Katsushika Hokusai – The Life and Works of This Famous Japanese Artist

Katsushika Hokusai is often credited as the most famous Japanese artist in the world. His prints were sought after throughout his life until this very day. Without Hokusai’s daring imagination and dedicated work ethic, we may never have received some of the greatest masterpieces of modern art.

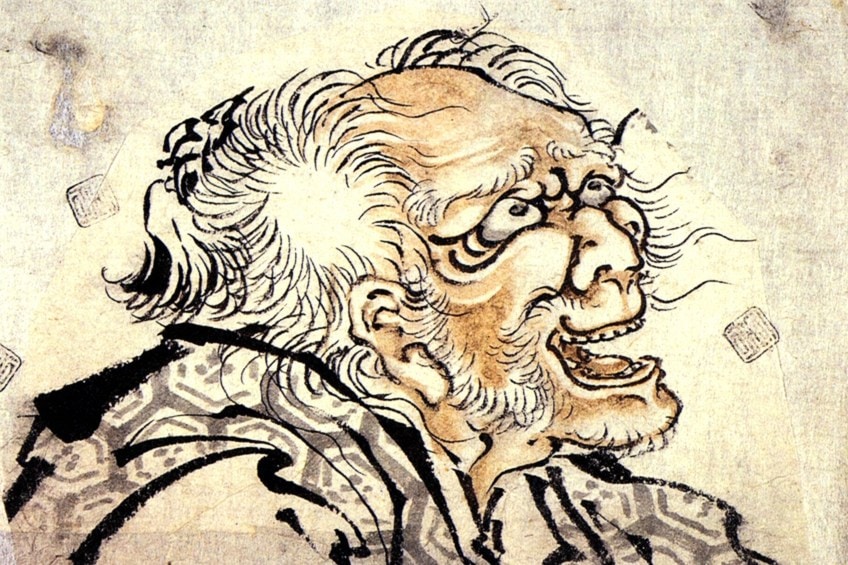

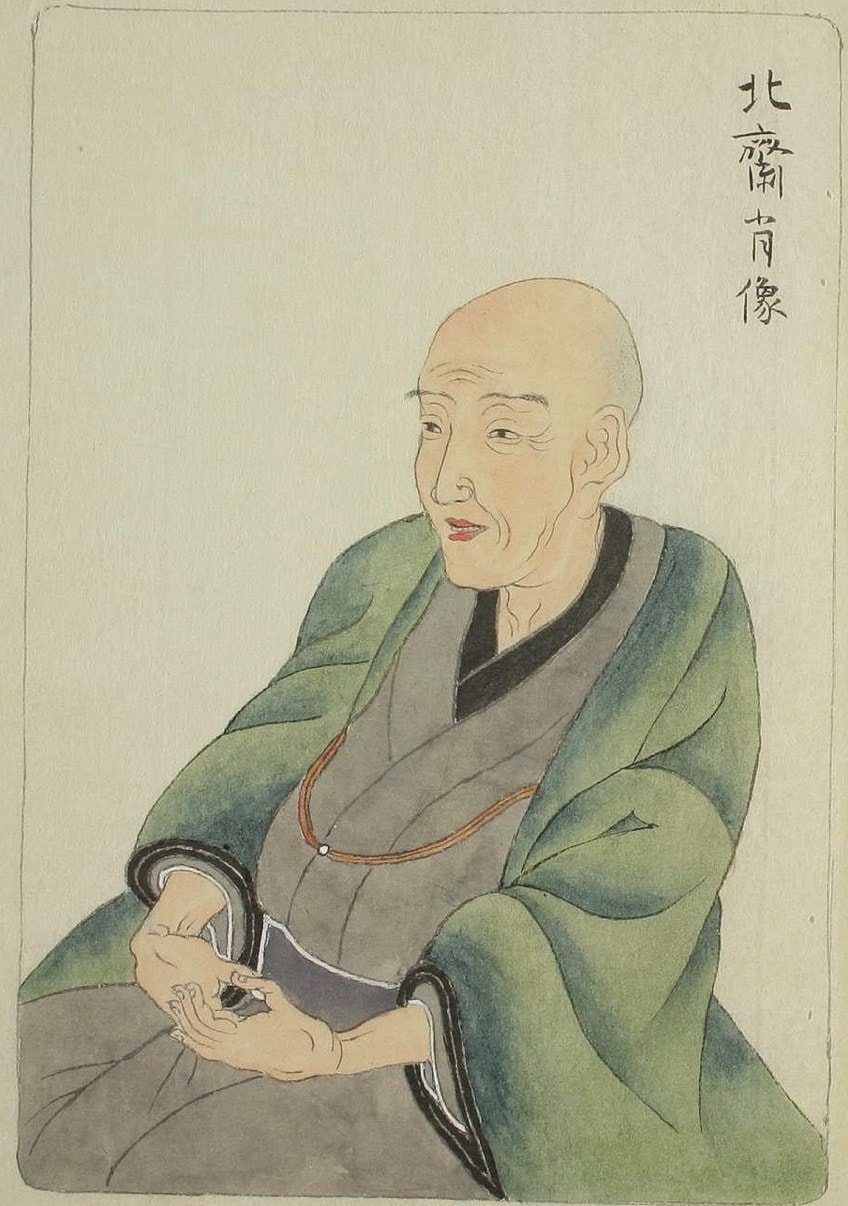

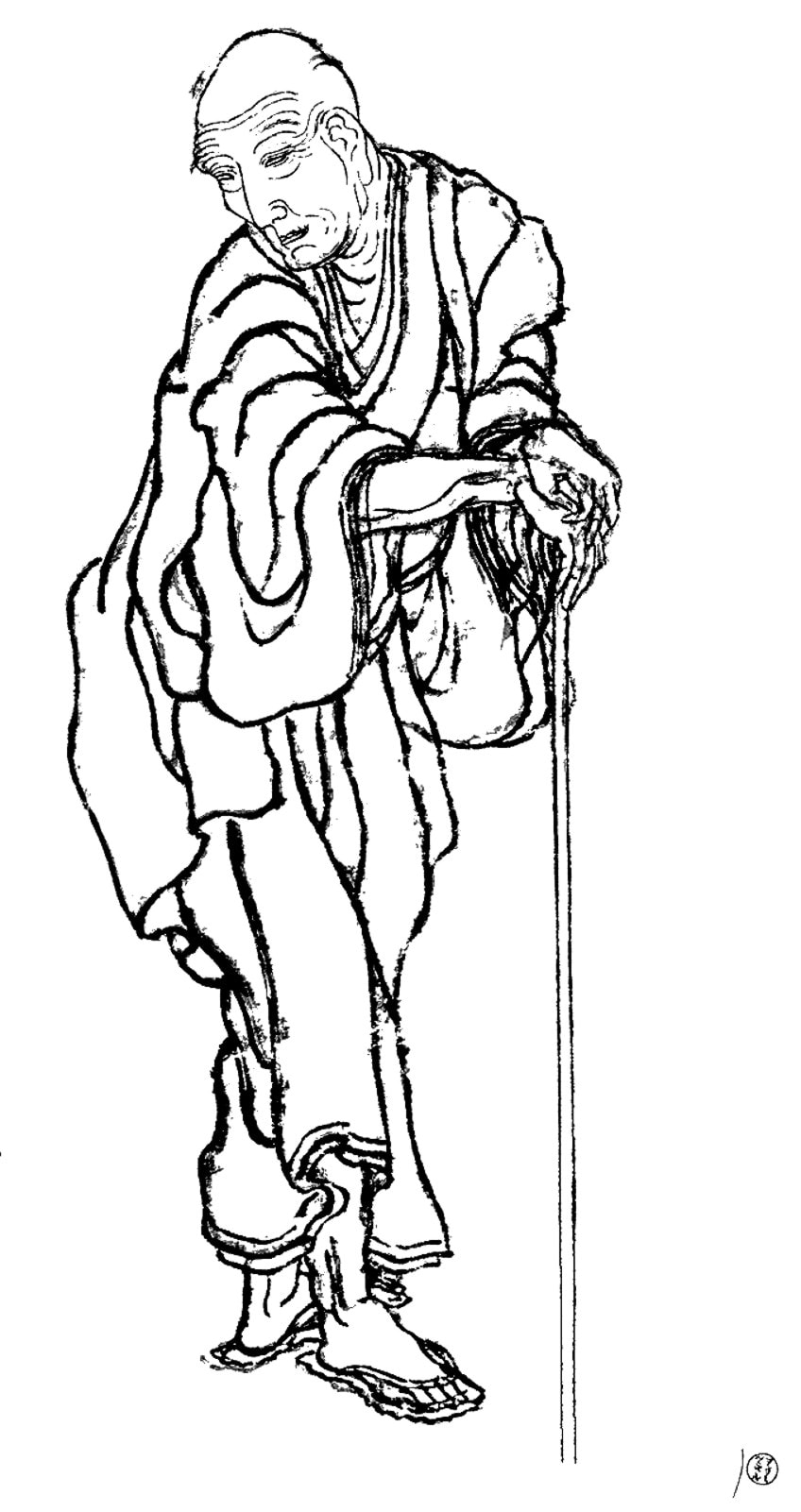

Old Master Hokusai

Katsushika Hokusai’s woodblock print The Great Wave of Kanagawa (1830) hugely impacted both pop culture and art history. His artistic endeavors included book illustration and painting. In the times of the infamous Edo Period, Hokusai produced an estimated 30 000 artworks. His ukiyo-e prints delivered a depiction of the world which was a boldly abstracted blend of Western and Japanese art.

| Date of Birth | 31 October 1760 |

| Date of Death | 10 May 1849 |

| Place of Birth | Edo, Japan |

| Associated Art Movements | Edo period, Ukiyo-e |

| Genre / Style | Drawing, Painting, Printmaking Woodcut |

| Mediums Used | Woodcut |

| Dominant Themes | City scenes, Nature, mythology, folklore, working people, erotica |

A Katsushika Hokusai Biography

Katsushika Hokusai whose childhood name was Tokitarō was born in 1760 nearly 300 years ago. In the middle of the 18th century, Japan’s then capital Edo, which is now called Tokyo, was in the throes of the Edo Period. He lived most of his life in a central part of town on the east bank of the Simiyula River. His birth family had lived in the working-class districts of Edo but he was adopted by his uncle Nakajima Ise who was the official mirror-maker to the shōgun.

At the time, the adoption of male children was a common strategy for strengthening one’s lineage and social standing.

His close proximity to the royal court afforded Hokusai an excellent education and he was well placed for a career in the arts. As a child, he developed an interest in drawing. By the age of six, he was already using watercolor.

Hokusai learned to paint decorative mirror frames with the expectation that he would eventually join the family business. As a teenager, he became an apprentice to an engraver at which point he decided he wanted to be an artist. But his artistic endeavors continued to reflect his interest in mirrors, microscopes, and telescopes.

Hokusai was raised as a Buddhist, which made divinity incredibly important to him. Later in life, he christened himself Hokusai in honor of the goddess Myoken which means North Star. The sole stationary light in the heavens which the artist saw as a source for spiritual strength. One of his early works was an offering for Myoken’s temple.

Despite his successful professional life, Hokusai’s midlife brought on a long series of unfortunate events.

