Greek Pottery – History of Ceramics in Ancient Greece

Because of its remarkable longevity, ancient Greek pottery makes up a substantial portion of the archaeological legacy of ancient Greece, and because there is so much of it, it has had a correspondingly great impact on our knowledge of Greek civilization. The shards of ancient Greek vases abandoned or buried in the first millennium BC remain the finest resource available for understanding the traditional life and mentality of the Greeks. Several Greek vessels were created domestically for daily and culinary use, while better pottery from locations such as Attica was acquired by other civilizations around the Mediterranean, including the Etruscans of Italy. There were several regional variations, notably the South Italian ancient Greek pottery designs. To learn more, let’s get into our article on Greek pottery facts.

Ancient Greek Pottery

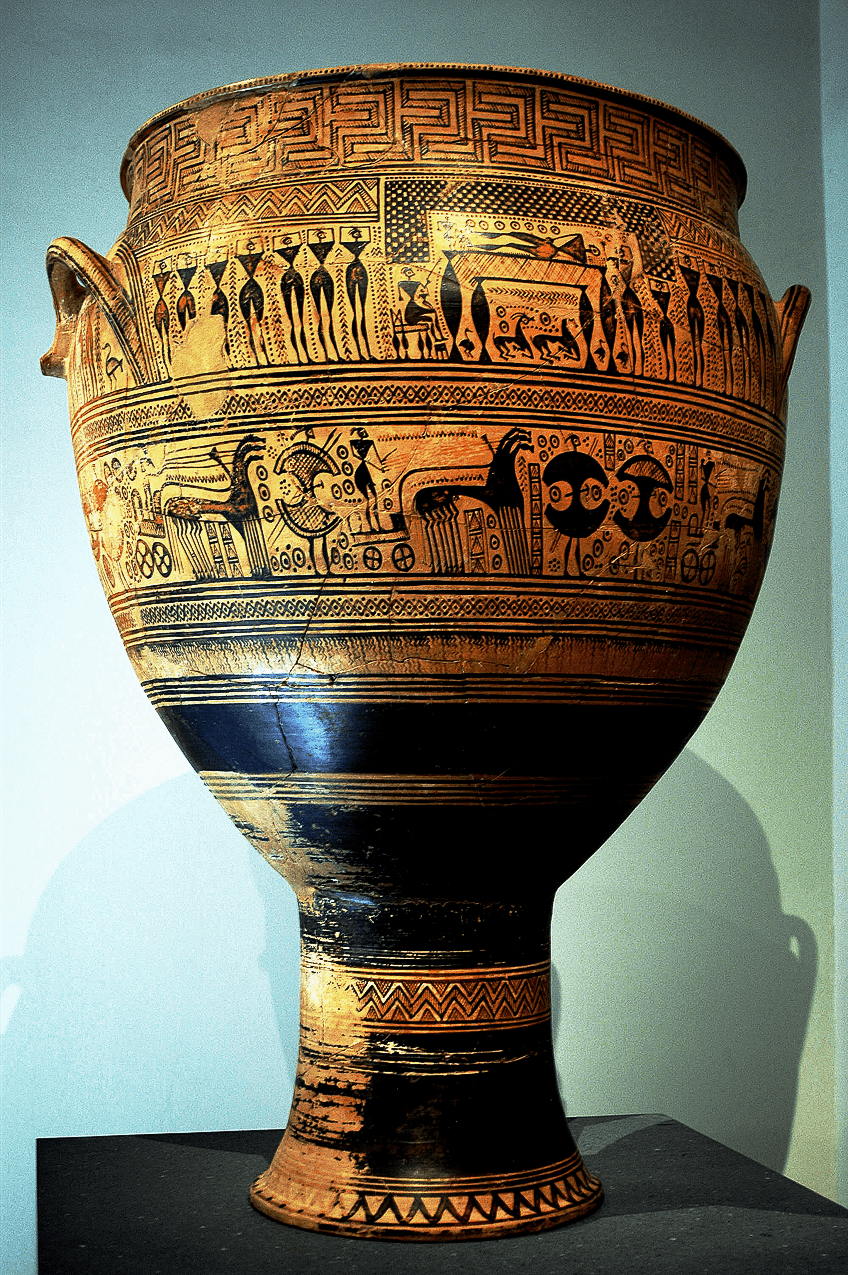

Various types and forms of ancient Greek vases were utilized at these locations. Some were employed as grave markers, some ancient Greek vases acted as tomb gifts, and others appear to have been regarded partially as objets d’art, as did later terracotta figures. Some were extremely ornate Greek vases designed for aristocratic consumption and home adornment as much as they served storage or other duty, such as the krater, which was traditionally used to dilute wine.

