The prevalence of obesity and associated chronic diseases, i.e. cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, is rapidly increasing in all parts of the world(Reference Kopelman1). The current number of diabetes patients is 143 million worldwide, and 200 million people are estimated to have type 2 diabetes by 2030(Reference Wild, Roglic, Green, Sicree and King2). Obesity, characterized by excessive accumulation of adipose tissue especially around the waist, increases the risk to various metabolic disorders including dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction and hypertension. Metabolic syndrome, which can be considered as a prediabetic state, is diagnosed by increased central obesity, elevated serum triglycerides, reduced HDL cholesterol, raised blood pressure or raised fasting plasma glucose (IDF, 2006 – IDF Consensus Worldwide Definition of the Metabolic Syndrome, http://www.idf.org). Thus diabetes is associated with defects in the glucose and insulin metabolism in muscle, adipose tissue and liver which are manifested by reduced insulin sensitivity and secretion and higher resistance to insulin action. Oxidative stress and sub-clinical grade inflammation can play a significant role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. Therefore several antioxidant sources in foods have potential benefits in the amelioration of obesity related diseases.

Diet plays an important role in the aetiology and prevention of several obesity-associated chronic diseases, most notably of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. Dietary pattern characterized by higher consumption of vegetables, fruits and whole grains is associated with reduced risk of type 2 diabetes(Reference van Dam, Willett, Rimm, Stampfer and Hu3). The evidence for individual dietary components is limited, but phytochemicals, a large group of non-nutrient secondary metabolites in plants which provide much of the colour and taste in fresh or processed fruits and vegetables, are thought to play a significant role in the health effects of plant-based diets. Especially the antioxidant effects of phytochemicals such as polyphenols or carotenoids have been studied extensively, but less is known of the other possible biological mechanisms linking phytochemicals to the prevention of type 2 diabetes.

Multiple _targeted effects of phytochemicals in type 2 diabetes

Amelioration of the oxidative stress

Diabetes is associated with oxidative stress due to hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia(Reference Baynes and Thorpe4). Hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia (increased level of fatty acids and TAG-rich and modified lipoproteins) induce inflammatory-immune responses and oxidative stress reactions, and generation of free radicals accounts for the cardiovascular complications and mortality of obesity and type 2 diabetes(Reference Baynes and Thorpe4, Reference Pickup5).

The depletion of antioxidants and its contribution to cardiovascular complications in diabetes is well documented(Reference Baynes and Thorpe4–Reference Chertow6). Several studies have demonstrated significant decrease of plasma antioxidants such as of α- and γ-tocopherol, β- and α-carotene, lycopene, β-cryptoxanthin, lutein, zeaxanthin, retinol, as well as ascorbic acid in the course of diabetes and its associated complications such as endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis(Reference Polidori, Mecocci and Stahl7–Reference Valabhji, McColi and Richmond10). Low levels of plasma antioxidants are even more pronounced in elderly diabetic subjects(Reference Polidori, Stahl and Eichler8). Thus the rationale for the therapeutic use of antioxidants in the treatment and prevention of diabetic complications is strong.

Flavonoids, carotenoids, ascorbic acid and tocopherols are the main antioxidants recommended based on the results from experimental models(Reference Pietta11, Reference Middleton, Kandaswami and Theoharides12). They have been shown to inhibit ROS production by inhibiting several ROS producing enzymes (i.e. xanthine oxidase, cyclooxygenase, lipoxygenase, microsomal monooxygenase, glutathione-S-transferase, mitochondrial succinoxidase, NADH oxidase), and by chelating trace metals and inhibiting phospholipases A2 and C(Reference Manach, Mazur and Scalbert17). They act by donating a hydrogen atom/electron to the superoxide anion and also to hydroxyl, alkoxyl and peroxyl radicals thereby protecting lipoproteins, proteins as well as DNA molecules against oxidative damage(Reference Pietta11, Reference Noguchi and Nikki13). However, free radicals as well as some antioxidative vitamin derivatives (i.e. retinoic acid) are also important regulators of cellular functions including gene expression, differentiation, preconditioning (mitochondrial function) and apoptosis etc(Reference Chertow6).