His first wife, with whom he had three children, died in the 1790s. Lightning literally struck him when he was 50. Then he suffered a minor stroke which meant he had to relearn his artistic skill. He remarried and had three more children but in 1828 his second wife also died. Two of his children also predeceased him. Then was forced to use his life savings to pay off his grandson’s gambling debts.

Eventually, Hokusai lost his home and had to move into a temple. He lived there for many years with his daughter who was also an artist. But in 1839, their lodgings were burned in a neighborhood fire. Hokusai and his daughter escaped the house through a window with only their paintbrushes. Thousands of his works are said to have been lost in the fire.

Fortunately, Hokusai was famous in his lifetime and the affordability of the print meant most people could afford to buy his work. This helped facilitate Hokusai’s survival through continuous bouts of poverty and hardship.

He changed his name many times throughout his lifetime. Japanese artists were known for changing their names when their style shifted or when they switched their social position.

Ukiyo-e (1615 – 1905)

The Edo Period, also known as the Tokugawa Period, began in 1603 when a high-ranking Shogun called Tokugawa founded a dynasty that would last over 200 years. The Tokugawa Shogun kept a tight grip on Japan. In 1639, the Shogun closed Japan’s borders, isolating the country from the outside world. Foreigners were expelled, Christianity was banned and immigration or emigration was punishable by death. Only limited trade was allowed with China and the Dutch, who had not been so aggressive with Christianity.

Until its collapse in the 1860s, the Edo Period was prosperous for Japan. Many industries flourished and, in these conditions, a quintessentially Japanese art was formed. Around 1680, book publishers began making single-sheet graphic prints which came to be known as Ukiyo-e.

The term Ukiyo-e means “pictures of the floating world”, including paintings, books, and prints. It is a pun on a Buddhist term meaning “sorrowful world”.

There were many different styles of painting in the Edo period of which the Floating World was one. The images of the “Floating World” were inspired by the everyday life of the celebrities and citizens of Edo in the 17th and 18th centuries.

This was a time when downtown Edo served as a court for the Shogun, attracting nobles and samurais from all over Japan. The subjects for these artists included the actors, sumo wrestlers, geisha, courtesans, and erotic scenes, filling the kabuki theaters and brothel districts on the northern outskirts of the city of Edo.

The increased trade created an environment of debauchery that must have seemed somewhat ephemeral, hence the term “Floating World”.

The thin veil of modesty provided by the term courtesan in the Western context implies a level of immorality. But in the Edo Period, there was nothing shameful about sex work. It was legal and extremely popular. As Ukiyo-e developed in the Red Light district of Edo, it boasted a healthy mix of explicit and non-explicit prints.

