Abstract

Guided by the social-cognitive theory and self-determination theory, this study examined whether moral disengagement is indirectly associated with pro-bullying, passive bystanding, and defending, mediated by autonomous motivation, introjected motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation to defend victims of bullying among early adolescents. Participants were 901 upper elementary students from 43 school classes at 15 public schools in Sweden who completed a questionnaire in their classrooms. The results showed that students who were less inclined to morally disengage in peer bullying tended to be more autonomously motivated to take the victim’s side, which in turn was associated with greater defending and fewer pro-bullying behaviors. Introjected motivation to defend negatively mediated the association between moral disengagement and defending, and positively mediated moral disengagement’s associations with passive bystanding and pro-bullying behavior. Extrinsic motivation to defend mediated moral disengagement’s associations with passive bystanding and pro-bullying behavior. Finally, students who were more prone to morally disengage in peer bullying tended to be more amotivated to take the victim’s side, which in turn was associated with greater pro-bullying behavior and less defending.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

School bullying is a social phenomenon that is embedded in peer contexts (Hymel et al., 2015; Mischel & Kitsantas, 2020; Saarento et al., 2015; Salmivalli, 2010). Students are present as bystanders in most school bullying incidents (Craig et al., 2000; O’Connell et al., 1999). Here, a bystander is defined as any student who witnesses a bullying incident (Polanin et al., 2012), and can respond in at least three main different ways. Pro-bullying refers to taking the bullies’ side by participating in the bullying (i.e., assisting) or supporting the bullies by cheering and laughing (i.e., reinforcing). Passive bystanding refers to remaining passive and trying to stay outside the situation. Defending refers to taking the victim’s side by trying to help or support the victim (Jungert et al., 2016; Nocentini et al., 2013).

Bullying occurs more frequently in schools where classmates are inclined to engage in pro-bullying bystander behavior and is less prevalent in schools where classmates tend to defend the victims (Kärnä et al., 2010; Nocentini et al., 2013; Salmivalli et al., 2011). Thus, how peers respond to bullying matters (Salmivalli et al., 2011), and increasing our knowledge about moral disengagement and motivational factors related to various bystander responses to school bullying is crucial when designing and implementing school-based bullying interventions.

1.1 Moral disengagement and bystander behaviors

Defending a victim of bullying represents a proactive moral action that, “grounded in a humanitarian ethics, is manifested in compassion for the plight of others and efforts to further their well-being, often at personal costs” (Bandura, 2016, pp. 1–2). From early preschool years, children tend to judge behaviors that are unfair and harm others as wrong, regardless of whether rules exist, and as more seriously wrong than many other transgressions (Nucci, 2001). Studies have demonstrated that students, in general, condemn bullying (Levasseur et al., 2017; Thornberg et al., 2017a; van Goethem et al., 2010). However, knowing what is right and wrong is not sufficient for moral action. Students also need to be motivated to act and be capable of self-regulating themselves accordingly. Moral agency refers to the capacity to act in accordance with moral standards, such as helping others in need and refraining from behaving inhumanely and is—particularly in more risky situations, like being a bystander of school bullying—dependent on motivational and self-regulating processes (Bandura, 1999, 2016). Bullies are often powerful and tend to have a high status (Pouwels et al., 2016, 2018), and qualitative studies examining students’ perspectives on being a bystander in bullying situations have consistently reported that one reason for remaining a passive bystander instead of intervening is the fear of being attacked, victimized, or degraded in the social hierarchy and humiliated in front of other bystanders (Forsberg et al., 2014, 2018; Strindberg et al., 2020; Thornberg et al., 2018a).

According to the social-cognitive theory (Bandura, 1999, 2016), moral disengagement refers to a set of self-serving cognitive distortions by which self-regulation, guided by moral standards, can be deactivated. These self-serving cognitive distortions justify or explain away immoral and harming behavior such as bullying or downplay the sense of personal responsibility in the situation. In this way, moral disengagement demotivates moral actions and facilitates inhumane actions, including not taking the victim’s side but rather remaining passive or even taking the bully’s side as a bystander in bullying incidents, without any feelings of remorse, shame, or guilt. Moral disengagement includes mechanisms such as moral justification (i.e., using worthy ends or moral purposes to excuse pernicious means), diffusion of responsibility (i.e., diluting personal responsibility because other people are also involved), disregarding or distorting the harmful consequences of the actions, and blaming the victim (i.e., believing that the victim deserves their suffering). It is learned and can develop into trait-like habits or dispositions. Therefore, the tendency to morally disengage varies across individuals (Bandura, 2016; Bussey, 2020).

Moral disengagement is found to be positively associated with aggressive behaviors (for a meta-analysis, see Gini et al., 2014), including bullying (for a meta-analysis, see Killer et al., 2019). Regarding bystander responses to bullying, students who display higher levels of moral disengagement are more inclined to engage in pro-bullying (i.e., bystander behaviors that take the bully’s side, Bjärehed et al., 2020; Gini, 2006; Sjögren et al., 2021a, b; Thornberg et al., 2020) and are less likely to defend the victim (Doramajian & Bukowski, 2015; Jiang et al., 2022; Mazzone et al., 2016; Pozzoli et al., 2016; Sjögren et al., 2021a; Thornberg et al., 2017b). The negative association between moral disengagement and defending behavior has been confirmed in a recent meta-analysis, even though the effect size was small (Killer et al., 2019). While there is little research on the positive link between moral disengagement and pro-bullying, the link has consistently been revealed to be stronger compared to findings on the negative link between moral disengagement and defending. In a few studies, the latter link has failed to be significant (Sjögren et al., 2021b; Thornberg et al., 2020) or has been dependent on other variables (Bussey et al., 2020; Caravita et al., 2012).

Previous research on the relationship between moral disengagement and passive bystanding is even more inconsistent. Some studies have demonstrated a negative association (Gini, 2006; Thornberg & Jungert, 2013), while others have shown a positive association (Doramajian & Bukowski, 2015; Gini et al., 2015; Jiang et al., 2022; Sjögren et al., 2021a; Thornberg et al., 2017b) or a non-significant association (Mazzone et al., 2016). In their meta-analysis, Killer et al. (2019) found a non-significant relationship between the two variables. Research on this association is, however, scarce and findings are mixed. To further examine the relationships between moral disengagement and bystander behaviors in school bullying, it is important to consider how moral disengagement may motivate bystanders to intervene, and how various forms of regulation or motivation mediate the relationship between moral disengagement and different bystander behaviors. Adding a specialized theory on motivation might therefore be helpful when theorizing this issue, and when empirically examining the links between moral disengagement, motivation, and bystander behaviors.