Although many earlier epidemiological studies have reported lower risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in populations with higher intakes and higher blood levels of antioxidants, the large scale trials with antioxidant supplementation have failed to confirm any protective effect by antioxidants on cardiovascular mortality in spite improving the biochemical parameters of lipoprotein oxidation (reviewed by Clarke & Armitage(Reference Clarke and Armitage14)). Nevertheless, the available evidence does not contradict the advice to increase consumption of fruit and vegetables to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease especially in patients with diabetes(Reference Chertow6).

Anti-inflammatory and antiatherogenic effects

Low-grade inflammation (also called a sub-clinical inflammatory condition) and the activation of the innate immune system are closely involved in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes and associated complications such as dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis(Reference Pickup15). Especially the development of obesity related insulin resistance have been linked to cytokines tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin 6 (IL-6) produced by the adipose tissue. Major tissue specific pathways involved in the inflammatory process have been suggested to depend on nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and c-jun terminal NH2-kinase (JNK) signalling pathways(Reference Bastard, Maachi, Lagathu, Kim, Caron, Vidal, Capeau and Feve16). A strong negative correlation between polyphenols consumption and CAD and stroke has been documented(Reference Manach, Mazur and Scalbert17). However, a major difficulty with these correlative studies is the extreme complexity of the polyphenols in food and beverages. Several hundreds of phenolic compounds have been described in foods including flavonoids and non-flavonoids (phenolic acids, stilbenes and lignans).

There is increasing evidence of potential benefits of polyphenols in the regulation of cellular processes such as redox control and inflammatory responses as established in animal models or cultured cells. In the apoE KO mice model, polyphenols from red wine and green tea were shown to prevent the formation of atherosclerotic plaques(Reference Norata, Marchesi and Passamonti18). This antiatherosclerotic effect may be associated both with modification of oxidative stress and/or with lipid-lowering effect of the polyphenols(Reference Hayek, Fuhrman and Vaya19, Reference Waddington, Puddey and Croft20). The anti-inflammatory effect is due to decreased recruitment of monocyte-macrophages and T-lymphocytes and decreased chemokines and cytokines or its receptors. Resveratrol, catechin and quercetin interact with the NF-κB signalling pathway by inhibiting the expression of the adhesion molecules, ICAM-1 and VCAM, in endothelial cells as well as expression of MCP-1, MIP-1α and MIP-1β and the chemokine receptors CCR1 and CCR2(Reference Norata, Marchesi and Passamonti18, Reference Pellegatta, Bertelli and Staels21). The latter inhibit the chemotaxis and leukocyte recruitment resulting in decrease of IL-6, VEGF, TGFβ, but also IL-10 indicating decreased Th1 and Th2 recruitment.

Metabolites of blueberry polyphenols produced by gut flora have been shown to decrease the inflammation in vitro as measured by prostanoid production(Reference Russell22, Reference Youdim, McDonald, Kalt and Joseph23). Beneficial immune responses have been shown in human endothelial cells upon exposure to these anthocyanin metabolites at doses comparable to those found in plasma after blueberry and cranberry administration(Reference Youdim, McDonald, Kalt and Joseph23). Anthocyanin metabolites reduced TNF-alpha induced expression of IL-8, MCP-1 and ICAM-1 while reducing the oxidative damage. Inhibition of COX-2 by anthocyanidins was mediated with MAPK-pathway in LPS-evoked macrophages in vitro (Reference Hou, Yanagita, Uto, Masuzaki and Fujii24, Reference Pergola, Rossi, Dugo, Cuzzocrea and Sautebin25). The main anthocyanin in the blackberry extract, cyanidine-3-O-glucoside, was shown to inhibit the iNOS biosynthesis(Reference Pergola, Rossi, Dugo, Cuzzocrea and Sautebin25). Asthma related inflammation can also be reduced by anthocyanins via COX-2 inhibition as shown in a murine model (in vivo). In this asthma model anthocyanins were also found to reduce Th2 regulated cytokine expressions (mRNA of TNF-alpha, IL-6, IL-13, IL-13 R2alpha). One key transcription factor in obesity related inflammation is NF-κB. The effects of anthocyanins in inhibition of NF-κB has been studied in a human intervention study using a blackcurrant and bilberry supplementation product “Medox” with 300 mg/d(Reference Karlsen, Retterstøl, Laake, Paur, Kjølsrud-Bøhn, Sandvik and Blomhoff26). In addition to inhibition of NF-κB in a cell culture model, NF-κB mediated cytokines IL-8 and INF alpha was significantly reduced.