The collectible woodblock prints became a sensation much like modern-day trading cards. There was a steady demand for new prints to collect. Although printed by hand, mass production made them highly profitable for publishers. Because of the mass production, they were considered low in social prestige whereas traditional painting remained prestigious.

Still, Ukiyo-e made art relatable and accessible to all classes as these prints could be bought for the price of a bowl of noodles.

The Ukiyo-e aesthetic differed in several ways from Western art. The first was perspective. The vibrant colors of Ukiyo-e were contrasted by the bottomless range of grays and browns that had typified Western art at the time. The Edo Period also stood out for its unique use of shapes and forms. Artists had not strived for realism but favored structured drawings that emphasized atmosphere and energy.

Early Career

By the time Hokusai is born in 1760, the movement had existed for more than a hundred years. However, he was born in a time of great change. In the mid-18th century, Edo had become the biggest city in the world with a population of one million. It had become a sophisticated consumer society.

Though they were once considered the lowest social class merchants, the city rose through the ranks as the economy boomed. They could afford now education, travel, books, and art.

At the age of 14, he apprenticed with a woodblock cutter, so he learned this important aspect of the production of Ukiyo-e. It began with a publisher who would commission an image from the artist who made a drawing on thin paper. Then the original drawing was reversed, glued to the block, and rubbed down with an instrument called a baren.

The carver then peeled off most of the paper while it was still damp from the moisture of the glue, leaving the lines of the original image on the surface of the woodblock. The brush line was then carved onto the wood. The original design was destroyed in the process, so the carvers had to possess immense skill and precision in order to mimic it.

In 1778, when Hokusai was 18-years-old, he began studying under the master printmaker Katsukawa Shunshō, who was influential to the Floating World school of popular art, producing thousands of color woodblock prints of the kabuki superstars of the day.

A year into his studies, Hokusai published the first series of his own Ukiyo-e prints depicting kabuki actors. These early prints match Katsukawa’s style. Early Hokusai art was made under the name Shunrō, which he was given by his master.

Hokusai’s mentor Shunshō died in 1793 and his successor Shunkō relieved Hokusai from his duties at the studio. This setback brought about a breakthrough in Hokusai’s artistic journey. Now that he was no longer busy designing repetitive pictures of courtesans and celebrities, he was able to expand his subject matter.

He turned his focus on nature and the daily lives of ordinary Japanese people.

Manga

Hokusai began using the name we know him by around 1800. Hokusai means “north studio”, a reference to the North Star, an important deity in Nichiren Buddhism. From 1804 until 1815, he illustrated the popular novels of Takizawa Bakin.

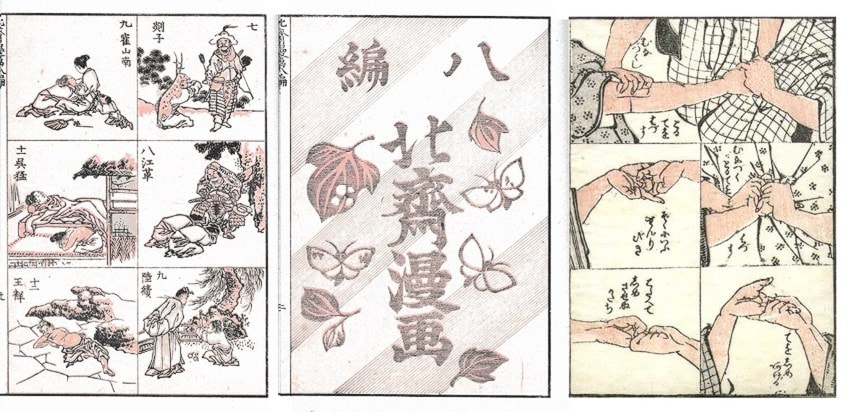

His success multiplied in 1811 when he began traveling and making random drawings of his observations. While visiting a friend and colleague in Megoria, a publisher saw his drawings and suggested that he compile them and publish a book.

The book title Hokusai Manga came from Hokusai himself, though his meaning is quite different from the popular comic books of today. “Manga” in Hokusai times meant random or informal drawings or sketches. While it has no storyline, Hokusai’s experience in novel illustration influenced his Manga.

The first in the Hokusai Manga series was Quick Lessons in Simplified Drawing (1812). The woodblock printed picture books included lots of models for people to copy as training. The images include landscapes, architecture, working people, animals, and fictional characters.

The book has an entire section of beautifully drawn and labeled images of various types of fish.

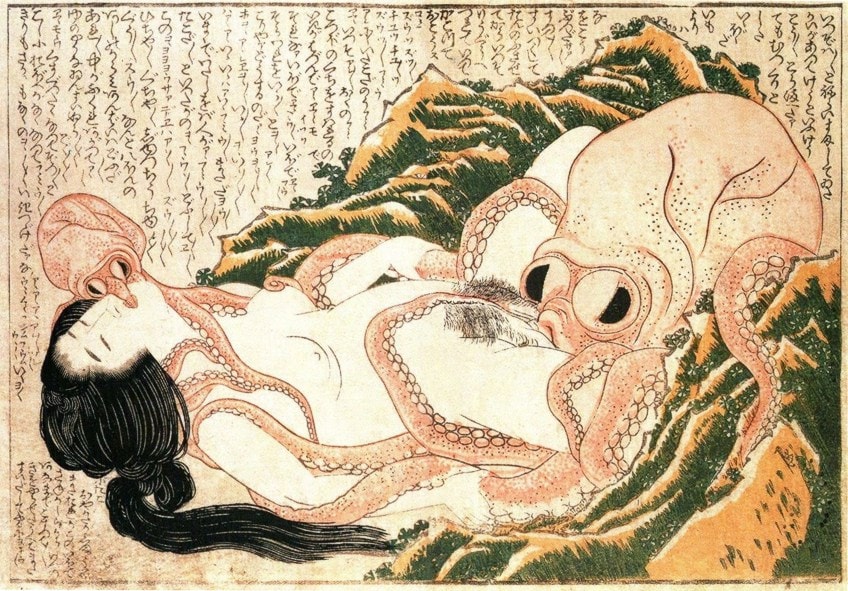

Around the same time, he also published Kinoe no Komatsu a widely popular book of erotic images. The famous Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife (1814) depicted a woman embroiled in sexual ecstasy with a couple of octopuses.

Having been published around the same time, these books were hugely popular and enormously influential. Hokusai’s Manga can be seen as a foundation for modern Manga. Hokusai published 12 volumes of Hokusai’s lost Manga in his lifetime, three more were published after his death.

Katsushika Hokusai’s Painting Style

Hokusai had worked with European perspective for some time, but the lessons he had picked up throughout his middle years began manifesting in his later years. In Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (c. 1829–1832), he combined a distinctly Japanese style with a distinctly Western style, taking his newfound techniques to their optimal resolution.