With the emergence of vase painting, there was an increase in embellishment in Greek pottery art.

Geometry-based artwork in Greek vase patterns appeared at the same time as the Orientalizing period in the late Dark Age era and the early Archaic period in Greece. Initially, black-figure ancient Greek pottery designs were manufactured in Archaic and Classical Greece, but other varieties such as red-figure vessels and the white ground technique evolved.

Styles such as West Slope Ware were typical of the later Hellenistic era, which witnessed the demise of vase painting.

Rediscovery

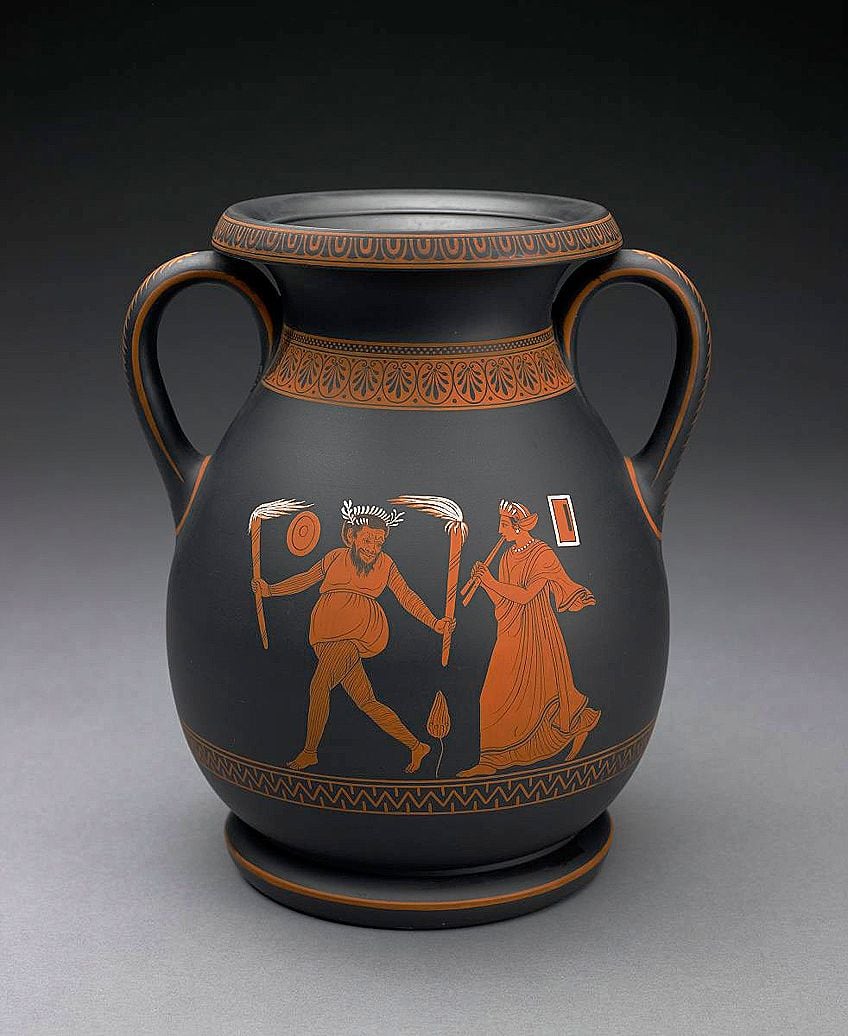

The rebirth of interest in Greek art began quite a while after the revival of classical study throughout the Renaissance, and it was renewed in the 1630s by the intellectuals around Nicolas Poussin in Rome. Despite the fact that tiny collections of vases unearthed from ancient graves in Italy were formed in the 15th and 16th centuries, they were considered Etruscan.

