Abstract

The newly identified severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) causes COVID-19, a pandemic respiratory disease. Moreover, thromboembolic events throughout the body, including in the CNS, have been described. Given the neurological symptoms observed in a large majority of individuals with COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2 penetrance of the CNS is likely. By various means, we demonstrate the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA and protein in anatomically distinct regions of the nasopharynx and brain. Furthermore, we describe the morphological changes associated with infection such as thromboembolic ischemic infarction of the CNS and present evidence of SARS-CoV-2 neurotropism. SARS-CoV-2 can enter the nervous system by crossing the neural–mucosal interface in olfactory mucosa, exploiting the close vicinity of olfactory mucosal, endothelial and nervous tissue, including delicate olfactory and sensory nerve endings. Subsequently, SARS-CoV-2 appears to follow neuroanatomical structures, penetrating defined neuroanatomical areas including the primary respiratory and cardiovascular control center in the medulla oblongata.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

There is increasing evidence that SARS-CoV-2 not only affects the respiratory tract but also impacts the CNS, resulting in neurological symptoms such as loss of smell and taste, headache, fatigue, nausea and vomiting in more than one-third of individuals with COVID-19 (refs. 1,2). Moreover, acute cerebrovascular disease and impaired consciousness have been reported3. While recent studies have described the presence of viral RNA in the brain and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), they have lacked proof of genuine SARS-CoV-2 infection4,5. A systematic analysis of autopsy brains and peripheral tissues aimed at understanding the port of entry and distribution for SARS-CoV-2 within the CNS has therefore been missing6.

Currently, there are seven types of coronavirus (CoV) that naturally infect humans7,8, and, of these, at least two endemic strains have been shown to enter and persist in the CNS. In one autopsy study, 48% of the investigated cases carried detectable human CoV RNA in the CNS9. Additionally, the neuroinvasive potential of SARS‐CoV and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)-CoV, which are evolutionarily closely related to SARS-CoV-2, has previously been described10,11,12.

SARS-CoV, including SARS-CoV-2, are known to enter human host cells primarily by binding to the cellular receptor angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and by the action of the serine protease TMPRSS2 for spike (S) protein priming13. Supporting evidence comes from animal studies demonstrating that SARS‐CoV is capable of entering the brain upon intranasal infection of mice expressing human ACE2 (refs. 12,14). In the lung, bronchial transient secretory cells express ACE2 and TMPRSS2 (ref. 15). Similarly, there is evidence for ACE2 expression in neuronal and glial cells in the human CNS16. In human olfactory mucosa, ACE2 was shown to be expressed by non-neuronal cells under physiological conditions17, while little is known about ACE2 expression in an inflammatory or septic setting18.

Because knowledge of SARS-CoV-2 neurotropism and potential mechanisms of CNS entry and viral distribution is key for a better understanding of COVID-19 diagnosis, prognosis and interventional measures, we assessed olfactory mucosa, its nervous projections and several defined CNS regions in 33 individuals who died in the context of COVID-19.

Results

We analyzed the cellular mucosal–nervous micromilieu as a first site of viral infection and replication, followed by thorough regional mapping of the consecutive olfactory nervous tracts and defined CNS regions, in autopsy material from 33 individuals with COVID-19 (n = 22 male and n = 11 female) examined between March and August of 2020 (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). The median age at death was 71.6 years (interquartile range, 67–79 years; range, 30 to 98 years), and the time from onset of COVID-19 symptoms to death ranged from 4 to 79 days, with a median of 31 days. Cases were not preselected with regard to clinical and/or neurological symptoms, which, owing to the pandemic situation, in some instances were not fully documented or not possible to retrieve. Clinically documented COVID-19-associated neurological alterations included impaired consciousness (n = 5), intraventricular hemorrhage (n = 2), headache (n = 2) and behavioral changes (n = 2); acute cerebral ischemia was reported for 2 individuals, while neuropathological postmortem workup revealed acute infarcts in 6 individuals (Supplementary Table 2). Coexisting conditions included diabetes mellitus (n = 4), hypertension (n = 21), cardiovascular disease (n = 9), hyperlipidemia (n = 2), chronic kidney disease (n = 2), prior stroke (n = 6) and dementia (n = 5) (Supplementary Table 1). Although all 33 individuals required mechanical ventilation and at the time of autopsy were found to have suffered from COVID-19-associated lung disease, 9 did not receive mechanical ventilation according to the will of the respective individual. Additional clinical information on comorbidities is provided in Supplementary Table 1. Thirty-one individuals were proven to be positive by quantitative PCR with reverse transcription (RT–qPCR) for SARS-CoV-2 before death (n = 31 of 33), while 2 individuals showed a clinical presentation highly suggestive of COVID-19 (n = 2 of 33). Correspondingly, ACE2 was detectable in olfactory mucosa by means of immunohistochemistry, while we found no reliable ACE2 immunoreactivity in the parenchyma of the CNS, namely, in the olfactory bulb and medulla oblongata (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Regional mapping of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in olfactory mucosa, its nervous projections and distinct CNS regions

Assessment of viral load by means of RT–qPCR in regionally defined tissue samples including the olfactory mucosa (R1), olfactory bulb (R2), olfactory tubercle (R3), oral mucosa (uvula; R4), trigeminal ganglion (R5), medulla oblongata (R6) and cerebellum (R7) demonstrated the highest levels of viral RNA for SARS-CoV-2 within the olfactory mucosa sampled directly beneath the cribriform plate (n = 20 of 30; Fig. 1a). Lower levels of viral RNA were found in the cornea, conjunctiva and oral mucosa, highlighting the oral and ophthalmic routes as additional potential sites of SARS-CoV-2 CNS entry (Fig. 1b–d). In only a few COVID-19 autopsy cases, the cerebellum (n = 3 of 24) was positive for SARS-CoV-2 by means of RT–qPCR. The carotid artery wall served as a control tissue for excluding or proving systemic (vascular) entry routes to the CNS and was found to be negative in 12 of the 13 samples analyzed; the one positive result was derived from the carotid artery of an individual with acute COVID-19 disease. Subgenomic RNA (sgRNA) is used as a surrogate for active viral replication. We obtained a positive result in 4 of 20 olfactory mucosa samples positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA and 1 of 6 uvula samples positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA, but in none of the other tissues analyzed in this study (Fig. 1b–d and Supplementary Table 2). Disease duration inversely correlated with the amount of detectable SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the CNS, with high SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels found in individuals with COVID-19 who had relatively short disease duration, whereas individuals with prolonged COVID-19 disease typically had low RNA load (correlation coefficient r = −0.5, **P = 0.006 from n = 29 individuals; Fig. 1e).