1.2 Self-determination and different types of motivation to defend

Self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017) is a widespread theory on human motivation. It states that an individuals’ motivation to perform a certain task or engage in a particular behavior varies on a continuum of self-volition from amotivation (i.e., a lack of motivation) to intrinsic motivation (i.e., an individual is motivated to engage in an activity because they experience interest or enjoyment inherent in the activity), with four distinct types of motivations or regulations in between. Next to amotivation, external regulation is the least self-determined motivation as it refers to the classic case of extrinsic motivation, in which the individual behavior is controlled by external contingencies. Individuals strive to attain the desired outcome, such as tangible rewards or avoiding punishments (e.g., “to receive praise from my parents”).

Introjected regulation is more self-determined than external regulation but is still considered to be low in self-determination. It refers to a partially-internalized regulation where behavior is regulated by internal rewards, such as pride in success, and self-sanctions, such as guilt or shame for failure (e.g., “Because I feel like a bad person if I don’t help the student”). Hence, individuals control and pressure themselves to act in a way that is similar to being motivated by external controls, but the latter are instead replaced with internal contingencies. These behaviors are, thus, experienced as “internally controlling”.

In identified regulation, individuals are motivated to act because they recognize and identify with the perceived value of the behavior (e.g., “I stand up for the victim because it’s important to me that people around me feel safe and good” or “I defend the victim to make sure that people around me aren’t mean to others”). The regulation is more fully internalized and accepted as their own. They feel volition, autonomy, and self-determination because they behave in line with their identified values.

Finally, integrated regulation not only includes identification with the value of the behavior but also fully integrates this identification with other aspects of the self and its core interests and values (e.g., “I defend someone who is bullied because that’s the kind of person I am”). Identified regulation and integrated regulation are high in self-determination and are often merged into a single construct called autonomous motivation in the literature (Ryan & Deci, 2017). As Ryan and Deci (2017) put it, “behaviors are autonomously motivated to the extent that the person experience volition—to the extent that he or she assents to, concurs with, and is wholly willing to engage in the behaviors. When autonomous, behaviors are experienced as emanating from, and an expression of, one’s self” (p. 14). In other words, there is a high level of agency in motivation, self-regulation, and behavior (cf., Bandura, 2016).

Research has demonstrated that autonomous motivation is linked to stronger persistence and performance compared with external and introjected regulations (often called controlled motivation) in domains such as academic learning and achievement (Niemiec & Ryan, 2009; Taylor et al., 2014), health behavior change (Ng et al., 2012), and work performance (Moran at el., 2012). In addition, autonomous motivation has been shown to be associated with actual prosocial behavior (Hardy et al., 2015).

In the context of being a bystander of school bullying, only a few studies have examined these various forms of motivation. Jungert et al. (2016) found that autonomous motivation was linked to greater defending and less passive bystanding, while extrinsic motivation (external regulation) was associated with greater pro-bullying. Longobardi et al. (2020) examined whether the linkage between empathy and defending was mediated by autonomous motivation, introjected regulation, and external regulation. Although empathy was associated with greater autonomous motivation and introjected regulation and less external regulation, only autonomous motivation was associated with greater defending. However, because empirical studies on how various forms of motivation might be linked with different bystander behaviors in school bullying are still limited, there is a need to further examine these possible associations. In addition, none of the previous studies have examined the link between amotivation and bystander behaviors in school bullying.

With reference to the self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017), in our study, autonomous motivation refers to integrated and identified regulation, introjected motivation refers to introjected regulation, and extrinsic motivation refers to external regulation. To our knowledge, the current study is the first to integrate the social-cognitive theory of moral disengagement and the self-determination theory of motivation in the domain of being a bystander in school bullying, and to examine whether the associations between moral disengagement as a trait-like habit and bystander behaviors are mediated by autonomous motivation, introjected motivation, extrinsic motivation, or amotivation.

According to the social-cognitive theory, moral disengagement interferes with motivational and self-regulatory processes, which in turn affects to what extent individuals engage in moral and immoral behaviors (Bandura, 2016). Moral disengagement “permits weakness of will and/or self-interested desires to thwart their moral motivation to abide by their moral judgement” (Peeters et al., 2019, p. 430). In other words, the propensity to morally disengage, as it has been developed into a trait-like or routinized pattern of cognitive distortion in moral judgment, should influence what kind of motivation to act a bystander experiences when witnessing bullying. In this way, the links between moral disengagement and various bystander behaviors may be mediated through motivational and self-regulatory mechanisms, such as autonomous motivation, introjected motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation.

Even though moral disengagement might be positively associated with amotivation to defend victims of school bullying, this has not yet been empirically tested. It is also still unclear whether moral disengagement is associated with autonomous motivation, introjected regulation, and extrinsic motivation to defend victims of school bullying. According to the social-cognitive theory (Bandura, 1999, 2016), it would be plausible to assume that moral disengagement is negatively related to introjected regulation. The theory assumes that high levels of moral disengagement deactivate self-regulation of behavior by disengaging moral self-sanctions such as feelings of guilt and shame. However, the self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017) argues that this regulation is rather low in self-determination and, in accordance with research in several domains, less persistent and successful in performance than autonomous motivation, which is high in self-determination. Thus, even the though—referencing to the social-cognitive theory—we expect a negative link between moral disengagement and introjected motivation (regulated by positive self-rewards and negative self-sanctions), with reference to the self-determination theory, we expect an even stronger negative association between moral disengagement and autonomous motivation.

1.3 The current study

To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first that aims to examine whether moral disengagement is indirectly associated with pro-bullying, passive bystanding, and defending, mediated by autonomous motivation, introjected motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation to defend victims of bullying among early adolescents. In view of previous research on moral disengagement and bystander behaviors, we found it plausible to expect that moral disengagement overall would be associated with greater pro-bullying and less defending. Despite the novelty of this study, we formulated a set of hypotheses constructed as a conceptual model (see Fig. 1).

We hypothesize that moral disengagement will be positively associated with amotivation since this motivation construct (“Nothing can motivate me to help someone who is bullied”) seems to manifest a habit or disposition of moral distortions (cf., Bandura, 2016); amotivation, in turn, will be positively associated with pro-bullying and passive bystanding, and negatively associated with defending.

We also hypothesize that moral disengagement will be positively associated with extrinsic motivation since this motivation construct (“What’s in it for me?” or “I would only be motivated to help the victim if I get rewarded or if it helps me to avoid a punishment”) also appears to manifest a habit or disposition of moral distortions (cf., Bandura, 2016). While we hypothesize that extrinsic motivation to defend, in turn, will be positively linked to all three bystander behaviors, we expect it to have a stronger link to passive bystanding than to the other two bystander behaviors, because passive bystanding maximizes punishment avoidance.