Glucose and lipid metabolism

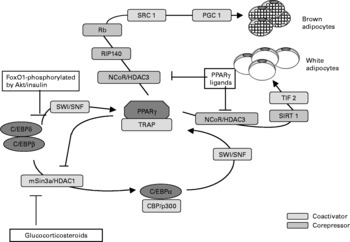

A number of regulatory mechanisms help the body to maintain glucose and lipid homeostasis and stable levels of energy stores. Such mechanisms involve control of metabolic fluxes among various organs and energy metabolism within individual tissues and cells(Reference Chertow6). Many types of mammalian cells can directly sense changes in the levels of variety of macronutrients (glucose, fatty acids and amino acids) or the related enzymes etc of their catabolism, such as AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK, the metabolic stress sensor); mammalian _target of rapamycin (mTOR), protein kinase (MAPK, the amino-acid and metabolic state sensor), Per-Arnt-Sin (PAS) kinase (sensor of oxygen/redox status), hexosamine synthetic pathway flux (HBP) (insulin sensing), or NAD+-dependent protein deacetylase SIRT2 (sensor of the long-term energy restriction) involved in longevity(Reference McCue, Kwon and Shetty28) (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1 Some of common mechanisms regulating the cellular response to “nutrient-energy sensing” pathway including AMP-regulating kinase and mammalian _target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways.

Fig. 2 The main transcriptor factors induced by insulin, glucocorticosteroids, cAMP and mitogens during adipogenesis.

Regulation of the postprandial glucose by inhibiting starch digestion, delaying the gastric emptying rate and reducing active transport of glucose across intestinal brush border membrane is one of the mechanisms by which diet can reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes. Thus inhibition of intestine sodium–glucose cotransporter-1 (Na-Glut-1) along with inhibition of α-amylase and α-glucosidase activity by plant phenols make them a potential candidate in the management of hyperglycemia(Reference Heilbronn, Smith and Ravussin29, Reference Kobayashi, Saito, Nakazawa and Yoshizaki30).

Tea and several plant polyphenols were reported to inhibit α-amylase and sucrase activity, decreasing postprandial glycemia(Reference Kobayashi, Saito, Nakazawa and Yoshizaki30). Individual polyphenols, such as (+)catechin, ( − )epicatechin, ( − )epigallocatechin, epicatechin gallate, isoflavones from soyabeans, tannic acid, glycyrrhizin from licorice root, chlorogenic acid and saponins also decrease S-Glut-1 mediated intestinal transport of glucose (reviewed by Tiwari(Reference Tiwari and Rao31)). Saponins additionally delay the transfer of glucose from stomach to the small intestine(Reference Francis, Kerem, Makkar and Becker32). The water-soluble dietary fibres, guar gum, pectins and polysaccharides contained in plants are known to slow the rate of gastric emptying and thus absorption of glucose. The α-glucosidase inhibitors (acarbose and the others) are presently recommended for the treatment of obesity and diabetes. Phytochemicals have been shown to demonstrate such as activity(Reference Watanabe, Kawabata, Kurihara and Niki33).