a, Cartoon depicting the anatomical structures sampled for histomorphological, ultrastructural and molecular analyses including SARS-CoV-2 RNA measurement from fresh (non-formalin-fixed) specimens of deceased individuals with COVID-19. Specimens were taken from the olfactory mucosa underneath the cribriform plate (anatomical region R1, blue, n = 30), the olfactory bulb (R2, yellow, n = 31), the olfactory tubercle (R3, n = 7), different branches of the trigeminal nerve (including conjunctiva (n = 16) and cornea (n = 13)), mucosa covering the uvula (R4, n = 22), the respective trigeminal ganglion (R5, orange, n = 22), the cranial nerve nuclei in the medulla oblongata (R6, dark blue, n = 31), the cerebellum (R7, n = 24) and the carotid artery wall (n = 13). b–d, Quantitative data for each individual shown on a logarithmic scale normalized on 10,000 cells. e, Correlation of disease duration and viral RNA load in the CNS (typically measured in the olfactory bulb or medulla oblongata). The length of disease duration correlates inversely with the amount of detectable SARS-CoV-2 RNA (correlation coefficient r = −0.5, **P = 0.006 from n = 29 individuals). Females are represented by triangles and males are represented by circles; no data for P27 is shown because no viral testing could be performed on naive or cryopreserved tissue of P27.

The olfactory mucosal–nervous milieu as a SARS-CoV-2 CNS entry-prone interface

Anatomical proximity of neurons, nerve fibers and mucosa within the oro- and nasopharynx (Fig. 2a–f) and the reported clinical–neurological signs related to alterations in smell and taste perception suggest that SARS-CoV-2 exploits this neural–mucosal interface as a port of entry into the CNS. The olfactory epithelium is organized as a pseudostratified epithelial structure mainly composed of olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs), apical sustentacular cells, Bowman’s gland (BG), microvillous cells and neural stem cells19. Horizontal basal cells (HBCs) and globose basal cells (GBCs) complete the spectrum of immature and mature neural/neuronal cells20,21. On the apical side of the olfactory mucosa, the dendrites of OSNs project into the nasal cavity, while on the basal side the axons of OSNs merge into fila, which protrude through the cribriform plate directly into the olfactory bulb (Fig. 2), thereby also having contact with CSF22. OSNs are bipolar cells, and somatic (including dendritic and axonal) expression of olfactory membrane protein (OMP) indicates their mature state (Fig. 2g), while expression of class III β-tubulin (TuJ1) corresponds to both immature and mature neuronal cells within the olfactory mucosa20 (Fig. 2h). The neuronal cells coalesce with the other cells to the epithelial layer.

a–c, Cartoon (a) and histopathological coronal cross-sections (b,c; individual P9) depicting the paranasal sinus region with the osseous cribriform plate (turquoise asterisk and dotted line in b; pink asterisk and dotted line in c) and the close anatomical proximity of the olfactory mucosa (green in b, purple in c) and nervous tissue characterized by nerve fibers immunoreactive for S100 protein (c, brown). d, Cartoon representing the olfactory mucosa, which is composed of pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium (asterisk), basement membrane and lamina propria and also contains mucus-secreting BGs and bipolar OSNs, which coalesce to the epithelial layer. e,f, Immunohistochemical staining of the olfactory mucosa showing epithelial cells (e, immunoreactivity for the pan-cytokeratin marker AE1/AE3, red, individual P9), which closely intermingle with staining for OLIG2 specifying late neuronal progenitor cells and newly formed neurons (f, nuclear staining, brown, individual P27)45. In e, the basement membrane underneath the columnar AE1/AE3-positive epithelium is discontinued due to CD56-positive (brown) nerve fibers of either olfactory or trigeminal origin (arrow). g, Cell bodies (arrows) and dendrites (arrowheads) of OMP-positive mature OSNs (brown, control individual C6 without COVID-19) are shown. h, Immunostaining for TuJ1 corresponding to both immature and mature neural/neuronal cells and their dendrites (brown, control individual C6 without COVID-19). Scale bars: 0.5 cm (b,c), 30 µm (e,g,h) and 50 µm (f).

SARS-CoV-2 tropism within the olfactory mucosa

When assessing the local distribution of SARS-CoV-2 within SARS-CoV-2 PCR-positive tissue at the cellular level, we found that SARS-CoV S protein was most prevalent in the olfactory mucosa. Using immunohistochemistry, distinct immunoreactivity for SARS-CoV S protein, including a characteristic granular, partly perinuclear pattern, was found in morphologically distinct cell types indicative of neuronal/neural origin (Fig. 3a). SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detectable in cells of the olfactory epithelium and in olfactory mucus by RNAScope in situ hybridization (ISH) in formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples (Fig. 3b). On the ultrastructural level, we were able to detect intact CoV particles in an individual with high viral RNA load and presence of sgRNA (Fig. 3c–f). Re-embedding of FFPE olfactory mucosa for electron microscopy (EM) allowed selective assessment of a tissue region with a strong SARS-CoV-2 RNA ISH signal (Fig. 3b). Characteristic CoV substructures within the respective cellular compartments were found as expected, including surface projections (spikes) and partially visible membrane envelope as well as a heterogeneous and partly granular electron-dense interior due to the presence of ribonucleoprotein (RNP). Only subtle ultrastructural differences as compared to CoV-infected cell cultures were noted. These were clearly discernible from intrinsic cellular structures or artifacts and can be entirely explained by the FFPE re-embedding procedure23,24,25,26,27,28 (Supplementary Fig. 2).