Defending may result in social rewards, such as an increase in social status (perceived popularity) and likeability (sociometric popularity or social preference). Defenders tend to score high in both these dimensions of popularity (Caravita et al., 2009, 2010; Pouwels et al., 2016; Pöyhönen et al., 2010), although the positive link between social status and defending seems to decline with age (Caravita et al., 2009; Pouwels et al., 2016). Pro-bullying, on the other hand, may result in social rewards as well, such as an increase in social status by being accepted and recognized by and associated with powerful and high-status bullies. For example, Pouwels et al. (2016) found that students who usually took the bullies’ side (i.e., pro-bullies) tended to have high social status, even though they were somewhat less powerful and visible than the bullies, and less liked than peers who more often defended victims or remained passive.

In contrast to defending and pro-bullying, passive bystanding is the safest option for students who are highly externally regulated in bystander situations. It helps them to avoid punishment (e.g., being attacked, victimized, or degraded in the social hierarchy and humiliated in front of other bystanders; cf., Strindberg et al., 2020) executed by powerful bullies, who tend to be the most aggressive students with the highest social status (Pouwels et al., 2016, 2018), and their followers. This is the risk of defending. At the same time, passive bystanding also helps students to avoid punishment (e.g., reprimands, disciplinary consequences, or reports to their parents) meted out by teachers and other school personnel, and in terms of avoiding social disapproval from other peers (i.e., those who are neither bullies nor followers) and a decrease in likeability associated with being a follower of bullies (cf., Pouwels et al., 2016). This is the risk of pro-bullying. Remaining passive and trying to stay outside is a response that helps bystanders to avoid all these possible social costs or sanctions.

Finally, we hypothesize that moral disengagement will be negatively associated with both autonomous motivation and introjected motivation. Both these forms of motivation, in turn, would be positively associated with defending and negatively associated with pro-bullying and passive bystanding. We also hypothesize that autonomous motivation will be a stronger mediator than introjected motivation between moral disengagement and defending since the autonomous motivation to defend should indicate higher self-determination (cf., Ryan & Deci, 2017), which is needed to be persistent and resist fear, peer pressure, and powerful bullies and followers, and thus, a stronger moral agency in bystander situations (cf., Bandura, 1999, 2016).

2 Method

2.1 Participants and procedure

The participants in this study included 901 students from 43 upper elementary school classes at 15 public schools in various socio-geographic areas from rural areas to midsize cities in Sweden (age range = 9–13 years old, M = 11.00, SD = 0.83; 279 [31%] fourth-graders, 325 [36%] fifth-graders, and 297 [33%] sixth-graders; in Sweden, students begin fourth grade the year they turn 10). Of these, 465 (52%) were boys and 436 (48%) were girls. Socioeconomic background was not directly measured in the study, but the sample of public schools represented a wide range of socioeconomic backgrounds. Most participants were of Swedish ethnicity, and only a minority (16%) had an immigrant background (i.e., they were born in another country or at least one of their parents was born in another country). The original sample consisted of 996 students (513 boys [52%] and 483 [48%] girls; thus, the gender ratio was found to be the same between the original sample and the final sample). However, 95 of these (10%) did not participate in the study for various reasons: 74 because they did not obtain parental consent, 19 because they were absent due to sickness during data collection, and two because they did not want to. The participation rate was evenly spread over grades and genders. We obtained informed parental consent and student assent from all 901 participating students.

Participants anonymously completed a questionnaire in their ordinary classroom setting. A team of master student-teachers was recruited and instructed to administrate the data-gathering sessions. They were present throughout the session (one student teacher in each classroom), explained the study procedure, reassured participants of the anonymous nature of the study, and assisted those who needed help. They also informed the participants that they had the option of withdrawing from the study at any time. The session took about 20–30 min in each classroom.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Gender and age

Participants completed a sociodemographic scale that included questions about their gender (0 = girl, 1 = boy) and age (i.e., “How old are you?”, followed by, “I’m …… years and …… months old”).

2.2.2 Bystander behavior

A 15-item bystander behavior scale (Thornberg et al., 2017b) was used to measure bystander behavior in bullying situations. The participants were asked, “Try to remember situations in which you have seen a student being bullied (for example: teased, mocked, physically assaulted, or frozen out). What do you usually do?” Five items described pro-bullying (e.g., “I start to bully the student too”, “I laugh and cheer the bullies on”, “I encourage the bullies by shouting and laughing”; Cronbach’s α = 0.82); five items described passive bystanding (e.g., “I just walk away”; “I don’t do anything specific”, “I stay away”; Cronbach’s α = 0.78); and five items described defending (e.g., “I tell them to stop fighting with the students”, “I tell a teacher”, “I comfort the bullied student”; Cronbach’s α = 0.80). The response options for each item were on a four-point scale: strongly disagree (1), partly disagree (2), partly agree (3), and strongly agree (4). Because we intended to measure participants’ self-reports of how they typically responded when they had witnessed bullying, the items were measured on an “agree–disagree” scale, as opposed to a “never–always” scale. The latter type of wording might increase the risk of confounding with the perceived frequency of witnessing bullying. The three-dimensional scale was confirmed by a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and the model had a good fit with the data (CFA: χ2 /df = 306/74, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.059[0.052, 0.066], CFI = 0.94, SRMR = 0.05).

2.2.3 Moral disengagement

Thornberg and Jungert’s (2013) 6-item moral disengagement in bullying scale was used to measure how inclined participants were to morally disengage in bullying situations (e.g., “Bullying is okay in certain cases”, “Some people deserve to be bullied”). The response options for each item were on a seven-point scale: strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). The six items were averaged into one scale score (Cronbach’s α = 0.80). The one-dimensional scale was confirmed by a CFA that had a good fit with the data (CFA: χ2/df = 109/9, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.011[0.093, 0.130], CFI = 0.95, SRMR = 0.04).

2.2.4 Motivation to defend

A four-dimensional 14-item scale was developed to measure the participants’ motivation to defend a victim of bullying. The participants were asked: “What makes you want to help a bullied student?” Four items described autonomous motivation (“Because I think it’s important to help people who are mistreated by others”, “Because I’m a person who cares about others”, “Because I think it’s important to fight violence, oppression, and injustice”, and “Because I’m a person who clearly speaks up when others behave badly towards someone”; Cronbach’s α = 0.70). Two items described introjected regulation (“Because I feel like a bad person if I don’t help the student” and “Because if I don’t help, I will feel guilty in a troublesome way”; Spearman-Brown coefficient = 0.66). Five items described extrinsic motivation (“To get praise from teachers”, “To get praise from other students”, “To get friends”, “To avoid a telling-off from teachers”, and “To get praise from my parents”; Cronbach’s α = 84). Three items described amotivation (“Nothing, because I don’t want to help bullied students”, “There is nothing that can make me want to help the student”, and “Honestly, I don’t know anything that would make me want/willing to help”; Cronbach’s α = 0.66). The response options for each item were on a four-point scale: strongly disagree (1), partly disagree (2), partly agree (3), and strongly agree (4). The four-dimensional scale was confirmed by a CFA that had a good fit with the data (CFA: χ2/df = 252/71, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.053[0.046, 0.060], CFI = 0.95, SRMR = 0.04).