It is probable that Lorenzo de Medici purchased many Attic vases straight from Greece; nevertheless, the link between them and the ones discovered in central Italy was made considerably later.

Most of the initial research of Greek vessels took the form of making books of the pictures they depicted, however, neither D’Hancarville’s nor Tischbein’s folios record the forms or attempt to provide a date, making them untrustworthy as archaeological records. Real efforts at academic research made steady progress throughout the nineteenth century, beginning with the establishment in 1828 of the Instituto di Corrispondenza in Rome.

Finally, Otto Jahn established the norm for thorough study and analysis of Greek pottery art, meticulously noting the forms and inscriptions. For many years, Jahn’s work was the classic reference on the chronology and dating of Greek vessels, although, like Gerhard, he placed the advent of the red-figure method a hundred years later than was actually the case.

In 1885 The Archaeological Society of Athens explored the Acropolis and discovered “Persian rubbish” of red-figure jars destroyed by Persian conquerors around 480 BC. With a more solidly defined chronology, Adolf Furtwängler and his pupils were able to date the layers of his archaeological investigations by the character of the pottery found inside them in the 1880s and 90s, a technique of seriation Flinders Petrie would subsequently apply to undecorated Egyptian pottery.

Whereas the nineteenth century was a time of Greek discovery and the establishment of first principles, the twentieth century was a time of stability and academic industry. Efforts to document and publish the entirety of public vases began with Edmond Pottier’s construction of the “Corpus vasorum antiquorum” and John Beazley’s “Beazley Archive”.

Types and Uses

The names we give to Greek vase designs are generally based on custom rather than historical truth; some are marked with their original titles, while others are the product of early archaeologists’ unsuccessful attempts to match the physical item with a recognized name from Greek literature.

To better comprehend the link between form and function, ancient Greek pottery may be split into four major categories, each of which is represented here with examples of common types: storage vessels, mixing vessels, and greek vessels for oils and perfumes.

In addition to their practical uses, certain vase forms were linked with rituals, while others were associated with athletics and the arena. Although not all of their applications are known, academics make fair near approximations as to what purpose a component would have had when there is doubt. Some, for example, serve only a ceremonial purpose.

Some of the containers were made to serve as burial markers. Males were designated by craters, while females were marked by amphorae. This enabled them to live, and it is for this reason that some will show funeral processions. The oil used as burial gifts was found in white ground lekythoi, which appear to have been produced specifically for that purpose.

Since the 8th century BC, there has been a global market for ancient Greek vases, which Corinth and Athens controlled until the end of the 4th century BC. The breadth of this commerce may be estimated by charting the location maps of these vessels outside of Greece, although this does not allow for presents or immigration.

The number of Panathenaic discovered in Etruscan graves could only be attributed to the presence of a second-hand market. As Athens’ political influence diminished throughout the Hellenistic period, South Italian products started to control the Western Mediterranean export market.

Greek Vase Patterns and Painting

The most well-known characteristic of ancient Greek pottery is finely decorated vases. These were not the typical types of pottery used by most people, but they were inexpensive enough to be affordable to a wide variety of individuals.

Because few instances of ancient Greek artwork have survived, modern historians must uncover the advancement of ancient Greek art through ancient Greek vases designs, which endures in huge volumes and is also the best reference we have to the conventional soul and actions of the ancient Greeks, along with Ancient Greek literature.

Development of Greek Pottery Art

Ancient Greek pottery designs, such as those unearthed at Dimini and Sesklo, dates back to the Stone Age. More intricate painting on Greek pottery dates back to the Bronze Age’s Minoan and Mycenaean pottery, some of which display the ambitious figurative art that would become highly advanced and characteristic.

After several years dominated by geometric decorating styles that became increasingly intricate, figurative features resurfaced in the 8th century. From the late seventh century until around 300 BC, emerging forms of figure-led paintings were at their pinnacle in terms of output and quality, and they were extensively exported.