Perspective

Traditional painting styles like Yamato-e, which preceded Ukiyo-e, took the traditional Japanese perspective of the absent roofs. Classical Asian perspective depicted things higher up to show that they were at a distance. Western artists controlled the viewer’s point of view whereas Japanese landscape painters offered no marked point of access.

Time was also determined in Western art, but Japanese art had a more fluid sense of time, which included multiple dimensions.

Dutch merchants were allowed two trading ships per year. This was practically the only direct connection between Edo and Europe. Provided they had no trace of Christianity, Western books and pictures were embraced in Edo.

The Japanese had been familiar with the vanishing point since the 1740s. Its arrival had not been exalted there as it had been in Renaissance Europe. Instead, the Japanese saw it as a novelty. They used the amusing optical illusion for stage sets and toys.

The lowbrow images of Ukiyo-e took to European perspective in the 1780s.

By the early 1800s, Hokusai had responded to the high demand for these perspective pictures with a number of small prints exploring Western perspectives. Hokusai art depicted Edo through a Dutch lens by simultaneously imitating shading, depth, and linear perspective characteristic of European art and violating it to incorporate the classical Asian system.

Prussian Blue

During the Edo Period, the Japanese were self-sufficient but they enjoyed exotic goods. A new pigment would have been very interesting to Japanese artists. In 1829 one such synthetic blue was invented in Germany. The Japanese called it Berlin blue but we know it as Prussian blue.

It was initially imported to Japan by Dutch traders but in the late 1820s, the Chinese began importing too, making it much more affordable. This made it possible to use Prussian blue in Ukiyo-e prints.

Compared to previous blues, Prussian blue had a greater tonal range but the pigment was especially popular because it did not fade as earlier blues did. Earlier Ukiyo-e prints rarely used blue because earlier blues faded sometimes within weeks.

The drastic change in color was the result of Ukiyo-e artists being able to explore for the first time, painting the sky, mountains, and water with an improved blue color.

The Dutch who were fully aware that Hokusai was an innovator, awarded him a big commission for a series of paintings showing typical scenes of Japanese in 1822 when he was already in his 60s. He executed these works through his hybrid Japanese European style and the newfound blue.

Hokusai Artworks

While landscape prints were still not as lucrative as the kubuki Ukiyo-e prints in the late 18th century, sales would increase as a result of an increase in domestic travel within Japan. The merchants, pilgrims, and pleasure seekers who visited Mount Fuji created a need for a new genre of souvenirs in the form of woodblock prints of Japanese mountains art. Hokusai artworks offered a new window into Japanese landscapes and people.