Anthocyanins, a significant group of polyphenols in bilberries and other berries, may also prevent type 2 diabetes and obesity. Anthocyanins from different sources have been shown to affect glucose absorption and insulin level/secretion/action and lipid metabolism in vitro and in vivo (Reference Tsuda, Ueno, Kojo, Yoshikawa and Osawa35–Reference Martineau, Couture, Spoor, Benhaddou-Andaloussi, Harris, Meddah, Leduc, Burt, Vuong, Mai Le, Prentki, Bennett, Arnason and Haddad37). Blueberry extracts were found to be potent inhibitors of starch digestion, and more effective inhibitors of the α-glucosidase/maltase activity than extracts from strawberry and raspberry. Martineau and his group (2006) reported that extracts from the high bush blueberry (V. angustifolium) also increase glucose uptake by the muscle cells in the presence of insulin and protect the neural cells from the toxic effects of high glucose levels in vitro (Reference Martineau, Couture, Spoor, Benhaddou-Andaloussi, Harris, Meddah, Leduc, Burt, Vuong, Mai Le, Prentki, Bennett, Arnason and Haddad37). Other in vitro studies with pancreatic cells have shown that pure anthocyanins (glucose conjugates) such as delfinidin glucosides, cyanidin glycosides and cyanidin galactosides can increase the excretion of insulin in primary cell cultures(Reference Martineau, Couture, Spoor, Benhaddou-Andaloussi, Harris, Meddah, Leduc, Burt, Vuong, Mai Le, Prentki, Bennett, Arnason and Haddad37). Anthocyanins also influence the expression of genes involved in cell cycle, signal transduction, lipid and carbohydrate metabolism in adipocytes isolated from rats(Reference Jayaprakasam, Vareed, Olson and Nair36) and human tissues(Reference Xia, Ling, Ma, Xia, Hou, Wang, Zhu and Tang39). These in vitro studies suggest that the anthocyanins may decrease the intestinal absorption of glucose by retarding the release of glucose during digestion.

Tsuda and his co-workers have also studied the colourful extract of purple corn (PCC) containing anthocyanins with respect of its possible effects in obesity and diabetes(Reference Tsuda, Horio, Uchida, Aoki and Osawa34). Purple corn colour contains high amounts of cyanidin glucoside (70 g/kg) and it is used as a food colouring agent in beverages. They fed mice for 12 weeks with a high fat diet (HFD) or a normal diet with or without 2 g/kg cyanidin glucosides. The animals fed with HFD had higher body weight and weights of brown and white adipose tissues (hypertrophy) and increased triglycerides and total fat content in liver, but not in serum. Serum insulin, leptin and TNF-α (mRNA) were also increased after feeding with this diet. All of these effects of HFD feeding were decreased in mice fed a diet with PCC. Similar effects have been observed with high fat diets rich in anthocyanins from Cornelian cherries and black rice(Reference Martineau, Couture, Spoor, Benhaddou-Andaloussi, Harris, Meddah, Leduc, Burt, Vuong, Mai Le, Prentki, Bennett, Arnason and Haddad37, Reference Johnston, Clifford and Morgan40). In many of the studies utilizing the HFD model the sources of anthocyanins are not fully described. Therefore, a detailed analysis of the contents of extracts as well as the contents of diets could provide valuable information to further evaluate the effective components in these diets. Thus far only one other human study on anthocyanins has been reported and it showed that consumption of chokeberry, a berry that contains as much antocyanins as bilberries, decreases fasting glucose and serum cholesterol and decreases HbA1C in type 2 diabetic patients(Reference Jahromi and Ray42).

In addition to anthocyanins, chlorogenic acid also present in wild berries may also explain some of their potential health effects in obesity related diseases. Indeed, several studies on coffee rich in chlorogenic acid suggested some beneficial effects of this compound. Johnston and his co-workers studied the effect of coffee on the absorption of glucose from a single dose (25 g, 2·5 mmol/l chlorogenic acid) in humans(Reference Johnston, Clifford and Morgan40). They suggested that chlorogenic acid could disrupt the Na-gradient that is needed in the transport of glucose from the proximal duodenum.

Cytoprotection of pancreatic β-cells (maintaining of insulin secretion)

Cytoprotection of pancreatic β-cells was demonstrated for the extracts containing phytochemicals (liquiritigenin, pterosupin) from several medicinal plants: Pterocarpus marsupium, Gymnemaq sylvestre (Reference Chakravarthy, Gupta and Gode43, Reference Ignacimuthy and Amalraj44), as well as Zizyphus jujuba or Trigonella foenum-graceum L. fenugreek seeds(Reference Ravicumar and Anuradha45, Reference Young, Dragstedt, Haraldsdottir, Daneshvar, Kal, Loft, Nilsson, Nielsen, Mayer, Skibsted, Huynh-Ba, Hermetter and Sandstrom46) in streptozotocin or alloxan-induced model of diabetic rats. The antioxidant effects of the above flavonoids were demonstrated by the decrease of lipid peroxidation, as well as by increased plasma levels of glutathione and beta-carotene(Reference Young, Dragstedt, Haraldsdottir, Daneshvar, Kal, Loft, Nilsson, Nielsen, Mayer, Skibsted, Huynh-Ba, Hermetter and Sandstrom46). Water-soluble extracts of the Gymnema sylvestre leaves given for 10–12 months to control glycemia and lipidemia enhanced endogenous insulin secretion in 27 IDDM patients(Reference Shanmugasundaram, Rajeswari and Baskaran47). Also the fenugreed seeds have been reported to exert hypoglycemic and lipid normalizing effects(Reference Sharma and Raghuram48, Reference Sharma, Raghuram and Dayasagar Rao49).