Throughout the Greek Dark Age, which lasted from the 11th to the 8th century BC, the dominating early form was protogeometric art, which mostly used circular and wavy ornamental motifs. This was followed in mainland Greece, Anatolia, the Aegean, and Italy by the geometric art pottery style, which used clean rows of geometric forms.

Starting in the 8th century BC and enduring until the late 5th century BC, the era of Archaic Greece had seen the emergence of the Orientalizing era, led primarily by ancient Corinth, in which the prior stick-figures of geometric pottery became hashed out amid patterns that supplanted the geometric shapes.

The Attic vase painting dominates the traditional ceramic décor. Vase production was essentially the domain of Athens – it is clearly recorded that artists and potters at Corinth, Boeotia, Argos, Crete, and the Cyclades were content to follow the Attic style.

The varieties of red-figure pottery, black-figure pottery, and the white ground technique were well developed by the end of the Archaic period and would go on to be employed during the Classical Greek era, which spanned from the early 5th through to the late 4th centuries BC.

Protogeometric Styles

Vases from the protogeometric era indicate the revival of craft production following the demise of the Mycenaean Palace civilization and the subsequent Greek dark ages. It is one of the few ways of artistic expression in this period, other than jewelry, because the sculpture, massive building, and fresco painting of this period are unknown to us.

By 1050 BC, life on the Greek peninsula appears to have settled down enough to allow for a significant advance in the manufacturing of pottery.

The style is limited to the portrayal of spheres, triangles, wavy lines, and arcs, but they are positioned with apparent care and precision, most likely helped by a compass and many brushes. The location of Lefkandi, where a cache of burial goods was discovered, is one of our most major sources of pottery from this period.

This demonstrates a characteristic Euboian protogeometric style that persisted into the early 8th century.

Geometric Style

In the 9th and 8th centuries BC, geometric art thrived. It was distinguished by new motifs that broke with the portrayal of the Minoan and Mycenaean periods: meanders, triangles, and other geometrical embellishments, as opposed to the preceding style’s largely circular forms. Nevertheless, our chronology for this new art style is based on exported products discovered in datable contexts elsewhere.

Only abstract themes are seen in the early geometrical style, which is classified as the “Black Dipylon” aesthetic, which is distinguished by the heavy use of black varnish. With the Middle Geometrical, figurative decoration appears: they are originally identical groups of animals such as horses, deers, heifers, geese, and so on, which differ with the geometrical bands. Parallel to this, the decorating grows more elaborate and ornate; the painter is hesitant to leave empty areas and fills them with swirls.

This is known as fear of emptiness and will last till the conclusion of the geometrical era. Human figures began to appear in the mid-century, with the best-known examples being those found on vases at Dipylon, one of Athens’ cemeteries. The remains of these huge burial jars depict mostly processions of chariots or soldiers or funerary scenes.

Except for the legs, which are fairly protuberant, the bodies are portrayed geometrically. In the instance of soldiers, a plate in the shape of a diabolo covers the middle section of the body. The limbs and necks of the horses, as well as the rims of the chariots, are depicted side by side, without viewpoint.

The hand of this artist, known as the Dipylon Master in the lack of a signature, could be recognized on various items, particularly colossal amphorae.

At the conclusion of the period, depictions of mythology occur, most likely when Homer formalizes the Trojan cycle legends in the Iliad and Odyssey. The interpretations here, however, pose a danger to the contemporary observer: a clash between two warriors might be a Homeric duel or plain battle; a failed boat can symbolize Odysseus’ disaster or any sad sailor.

Finally, there are local schools in Greece. Greek Pottery production was essentially the domain of Athens — it is clearly recorded that, as in the proto-geometrical era, artists and potters at Boeotia, Corinth, Argos, Crete, and the Cyclades were content to imitate the Attic style.

They developed their separate styles about the 8th century BC, with Argos excelling in realistic subjects and Crete adhering to a more rigid abstraction.

Orientalizing style

The Orientalizing style arose as a result of cultural turbulence in the 8th and 7th centuries BC in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Aegean. The East’s artifacts influenced a strongly stylistic yet recognizable representational aesthetic, which was encouraged by trade links with Asia Minor’s city-states.