a, CoV antigen detected by anti-SARS-CoV S protein antibodies (brown, individual P30) exhibits a cytoplasmic, often perinuclear, signal for CoV-positive cells resembling epithelial cells and cells harboring dendrite-like projections (arrowhead) with tips (arrows), which morphologically qualify as OSNs. b, SARS-CoV-2 RNA ISH showing intense signals in the mucus layer and cells (arrows) of the epithelium (asterisk) (brown, individual P15). c–f, Ultrastructural images of re-embedded FFPE material showing numerous extracellular CoV particles (c, arrows) attached to kinocilia (c, white asterisks) and intracellular CoV particles (d–f, increasing magnification) in a ciliated cell (individual P15, punch biopsy from the area in b). In e and f, intracellular CoV particles are located within cellular compartments of different sizes and are similar in their size and substructure. In f, at high magnification, five particles in this region show a particularly well-recognizable substructure (black arrows) that includes characteristic surface projections (black arrowhead), a heterogeneous and partly granular electron-dense interior, most likely representing RNP (white arrowheads), and a membrane envelope (white arrows). Scale bars: 20 µm (a), 50 µm (b), 1 µm (c), 2 µm (d), 500 nm (e) and 200 nm (f).

To further pinpoint which cells within the olfactory mucosa harbor SARS-CoV-2, we performed colocalization studies using various neuronal markers and SARS-CoV S protein, finding perinuclear SARS-CoV S protein immunoreactivity in TuJ1+ (Fig. 4a–d), neurofilament 200 (NF200)+ (Fig. 4e–h) and OMP+ (Fig. 4i–l) neural/neuronal cells in three individuals with COVID-19 where adequate tissue for this type of analysis was available; olfactory mucosa from two individuals without COVID-19 was used as a negative control and showed no immunoreactivity for SARS-CoV S protein in otherwise equally detectable TuJ1+ or OMP+ neural/neuronal cells (Supplementary Fig. 3g,h).

a–l, Representative maximum-intensity projections of confocal (a–d and i–l) or epifluorescence (e–h) microscopy images of olfactory mucosa showing intracytoplasmic staining for SARS-CoV S protein within TuJ1+ (a–d, individual P27), NF200+ (e–h, individual P27) and OMP+ (i–l, individual P27) OSNs. Staining for TuJ1, NF200 and OMP (magenta, Alexa Fluor 488) marks cells of neuronal origin, staining for SARS-CoV S protein (yellow, Alexa Fluor 555) visualizes the presence of SARS-CoV and DAPI staining (petrol) identifies all cell nuclei (n = 3 individuals with COVID-19 (P27, P30 and P32) were analyzed; n = 2 individuals without COVID-19 served as controls; shown are representative images from P27). Scale bars, (all panels) 10 µm.

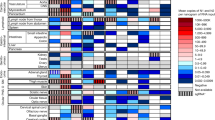

The results of the different approaches used to detect SARS-CoV-2 including SARS-CoV S immunostaining, ISH for SARS-CoV-2 RNA and ultrastructural analyses to visualize CoV particles at various sites and regions are summarized in a heatmap-like manner (Fig. 5), ultimately supporting the hypothesis of a site-specific, local CNS infection by SARS-CoV-2.

Various SARS-CoV-related investigations of the individuals who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by RT–qPCR in the olfactory mucosa (OM), the CNS or both. SARS-CoV-2 RT–qPCR positivity was combined with results derived from SARS-CoV-specific immunohistochemistry (IHC) and ISH as well as EM in appropriate tissue as available.

The SARS-CoV-2-mediated neuroinflammatory response

As an indirect sign of local infection and ongoing inflammation, we looked for small cell clusters of early activated macrophages expressing myeloid-related protein 14 (MRP14), which were detected in the olfactory epithelium (Supplementary Fig. 1). These cells can initiate and regulate an immune cascade that, upon influenza virus infection, has been shown to act as an endogenous damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP), ultimately initiating a virus-associated inflammatory response via TLR4–MyD88 signaling29. In the CNS, we found strong upregulation of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DR on microglia/macrophages, which were often arranged in so-called microglial nodules, in 13 of 25 individuals analyzed (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 4b–f). There was no evidence of MRP14+ cells nor of infiltrating lymphomonocytic cells within the CNS. A correlate of this HLA-DR-positive, presumably myeloid-driven inflammatory response was found in the CSF, where levels of inflammatory mediators such as interleukin (IL)-6, IL-18, CC-chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM-1) were found to be increased (Supplementary Fig. 4a)30.

Cerebral microthrombosis and acute CNS infarcts

In line with recent clinical data demonstrating thromboembolic CNS events in a few individuals with COVID-19 (ref. 31), we found in 18% of the 33 individuals investigated (n = 6 of 33) a histopathological correlate of microthrombosis and subsequent acute territorial brain infarcts (Fig. 6a–c and Supplementary Table 2). Of note, there was increased immunoreactivity to SARS-CoV S protein (which is thought to also recognize other CoV types) in endothelial cells within these acute cerebral infarcts (Fig. 6b,c) in comparison to a weaker but similarly distributed endothelial staining pattern in some control individuals (Supplementary Fig. 5). Because of the limitations in obtaining accessible and appropriate frozen, unfixed CNS tissue from these acute infarcts, we were only able to assess an infarct located within the medulla oblongata in one individual (P3) by means of RT–qPCR, finding that this sample was positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA. As shown for the CNS, microthromboembolic events were also detectable in the olfactory mucosa in one individual.

a, Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained FFPE section of the thalamus obtained from a deceased individual with COVID-19 (individual P26). Several small vessels exhibit fresh thrombi (pink, indicated by arrows) resulting in a large infarct of surrounding CNS tissue characterized by a substantial reduction of detectable neuronal and glial nuclei, edema and vacuolation. b,c, SARS-CoV S protein observed in the endothelial cells of small CNS vessels. Tissue with no obvious ischemic damage exhibits only sparse staining intensity in endothelial cells (b, medulla oblongata, n = 3 of 6; red, indicated by arrows, individual P3) when compared to endothelial cells within acute infarct areas (c, pons, n = 3 of 4; red, indicated by arrows, individual P4; inset depicts a magnified vessel from a different region of the same specimen exhibiting SARS-CoV S protein deposits within endothelial cells). Scale bars: 30 µm (a), 50 µm (b), 200 µm (c) and 40 µm (inset in c).