2.3 Data analysis

Analyses of normal distribution and pairwise correlations between all investigated variables constituted the first stage of analysis. In the second stage of analysis, structural equation modeling with Mplus Version 8.3, based on the analysis of the covariance matrix, was utilized to examine the hypothetical causal model, which postulated that the construct (latent factor) of moral disengagement is related to the constructs (latent factors) of the four types of motivation to defend, which in turn are related to the three outcomes: defending, passive bystanding, and pro-bullying (latent factors). We also controlled for gender in the model. All observed variables were ordinal; therefore, they were analyzed as ordered categories, and in that case, estimations perform better using WLSMV, even when data are not normally distributed. Five statistics of model fit were used: the Comparative Fit Index (CFI); TFI; χ2 divided by the number of degrees of freedom (χ2/df); the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) with a 90% confidence interval; and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Bentler (1995) recommends that an acceptable best-fitting model should have a CFI > 0.90, a TFI > 0.90, a χ2/df < 3, a RMSEA < 0.06, and a SRMR < 0.08. We also tested the model using CONFIGURAL, METRIC, and SCALAR, as some of the variables we used tend to be not normally distributed.

Finally, the third stage of analysis consisted of mediation analyses. To determine whether the type of regulation to defend mediated the relationship between moral disengagement and participant role, we tested nine mediation pathways. These analyses were performed using the Jamovi software (Jamovi Project, 2019).

3 Results

3.1 Preliminary results

The normal distribution of the of the study population variables was examined using the standardized skewness and kurtosis values (the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests were not used as they may be unreliable when the sample size is larger than 300). Acceptable values of skewness fall between − 3 and + 3, and kurtosis is appropriate from a range of − 10 to + 10 when utilizing SEM (Brown, 2006). All variables except for moral disengagement (skewness = 3.62 and kurtosis = 16.30) and pro-bullying (skewness = 4.45 and kurtosis = 27.00) were within the acceptable ranges. After examining Q-Q plots for all variables, it was concluded that only moral disengagement and pro-bullying had floor effects.

Pairwise correlations are presented in Table 1. Moral disengagement was positively correlated with amotivation, extrinsic motivation, passive bystanding, and pro-bullying, while it was negatively correlated with autonomous motivation, introjected regulation, and defending. It is important to note that its associations with the variables were weak, with the exceptions of amotivation, which was moderate, and pro-bullying, which was strong (Cohen, 1988). As expected, the negative correlation with introjected regulation was weaker than with autonomous motivation.

Autonomous motivation and introjected motivation, in turn, were positively correlated with defending, while they were negatively correlated with passive bystanding and pro-bullying. Of note, autonomous motivation was more strongly correlated than introjected motivation in all three bystander responses. Extrinsic motivation and amotivation were positively correlated with passive bystanding and pro-bullying, while amotivation was negatively correlated with defending.

Regarding gender, boys were more inclined to score higher on moral disengagement, extrinsic motivation, amotivation, and pro-bullying, and less on autonomous motivation, introjected motivation and defending. Finally, age was not significantly correlated with any other variable, with the exception of two variables: it was positively correlated with introjected motivation and negatively correlated with defending.

3.2 Structural equation modelling

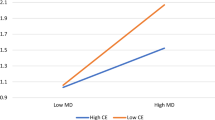

To test the hypothetical model (see Fig. 1), a structural equation model was created. Because gender had several significant correlations, albeit small (notably external regulation and amotivation), while age none except for two very small correlations, we included gender but not age as a control variable in the model. There were no important differences when the model was tested with CONFIGURAL, METRIC, and SCALAR (CFI = 0.95 in all three models), and the tested model had overall good fit: χ2/df = 1422.02/562, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.041[0.039, 0.044], CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.94, SRMR = 0.059. Figure 2 displays a representation of this model with the stdyx standardized statistics reported. Moral disengagement was negatively associated with autonomous motivation (b = - 0.41, p < .001), and introjected motivation (b = - 0.25, p < .001) while positively associated with extrinsic motivation (b = 0.35, p < .001) and amotivation (b = 0.56, p < .001). Autonomous motivation was positively associated with defending (b = 0.97, p < .001) and negatively associated with passive bystanding (b = - 0.52, p < .001) and pro-bullying (b = - 0.31, p = .001). Introjected regulation was positively associated with defending (b = 0.19, p = .010). Extrinsic motivation was positively associated with passive bystanding (b = 0.26, p < .001). Finally, amotivation was not significantly associated with any role.

We controlled for gender in the model and gender was significantly associated with pro-bullying (b = 0.14, p = .005), passive bystanding (b = 0.10, p = .005), amotivation (b = 0.12, p = .018), extrinsic motivation (b = 0.14, p < .001), autonomous motivation (b = − 0.11, p = .013), and moral disengagement (b = 0.18, p < .001). In other words, boys were more prone than girls to score higher on pro-bullying, passive bystanding, amotivation to defend, extrinsic motivation to defend, and moral disengagement, and less on autonomous motivation to defend.

3.3 Mediation path analyses

To determine whether the type of regulation to defend mediated the relationship between moral disengagement and participant role, we tested nine mediation pathways. These analyses were performed using the Jamovi software (Jamovi Project, 2018).

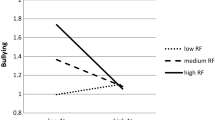

Autonomous motivation mediated the relationship between moral disengagement and defending (b = - 0.14, SE = 0.03, p = .012, 95%CI = [- 0.12, - 0.01]) and pro-bullying (b = 0.02, SE = 0.00, p < .003, 95%, CI = [0.18, 0.24]). Introjected motivation, in turn, mediated the relationship between moral disengagement and defending (b = - .05, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001, 95%, CI = [- 0.07, - 0.02]), passive bystanding (b = 0.03, SE = 0.01, p < .001, 95%, CI = [0.01, 0.04]), and pro-bullying (b = 0.45, SE = 0.01, p < .001, 95%, CI = [0.00, 0.01]).

Extrinsic motivation did not mediate the relationship between moral disengagement and defending, but did mediate the relationships between moral disengagement and passive bystanding (b = 0.10, SE = 0.03, p = .002, 95%, CI = [0.04, 0.16]) and pro-bullying (b = 0.49, SE = 0.01, p < .001, 95%, CI = [0.20, 0.26]). Finally, amotivation mediated the association between moral disengagement and defending (b = - 0.12, SE = 0.03, p < .001, 95%, CI = [- 0.18, - 0.05]) and pro-bullying (b = 0.42, SE = 0.01, p < .001, 95%, CI = [0.17, 0.23]).

4 Discussion

There appears to be a significant knowledge gap in terms of how moral disengagement may affect students’ motivation to defend victims of school bullying, and how this process, in turn, may influence their actual bystander behavior. To our knowledge, the present study was the first to examine whether moral disengagement is indirectly associated with pro-bullying, passive bystanding, and defending, mediated by autonomous motivation, introjected motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation to defend victims of bullying among early adolescents.