Ivories, pottery, and metalwork from the Neo-Hittite states of Phoenicia and northern Syria, as well as commodities from Phrygia and Anatolian Urartu, found their way to Greece, but there was little interaction with the cultural capitals of Assyria or Egypt.

The new idiom emerged first in Corinth and then in Athens. It was distinguished by a wider vocabulary of motifs, including sphinxes, griffins, and lions, as well as a repertory of non-mythological animals grouped in friezes across the vase’s belly.

Painters began to include lotuses or palmettes into these friezes. Humans were depicted only infrequently. Those discovered are silhouette figures with some incised detail, maybe the forerunners of the incised silhouette figures of the black-figure era. There is enough detail on these figurines for experts to identify a variety of distinct painters’ hands. Geometrical aspects persisted in the proto-Corinthian style, which accepted these Orientalizing efforts while coexisting with a conservative sub-geometric style.

Corinthian pottery was sold across Greece, and its technique reached Athens, stimulating the creation of a less obviously Eastern idiom there. During this period, known as Proto-Attic, Orientalizing elements develop, but the characteristics remain unreal. The artists exhibit a fondness for traditional Geometrical Period subjects, like chariot processions. They do, however, use the line drawing method to substitute the silhouette.

The black and white style comes in the middle of the 7th century BC, with black figures on a white zone, supplemented by polychromy to portray the color of the flesh or clothes. Because the clay used at Athens was considerably more orange than that used in Corinth, it did not adapt itself as well to the portrayal of flesh. The Analatos Painter and the Polyphemos Painter are two Attican Orientalizing Painters. Crete, and particularly the Cyclades islands, are noted for their fondness for “plastic” vases, i.e., those with a paunch or collar shaped in the shape of an animal or a man’s head.

The griffin’s head is the most popular type of plastic vase on Aegina. The Paros-made Melanesian amphoras show scant understanding of Corinthian advances. They have a strong preference for epic compositions and horror vacui, as seen by a profusion of swastikas and swirls. Lastly, the Wild Goat Style, which was traditionally assigned to Rhodes as a result of an important find within the Kameiros necropolis, may be identified.

In reality, it is found across Asia Minor, with manufacturing concentrations in Miletus and Chios.

There are two types of oenochoes: those that imitate bronze figures and dishes with or without feet. The décor is structured in stacked layers in which stylized creatures, most often wild goats (thus the name), chase each other in friezes. The vacant areas are filled with a variety of ornamental designs.