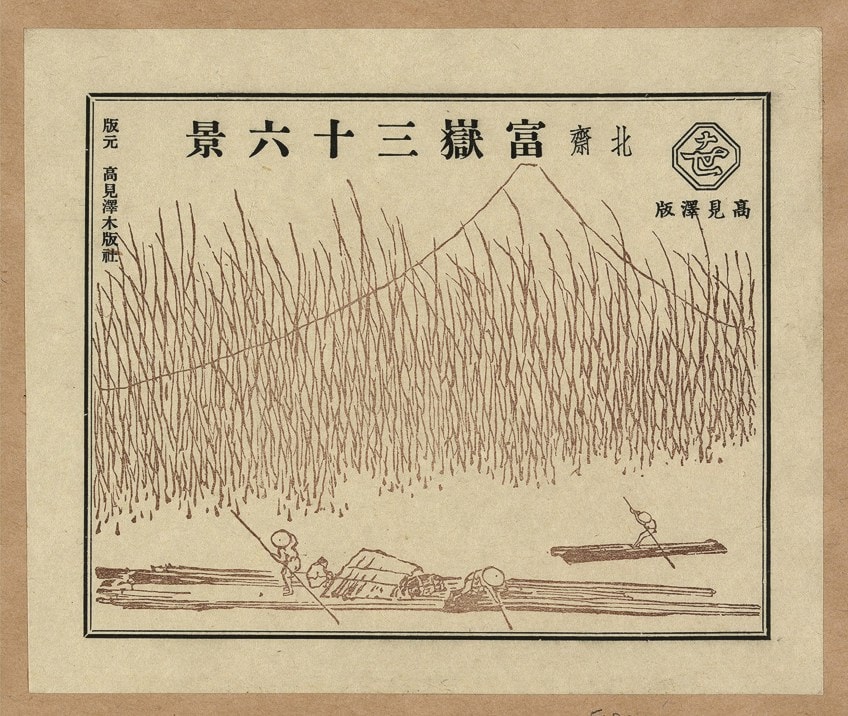

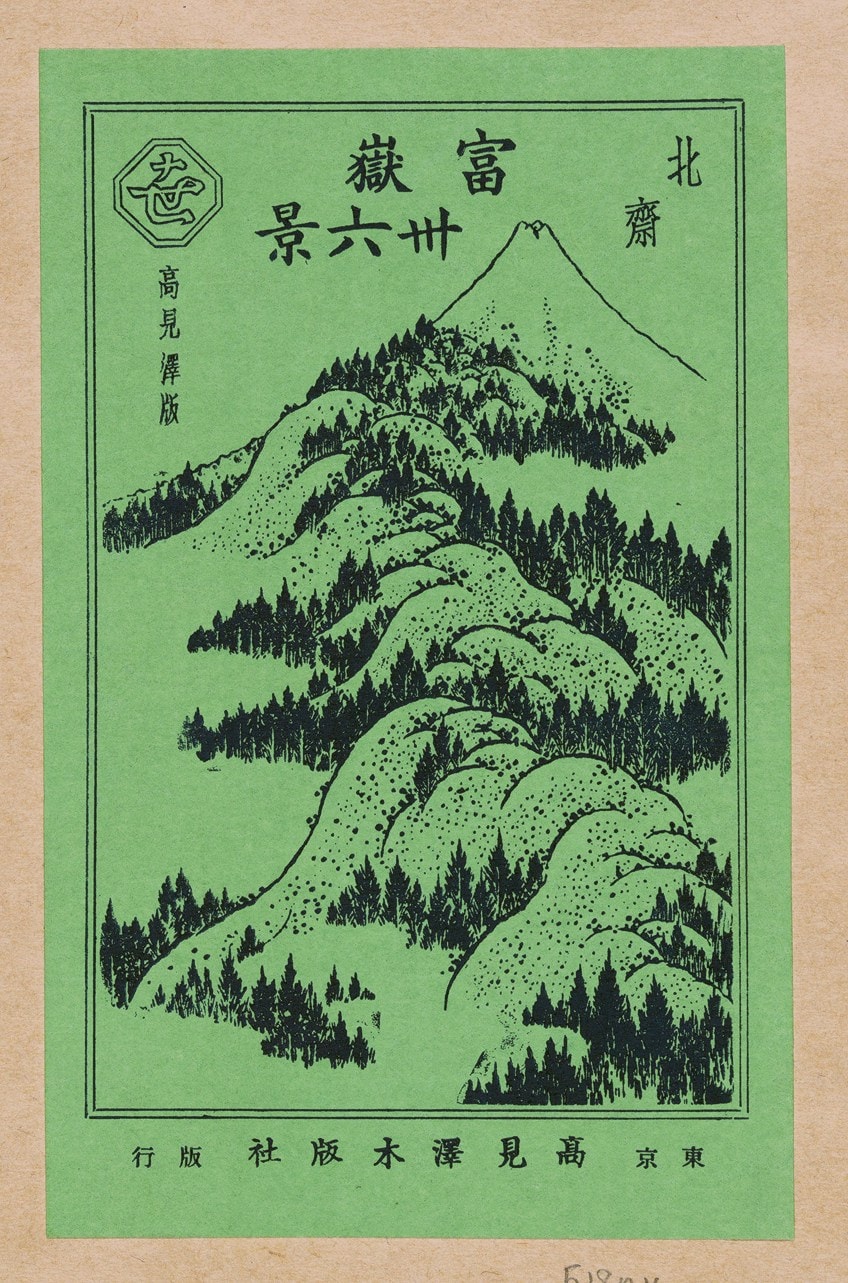

Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (c. 1829–1832)

Under his new pseudonym Iitsu, Hokusai was commissioned for Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (c. 1829–1832) initially to exploit the new color. The first five prints in the series were printed almost entirely in shades of Prussian blue, including a bit of indigo. Everything including the outlines which were usually printed in black was turned to blue.

Mount Fuji is the highest peak on the Japanese island though it is not a mountain, but an active volcano. It had long been considered a deity with over 800 shrines dedicated to it. It was also a site for religious pilgrimages. The belief was that the mountain was a source of immortality and a seat for the gods.

It represented stability and strength for Japan, which was still enmeshed in its own culture and made Japanese mountains art central.

In the idyllic series of block prints entitled Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, Hokusai indulges from almost every angle his obsession with this sacred landmark. Across 36 landscapes Mount Fuji shows up through the clouds, above the city, and on the horizon.

Hokusai would put everything he’d learned about style, color, and perspective over the past six decades into his “Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji”.

Hokusai was interested in the relationship between human activity and the mountain. He depicted people in the landscape, traveling, getting their hats blown off by the wind, or working the land. In one of the scenes, travelers are caught in a thunderstorm. A lightning flash at the back of the picture causes a strobe-light effect in the dark thunderous sky.

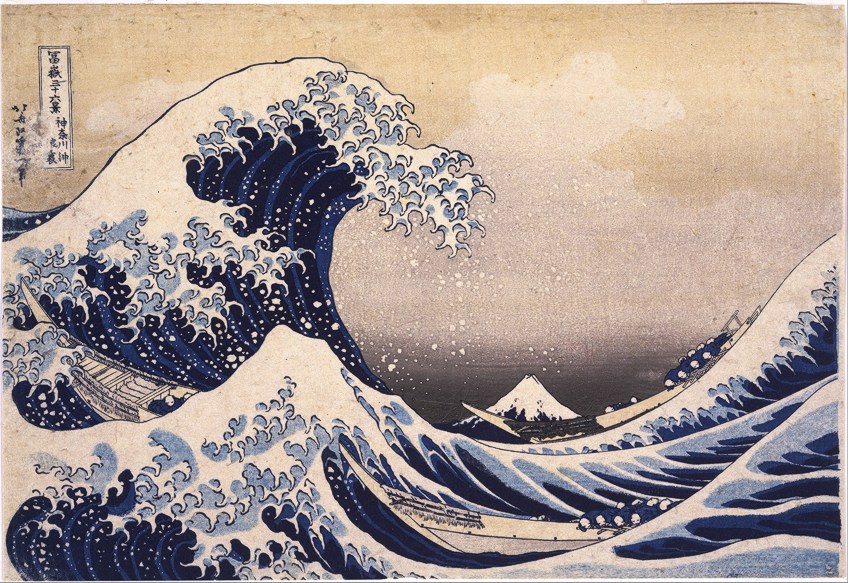

The Great Wave (1830)

| Name | Under the Wave Off Kanagawa |

| Year | 1830 |

| Size | 25 cm x 37 cm |

| Medium | Woodblock print |

1830 Hokusai began making what would become his most famous image when he was over 70 years old. The Great Wave off the Coast of Kanagawa (1830) is actually titled Under the Wave Off Kanagawa, though people generally call it The Great Wave. The color woodblock print The Great Wave produced roughly 8000 prints. The mass-produced poster-size prints were affordable and accessible, thanks to the democratic art form of Ukiyo-e.

This print is viewed as a quintessentially Japanese image, but it is a hybrid of Japanese and European styles. Hokusai arranged the picture so that Mount Fuji which is in the middle of the composition, and the highest point in Japan appears dwarfed by the humungous wave in the foreground.

Hokusai’s use of the then-new Prussian blue captures the brightness of the sea with a harmony of contrasts. There is a dynamic movement of the claw-like figures of the wave, which occupies two-thirds of the image. The foam from The Great Wave descends onto the mountain like snow falling onto the peak of Mount Fuji which remains covered all year round.

The Great Wave captures a distilled moment as this wave is about to crash down onto the three fragile boats beneath. Tossed about in the waves the three fast delivery boats are attempting to deliver a catch of live fish from a fishing fleet to the markets in Edo.

In Hokusai’s typical style, he depicts heroic working people and humanizes them through their encounter with nature and the uncertainty of whether they will make it to shore.