Inhibition of aldose reductase (the polyol pathway)

Accumulation of sorbitol, the metabolite of polyol reductase pathway, plays an important role in diabetic complications such as retinopathy, cataract, neuropathy and nephropathy. Apart from their common antioxidant activity, several plant-derived flavonoids can increase aldose reductase activity, ameliorating the complications of diabetes in experimental models(Reference Iwata, Nagat and Omae50, Reference Yoshikawa, Morikawa and Murakami51). Recently butein (tetrahydrochalcone) was reported to be a potent antioxidant and a compound that inhibits aldose reductase in the treatment of the side effects observed in rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes(Reference Lim, Jung, Shin and Keum52).

Improvement of endothelial dysfunction

Plant polyphenols exert also vasorelaxant, anti-angiogenic and anti-proliferative effects on cells of the vascular wall such as endothelium or vascular smooth muscle(Reference Stoclet, Chataigneau and Ndiaye53). Epigallocatechin gallate decreases vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and thereby reduces the capillary thickness and inhibits vessel remodeling(Reference Flesch, Schwarz and Bohm55). Plant phenols induce vasorelaxation by the induction of endothelial nitric oxide synthesis or increased bioavailability and the NO-cGMP pathway(Reference Chyu, Babbidge and Zhayo54, Reference Liu, Chen and Chan56). The inhibition of vasoconstrictory endothelin-1 by polyphenols in human and bovine endothelium has been also reported(Reference Rupnick, Panigrahy and Zhang57). Thus the beneficial effects of phytochemicals on endothelial function are well documented.

Inhibition of angiogenesis

Without the appropriate blood supply by blood and lymph capillary network, tissues cannot survive because the circulatory system is essential for the oxygen and nutrient distribution between tissues and for the removal of by-products of metabolism. Vasculogenesis and angiogenesis play an essential role in a number of physiologic and pathologic events such as fetal development, vascular and tissue remodeling in ischemia, inflammation and proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Vascularity is critical also for the function of adipose tissue as a metabolic and an endocrine organ. It has been shown recently that treatment of animals with antiangiogenic factors, (such as anti VEGF or its receptor antibody) dose-dependently and reversibly decreases the adipose tissue depot and body weight(Reference Higami, Barger and Page58). Angiogenesis may play an important role in the diabetic microangiopathy and inflammation (macrophage infiltration) of the adipose tissue and also in the control of adipose tissue mass(Reference Fain, Madan and Hiler59, Reference Losso60) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Some of corregulators involved in adipogenesis and the possible regulation by PPARγ ligands, glucocorticoides, insulin/Akt and histone deacetylases including sirtuin-1. TRAP – thyroid-hormone receptor-associated protein, FoxO1 – forkhead transcription factor.

The possibility of the control of pathological angiogenesis (including age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and diabetes) by nutraceuticals has been reviewed by Losso(Reference Losso60). Several classes of compounds including catechins, curcumin, isoflavones, polymeric proanthocyanidins and flavonoids, saponins and terpenes, vitamins, and their possible mechanisms of function have been discussed in this review. Anti-angiogenic effect of polyphenols depends mainly on the inhibition of the p38 MAPK-mediated expression of the VEGF gene(Reference Dembinska-Kiec, Polus and Kiec-Wilk62). On the other hand, our experimental results indicate that carotenoids such as β-carotene may promote angiogenesis by activating chemotaxis of endothelial cells and its progenitors(Reference Brakenhielm, Cao and Cao63). Thus in diabetes which displays both excessive and insufficient angiogenesis, compounds that may inhibit excessive angiogenesis and exacerbate insufficient angiogenesis need to be identified. Brakenhielm et al. (Reference Brakenhielm, Cao and Cao63) demonstrated that the resveratrol, a red wine compound with beneficial antioxidative effects and stimulator of the sirtuin (“the longevity gene”), caused wound enlargement in the diabetic rat model. Delayed wound healing is a known complication of diabetes caused by microangiopathy and endothelial dysfunction. Retinoids prevent angiogenesis and with green tea catechins inhibit angiogenesis. Compounds exerting the thermogenic, as well as anti-angiogenic activity also demonstrate the antiobesity effects(Reference Cao65).