4.1 Moral disengagement and motivation

Consistent with what we hypothesized, we found that students with higher levels of moral disengagement were more inclined to be amotivated and extrinsically motivated to defend victims of bullying, and less autonomously and introjectedly motivated to defend them. Our results suggest that students who are high in moral disengagement would not see any reason why they should intervene, or would only be motivated to intervene if they thought that it would benefit them in terms of helping them to attain social rewards or avoid social sanctions. Thus, the present study contributes to the literature by shedding light on how moral disengagement weakens or undermines self-determination to defend a victim when students happen to be bystanders in bullying situations. By contrast, students who were less inclined to morally disengage seemed to be more motivated to defend, both in terms of autonomous and introjected motivation. In other words, lack of or low moral disengagement (Bandura, 1999, 2016) makes room for high self-determination (Ryan & Deci, 2017) and high affective self-evaluative reactions (Bandura, 2016) among students to defend victims in their role as a bystander.

Bandura (1999, 2016) emphasizes that moral standards are linked to moral action through self-regulating processes that produce a sense of self-worth when individuals recognize that they are doing right, and produce a sense of guilt and self-condemnation when they recognize that they are doing wrong. These consequences, in turn, motivate moral actions (Bandura, 1999, 2016), which correspond to introjected motivation within self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017). Accordingly, our study found a negative association between moral disengagement and introjected motivation; but in line with self-determination theory and what we hypothesized, this link was weaker compared to the link between moral disengagement and autonomous motivation in the SEM model. In other words, our findings suggest that moral disengagement seems to decrease autonomous motivation to defend more than introjected motivation to defend.

Overall, our findings contribute to the literature by demonstrating how the social-cognitive theory of moral disengagement (Bandura, 2016) and self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017) might be integrated to better understand students’ motivation to defend a victim when they are witnesses to bullying.

4.2 Motivation and bystander behaviors

The present findings showed that autonomous motivation and introjected motivation were associated with greater defending. Autonomous motivation had the strongest association with defending. Our findings can be compared with previous research showing that autonomous motivation is related to greater defending (Jungert et al., 2016; Longobardi et al., 2020). This is in line with self-determination theory, which states that high autonomous motivation indicates high self-determination (Ryan & Deci, 2017), and with previous research showing that autonomous motivation is associated with stronger persistence and performance in other activities (Jungert et al., 2015; Moran et al., 2012; Ng et al., 2012; Niemiec & Ryan, 2009; Taylor et al., 2014), including prosocial behavior (Hardy et al., 2015).

In addition to an autonomous motivation to defend, our findings revealed that introjected motivation to defend was also linked to greater defending as well, which supports social-cognitive theory (Bandura, 2016). According to Bandura (1999, 2016), self-approvals and self-sanctions (i.e., introjected regulation, see Ryan & Deci, 2017) keep conduct in line with moral standards. In the current study, it motivated students’ moral behavior in terms of defending. Overall, our findings suggest the importance of both high autonomous and introjected motivation to defend victims of bullying, as both are positively related to actual defending in bullying situations.

Furthermore, the findings revealed that extrinsic motivation was associated with greater passive bystanding, while autonomous motivation was negatively linked to this bystander response. The negative association between autonomous motivation and passive bystanding proposes that students who are low in autonomous motivation seem to be less self-determined and persistent in their moral conduct as bystanders, compared with students who are high in autonomous motivation. These findings are consistent with self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017) and self-determination research in other activities or domains (e.g., Jungert et al., 2015, 2022; Moran et al., 2012; Ng et al., 2012).

The positive relationship between extrinsic motivation and passive bystanding, in turn, suggests that students who only consider defending a bullying victim if it would benefit themselves (i.e., help them to attain social rewards or avoid social sanctions) would be those who are most inclined to remain passive bystanders when witnessing bullying. Considering that bullies are usually powerful and high-status peers (Pouwels et al., 2016, 2018), fear of social sanctions in terms of being attacked, victimized, and humiliated in front of others as a consequence of intervening (cf., Strindberg et al., 2020; Thornberg et al., 2018a) might make these students more prone to remain passive. By comparison, students who are high in autonomous motivation might be less occupied with and influenced by social costs as possible outcomes of defending the victim.

The fact that the only bystander behavior that was significantly related to extrinsic motivation in the SEM model was passive bystanding supports our hypothesis that students who are highly externally regulated in bystander situations may be inclined to consider passive bystanding to be the safest option because it maximizes punishment avoidance in a risky situation. Students who are high in extrinsic motivation might believe that remaining passive is a neutral bystander response that offers avoidance of being attacked, victimized, or humiliated in front of others by powerful bullies (which might be a calculated risk if they try to defend the victim). Simultaneously, they might also think that doing nothing and trying to stay outside can help them to avoid social disapproval from most, many, or significant non-bullying peers (which might be the calculated risk of pro-bullying), and avoid reprimands, disciplinary consequences, and reports to their parents (which might be the calculated risk of pro-bullying as well, if it comes to teachers and other school staff’s knowledge).

Furthermore, we found that less autonomous motivation is associated with greater pro-bullying. This was the only form of motivation that was significantly linked with taking the bullies’ side in the SEM model. Thus, our model suggests that autonomous motivation is the most important form of motivation in explaining the variance of all three bystander behaviors of school bullying. Not only does it increase the likelihood that bystanders intervene to help the victim but also decreases the risk that they remain passive bystanders or side with the bullies.

Finally, even though amotivation to defend correlated negatively with defending and positively with passive bystanding and pro-bullying, which suggests that students who lack the motivation to defend (i.e., “nothing can motivate me to help someone who is bullied”) are less inclined to defend and more prone to remain passive or side with the bullies, when all forms of motivation were included in the same model, amotivation became insignificantly related to all three bystander behaviors. One possible explanation is that autonomous motivation in particular, but also introjected motivation and extrinsic motivation to defend are much more important forms of motivation in explaining variance in bystander behaviors than amotivation.

4.3 Moral disengagement and bystander behaviors mediated by motivation

Previous research has shown that students who are high in moral disengagement tend to score high in pro-bullying (e.g., Bjärehed et al., 2020; Sjögren et al., 2021a, b; Thornberg et al., 2020) and low in defending (e.g., Jiang et al., 2022; Killer et al., 2019; Sjögren et al., 2021a), but inconsistent findings regarding passive bystanding (e.g., Jiang et al., 2022; Killer et al., 2019; Mazzone et al., 2016; Sjögren et al., 2021a; Thornberg & Jungert, 2013). However, the current study is the first to demonstrate the mediating role of various degrees of self-determined motivations in the association between moral disengagement and bystander behavior in bullying situations.