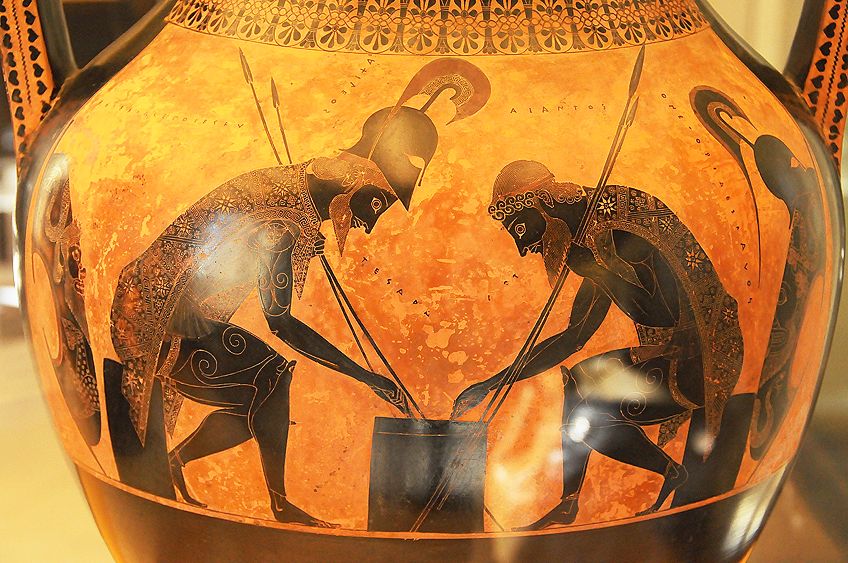

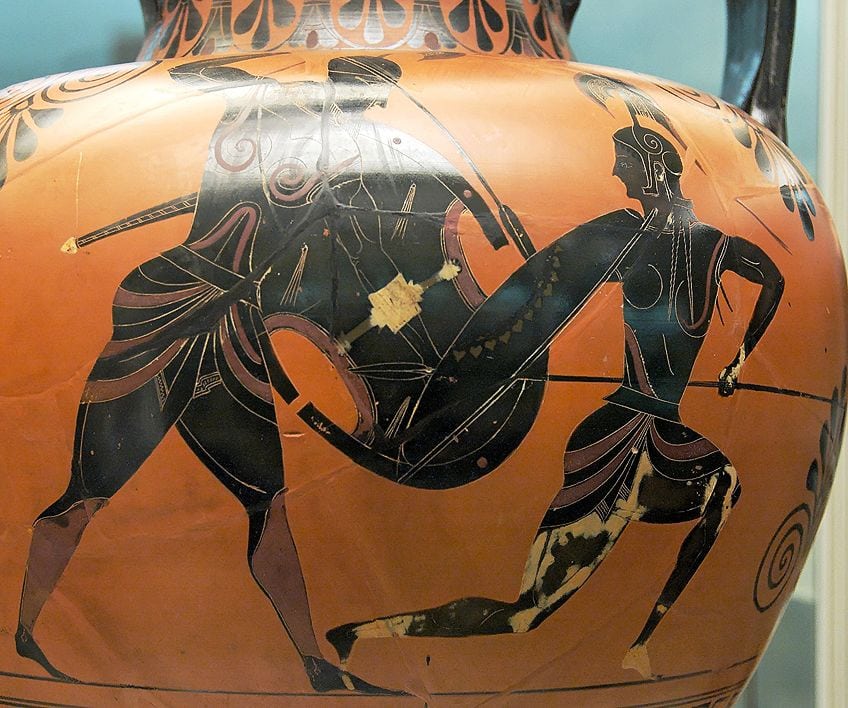

Black-Figure Technique

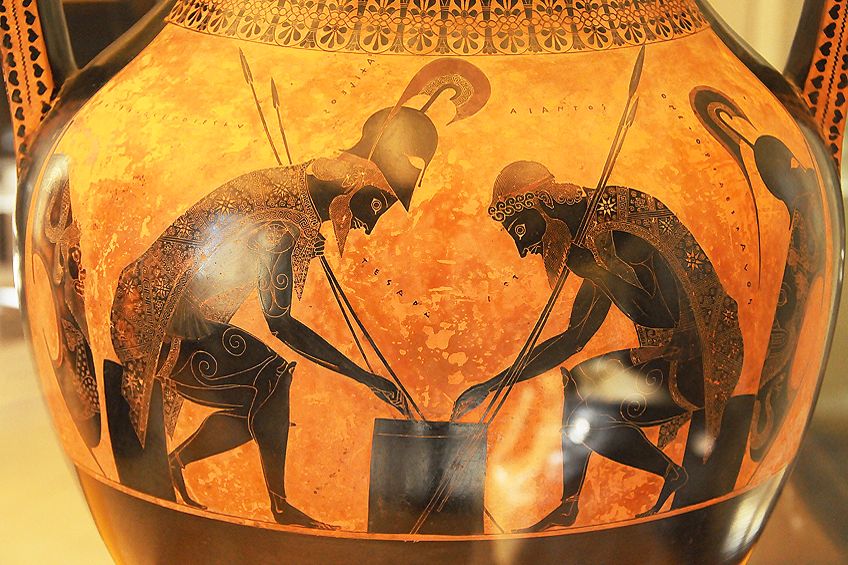

When one thinks about ancient Greek pottery designs, the most prominent image that comes to mind is a black figure. For long years, it was a prominent design in ancient Greece. The black-figure phase roughly corresponds to Winckelmann’s designation of the middle to late Archaic period, which lasted from 620 to 480 BC.