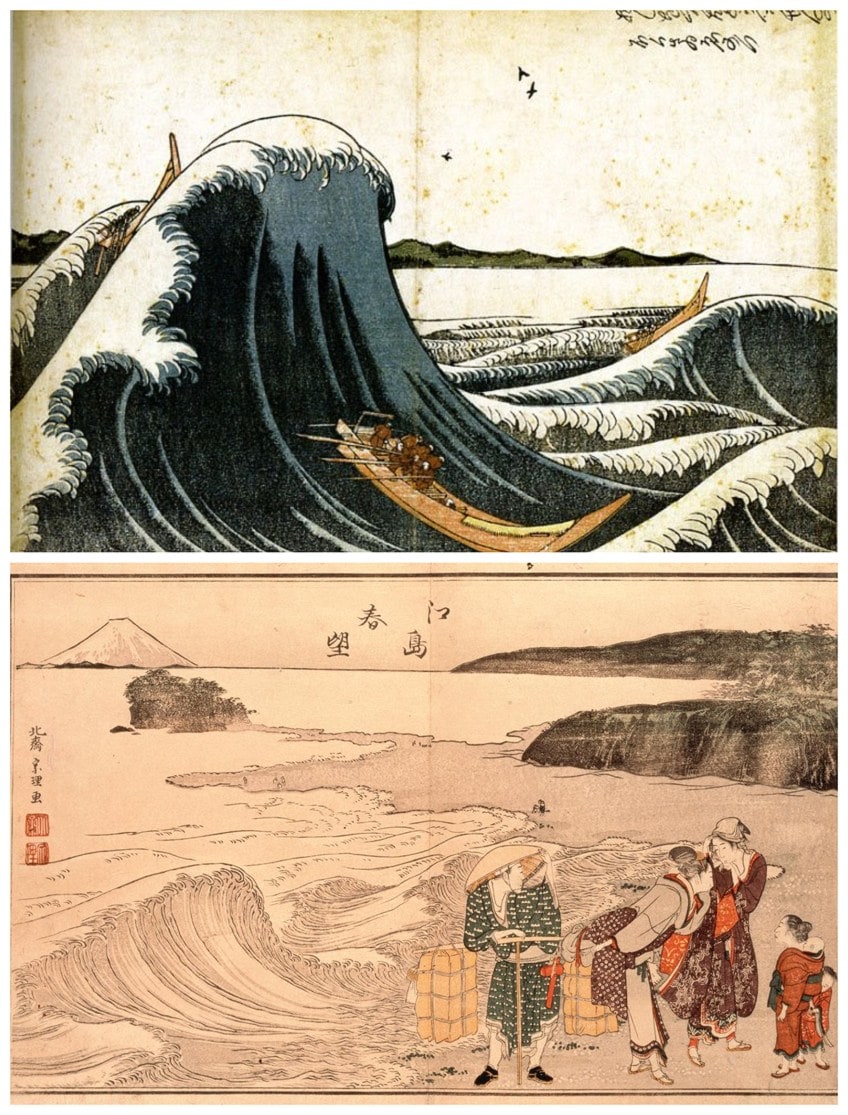

His earlier attempts at waves like Cargo Boat Passing Through Waves (1805), showing a big wave about to hit a boat, and another print, Spring at Enoshima (1797), which depicts a wave breaking at the beach, were fairly static in comparison. His earlier waves which were decades prior did not effectively register as water.

Kanagawa which is south of Edo shows a distance from Mount Fuji that has a hint of dread. Even though Japan remained isolated, the fear of invasion by sea was palpable. The rest of the world was being industrialized and the Japanese were concerned about foreign incursions. The ocean which had protected Japan’s peaceful isolation for two centuries was becoming its downfall.

Hokusai’s “Great Wave” encapsulates Japan’s fear of an uncertain future.

Red Fuji (c. 1830)

| Name | Red Fuji |

| Year | c. 1830 |

| Size | 25.4 x 36.5 cm |

| Medium | Woodblock print |

Fine Wind, Clear Morning is better known as Red Fuji (1830). In Hokusai’s earliest impressions, the red is quite light, almost faded. However, the blue outline on the edge of the mountain reveals that that coloring was not accidental. The more nuanced shade of red was harder to print for various reasons and the publishers began to cut corners which led to the implementation of the bright Red Fuji.

The original light red revealed the quality of light right before dawn. The bright red in this popular print is praised for its monumental and abstracted design. But the subtly is being missed. The triangular trees of the mountain forest seem to be printed from three different blocks. They bring depth through the various shades of green in which they were printed.

Interestingly, Hokusai’s most important print in Japan is not “The Great Wave” but “Red Fuji”. Since Mount Fuji is an important part of Japanese national identity, Japanese mountains art was popular. The Japanese did not want Fuji at a distance, but up close in its full glory.

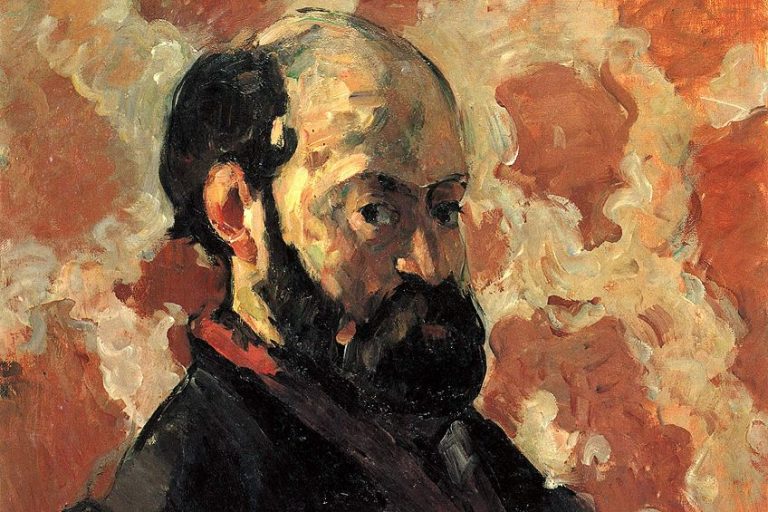

Modern Art

On July 8 1853 Japan’s self-imposed isolation came to an end when armed ships sailed uninvited into Tokyo harbor on behalf of the United States government demanding that the Japanese start trading with them. Japanese art which had developed independently for over two centuries was finally revealed to the rest of the world.

One of the reasons why Japanese art was the first non-Western art form to be “discovered” by the West was because it was partly Western. The images had their own aesthetic but they seemed rather familiar to the Western audience.

The French became fond of Japanese prints in the 1800s and this frenzy for Japanese art became known as Japonisme. It occurred shortly after Hokusai’s death in 1849. The obsession with Hokusai artworks and other famous Japanese artists like Kitagawa Utamoro, Utagawa Hiroshige, and Utagawa Kuniyoshi influenced European modern art.