4.3.1 Autonomous and introjected motivation

The mediation analysis regarding autonomous motivation as a possible mediator showed that students who were less inclined to morally disengage in peer bullying tended to be more autonomously motivated to take the victim’s side, which in turn was associated with greater defending and less pro-bullying. By contrast, students who were more prone to morally disengage in peer bullying situations were less inclined to be autonomously motivated to defend, which in turn was linked to greater pro-bullying and less defending. Thus, the degree of autonomous motivation seems to play a key role as a mediator between moral disengagement and the two bystander behaviors where the bystander takes a clear stand: taking the victim’s side versus taking the bullies’ side.

The importance of the autonomy orientation in predicting prosocial behavior has been emphasized in the self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017) and confirmed empirically (Hardy et al., 2015), and can be labeled moral self-determination (Curren & Ryan, 2020). It is therefore not a surprise that moral disengagement is mediated through autonomous motivation to both moral behavior (defending) and immoral behavior (pro-bullying) when students are bystanders in bullying situations. Autonomous motivation to defend a bullying victim is an example of moral motivation that refers to a “reason-responsive appropriate valuing of, or responsiveness to, everything of moral value, beginning with persons, their well-being, and what is important to their well-being” (Curren & Ryan, 2020, p. 298). Moral disengagement undermines moral motivation to help a victim, which seems to make students not only less inclined to engage in moral behaviors (helping the victim) but also more prone to engage in immoral behaviors (inflicting harm) in bystander situations.

Moreover, the mediation analysis showed that introjected motivation to defend negatively mediated the association between moral disengagement and defending, and positively mediated moral disengagement’s associations with passive bystanding and pro-bullying. Thus, the mediation analysis supports the social-cognitive theory: self-approvals and self-sanctions are motivational components in the self-regulatory processes whereby moral standards are translated into moral action (Bandura, 2016).

4.3.2 Extrinsic motivation and amotivation

According to the mediation analysis, extrinsic motivation to defend mediated moral disengagement’s associations with passive bystanding and pro-bullying. Moral disengagement makes students more prone to ask themselves, as bystanders, “What’s in it for me?”, and either remain passive or stay outside to avoid social sanctions (e.g., “I don’t want to put myself at risk and get into trouble”) or take the powerful bullies’ side to receive social approval from them (e.g., “I want the popular peers to like me and maybe even include me in their popular peer group”).

Finally, mediation analysis regarding amotivation as a possible mediator showed that students who were more prone to morally disengage in peer bullying tended to be more amotivated to take the victim’s side, which in turn was associated with greater pro-bullying and less defending. While the autonomous motivation to defend can be considered a moral motivation, amotivation to defend can be viewed as an immoral motivation (lack of caring and compassion for other people’s suffering and wellbeing). Thus, both moral motivation and immoral motivation were mediating variables in the path from moral disengagement to both moral behavior (defending) and immoral behavior (pro-bullying) in the role of a bystander in bullying events.

4.4 Limitations

Some limitations of this study should be noted. Data were collected using self-reporting measures, which are susceptible to social desirability, perception and recall biases, and shared method variance effects. Furthermore, a cross-sectional study design was adopted; therefore we were unable to determine the direction of effects between the variables. Given the social cognitive theory’s assumptions about the interplay between environmental, individual, and behavioral influences (Bandura, 2016), it is, for example, not clear whether moral disengagement is a predictor of amotivation to defend, or if amotivation to defend predicts the propensity to morally disengage as a bystander. It is also possible that the associations found in the study are reciprocal. Future research needs to take a longitudinal approach to examine directionality, including possible bidirectional relationships, among the study variables.

Another limitation is that the amotivation scale had a low Cronbach’s alpha value, which means that some caution is warranted when analyzing results that concern a lack of motivation. However, all other variables had acceptable alpha values. Considering that personal, behavioral, and environmental influences interact with and influence each other (Bandura, 2016), further research should examine how the associations found in the current study might interact with or be moderated by situational or environmental factors. For instance, autonomous and extrinsic motivations to defend are associated with whether the victim is an ingroup or outgroup member (Jungert & Perrin, 2019).

An additional limitation is that moral disengagement and pro-bullying were very skewed and appeared to suffer from floor effects. This might be explained partially by their possibly low incidence among the students, and partially in terms of underreporting, even though participants were reassured that their answers were completely anonymous. Our study is, therefore, vulnerable to underestimations of associations where these variables were included. Altogether, the model in the study should be interpreted with caution.

One further possible limitation is that the bystander scale assumes that the students have seen or observed physical, verbal, or relational peer aggression, which might not always be the case. On the other hand, bullying and other forms of peer aggression are present in Swedish schools (Friends, 2022; Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention, 2018), and it would be unlikely that students never witnessed such negative behavior. In addition, the trained student-teachers who administered the questionnaires and assisted the participants in the classrooms did not report any problems with completing the bystander scale. Finally, a note of caution needs to be sounded regarding the generalization of the findings, as the study sample consisted of 901 students from rural areas to midsize cities in Sweden. Future studies might expand on the current findings by considering students at schools that are located in large metropolitan areas and in other countries.

4.5 Implications for practice

These limitations aside, the current findings have implications for practice in the school setting. It is incumbent upon school-based practitioners to thoroughly assess students’ moral (dis)engagement as well as their motivations to defend victims of bullying. Because moral disengagement is linked not only to bullying and aggressive behavior but also to bystander behavior, practitioners are advised to thoroughly assess motivations underlying not only bullying but also bystander behaviors of friends and peers of students involved in bullying. Over the years, scholars have recognized the salience of interventions involving children who are bystanders or witnesses in bullying situations (Polanin et al., 2012). Findings from our study also suggest that bystander interventions are of critical importance to students. Considering that bullying is a group phenomenon, practitioners in school settings are strongly urged to work with schools to help increase bystanders’ actions in bullying situations, and one way to do so is to increase bystanders’ involvement in the existing bullying prevention programs (Polanin et al., 2012).

To decrease moral disengagement, teachers might consider using children’s storybooks with bullying situations, and following them up with classroom discussion. By asking questions, teachers can help the students to be aware of, question, and reject each mechanism of moral disengagement in relation to aggression and bullying (Tolmatcheff et al., 2022; Wang & Goldberg, 2017). Students can also work with hypothetical stories in which they are asked to identify moral disengagement mechanisms, write individual reflections by identifying and describing recent cases in which they had done something they knew were wrong, describe their feelings and use of moral disengagement mechanisms, and then brainstorm in pairs or groups to identify alternatives they could have used instead of the moral disengagement mechanisms (Bustamante & Chaux, 2014). Introducing students to a cartoon storyline of children or teenagers experiencing real-life situations and problems might also be a way of addressing moral disengagement (Newton et al., 2014).