The method of incising silhouetted figures with energizing detail, commonly known as the black-figure method, was invented in the 7th century by the Corinthian city-states and expanded from there to other city-states and places such as Boeotia, Sparta, Euboea, Athens, and the east Greek islands.

The Corinthian fabric, which Darrell Amyx and Humfry Payne have thoroughly researched, may be identified through the analogous presentation of human and animal forms. The animal patterns dominate the vase and demonstrate the most innovation in the early era of the Corinthian black figures.

During the middle to the late period, as Corinthian painters developed confidence in their representation of the human form, the scale of the animal frieze decreased in relation to the human scenario. By the mid-6th century BC, the grade of Corinthian ware had deteriorated to the point that some Corinthian artists would conceal their pots with a crimson slip to imitate superior Athenian ware.

Researchers in Athens discovered the first known examples of vase painters marking their works, one being dinos by Sophilos, which may be indicative of their rising ambition as artists in making the colossal work necessary as burial markers, such as Kleitias’ François Vase. Many academics believe Exekias and the Amasis Painter to have produced the best work in the style, owing to their sense of composition and storytelling.

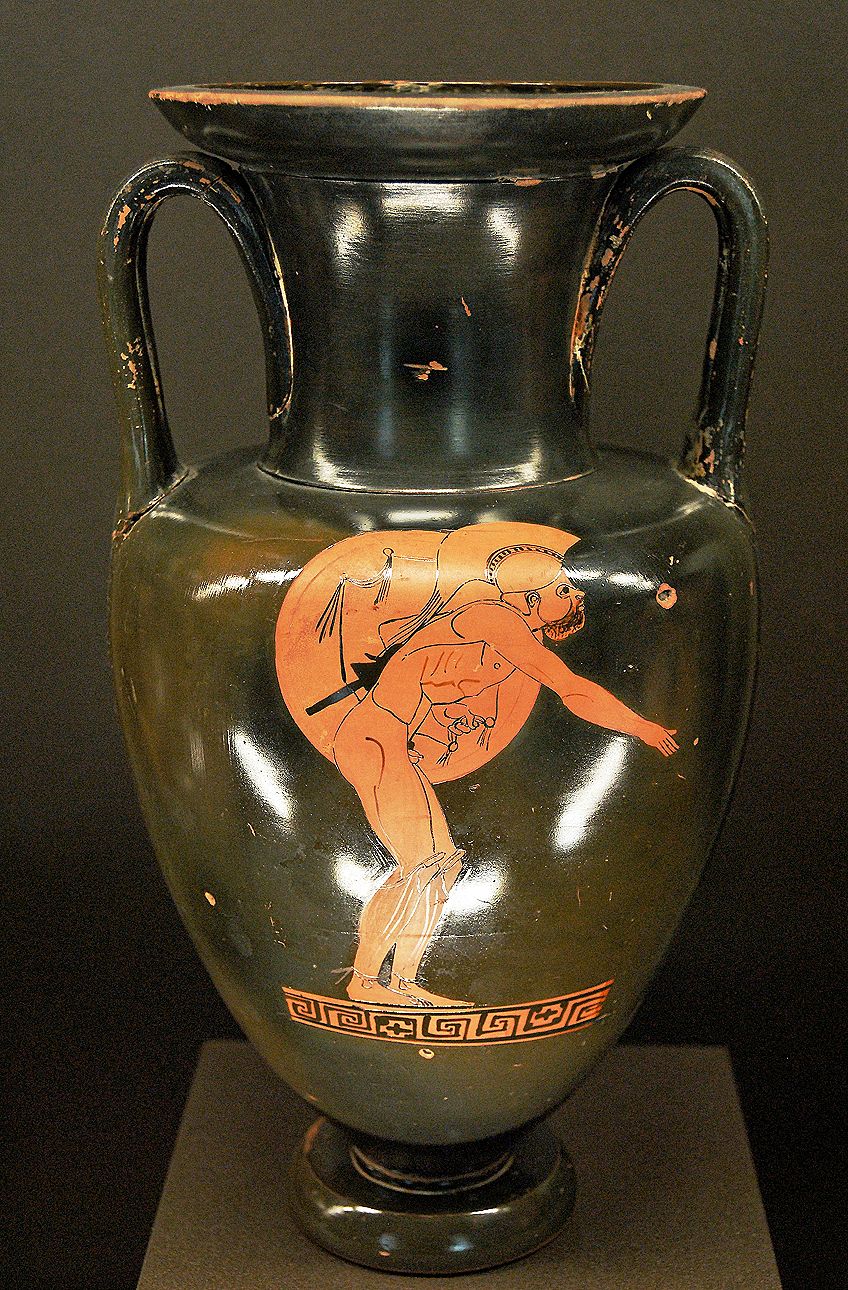

Around 520 BC, the Andokides Painter, Oltos, and Psiax devised the red-figure method, which was progressively adopted in the style of the bilingual vase. Red-figure rapidly surpassed black-figure, while black-figure was still used in the Panathanaic Amphora far into the 4th century BC.

Red-Figure Technique

The red-figure method was invented by the Athenians in the late sixth century. It was the polar opposite of a black figure with a red backdrop. The capacity to create detail by straight painting rather than by incision provided painters with additional expressive options such as three-quarter profiles, more anatomical detail, and perspective representation.

The first generation of red-figure artists used both red- and black-figure techniques, as well as other approaches such as Six’s technique and white-ground, which was created concurrently with red-figure. The Pioneers’ similar principles and ambitions, such as those of Euphronios and Euthymides, indicate that they were something resembling a self-conscious movement, yet they left no legacy other than their own work.

According to John Boardman, the research on their work “may be viewed as an archaeological victory” since “the rebuilding of their careers, common goal, and even rivalry can be taken as an archaeological success.” The following school of late Archaic vase artists introduced more naturalism into the style, as seen by the progressive alteration of the profile eye.

A variety of distinct schools of red-figure paintings had emerged by the early to the high classical era.