Discussion

Several recent tissue-based studies assessing CNS alterations in fatal COVID-19 have provided the first hints at histopathological changes occurring in COVID-19 such as hypoxia-related pathology including CNS infarction due to cerebral thromboembolism and signs of a CNS-intrinsic myeloid cell response32,33,34,35,36,37,38 and/or have presented data on the presence of viral RNA in the CNS4,39. To extend existing knowledge and to provide further proof for the presence and distribution of SARS-CoV-2 in the olfactory mucosa and within the CNS, we visualized viral RNA and protein using ISH and immunohistochemical staining techniques. This allowed us to dissect the cells harboring the virus and shed light on the mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 CNS entry at the neural–mucosal interface in olfactory mucosa. We were also able to visualize intact CoV particles at the ultrastructural level. Such data are often misinterpreted40, especially when conclusions are solely based on relatively ill-defined virus-like substructures41. In tissues positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA, we found SARS-CoV S protein in the cytoplasm of endothelial cells, in contrast to the findings of Solomon et al.38; the different results are most likely due to methodological differences between the staining protocols used. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the CNS was found to result in a local CNS response mediated through HLA-DR+ microglia as effectors of a myeloid-driven inflammatory response. This innate immune response has a correlate in the CSF, where the levels of inflammatory mediators were found to be increased.

Presence of intact CoV particles together with SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the olfactory mucosa, as well as in neuroanatomical areas receiving olfactory tract projections (Fig. 1b), may suggest SARS-CoV-2 neuroinvasion occurring via axonal transport. However, morphological detection of single viral particles in axons is (if possible at all) very difficult owing to the very low number of viral particles that are expected, given that the viral reproduction apparatus is thought to be located in the neuronal somata. This difficulty in visualizing SARS-CoV-2 within the CNS on a cellular level is further aggravated by the fact that the olfactory bulb is a relatively small CNS region with a limited number of neurons, which is evidenced by the small amount of viral RNA that was obtained in COVID-19 cases harboring SARS-CoV-2 PCR-positive olfactory bulbs. In addition, the ability to detect SARS-CoV-2 may also be affected by the duration of COVID-19 infection, as the duration determines the viral load at a given time point and location, and we cannot exclude the possibility that virus-infected (neuronal) cells might die and thus evade detection.

As we were able to detect SARS-CoV-2 RNA in some individuals in CNS regions that have no direct connection to the olfactory mucosa, such as the cerebellum, there may be other mechanisms or routes of viral entry into the CNS, possibly in addition to or in combination with axonal transport. For instance, migration of SARS-CoV-2-carrying leukocytes across the blood–brain barrier (BBB) or viral entry along CNS endothelia cannot be excluded. The latter is a valid possibility, at least in addition to a presumably axonal route, as we found immunoreactivity to SARS-CoV S protein in cerebral and leptomeningeal endothelial cells (Fig. 6b,c and Supplementary Fig. 5).

Widespread dysregulation of the cardiovascular, pulmonary and renal systems has been thought to be a leading cause of disease in severe or lethal COVID-19 cases42. In light of previous reports of infection by SARS-CoV and other CoVs in the nervous system43 and our observations of SARS-CoV-2 in the brainstem, which comprises the primary respiratory and cardiovascular control center, it is possible that SARS-CoV-2 infection, at least in some instances, might aggravate respiratory or cardiac insufficiency—or even cause failure—in a CNS-mediated manner44. The presence of acute infarcts in the brainstem (n = 2 of 6 individuals analyzed; Supplementary Table 2) might support this notion. Even in the absence of clear signs of widespread distribution of SARS-CoV-2 in neuronal or glial cells of the CNS parenchyma in the COVID-19 autopsy cases investigated here, SARS-CoV-2 in the CNS endothelium might facilitate vascular damage and allow the virus to spread more widely to other brain regions over time, thus eventually contributing to a more severe or even chronic disease course, depending on various factors such as the duration of viral persistence, viral load and immune status, among others.

Taking our findings together, we provide evidence that SARS-CoV-2 neuroinvasion can occur at the neural–mucosal interface by transmucosal entry via regional nervous structures. This may be followed by transport along the olfactory tract of the CNS, thus explaining some of the well-documented neurological symptoms in COVID-19, including alterations of smell and taste perception. One caveat to note with the COVID-19 cases reported here is the relatively long postmortem interval, an almost insurmountable obstacle in autopsy studies, especially when performed under the emergency-like conditions encountered during a pandemic situation. Analysis of these samples is limited by well-known restrictions resulting from autolysis of cells and tissues, ultimately complicating the interpretation of morphological and molecular analyses. In spite of these limitations, we were able to retrieve numerous valuable insights. These included the detection of well-preserved CoV particles at the ultrastructural level in an individual with an 82-hour postmortem interval (P15) and important pathogenetic insights, thus enabling further, more detailed and mechanistic investigations while encouraging further autopsy studies including broad sampling to allow multiple complementary analyses and the application of state-of-the-art methodologies. Such studies will allow identification of the precise cellular and molecular SARS-CoV-2 entry mechanism as well as receptors on OSNs, where non-neuronal pathways may also have a role17.