Phytochemicals and gene expression

The effects of phytochemicals on gene expression in different tissues and cells have been of intensive research still ongoing to specify the mechanisms and novel _targets of therapeutic nutrients. Polyphenolic phytochemicals may also influence expression of genes relevant for the development of type 2 diabetes, i.e. genes regulating glucose transport, insulin secretion or action, antioxidant effect, inflammation, vascular functions, lipid metabolism, thermogenic or other possible mechanisms. These effects have been studied using in vitro, animal and human ex vivo models from muscle and adipose tissues as well as mRNA analysis of human PBMC(Reference Thirunavukkarasu, Penumathsa, Koneru, Juhasz, Zhan, Otani, Bagchi, Das and Maulik66–Reference Moskaug, Carlsen, Myhrstad and Blomhoff68).

Several rodent models of diabetes have provided gene expression data of different _target tissues. The effects of polyphenolic compounds have been investigated in several models of obesity. Resveratrol has been found to induce p-AKT, p-eNOS, Trx-1, HO-1, and VEGF in addition to increased activation of MnSOD activity in STZ-induced diabetic rat myocardium compared to non-diabetic animals through NOS(Reference Thirunavukkarasu, Penumathsa, Koneru, Juhasz, Zhan, Otani, Bagchi, Das and Maulik66). Resveratrol has been found to increase the expression of GLUT-4 in muscle of STZ-induced diabetic rats via PI3K-Akt pathways. Decreased expression of GLUT-4, the major glucose transporter in muscle has been observed in diabetes(Reference Das67). Also a high fat diet (HFD) mouse model has proven to be useful in measuring diet induced obesity related diseases. The most used mouse strain in HFD feeding model is C57BL/6J that has been widely applied with varying source and amount of dietary fat. In mice fed anthocyanin rich purple corn colour (PCC) to ameliorate weight gain, gene expression of enzymes involved in the fatty acid and triacylglycerol synthesis and the sterol regulatory element binding protein-1 (SREBP-1) levels in white adipose tissue were reduced(Reference Tsuda, Horio, Uchida, Aoki and Osawa34). In a cell culture model of rat adipocytes the treatment of anthocyanins PPAR gamma and _target adipocyte specific genes (LPL, aP2, and UCP2) were significantly up-regulated. Leptin and adiponectin as well as their mRNA levels were also increased by anthocyanins resulting from the increased phosphorylated MAPK. The mechanisms of action of anthocyanins in the amelioration of obesity can be mediated by upregulation of the thermogenic mithocondrial uncoupling protein 2 (UCP-2) and the lipolytic enzyme hormone sensitive lipase (HSL) as well as by down-regulation of the nuclear factor plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1)(Reference Jayaprakasam, Vareed, Olson and Nair36). Some of the previous findings have been also discovered in human adipocytes treated with anthocyanins(Reference Tsuda, Ueno, Yoshikawa, Kojo and Osawa38). Further studies using a diabetic mouse model KK-Ay-mice have shown similar differences after anthocyanin and cyanidin-3-glucoside administration. Gene expression of TNF-α and MCP-1 in mesenteric WAT was decreased and GLUT-4 increased, while a novel potential _target gene retinol binding protein-4 was significantly decreased by 2 g/kg anthocyanin in diet. The anthocyanin treatment enhanced the energy expenditure related genes UCP-2 and adiponectin and downregulation of PAI-1 that is induced by IL-6 in obese subjects, which suggests that also anti-inflammatory mechanisms of anthocyanins are involved(Reference Moskaug, Carlsen, Myhrstad and Blomhoff68, Reference Abahusian, Wright, Dickerson and Vol69) (Figs. 4 and 5).