The Mannerists affiliated with Myson’s studio and illustrated by the Pan Painter adhere to archaic elements such as stiff draperies and awkward stances, which they mix with exaggerated motions. The Berlin Painter’s school, in the shape of the Achilles Painter and his friends (who might be the Berlin Painter’s students), on the other hand, preferred a naturalistic attitude, frequently of a single person against a solid black backdrop or controlled white-ground lekythoi.

That completes our article on Greek pottery facts. Because of its exceptional endurance, ancient Greek pottery constitutes a significant element of Greece’s archaeological record, and because there is so much of it, it has had a proportionally large influence on our understanding of Greek civilization. The shards of ancient Greek vases abandoned or buried in the first millennium BC remain the most valuable resource for comprehending the Greeks’ conventional life and thought. Several Greek pots were made at home for everyday and culinary use, while superior pottery from places like Attica was purchased by other civilizations across the Mediterranean, especially the Etruscans of Italy. There were various regional variants, most notably the ancient Greek ceramic styles from South Italy.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Materials Were Used to Produce Greek Vases Designs?

The clay used to make pottery was widely accessible across Greece, but the finest was Attic clay, which had a high iron concentration and produced an orange-red color with a faint shine when burned, as well as the pale buff of Corinth. Clay was commonly processed and refined in settling tanks to produce varying material consistencies dependent on the container types to be built with it. Ancient Greek pottery was generally created on the potter’s wheel and was typically created in distinct horizontal portions.

How Was the Greek Vase Pattern Made?

This approach varied depending on the ornamental style prevalent at the time, but common ways included painting the entire or sections of the vase with a thin black sticky paint applied with a brush, the markings of which are still apparent in many cases. This black paint was made from a combination of alkali potash or soda, silicon-containing clay, and black ferrous oxide of iron. The paint was applied to the pot using a fixative made of urine or vinegar, which burnt away in the kiln’s heat, cementing the pigment to the clay.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Greek Pottery – History of Ceramics in Ancient Greece.” Art in Context. March 11, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/greek-pottery/

Meyer, I. (2022, 11 March). Greek Pottery – History of Ceramics in Ancient Greece. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/greek-pottery/

Meyer, Isabella. “Greek Pottery – History of Ceramics in Ancient Greece.” Art in Context, March 11, 2022. https://artincontext.org/greek-pottery/.