Methods

Study design

Thirty-three deceased individuals with COVID-19 either confirmed by PCR for SARS-CoV-2 (n = 31 of 33) or with clinical features highly suggestive of COVID-19 (n = 2 of 33) were included (Supplementary Table 1). Individuals were not preselected with regard to their clinical symptoms. Autopsies were performed at the Department of Neuropathology and the Institute of Pathology, Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin (n = 25 of 33), including one referral from the Institute of Pathology, DRK Kliniken Berlin, the Institutes of Pathology and of Neuropathology, University Medical Center Göttingen (n = 6 of 33) and the Institute of Forensic Medicine, Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin (n = 1 of 33). This study was approved by the local ethics committees (Berlin: EA1/144/13, EA2/066/20 and EA1/075/19; Göttingen: 42/8/20) as well as by the Charité–BIH COVID-19 research board and was in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki; autopsies were performed on the legal basis of §1 of the Autopsy Act of the state Berlin and §25(4) of the German Infection Protection Act. In all deceased individuals, a whole-body autopsy was performed, which included a thorough histopathological and molecular evaluation comprising virological assessment of SARS-CoV-2 RNA and/or SARS-CoV S protein levels in the carotid artery, cornea, conjunctiva, optic nerve, uvula, olfactory mucosa, olfactory bulb, olfactory tract, trigeminal ganglion, medulla oblongata and cerebellum as indicated in Supplementary Table 2. To exclude cross-contamination, clean instruments for the preparation and sampling of each organ and region were always used. All individuals with COVID-19 with known disease duration and available PCR-tested appropriate CNS tissue were included (n = 29 of 33) to calculate the correlation coefficient for the correlation between disease duration and CNS SARS-CoV-2 viral load. Therefore, we could not perform randomization as all individuals with SARS-CoV-2 RNA were included in the COVID-19 group and controls were defined as individuals negative for SARS-CoV-2 by PCR. Where available, clinical records were assessed thoroughly for preexisting medical conditions and medications and progression of the disease as well as COVID-19-related symptoms before death, with a special focus on neurological symptoms including alterations in olfaction and taste.

SARS-CoV- and SARS-CoV-2-specific PCR including subgenomic RNA assessment

For PCR-based assessment of SARS-CoV-2 RNA, unfixed and, where possible, non-cryopreserved (i.e., native) tissue samples were used. RNA was purified from ∼50 mg of homogenized tissue obtained from all organs by using the MagNAPure 96 system and the MagNAPure 96 DNA and Viral NA Large Volume kit (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantitative real-time PCR for SARS-CoV-2 was performed on RNA extracts with RT–qPCR _targeting the SARS-CoV-2 E gene. Quantification of viral RNA was performed using photometrically quantified in vitro RNA transcripts as described previously46. Total DNA was measured in all extracts by using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The RT–qPCR analysis was replicated at least once for each sample.

Detection of sgRNA, as a correlate of active virus replication in the tested tissue, was performed by using oligonucleotides _targeting the leader transcriptional regulatory sequence and a region within the sgRNA encoding the SARS-CoV-2 E gene, as described previously47.

Histological and immunohistochemical techniques

FFPE tissue blocks were taken at the day of autopsy when the postmortem interval was shorter than 24 h and fixed for 24 h in 4% paraformaldehyde. Otherwise, brain tissue was fixed for 14 d in 4% paraformaldehyde before cutting. Routine histological staining (H&E, Masson–Goldner, periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) reaction and toluidine blue) was performed according to standard procedures. Immunohistochemical staining was performed either on a Benchmark XT autostainer (Ventana Medical Systems) with standard antigen retrieval methods (CC1 buffer, pH 8.0, Ventana Medical Systems) or manually using 1-μm- or 4-μm-thick FFPE tissue sections. The following primary antibodies were used: polyclonal rabbit anti-S100 (Dako, Z0311; 1:3,000), monoclonal mouse anti-AE1/AE3 (Dako, M3515; 1:200), monoclonal mouse anti-MRP14 (Acris, BM4026B; 1:500, pretreatment protease), monoclonal mouse anti-CD56 (Serotec, ERIC-1; 1:200), mouse monoclonal anti-SARS spike glycoprotein (Abcam, ab272420; 1:100), goat anti-OMP (Wako, 019-22291; 1:1,000), rabbit monoclonal anti-βIII tubulin (Abcam, ab215037; 1:2,000), rabbit polyclonal anti-NF200 (Sigma, N4142; 1:100), rabbit polyclonal anti-ACE2 (Proteintech, 21115-1-AP; 1:3,000) and rabbit polyclonal anti-OLIG2 (IBL, 18953; 1:150, pretreatment Tris-EDTA + microwave). Briefly, primary antibodies were applied and developed by using either the iVIEW DAB Detection kit (Ventana Medical Systems) and the ultraView Universal Alkaline Phosphatase Red Detection kit (Ventana Medical Systems) or manual application of biotinylated secondary antibodies (biotinylated donkey anti-sheep-goat (1:200; Amersham, RPN 1025), biotinylated donkey anti-rabbit (1:200), biotinylated sheep anti-mouse (1:200; Amersham, RPN 1001), rabbit immunoglobulin (RPN1004), peroxidase-conjugated avidin and diaminobenzidine (DAB; Sigma, D5637) or 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazol (AEC). Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated in a graded alcohol and xylene series, mounted and coverslipped. Immunohistochemistry sections were evaluated by at least two board-certified neuropathologists with concurrence. To biologically validate all immunohistological staining, control tissues harboring or lacking the expected antigens were used. Staining patterns were compared to expected results as specified in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Fig. 1a–d (ACE2), Supplementary Fig. 5e (SARS-CoV S), Supplementary Fig. 6 (NF200, SARS-CoV S) and Supplementary Fig. 3 (S100, OLIG2, HLA-DR, CD56, CD45, AE1/AE3, OMP and TuJ1)).