Finally, a study from Thornberg et al. (2018b) found that classrooms with warmer and more caring and supportive student–teacher relationships tended to have a better social climate among students in the classroom in terms of care, warmth, and supportiveness, which in turn was associated with less moral disengagement among students. Both greater student–student relationship quality and moral disengagement at the classroom level were, in turn, linked with fewer bullying victims. Thus, their findings suggest that teachers who establish and maintain positive, supportive, and caring relationships with their students, and together with them make efforts to develop a caring, warm, and supportive classroom climate may counteract moral disengagement, which seems to prevent bullying altogether. Positive student–teacher relationships provide models for caring, responsive, and respectful norms and behavior. Students will be more inclined to listen to and cooperate with teachers who they perceive to be warm, caring, and supportive, and internalize their norms and expectations out of respect in order to maintain these positive relationships (Bear, 2020). In addition, a warm, caring, respectful, and supportive social climate among students would provide caring and prosocial peer models, reinforce high interpersonal moral standards, and offer less space for moral disengagement to grow, as it would conflict with and be counteracted by the social climate.

References

Bandura, A. (2016). Moral disengagement: How people do harm and live with themselves. Worth.

Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(3), 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0303_3

Bear, G. G. (2020). Improving school climate. Routledge.

Bentler, P. M. (1995). EQS structural equations program manual. Multivariate Software

Bjärehed, M., Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., & Gini, G. (2020). Mechanisms of moral disengagement and their associations with indirect bullying, direct bullying, and pro-aggressive bystander behavior. Journal of Early Adolescence, 40(1), 28–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431618824745

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford Press.

Bussey, K. (2020). Development of moral disengagement: Learning to make wrong right. In L. A. Jensen (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of moral development: An interdisciplinary perspective (pp. 306–326). Oxford University Press.

Bussey, K., Luo, A., Fitzpatrick, S., & Allison, K. (2020). Defending victims of cyberbullying: The role of self-efficacy and moral disengagement. Journal of School Psychology, 78, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2019.11.006

Bustamante, A., & Chaux, E. (2014). Reducing moral disengagement mechanisms: A comparison of two interventions. Journal of Latino/Latin American Studies, 6(1), 52–63. https://doi.org/10.18085/llas.6.1.123583644qq115t3

Caravita, S. C. S., Blasio, P. D., & Salmivalli, C. (2009). Unique and interactive effects of empathy and social status on involvement in bullying. Social Development, 18(1), 140–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00465.x

Caravita, S. C. S., Blasio, P. D., & Salmivalli, C. (2010). Early adolescents’ participation in bullying: Is ToM involved? Journal of Early Adolescence, 30(1), 138–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431609342983

Caravita, S. C., Gini, G., & Pozzoli, T. (2012). Main and moderated effects of moral cognition and status on bullying and defending. Aggressive Behavior, 38(6), 456–468. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21447

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum.

Craig, W. M., Pepler, D., & Atlas, R. (2000). Observations of bullying in the playground and in the classroom. School Psychology International, 21(1), 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034300211002

Curren, R., & Ryan, R. M. (2020). Moral self-determination: The nature, existence, and formation of moral motivation. Journal of Moral Education, 49(3), 295–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2020.1793744

Doramajian, C., & Bukowski, W. M. (2015). A longitudinal study of the associations between moral disengagement and active defending versus passive bystanding during bullying situations. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 61(1), 144–172. https://doi.org/10.13110/merrpalmquar1982.61.1.0144

Forsberg, C., Thornberg, R., & Samuelsson, M. (2014). Bystanders to bullying: Fourth-to seventh-grade students’ perspectives on their reactions. Research Papers in Education, 29(5), 557–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2013.878375

Forsberg, C., Wood, L., Smith, J., Varjas, K., Meyers, J., Jungert, T., & Thornberg, R. (2018). Students’ views on factors affecting their bystander acts in bullying situations: A cross-collaborative conceptual qualitative analysis. Research Papers in Education, 3(1), 127–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2016.1271001

Friends (2022). Mobbningens förekomst: Tre barn utsatta i varje klass [The presence of bullying: Three children in each class]. Friends.

Gini, G. (2006). Social cognition and moral cognition in bullying: What’s wrong? Aggressive Behavior, 32(6), 528–539. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20153

Gini, G., Pozzoli, T., & Bussey, K. (2015). The role of individual and collective moral disengagement in peer aggression and bystanding: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(3), 441–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9920-7

Gini, G., Pozzoli, T., & Hymel, S. (2014). Moral disengagement among children and youth: A meta-analytic review of links to aggressive behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 40(1), 56–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21502

Hardy, S. A., Dollahite, D. C., Johnson, N., & Christensen, J. B. (2015). Adolescent motivations to engage in pro-social behaviors and abstain from health-risk behaviors: A self-determination theory approach. Journal of Personality, 83(5), 479–490. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12123

Hymel, S., McClure, R., Miller, M., Shumka, E., & Trach, J. (2015). Addressing school bullying: Insights from theories of group processes. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 37, 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2014.11.008

Jamovi Project (2019). Jamovi (Version 1.0) [Computer Software]. Retrieved from https://www.jamovi.org.

Jiang, S., Liu, R.-D., Ding, Y., Jiang, R., Fu, X., & Hong, W. (2022). Why the victims of bullying are more likely to avoid involvement when witnessing bullying situations: Sensitivity and moral disengagement. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(5–6), NP3062–NP3083. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520948142

Jungert, T., Dubord, M.-C.G., Högberg, M., & Forest, J. (2022). Can managers be trained to further support their employees’ basic needs and work engagement: A manager training program study. International Journal of Training and Development, 26(3), 472–494. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijtd.12267

Jungert, T., Landry, R., Joussemet, M., Mageau, G., Gingras, I., & Koestner, R. (2015). Autonomous and controlled motivation for parenting: Associations with parent and child outcomes. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(7), 1932–1942. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-9993-5

Jungert, T., & Perrin, S. (2019). Trait anxiety and bystander motivation to defend victims of school bullying. Journal of Adolescence, 77(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.10.001

Jungert, T., Piroddi, B., & Thornberg, R. (2016). Early adolescents’ motivations to defend victims in school bullying and their perceptions of student-teacher relationships: A self-determination theory approach. Journal of Adolescence, 53(1), 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.09.001

Kärnä, A., Voeten, M., Poskiparta, E., & Salmivalli, C. (2010). Vulnerable children in different classrooms: Classroom-level factors moderate the effect of individual risk on victimization. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 56(2), 261–282. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.0.0052

Killer, B., Bussey, K., Hawes, D. J., & Hunt, C. (2019). A meta-analysis of the relationship between moral disengagement and bullying roles in youth. Aggressive Behavior, 45(4), 450–462. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21833

Levasseur, C., Desbiens, N., & Bowen, F. (2017). Moral reasoning about school bullying in involved adolescents. Journal of Moral Education, 46(2), 158–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2016.1268113

