.

With special acknowledgement to the late Alfred Kenneth Hamilton Jenkin and his book Mines and Miners of Cornwall, xv. Calstock, Callington and Launceston. Published in 1969 by Forge Books, Bracknell.

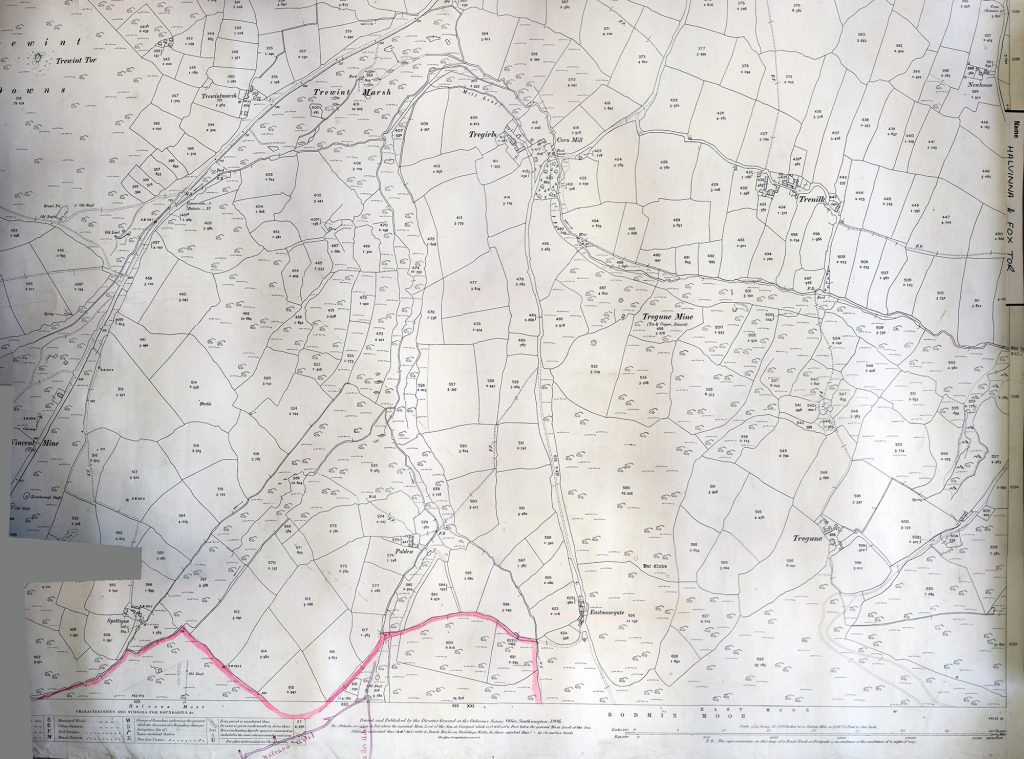

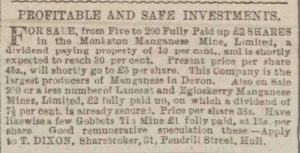

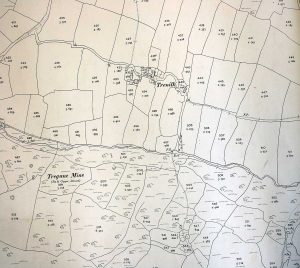

From the late 18th century and through the 19th century, many mining schemes were started all around Launceston, the most popular being the manganese mine at Lidcott, Laneast. Other notable mines were the Inney Consuls just above Two Bridges in the South Petherwin Parish (also known as the Two Bridges Mining Company) and just across the valley, the Trevell Silver Lead mine, in Lewannick parish. Down near the River Tamar, there were the Greystone silver-lead, Wheal Sophia, and North Tamar (started in 1839 and closed in 1857) mines which were to later form together and become Greystone Quarry. Over at Trewen by the Inney again we had the Trenault mine and limestone quarry and near Truscott, there was another manganese mine as well as another mine at Trebursye the opposite side of the Kensey Valley. Other mine workings in the area include Tredarrup, Treburtle and Trebullett.