For immunofluorescence, the protocol was adapted as follows: Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:100; Jackson, 111515003) and Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated goat anti-mouse (1:100; Invitrogen) were used as secondary antibodies. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Invitrogen, D3571), and sections were subsequently mounted on slides with Dako mounting medium (S3023).

SARS-CoV S immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Immunohistochemical staining with mouse monoclonal anti-SARS spike glycoprotein antibodies (clone 3A2, ab272420, Abcam, 1:100) was performed using 1-μm-thick FFPE tissue sections. Slides were cooked in sodium citrate (pH 6.0; 95–100 °C) for 20 min, followed by enzymatic antigen retrieval with Triton X-100 and hydrogen peroxide for 15 min. Slides were blocked with 10% normal goat serum. Primary antibody (1:100, diluted in ProTaqs Antibody Diluent for IHC (Quartett) with 10% normal goat serum) was applied, and samples were incubated overnight. Then, secondary antibody (Biotin-SP-AffiniPure Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L), Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), diluted 1:100 in ProTaqs Antibody Diluent for IHC, was applied, and samples were incubated for 2 h. Next, Streptavidin-HRP Reagent (RE7104, Leica Biosystems) and DAB substrate–chromogen (Agilent) were applied according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Slides were rinsed, counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated and mounted.

Staining signals were compared to those of non-COVID-19 control samples with respect to the staining intensity and staining pattern as specified in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Fig. 5a–d; SARS-CoV S, Supplementary Table 2).

Image acquisition and processing

For fluorescence microscopy, an Olympus BX63 (DP80 camera) automated fluorescence microscope was used, if not specified otherwise, for confocal images. For confocal microscopy, fluorescence signals were collected with an Olympus FluoView FV1000 confocal microscope using a ×60 oil-immersion objective. For post‐acquisition image processing, the image analysis software Fiji was used48. For data handling of whole-slide images, an OME-TIFF workflow was used49.

Electron microscopy

Autopsy tissues were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.05 M sodium cacodylate, dehydrated using a graded acetone series and then infiltrated and embedded in Renlam resin. Block-contrasting with uranyl acetate and phosphotungstic acid was performed at the dehydration step with 70% acetone. 500-nm semithin sections were cut using an ultramicrotome (Ultracut E, Reichert-Jung) and a Histo Jumbo diamond knife (Diatome), transferred onto glass slides, stretched at 120 °C on a hot plate and stained with toluidine blue at 80 °C. 70-nm ultrathin sections were cut using the same ultramicrotome and an Ultra 35° diamond knife (Diatome), stretched with xylene vapor, collected onto pioloform-coated slot grids and then stained with lead citrate. Standard transmission EM was performed using a Zeiss 906 microscope in conjunction with a 2k CCD camera (TRS). Large-scale digitization was performed using a Zeiss Gemini 300 field-emission scanning electron microscope in conjunction with a STEM detector via Atlas 5 software at a pixel size of 4–6 nm. Regions of interest from the large-scale datasets were saved by annotation (‘mapped’) and then recorded at very high resolution using a pixel size of 0.5–1 nm.

Alternatively, ultrastructural analysis was performed from FFPE tissues. For virus detection, we took 3-mm punch biopsy cylinders from paraffin-embedded tissue. The respective regions were selected on the basis of the SARS-CoV ISH or immunohistochemistry signal. After deparaffinization in xylene, samples were rehydrated and postfixed in 1% formaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.05 M HEPES buffer (pH 7.2) for a minimum of 2–4 h at room temperature. Postfixation, block contrasting (tannic acid, uranyl acetate) and embedding in epon resin were performed according to a standard protocol50. Ultrathin sections were analyzed using a transmission electron microscope operated at 120 kV (Tecnai Spirit, Thermo Fisher), and images were recorded using a CCD camera (MegaviewIII, EMSIS).

Cytokine array

To analyze cytokine levels in CSF samples from deceased individuals with COVID-19 and controls (each n = 4), a human cytokine array (Bio-techne) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions27. We analyzed all CSF samples from individuals with COVID-19 accessible at the time of analysis. This assay enables the semiquantitative measurement of 36 cytokines and related proteins (CCL1, CCL2, MIP-1α, CCL5, CD40L, C5/C5a, CXCL1, CXCL10, CXCL11, CXCL12, G-CSF, GM-CSF, ICAM‑1, IFN-γ, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1ra, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12 p70, IL-13, IL‑16, IL-17A, IL-17E, IL-18, IL-21, IL-27, IL-32a, MIF, serpin E1, TNF-α, TREM-1). Twelve of these 36 cytokines were above the detection limit in our samples. Using the software Kodak D1 3.6 (Eastman Kodak), a semiquantitative analysis was performed by determining the background-corrected sum intensity for each region of interest on the membrane. Separate membranes were normalized to each other using the results for the positive controls. We could not perform a statistical test owing to the limited access to sufficient CSF samples. Data represent single data points and the mean, range and 25th and 75th percentiles.

In situ hybridization

For detection of mRNA, the RNAScope 2.5 HD Reagent Kit-BROWN (ACD Europe SRL) was used. Briefly, paraffin sections were freshly cut, dried for 1 h at 60 °C and dewaxed before mild unmasking with _target Retrieval buffer and protease. Pretreated sections were hybridized with specific probes to Ppib as a positive control and irrelevant probe to dapβ as a negative control (both ACD Europe SRL). Virus-specific probe V-ncoV2019-S (ACD Europe SRL) was used for samples from individuals with COVID-19 and was accompanied by an additional slide with FFPE lung tissue from an individual with COVID-19 (P15) as a further positive control. After hybridization signal amplification, binding of probes was visualized with DAB. Nuclei were stained with hematoxylin, and sections were coverslipped with Ecomount.

Images were acquired using an AxioImager Z1 microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging).

