruction using 16S rRNA gene amplification. Sci. Rep. 5, 16498 (2015)

Meyer, F. et al. The metagenomics RAST server—a public resource for the automatic phylogenetic and functional analysis of metagenomes. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 386 (2008)

Herbig, A. et al. MALT: fast alignment and analysis of metagenomic DNA sequence data applied to the Tyrolean Iceman. Preprint at http://biorxiv.org/content/early/2016/04/27/050559 (2016)

Germonpré, M., Udrescu, M. & Fiers, E. The fossil mammals of Spy. Anthropologica et Præhistorica 123/2012, 298–327 (2013)

Crégut-bonnoure, E. Nouvelles données paléogéographiques et chronologiques sur les Caprinae (Mammalia, Bovidae) du Pléistocène moyen et supérieur d’Europe. Euskomedia 57, 205–219 (2005)

Patou-Mathis, M. Neanderthal subsistence behaviours in Europe. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 10, 379–395 (2000)

Naito, Y. I. et al. Ecological niche of Neanderthals from Spy Cave revealed by nitrogen isotopes of individual amino acids in collagen. J. Hum. Evol. 93, 82–90 (2016)

O’Regan, H. J., Lamb, A. L. & Wilkinson, D. M. The missing mushrooms: searching for fungi in ancient human dietary analysis. J. Archaeol. Sci. 75, 139–143 (2016)

Tumwine, J. K. et al. Enterocytozoon bieneusi among children with diarrhea attending Mulago Hospital in Uganda. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 67, 299–303 (2002)

Leonard, W. R. & Crawford, M. H. The Human Biology of Pastoral Populations (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2002)

Muegge, B. D. et al. Diet drives convergence in gut microbiome functions across mammalian phylogeny and within humans. Science 332, 970–974 (2011)

Marsh, P. D. & Bradshaw, D. J. Dental plaque as a biofilm. J. Ind. Microbiol. 15, 169–175 (1995)

Signat, B., Roques, C., Poulet, P. & Duffaut, D. Role of Fusobacterium nucleatum in periodontal health and disease. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 13, 25–36 (2011)

Cho, I. & Blaser, M. J. The human microbiome: at the interface of health and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 260–270 (2012)

Topic´, B., Rašc´ic´-Konjhodžic´, H. & Cižek Sajko, M. Periodontal disease and dental caries from Krapina Neanderthal to contemporary man—skeletal studies. Acta Med. Acad. 41, 119–130 (2012)

Wood, R. E. et al. A new date for the Neanderthals from El Sidrón Cave (Asturias, Northern Spain)*. Archaeometry 55, 148–158 (2013)

Stringer, C. The origin and evolution of Homo sapiens. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 371, 20150237 (2016)

Sankararaman, S., Patterson, N., Li, H., Pääbo, S. & Reich, D. The date of interbreeding between Neandertals and modern humans. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002947 (2012)

Brotherton, P. et al. Neolithic mitochondrial haplogroup H genomes and the genetic origins of Europeans. Nat. Commun. 4, 1764 (2013)

Caporaso, J. G. et al. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. ISME J. 6, 1621–1624 (2012)

Meyer, M. & Kircher, M. Illumina sequencing library preparation for highly multiplexed _target capture and sequencing. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2010, pdb.prot5448 (2010)

Aronesty, E. ea-utils: command-line tools for processing biological sequencing data. (Expression Analysis, Durham, 2011)

Caporaso, J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7, 335–336 (2010)

DeSantis, T. Z. et al. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 5069–5072 (2006)

Lindgreen, S. AdapterRemoval: easy cleaning of next-generation sequencing reads. BMC Res. Notes 5, 337 (2012)

Segata, N. et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 12, R60 (2011)

Aziz, R. K. et al. The RAST server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics 9, 75 (2008)

Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 12, 59–60 (2015)

Huson, D. H., Mitra, S., Ruscheweyh, H.-J., Weber, N. & Schuster, S. C. Integrative analysis of environmental sequences using MEGAN4. Genome Res. 21, 1552–1560 (2011)

Longo, M. S., O’Neill, M. J. & O’Neill, R. J. Abundant human DNA contamination identified in non-primate genome databases. PLoS One 6, e16410 (2011)

Schubert, M. et al. Improving ancient DNA read mapping against modern reference genomes. BMC Genomics 13, 178 (2012)

Ginolhac, A., Rasmussen, M., Gilbert, M. T., Willerslev, E. & Orlando, L. mapDamage: testing for damage patterns in ancient DNA sequences. Bioinformatics 27, 2153–2155 (2011)

Darling, A. E., Mau, B. & Perna, N. T. progressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS One 5, e11147 (2010)

Stamatakis, A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22, 2688–2690 (2006)

Acknowledgements

We thank G. Manzi, the Odontological Collection of the Royal College of Surgeons, Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, and Adelaide University for access to dental calculus material. We thank A. Croxford for DNA sequencing and A. Walker, J. Krause and A. Herbig for feedback. The Australian Research Council supported this work through the Discovery Project and Fellowship schemes. We acknowledge the fundamental contribution of D. Brothwell (1933-2016) to this research by initiating the archaeological study of dental calculus.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.S.W., K.D. and A.C. designed the study; A.G.M., K.W.A., D.C., V.D., M.Fa., M.Fr., N.G., W.H., K.Hard., K.Harv., P.H., J.K., C.L.F., M.d.l.R., A.R., P.S., A.S., D.U. and J.W. provided samples and interpretations of associated archaeological goods; L.S.W. performed experiments; L.S.W., S.D., E.C.H., J.S., B.L., J.B., L.A., A.G.F. and A.C. performed bioinformatics analysis and interpretation of the data; D.H.H. developed bioinformatics tools; N.G., J.K., and G.T. analysed medical relevance of data; L.S.W. and A.C. wrote the paper; and all authors contributed to editing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Reviewer Information Nature thanks P. Ungar and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Figure 1 Proportions of bacterial phyla from filtered and unfiltered 16S amplicon and shotgun sequencing datasets.

a, b, Proportions of bacterial phyla of El Sidrón 1(a) and the modern human oral microbiota were compared (b). Samples in blue are from shotgun sequencing datasets, whereas samples in red are from 16S amplicon datasets. The different shapes of each data point correspond to the microbial phyla, which are displayed next to each phyla grouping (for example, the cross represents Proteobacteria for both 16S and shotgun sequencing datasets).