Fig. 4 Adipogenesis is associated with angiogenesis. The proangiogenic factors including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), nitric oxide (NO) metalloproteinases, chemotactive factors, tissue activator and inhibitor ofplasmin (tPA/PAI) and others are released from vascular stromal cells (SVF) as well as by adipocytes and infiltrating adipose tissue macrophages.

Fig. 5 The possible mechanisms of the phytochemical activity in the amelioration of symptomes of diabetes type 2 (modified after Tiwari & Rao(Reference Tiwari and Rao31)).

Quercetin has been found to regulate gene expression mainly via NF-κB, xenobiotic responsive elements and antioxidant responsive elements (ARE) (reviewed by Moskaug et al. 2004)(Reference Moskaug, Carlsen, Myhrstad and Blomhoff68).

The effects of specific compounds in foods on gene expression are difficult to determine due to variable methods of tissue collection. Duration of fasting, perfusions of tissues if used, and the time of day of the sacrifice of the animals are rarely reported and have major influence on gene expression.

Human studies

Abahusian et al. (Reference Abahusian, Wright, Dickerson and Vol69) reported on the decreased amount of beta-carotene (but not retinol, and α-tocopherol) and increased urine and blood retinol binding protein in Saudi Arabia patients with diabetes. The reduction of BC correlated negatively with the glycemic control assessed by the fasting blood glucose(Reference Abahusian, Wright, Dickerson and Vol69). Also the other study from Queensland, Australia(Reference Coyne, Ibiebele and Baade70); Botnia Dietary Study(Reference Ylönen, Alfthan and Groop71), as well as the retrospective study of EPIC-Norfolk Studies(Reference Sargeant, Khaw and Bingham72) and the re-examined data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) demonstrated the negative association between the fruits and vegetable intake, serum carotenoids (β- and α-carotene, cryptoxanthin, lutein/zeaxanthin and lycopene) and insulin sensitivity(Reference Ford, Will, Bowman and Narayan73). However a recent prospective cohort study reported significant reduction of the 2 diabetes by higher intake of β-carotene, but not by other carotenoids(Reference Montonen, Knekt, Harkanen, Jarvinen, Heliovaara, Aromaa and Reunaner74). Also the other, nested case–control studies did not confirm the prospective association between baseline plasma lycopene, other carotenoids, flavonoids and flavonoid-rich foods with the risk of type 2 diabetes in middle-aged and older women(Reference Nettleton, Harnack, Scrafford, Mink, Barraj and Jacobs75, Reference Wang, Liu and Pradhan76). In line with these observations, is the negative outcome of clinical trial on the efficacy of the 12 year supplementation with β-carotene in preventing type 2 diabetes in the 21 476 US male physicians(Reference Liu, Ajani, Chae and Hennekens77).

In studies of type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome related risk factors the consumption of energy rich foods has been linked to the increased risk of developing these obesity and related diseases. Reduced risk has been associated with high consumption of apples and berries and increased consumption of fruits, vegetables and berries as a type of dietary habit(Reference Nettleton, Harnack, Scrafford, Mink, Barraj and Jacobs75). However, flavonoid intake or intake of flavonoid containing foods has not been found to be associated with decreased risk of type 2 diabetes, while consumption of red wine and other alcohol containing beverages appears to be associated with lower risk(Reference Nettleton, Harnack, Scrafford, Mink, Barraj and Jacobs75).

Conclusion

The metabolic changes in type 2 diabetes are complex and the process of the metabolic deregulation takes years to manifest in clinical disease. Therefore, any treatment strategy for prevention of obesity and type 2 diabetes is difficult and should utilize tools covering the spectra from basic molecular biology methods to clinical and epidemiological research to ascertain the _targeted and dosage-adjusted efficacy of the disease management.

Acknowledgements

The review was supported by the European Co-operation in the field of Scientific and Technical (COST) Research Action 926 “Impact of new technologies on the health benefits and safety of bioactive plant compounds” (2004–2008). Authors would like to express the gratitude for the excellent management of the project and inspiration made by Dr Jennifer Gee and Prof. Augustin Scalbert as well as gratitude to Docent Riitta Törrönen for making valuable comments and concluding remarks to the original manuscript. The authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.