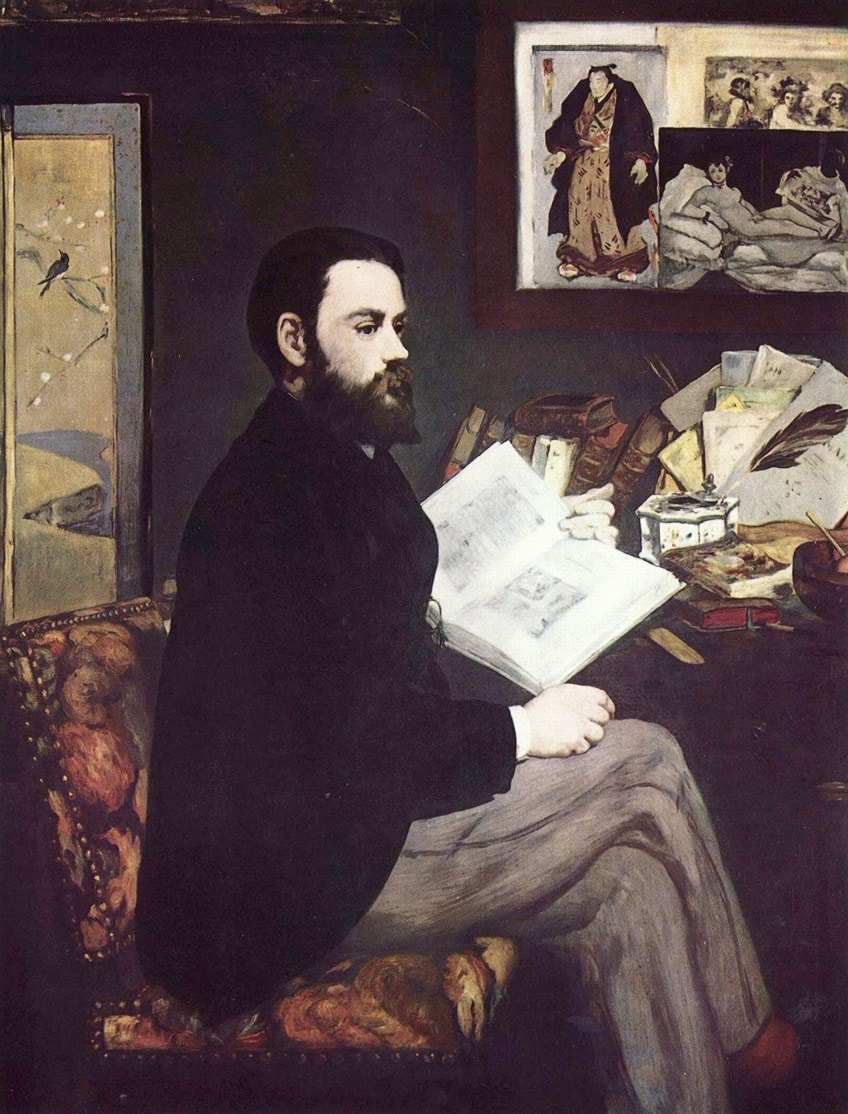

Vincent van Gogh would produce Starry Night (1889) which was greatly inspired by Hokusai’s Great Wave. In a letter, van Gogh wrote: “All my art is to some extent influenced by Japan.” Monet is among the many artists who expressed admiration for Japanese art. Monet owned 23 prints by Japanese artists. In Manet’s Portrait of Zola (1867-1868) you see the Utagawa Kuniaki II print Sumo Wrestler Omaruto Nadaemon of Awa Province (1860) clearly in the background.

The Japanese influence is present in Paul Gaugin’s The Wave (1888), Claude Monet’s La Japonaise (1876), Edgar Degas’ Madame Camus (1869-1870), Gustav Klint’s Posthumous Portrait of Ria Munk III (1917-1918), James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s Caprice in Purple and Gold: The Golden Screen (1864), Mary Cassatt’s Woman Bathing (1890-1891), Alphonse Mucha’s Winter (1896), and Pierre Bonnard’s Woman in Checkered Dress (1890-1891).

Although Japanese prints inspired Modernist artists, it is modernism that ultimately brought Japanese woodblock printing to an end. It persisted after western printing methods came to Japan surviving to around 1905 when woodblock prints finally gave way to new media such as lithography and photography.

However, in the 1910s, Ukiyo-e prints were somewhat revived as a classical art form.

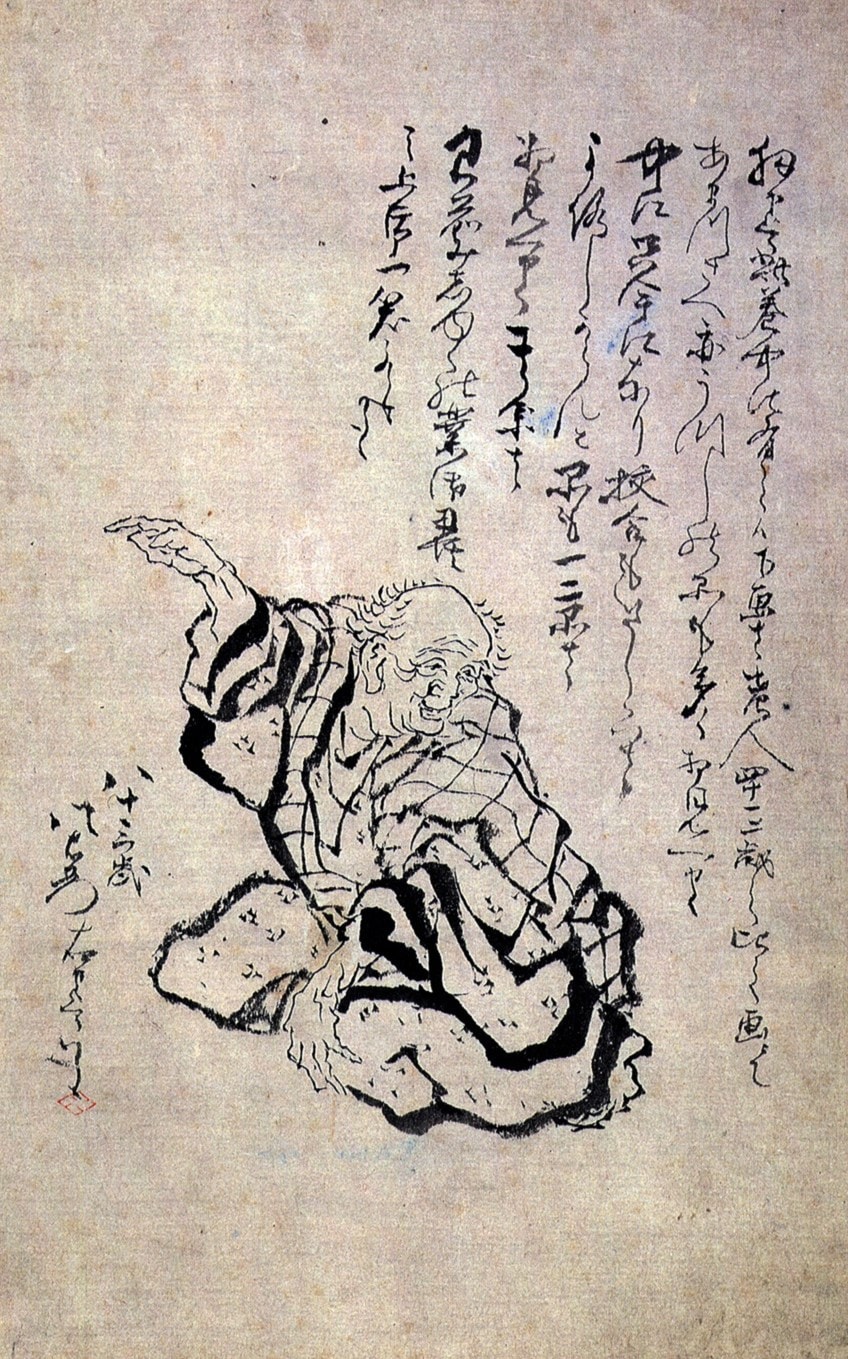

“The Old Man Crazy to Paint”

In 1834, Hokusai started calling himself Gakyō Rōjin, which means “the old man crazy to paint”. Hokusai produced some of his best work in these final decades. He had only begun Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji at the age of 70. As he said himself: “Until the age of 70, nothing I drew was worth notice. At 73 years, I was unable to fathom the growth of plants, trees and the structure of birds, animals, insects, and fish.”

