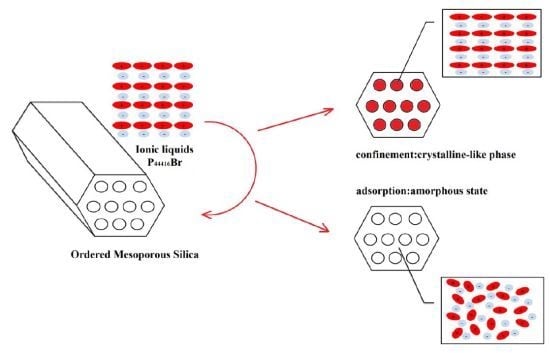

The Influence of Silica Nanoparticles on Ionic Liquid Behavior: A Clear Difference between Adsorption and Confinement

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Materials

3.2. Experimental Details

3.3. Characterizations

4. Conclusions

| P44416Br | P44416Br@SiO2 | P44416Br/SiO2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enthalpy of fusion/J·g−1 | 73.02 | 21.67 | 17.90 |

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Welton, T. Room-temperature ionic liquids. Solvents for synthesis and catalysis. Chem. Rev 1999, 99, 2071–2083. [Google Scholar]

- Hallett, J.P.; Welton, T. Room-Temperature Ionic Liquids: Solvents for Synthesis and Catalysis. 2. Chem. Rev 2011, 111, 3508–3576. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Deng, Y. Recent advances in ionic liquid catalysis. Green Chem 2011, 13, 2619–2637. [Google Scholar]

- Neouze, M.-A.; Le Bideau, J.; Gaveau, P.; Bellayer, S.; Vioux, A. Ionogels, new materials arising from the confinement of ionic liquids within silica-derived networks. Chem. Mater 2006, 18, 3931–3936. [Google Scholar]

- Neouze, M.A.; Le Bideau, J.; Leroux, F.; Vioux, A. A route to heat resistant solid membranes with performances of liquid electrolytes. Chem. Commun 2005, 1082–1084. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, F.; Zhang, Q.H.; Li, D.M.; Deng, Y.Q. Silica-gel-confined ionic liquids: A new attempt for the development of supported nanoliquid catalysis. Chem. Eur. J 2005, 11, 5279–5288. [Google Scholar]

- Goebel, R.; Friedrich, A.; Taubert, A. Tuning the phase behavior of ionic liquids in organically functionalized silica ionogels. Dalton Trans 2010, 39, 603–611. [Google Scholar]

- Kanakubo, M.; Hiejima, Y.; Minami, K.; Aizawa, T.; Nanjo, H. Melting point depression of ionic liquids confined in nanospaces. Chem. Commun 2006, 1828–1830. [Google Scholar]

- Im, J.; Cho, S.D.; Kim, M.H.; Jung, Y.M.; Kim, H.S.; Park, H.S. Anomalous thermal transition and crystallization of ionic liquids confined in graphene multilayers. Chem. Commun 2012, 48, 2015–2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, G.; Fu, H.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, S.; Sha, M. Immobilization and melting point depression of imidazolium ionic liquids on the surface of nano-SiOx particles. Dalton Trans 2010, 39, 3190–3194. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Liu, Y.; Fu, H.; He, Y.; Li, C.; Huang, W.; Jiang, Z.; Wu, G. Unravelling the role of the compressed gas on melting point of liquid confined in nanospace. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2012, 3, 1052–1055. [Google Scholar]

- Ariga, K.; Vinu, A.; Yamauchi, Y.; Ji, Q.; Hill, J.P. Nanoarchitectonics for mesoporous materials. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn 2012, 85, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.-R.; Sculley, J.; Zhou, H.-C. Metal-organic frameworks for separations. Chem. Rev 2012, 112, 869–932. [Google Scholar]