Statistics and reproducibility

All statistical analyses were performed and all graphs were created in GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software). No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample sizes; sample sizes in the current study are similar to those in previous COVID-19 autopsy reports by others4,32,38. We included all individuals with COVID-19 and material that were available as specified in the description of study design. The RT–qPCR analysis was replicated at least once for each positive sample. We did not exclude any data points from the performed analyses. To compute correlation between disease duration and viral load, Spearman nonparametric correlation was used. A two-tailed P value was calculated. Values were considered to be significant at P < 0.05. Statistical details for each analysis (for example, n, P and r values) are mentioned in each figure legend or in the respective part of the text. Owing to the nature of the investigation, data collection and analyses could not always be done in a blinded fashion. Histological staining, immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, ISH and EM results were analyzed independently by various neuropathologists in two distinct neuropathological institutions (Berlin and Göttingen) for each individual, region and specific staining/method. Histological staining, immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence and ISH analyses were replicated at least once. EM was performed in one individual. The representative micrographs shown were adjusted in brightness and contrast to different degrees (depending on the need resulting from the range of brightness and contrast of the raw images), rotated and cropped in Adobe Photoshop.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The three electron microscopy datasets in Supplementary Fig. 2 are available for open access pan-and-zoom analysis at http://www.nanotomy.org/.

References

Huang, C. et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395, 497–506 (2020).

Conde Cardona, G., Quintana Pájaro, L. D., Quintero Marzola, I. D., Ramos Villegas, Y. & Moscote Salazar, L. R. Neurotropism of SARS-CoV 2: mechanisms and manifestations. J. Neurol. Sci. 412, 116824 (2020).

Mao, L. et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients With coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127 (2020).

Puelles, V. G. et al. Multiorgan and renal tropism of SARS-CoV-2. N. Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2011400 (2020).

Moriguchi, T. et al. A first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-coronavirus-2. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 94, 55–58 (2020).

Otero, J. J. Neuropathologists play a key role in establishing the extent of COVID-19 in human patients. Free Neuropathology https://doi.org/10.17879/FREENEUROPATHOLOGY-2020-2736 (2020).

Zubair, A. S. et al. Neuropathogenesis and neurologic manifestations of the coronaviruses in the age of coronavirus disease 2019: a review. JAMA Neurol. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2065 (2020).

Cyranoski, D. Profile of a killer: the complex biology powering the coronavirus pandemic. Nature 581, 22–26 (2020).

Arbour, N., Day, R., Newcombe, J. & Talbot, P. J. Neuroinvasion by human respiratory coronaviruses. J. Virol. 74, 8913–8921 (2000).

Glass, W. G., Subbarao, K., Murphy, B. & Murphy, P. M. Mechanisms of host defense following severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus (SARS-CoV) pulmonary infection of mice. J. Immunol. 173, 4030–4039 (2004).

Li, K. et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus causes multiple organ damage and lethal disease in mice transgenic for human dipeptidyl peptidase 4. J. Infect. Dis. 213, 712–722 (2016).

Netland, J., Meyerholz, D. K., Moore, S., Cassell, M. & Perlman, S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection causes neuronal death in the absence of encephalitis in mice transgenic for human ACE2. J. Virol. 82, 7264–7275 (2008).

Hoffmann, M. et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 181, 271–280 (2020).

Doobay, M. F. et al. Differential expression of neuronal ACE2 in transgenic mice with overexpression of the brain renin–angiotensin system. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 292, R373–R381 (2007).

Lukassen, S. et al. SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are primarily expressed in bronchial transient secretory cells. EMBO J. 39, e105114 (2020).

Khan, S. & Gomes, J. Neuropathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. eLife 9, e59136 (2020).

Brann, D. H. et al. Non-neuronal expression of SARS-CoV-2 entry genes in the olfactory system suggests mechanisms underlying COVID-19-associated anosmia. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc5801 (2020).

Butowt, R. & Bilinska, K. SARS-CoV-2: olfaction, brain infection, and the urgent need for clinical samples allowing earlier virus detection. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 11, 1200–1203 (2020).

Schwob, J. E. Neural regeneration and the peripheral olfactory system. Anat. Rec. 269, 33–49 (2002).

Holbrook, E. H., Wu, E., Curry, W. T., Lin, D. T. & Schwob, J. E. Immunohistochemical characterization of human olfactory tissue: human olfactory tissue characterization. Laryngoscope 121, 1687–1701 (2011).

Carter, L. A., MacDonald, J. L. & Roskams, A. J. Olfactory horizontal basal cells demonstrate a conserved multipotent progenitor phenotype. J. Neurosci. 24, 5670–5683 (2004).

van Riel, D., Verdijk, R. & Kuiken, T. The olfactory nerve: a shortcut for influenza and other viral diseases into the central nervous system. J. Pathol. 235, 277–287 (2015).

Varga, Z. et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet 395, 1417–1418 (2020).

Goldsmith, C. S., Miller, S. E., Martines, R. B., Bullock, H. A. & Zaki, S. R. Electron microscopy of SARS-CoV-2: a challenging task. Lancet https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31188-0 (2020).

Goldsmith, C. S. & Miller, S. E. Modern uses of electron microscopy for detection of viruses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 22, 552–563 (2009).

Goldsmith, C. S. et al. Ultrastructural characterization of SARS coronavirus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10, 320–326 (2004).

Ksiazek, T. G. et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 1953–1966 (2003).

Blanchard, E. & Roingeard, P. Virus-induced double-membrane vesicles. Cell. Microbiol. 17, 45–50 (2015).

Tsai, S.-Y. et al. DAMP molecule S100A9 acts as a molecular pattern to enhance inflammation during influenza A virus infection: role of DDX21–TRIF–TLR4–MyD88 pathway. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1003848 (2014).

Körtvelyessy, P. et al. Serum and CSF cytokine levels mirror different neuroimmunological mechanisms in patients with LGI1 and Caspr2 encephalitis. Cytokine 135, 155226 (2020).

Oxley, T. J. et al. Large-vessel stroke as a presenting feature of Covid-19 in the young. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, e60 (2020).