Extended Data Figure 2 The presence/absence distance (Jaccard) calculated for each 16S OTU observed in the 99th percentile. OTUs from each sample were then clustered according to dissimilarity within each sample.

Clusters of unique operational taxonomic units (OTUs) are identified (dashed lines) and labelled according to cluster relationships (red, no-agriculture; green, agriculture; purple, 19th century; fuchsia, modern time). Calculations are consistent with ancient DNA metagenomic analysis.

Extended Data Figure 3 SourceTracker take-one-out analysis for all samples.

a, b, Samples were grouped into time periods, and the proportion of each taxa originating from each sample group was inferred. Other, summed proportions across non-oral microbial groups (non-oral human microbiome, air, and soil) and unknown classification. Groups have a minimum of two samples (the non-human primate group is removed in filtered analysis as filtering reduced the sample number to one) and are displayed for the raw (unfiltered) OTU (a) (n = 54) and filtered OTU (b) data (n = 42).

Extended Data Figure 4 MALTX analysis compared to 16S and alternative shotgun analysis methods.

a, Unfiltered prokaryotic phyla identified from 16S rRNA (QIIME) and shotgun sequencing results (MALTX) are compared. b, Raw shotgun sequences were analysed by MALTX and by MG-RAST, and bacterial phyla and kingdom level results are displayed.

Extended Data Figure 5 MALTX benchmarked using modern oral microbiota and simulated datasets.

a, Phyla identified in simulated metagenomes (modern or ancient) are shown for four different analysis programs: MALTX, DIAMOND, MetaPhylAn, and MG-RAST. b, Simulated metagenomes (modern (circle) or ancient (square; damaged)) analysed using four different software (DIAMOND (green), MALT (red), MetaPhylAn (blue), MG-RAST (orange)) were UPGMA-clustered according to Bray–Curtis distances calculated from genera within samples. c, Phyla identified by MALTX analysis in shotgun and amplicon oral datasets obtained from this study and MG-RAST are displayed in stacked bar plots.

Extended Data Figure 6 The composition of DNA sequences within ancient dental calculus in contrast to laboratory and environmental controls.

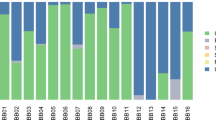

a, Sequences identified by MALTX at the phyla level are displayed for dental calculus samples, extraction blank controls (EBCs), and environmental samples. Ancient dental calculus samples are ordered according to age, with the oldest specimens listed on the left. b, Identified reads from MALTX were filtered to remove reads corresponding to species identified in extraction blank controls from QG DNA extractions and environmental controls. c, Filtered data was summarized to analyse only archaea and bacterial phyla typically found in the modern oral cavity. Dental calculus samples are displayed in order of age.

Extended Data Figure 7 MapDamage analysis of oral bacterial species shared between Neanderthals and the modern human.

a, b, The per cent of C–T mutations (a) and read length (b) calculated from mapped reads from each sample are shown for ten conserved species.

Extended Data Figure 8 Alpha diversity from deeply sequenced unfiltered shotgun datasets.

a, b, Calculations of rarefied data were carried out using Shannon–Weaver (a) and Simpson’s reciprocal (b) indexes.

Extended Data Figure 9 Neanderthal microbiota compared to other ancient and modern calculus specimens.

a, UPGMA clustering of Bray–Curtis values were calculated from filtered rarefied shotgun data. b, The groups in a split on the basis of their differences in proportion of Gram-positive and Gram-negative phyla in shotgun datasets and were plotted for each group (chimpanzee and modern human, n = 1; Neanderthals, n = 3). Error bars represent s.d.

Extended Data Figure 10 Phylogenetic analysis of unlikely bacterial pathogens observed in Neanderthal dental calculus.

a, Reads from El Sidrón 2 were mapped onto shared Neisseria genes (that is, those gene regions shared between all of the species) and the resulting DNA fragments were aligned in MUGSY, compared to RAxML, and bootstrapped with 100 iterations. b, Phylogenetic analysis of whooping cough in Neanderthals was completed. Shared genomic regions within publically available Bordetella genomes were compared to ancient Bordetella reads from El Sidrón Neanderthals using RAxML with 1,000 iterations (bootstrap values).

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Weyrich, L., Duchene, S., Soubrier, J. et al. Neanderthal behaviour, diet, and disease inferred from ancient DNA in dental calculus. Nature 544, 357–361 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21674

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21674

This article is cited by

-

Phylogeny and disease associations of a widespread and ancient intestinal bacteriophage lineage

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Oral microbial diversity in 18th century African individuals from South Carolina

Communications Biology (2024)

-

Late pleistocene exploitation of Ephedra in a funerary context in Morocco

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Metagenomic analysis of Mesolithic chewed pitch reveals poor oral health among stone age individuals

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Beyond reasonable doubt: reconsidering Neanderthal aesthetic capacity

Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences (2024)