- Amouri, H.; Desmarets, C.; Moussa, J. Confined nanospaces in metallocages: Guest molecules, weakly encapsulated anions, and catalyst sequestration. Chem. Rev 2012, 112, 2015–2041. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.D.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, G.Z.; Hu, J. Coexistence of liquid and solid phases of Bmim-PF6 ionic liquid on mica surfaces at room temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 7456–7457. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Fu, H.; Li, C.; Ji, X.; Ge, X.; Zou, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Xu, H.; Wu, G. Property variation of ionic liquid Bmim AuCl4 immobilized on carboxylated polystyrene submicrospheres with a small surface area. Chin. Sci. Bull 2013, 58, 2950–2955. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Wu, G.; Sha, M.; Huang, S. Transition of ionic liquid bmim PF6 from liquid to high-melting-point crystal when confined in multiwalled carbon nanotubes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 2416–2417. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Guo, X.; He, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Fu, H.; Zou, Y.; Dai, S.; Wu, G.; et al. Compression of ionic liquid when confined in porous silica nanoparticles. RSC Adv 2013, 3, 9618–9621. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Ji, S.; Xiao, T.; Guo, C.; Wu, P.; Nie, P. Preparation and characterization of tungsten carbide confined in the channels of SBA-15 mesoporous silica. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 3599–3608. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.-S.; Fu, H.-Y.; Tang, Z.-F.; Huang, W.; Wu, G.-Z. Melting point and structure of ionic liquid EMIM PF6 on the surface of Nano-SiOx particles. Acta Phys. Chim. Sin 2011, 27, 1725–1729. [Google Scholar]

- Trofymluk, O.; Levchenko, A.A.; Navrotsky, A. Interfacial effects on vitrification of confined glass-forming liquids. J. Chem. Phys 123, 09.

- Huck, W.T.S. Effects of nanoconfinement on the morphology and reactivity of organic materials. Chem. Commun 2005, 4143–4148. [Google Scholar]

- Golovanov, D.G.; Lyssenko, K.A.; Antipin, M.Y.; Vygodskii, Y.S.; Lozinskaya, E.I.; Shaplov, A.S. Extremely short C–H center dot center dot center dot F contacts in the 1-methyl-3-propylimidazolium SiF6-the reason for ionic “liquid” unexpected high melting point. Crystengcomm 2005, 7, 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Sha, M.; Wu, G.; Liu, Y.; Tang, Z.; Fang, H. Drastic phase transition in ionic liquid dmim CI confined between graphite walls: New phase formation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 4618–4622. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, K.; Zhou, G.; Liu, X.; Yao, X.; Zhang, S.; Lyubartsev, A. Structural evidence for the ordered crystallites of ionic liquid in confined carbon nanotubes. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 10013–10020. [Google Scholar]

- Sha, M.; Wu, G.; Fang, H.; Zhu, G.; Liu, Y. Liquid-to-solid phase transition of a 1,3-dimethylimidazolium chloride ionic liquid monolayer confined between graphite walls. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 18584–18587. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, Q.; Sha, M.; Fu, H.; Wu, G. Melting transition of ionic liquid bmim PF6 crystal confined in nanopores: A molecular dynamics simulation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 18946–18951. [Google Scholar]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Guo, X.; Wu, G. The Influence of Silica Nanoparticles on Ionic Liquid Behavior: A Clear Difference between Adsorption and Confinement. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 21045-21052. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms141021045

Wang Y, Li C, Guo X, Wu G. The Influence of Silica Nanoparticles on Ionic Liquid Behavior: A Clear Difference between Adsorption and Confinement. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013; 14(10):21045-21052. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms141021045

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yaxing, Cheng Li, Xiaojing Guo, and Guozhong Wu. 2013. "The Influence of Silica Nanoparticles on Ionic Liquid Behavior: A Clear Difference between Adsorption and Confinement" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 14, no. 10: 21045-21052. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms141021045

APA StyleWang, Y., Li, C., Guo, X., & Wu, G. (2013). The Influence of Silica Nanoparticles on Ionic Liquid Behavior: A Clear Difference between Adsorption and Confinement. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 14(10), 21045-21052. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms141021045