Deigendesch, N. et al. Correlates of critical illness-related encephalopathy predominate postmortem COVID-19 neuropathology. Acta Neuropathol. 140, 583–586 (2020).

Schurink, B. et al. Viral presence and immunopathology in patients with lethal COVID-19: a prospective autopsy cohort study. Lancet Microbe https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30144-0 (2020).

Jensen, M. P. et al. Neuropathological findings in two patients with fatal COVID‐19. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. https://doi.org/10.1111/nan.12662 (2020).

Reichard, R. R. et al. Neuropathology of COVID-19: a spectrum of vascular and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM)-like pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 140, 1–6 (2020).

Schaller, T. et al. Postmortem examination of patients with COVID-19. JAMA 323, 2518–2520 (2020).

von Weyhern, C. H., Kaufmann, I., Neff, F. & Kremer, M. Early evidence of pronounced brain involvement in fatal COVID-19 outcomes. Lancet 395, e109 (2020).

Solomon, I. H. et al. Neuropathological features of Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 989–992 (2020).

Matschke, J. et al. Neuropathology of patients with COVID-19 in Germany: a post-mortem case series. Lancet Neurol. 19, 919–929 (2020).

Dittmayer, C. et al. Why misinterpretation of electron micrographs in SARS-CoV-2-infected tissue goes viral. Lancet https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32079-1 (2020).

Paniz‐Mondolfi, A. et al. Central nervous system involvement by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2). J. Med. Virol. 92, 699–702 (2020).

Wiersinga, W. J., Rhodes, A., Cheng, A. C., Peacock, S. J. & Prescott, H. C. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA 324, 782–793 (2020).

Desforges, M., Le Coupanec, A., Brison, E., Meessen-Pinard, M. & Talbot, P. J. Neuroinvasive and neurotropic human respiratory coronaviruses: potential neurovirulent agents in humans. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 807, 75–96 (2014).

Baig, A. M., Khaleeq, A., Ali, U. & Syeda, H. Evidence of the COVID-19 virus _targeting the CNS: tissue distribution, host–virus interaction, and proposed neurotropic mechanisms. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 11, 995–998 (2020).

Wang, Y.-Z. et al. Olig2 regulates terminal differentiation and maturation of peripheral olfactory sensory neurons. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-019-03385-x (2019).

Corman, V. M. et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT–PCR. Euro. Surveill. 25, 2000045 (2020).

Wölfel, R. et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature 581, 465–469 (2020).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012).

Besson, S. et al. Bringing open data to whole slide imaging. Digit. Pathol. 2019, 3–10 (2019).

Laue, M. Electron microscopy of viruses. Methods Cell. Biol. 96, 1–20 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to F. Egelhofer, R. Koll, P. Matylewski, K. Permien, V. Wolf, S. Meier, R. Müller, U. Scheidt, K. Guttek, F. Paap, B. Maruschak and K. Schulz for excellent technical assistance and advice. We thank the Core Facility for Electron Microscopy of the Charité for support in acquisition of the data. We also thank H. Bohnenberger, S. Küffer and the Institute of Pathology of the University Medical Center, Göttingen, for their support. The authors are most grateful to the individuals with COVD-19 and their relatives for consenting to autopsy and subsequent research, which were facilitated by the Biobank of the Department of Neuropathology, Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin. Cartoon images were partially created with Biorender.com. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy EXC-2049-390688087, as well as SFB TRR 167 and HE 3130/6-1 to F.L.H., SFB 958/Z02 to J.S., SFB TRR 130 TP17 to H.R., EXC 2067/1-390729940, SFB TRR 274 and STA 1389/5-1 to C.S. and SFB TRR 241 to B.S. and A.A.K., by the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE) Berlin, by the European Union (PHAGO, 115976; Innovative Medicines Initiative-2; FP7-PEOPLE-2012-ITN: NeuroKine) and by the Ministry for Science and Education of Lower Saxony through the program ‘Niedersächsisches Vorab’ to J.F. Furthermore, we thank the Charité Foundation (Max Rubner Preis 2016) for financial support to C. Dittmayer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M., J.R., R.M., J.F., C.T., O.H., M.W., L.R., H.M., W.J.S.-S., C.S., S.H., M.S.W., B.T., F.S., P.K., M.L., A.A.K., T.A., S.G., E.S., D.R., A.N., B.S., R.L.C., C.C., R.E., S.E., D.H., L.O., M.T, B.I.-H., H.R. and F.L.H. performed clinical workup and section and/or histological analyses. C. Dittmayer, H.-H.G., H.R.G., M.L. and W.S. performed ultrastructural analyses. J.S., S.B., C. Drosten and V.M.C. carried out viral RT–qPCR analyses. All authors contributed to the experiments and analyzed data. H.R. and F.L.H. designed and supervised the study. J.M., J.R., H.R. and C. Dittmayer prepared the figures. All authors wrote, revised and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Neuroscience thanks Roxana Carare and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–6 and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Meinhardt, J., Radke, J., Dittmayer, C. et al. Olfactory transmucosal SARS-CoV-2 invasion as a port of central nervous system entry in individuals with COVID-19. Nat Neurosci 24, 168–175 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-020-00758-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-020-00758-5

This article is cited by

-

Mucosal immune response in biology, disease prevention and treatment

Signal Transduction and _targeted Therapy (2025)

-

Neurological, psychological, psychosocial complications of long-COVID and their management

Neurological Sciences (2025)

-

EEG signatures of cognitive decline after mild SARS-CoV-2 infection: an age-dependent study

BMC Medicine (2024)

-

Randomized controlled double-blind trial of methylprednisolone versus placebo in patients with post-COVID-19 syndrome and cognitive deficits: study protocol of the post-corona-virus immune treatment (PoCoVIT) trial

Neurological Research and Practice (2024)

-

Contribution of CNS and extra-CNS infections to neurodegeneration: a narrative review

Journal of Neuroinflammation (2024)