Hokusai moved to Obuse when he was 83 and his eccentricities expanded. He worked from dawn to after dusk dedicating his life to art. He started his day with an exorcism which involved painting a Chinese lion on a piece of paper then throwing it out the window to ward off evil spirits. He stopped cleaning and would let his studio fester with dirt and clutter and when it became unbearable, he would simply move, which he was said to have done 93 times.

Hokusai paintings, sketches, and prints exceed the tens of thousands.

At 88, he began focusing on painting, signing his work with the character 100 and a red seal as a talisman for immortal life. He was convinced that he would live to 110 which he envisioned as his artistic prime. He wrote “if heaven will afford me five more years of life, then I will become a true artist.”

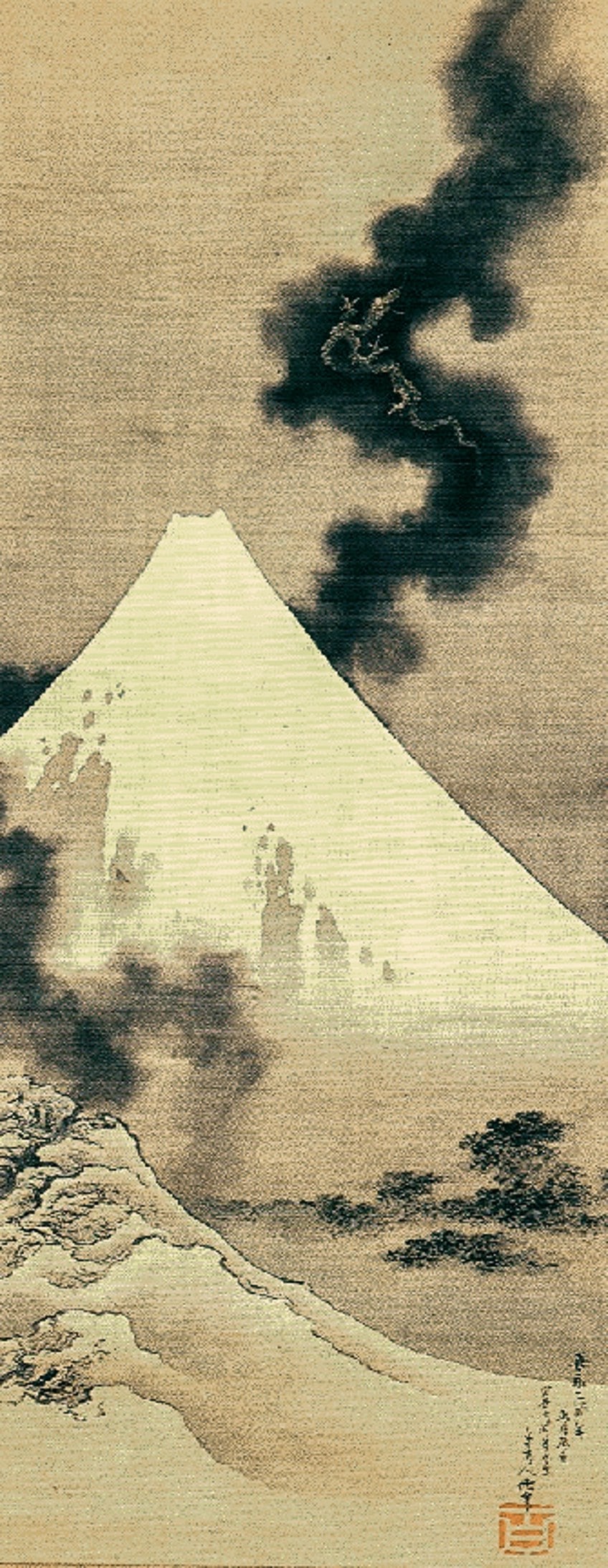

The last of the Hokusai paintings, Dragon flying over Mount Fuji (1849), was his actual peak. Though he had been painting dragons for decades, he finally seems to have cracked it in his 90s. The image synthesized the lessons of his long career. By using the tone of the paper as the highlights, he gave himself no room for error. His simplified Mount Fuji is mounted by a drifting dragon ascending into the heavens. It seems like a self-portrait. As if he is bidding his final farewell to the viewer.

In the inscription, Hokusai wrote: “…I was born in a dragon year, I’m painting this on a dragon day in my 90th year”. The Katsushika Hokusai biography would end that year, which proves that he continued experimenting and producing until his dying day. His tombstone bore his final pseudonym Gakyō Rōjin, the “Old Man Crazy to Paint”.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Many Prints Are in Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji?

This is a trick question because the series was so popular that Hokusai ended up making 10 more, so there are actually 46 in total. Additionally, Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji was so successful that it led to the commission of The 100 Views of Mount Fuji.

Was Hokusai Also a Performance Artist?

Yes. He was known to wow audiences with street performances during which he painted huge images spanning hundreds of feet using buckets of ink and a broom. He also entertained the royal court of the Tokugawa shōgun when he painted a large blue curve and then dipped a chicken’s feet in red pigment and chased it across the canvas.

Did Hokusai Work Alone?

No. Artists would only design the initial image and were not involved in the printing process. First, the publisher would commission the work, then the artist, then the block cutter, and the printer. Considering the fact that he also had followers, disciples, and students, Hokusai likely worked with a dedicated team of skilled craftsmen.

Did Hokusai Make Erotica?

Yes. One of Hokusai’s most well-known prints depicts a woman having sex with an octopus.

Can You Tell How Many Blocks Were Used by Looking at a Hokusai Print?

It can be difficult, but usually, if you can discern the number of colors, then that is an indication of how many blocks were used. Printers often risked using the same block if there was no chance of the two colors intermingling. They also used gradation and layering, which can make it hard to tell how many blocks were used.

Heidi Sincuba was the Head of Painting at Rhodes University from 2017 to 2020 and part of the first Artist Run Practice and Theory course at Konstfack in Stockholm, 2021. They completed their BFA at Artez Arnhem in the Netherlands, MFA at Goldsmiths University of London, and are currently a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Cape Town.

Heidi Sincuba’s own practice explores fugitivity through painting, drawing, text, textiles, performance, and installation. This praxis is founded on a conceptual intersection of biomythographic experimentation, existential automatism, and African ancestral knowledge systems. These methodologies of multiplicity result in a fluid and speculative aesthetic, continually manifesting and metamorphosing its material conditions.

Learn more about the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Thembeka Heidi, Sincuba, “Katsushika Hokusai – The Life and Works of This Famous Japanese Artist.” Art in Context. March 15, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/katsushika-hokusai/

Sincuba, T. (2022, 15 March). Katsushika Hokusai – The Life and Works of This Famous Japanese Artist. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/katsushika-hokusai/

Sincuba, Thembeka Heidi. “Katsushika Hokusai – The Life and Works of This Famous Japanese Artist.” Art in Context, March 15, 2022. https://artincontext.org/katsushika-hokusai/.