Longobardi, C., Borello, L., Thornberg, R., & Settanni, M. (2020). Empathy and defending behaviours in school bullying: The mediating role of motivation to defend victims. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(2), 473–486. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12289

Mazzone, A., Camodeca, M., & Salmivalli, C. (2016). Interactive effects of guilt and moral disengagement on bullying, defending and outsider behavior. Journal of Moral Education, 45(4), 419–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2016.1216399

Mischel, J., & Kitsantas, A. (2020). Middle school students’ perceptions of school climate, bullying prevalence, and social support and coping. Social Psychology of Education, 23(1), 51–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-019-09522-5

Moran, C. M., Diefendorff, J. M., Kim, T.-Y., & Liu, Z.-Q. (2012). A profile approach to self-determination theory motivations at work. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81(3), 354–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.09.002

Newton, N. C., Andrews, G., Champion, K. E., & Teesson, M. (2014). Universal Internet-based prevention for alcohol and cannabis use reduces truancy, psychological distress and moral disengagement: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Preventive Medicine, 65, 109–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.05.003

Ng, J. Y., Ntoumanis, N., Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C., Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Duda, J. L., & Williams, G. C. (2012). Self-determination theory applied to health contexts: A meta-analysis. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(4), 325–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612447309

Niemiec, C. P., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom: Applying self-determination theory to educational practice. Theory and Research in Education, 7(2), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878509104318

Nocentini, A., Menesini, E., & Salmivalli, C. (2013). Level and change of bullying behavior during high school: A multilevel growth curve analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 36(3), 495–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.02.004

Nucci, L. P. (2001). Education in the moral domain. Cambridge University Press.

O’Connell, P., Pepler, D., & Craig, W. (1999). Peer involvement in bullying: Insights and challenges for observation. Journal of Adolescence, 22(4), 437–452. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.1999.0238

Peeters, W., Diependaele, L., & Sterckx, S. (2019). Moral disengagement and the motivational gap in climate change. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 22(2), 425–447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-019-09995-5

Polanin, J. R., Espelage, D. L., & Pigott, T. D. (2012). A meta-analysis of school-based bullying prevention programs’ effects on bystander intervention behavior. School Psychology Review, 41(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2012.12087375

Pouwels, J. L., Lansu, T. A. M., & Cillessen, A. H. N. (2016). Participant roles of bullying in adolescence: Status characteristics, social behavior, and assignment criteria. Aggressive Behavior, 42(3), 239–253. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21614

Pouwels, J. L., Lansu, T. A. M., & Cillessen, A. H. N. (2018). A developmental perspective on popularity and the group process of bullying. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 43, 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.10.003

Pöyhönen, V., Juvonen, J., & Salmivalli, C. (2010). What does it take to stand up for the victim of bullying? The interplay between personal and social factors. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 56(2), 143–163. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.0.0046

Pozzoli, T., Gini, G., & Thornberg, R. (2016). Bullying and defending behavior: The role of explicit and implicit moral cognition. Journal of School Psychology, 59, 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2016.09.005

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Publications.

Saarento, S., Garandeau, C. F., & Salmivalli, C. (2015). Classroom- and school-level contributions to bullying and victimization: A review. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 25(3), 204–218. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2207

Salmivalli, C. (2010). Bullying and the peer group: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15(2), 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.08.007

Salmivalli, C., Voeten, M., & Poskiparta, E. (2011). Bystanders matter: Associations between reinforcing, defending, and the frequency of bullying in classrooms. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 40(5), 668–676. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2011.597090

Sjögren, B., Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., & Gini, G. (2021a). Associations between students’ bystander behavior and individual and classroom collective moral disengagement. Educational Psychology, 41(3), 264–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2020.1828832

Sjögren, B., Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., & Gini, G. (2021b). Bystander behaviour in peer victimisation: Moral disengagement, defender self-efficacy and student-teacher relationship quality. Research Papers in Education, 36(5), 588–610. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2020.1723679

Strindberg, J., Horton, P., & Thornberg, R. (2020). The fear of being singled out: Pupils’ perspectives on victimisation and bystanding in bullying situations. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 41(7), 942–957. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2020.1789846

Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (2018). Skolundersökningen om brott 2017: Om utsatthet och delaktighet i brott [The national survey of violations 2017: Victimization and involvement in crime] (Report 2018:15). Brottsförebyggande Rådet.

Taylor, G., Jungert, T., Mageau, G. A., Schattke, K., Dedic, H., Rosenfield, S., & Koestner, R. (2014). A self-determination theory approach to predicting school achievement over time: The unique role of intrinsic motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 39(4), 342–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.08.002

Thornberg, R., & Jungert, T. (2013). Bystander behavior in bullying situations: Basic moral sensitivity, moral disengagement and defender self-efficacy. Journal of Adolescence, 36(3), 475–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.02.003

Thornberg, R., Landgren, L., & Wiman, E. (2018a). ‘It depends’: A qualitative study on how adolescent students explain bystander intervention and non-intervention in bullying situations. School Psychology International, 39(4), 400–415. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034318779225

Thornberg, R., Pozzoli, T., Gini, G., & Hong, J. S. (2017a). Bullying and repeated conventional transgressions in Swedish schools: How do gender and bullying roles affect students’ conceptions? Psychology in the Schools, 54(9), 1189–1201. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22054

Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., Elmelid, R., Johansson, A., & Mellander, E. (2020). Standing up for the victim or supporting the bully? Bystander responses and their associations with moral disengagement, defender self-efficacy, and collective efficacy. Social Psychology of Education, 23(3), 563–581. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-020-09549-z

Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., Hong, J. S., & Espelage, D. L. (2017b). Classroom relationship qualities and social-cognitive correlates of defending and passive bystanding in school bullying in Sweden: A multilevel analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 63, 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2017.03.002

Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., Pozzoli, T., & Gini, G. (2018b). Victim prevalence in bullying and its association with teacher-student and student-student relationships and class moral disengagement: A class-level path analysis. Research Papers in Education, 33(3), 320–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2017.1302499

Tolmatcheff, C., Galand, B., Roskam, I., & Veenstra, R. (2022). The effectiveness of moral disengagement and social norms as anti-bullying components: A randomized controlled trial. Child Development, 93(6), 1873–1888. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13828

van Goethem, A. J. A., Scholte, R. H. J., & Wiers, R. W. (2010). Explicit- and implicit bullying attitudes in relation to bullying behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(6), 829–842. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9405-2

Wang, C., & Goldberg, T. S. (2017). Using children’s literature to decrease moral disengagement and victimization among elementary school students. Psychology in the Schools, 54(9), 918–931. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22042

Funding

Open access funding provided by Linköping University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thornberg, R., Jungert, T. & Hong, J.S. The indirect association between moral disengagement and bystander behaviors in school bullying through motivation: Structural equation modelling and mediation analysis. Soc Psychol Educ 26, 533–556 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-022-09754-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-022-09754-y