In 1843 whilst sinking an artisan well in Broad Street, in the centre of Launceston, a large copper lode of “superior quality” was intersected at a depth of 200 ft. The enterprising family of Williams from Scorrier, near Redruth, immediately applied to the Launceston Corporation for a sett, but this was refused on the grounds that mining beneath the town would deprive the inhabitants of water by causing all the wells to run dry. Two years later five shares were offered for sale by George Carne of Plymouth in a mine called Wheal Launceston. (Mining journal May 13th, 1843 & March 1st, 1845). The site of the latter has not been identified but the historian, A.K. Hamilton Jenkin, in his 1969 book of ‘Mines and Miners of Cornwall XV,’ alluded that it may possibly relate to some old workings which were accidentally discovered during the Second World War when excavating a static water tank in the deep valley called Harpers Lake at the base of the old Willow Gardens.

Recapitulating his remembrances from the 1820’s, Richard Robbins observed: “There were the manganese mines of St. Stephens, paying wages to the amount of £500 per month, or £6,000 per year and the Lifton, Stowford, Sydenham, and Dippertown mines paying monthly £1,400 or £16,800 a year.”

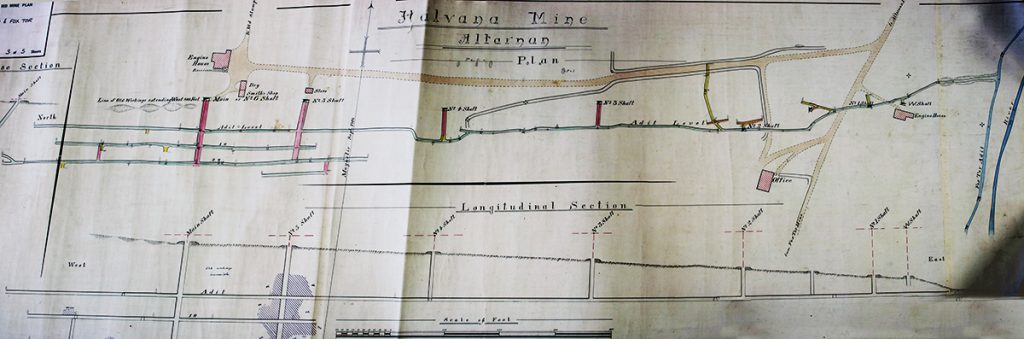

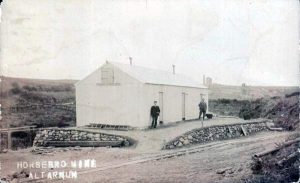

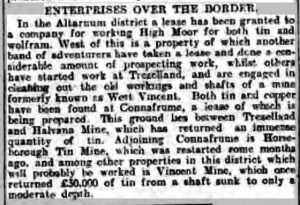

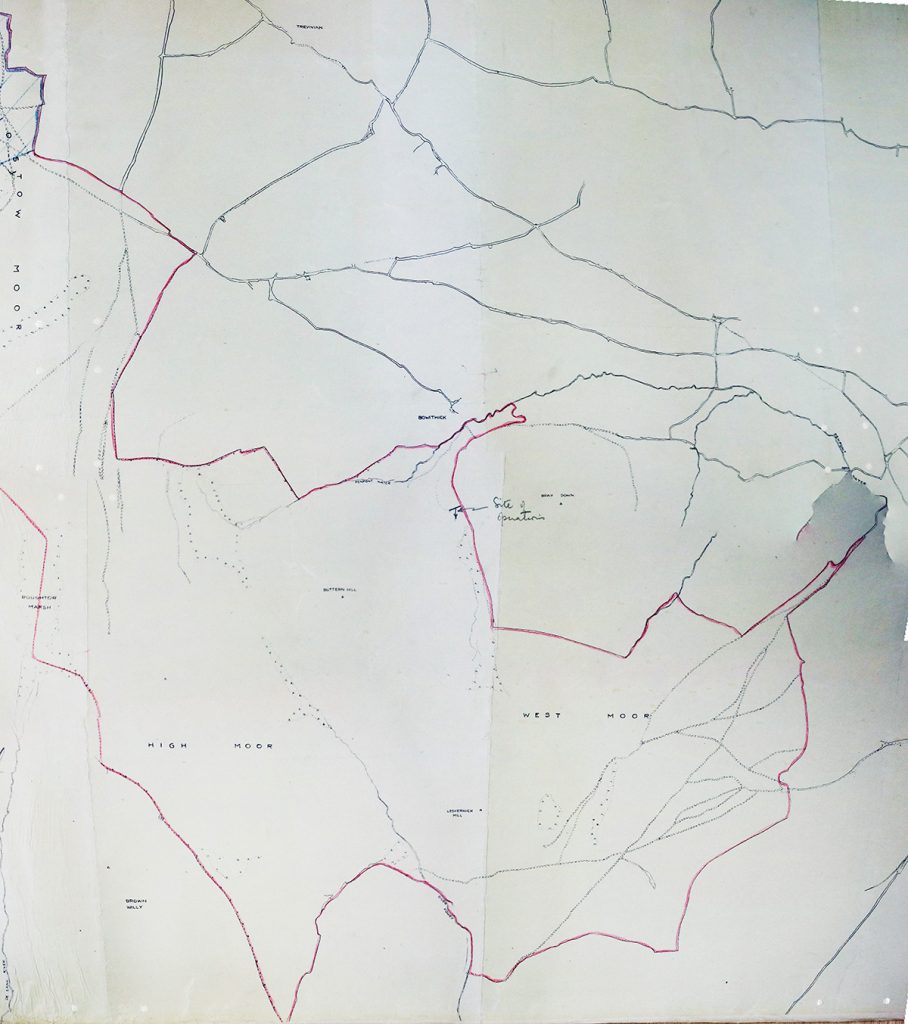

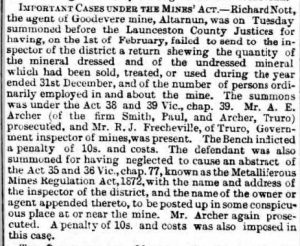

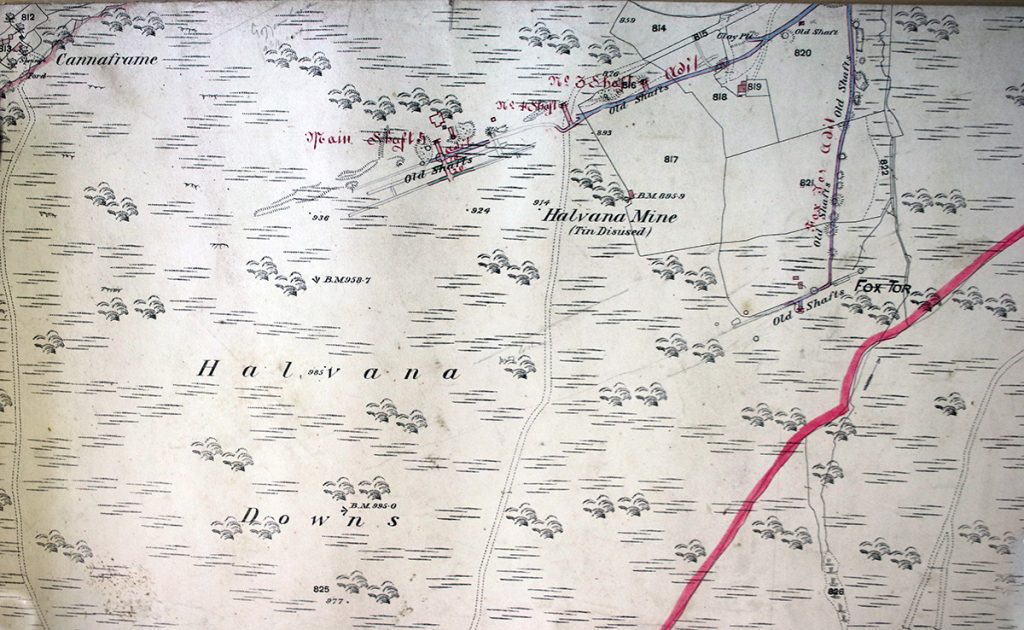

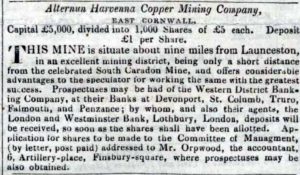

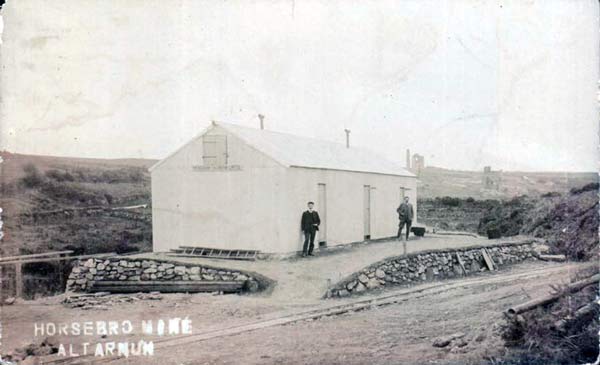

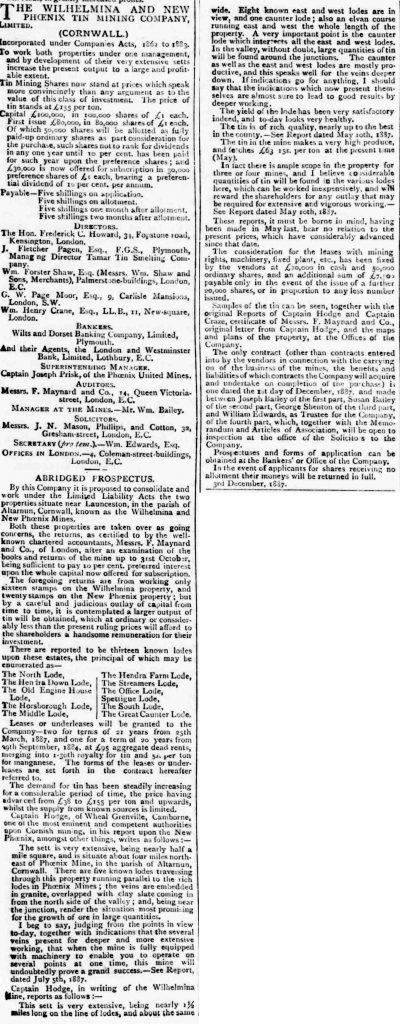

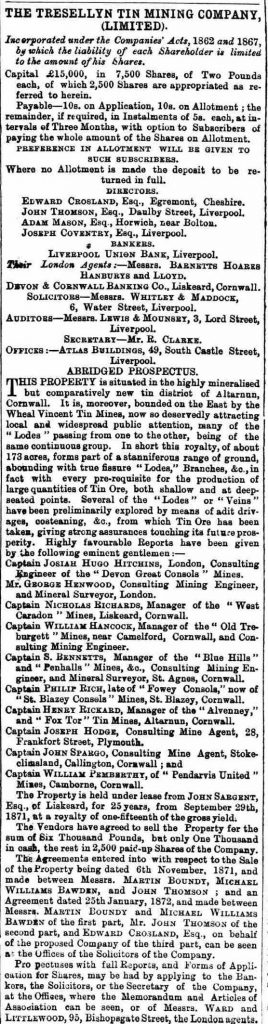

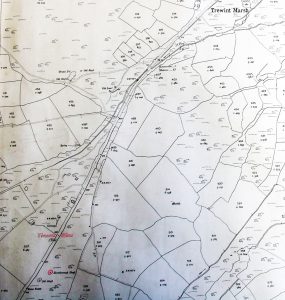

However, Altarnun proved to hold the most resources to be mined with mines scattered throughout the area. New Horse-borough (below left and right), Trewint United, Trezelland, Wheal Bray (closed in 1858) and Wheal Vincent (opened around 1871, closed in 1890 re-opened in 1900), were but a few and long after the mines in the other areas had ceased working and closed down, the mining of the Altarnun area continued apace.

At the beginning of the 20th century renewed vigour in the area brought about the re-opening of old mines such as Halvanna and West Vincent followed by Trezelland, Cannaframe and Horse-borough in 1907. This was not without consequences, as the rush to mine took little precaution in regard to the pollution of the waterways with the River Lynher soon becoming very polluted, a point not lost of Francis Rodd of Trebartha in his correspondence in the Western Morning News of March 17th, 1900, where he stated that he fully expected his part of the river to be void of all living animals due to “this little mine just outside of my property!”

This interest was short-lived and most of the mines eventually closed by the beginning of the First World War. However, one, Wheal Vincent, became a valuable prospect for the war effort in that it held a copious amount of wolfram. This wolfram, also known as tungsten, was invaluable as it was used in making steel and the tungsten alloys have also been used in cannon shells, grenades and missiles, to create supersonic shrapnel. The mine had struggled like all the others before the war, and even with an injection of £7,000, the syndicate leasing it, had to hand it back, whereby it was taken over by the Government in 1915. By 1917 the mine was employing up to 40 men. However, some doubt was raised on how productive Wheal Vincent actually was with an accusation that it produced little of the reported monthly 55 tons of mineral, stating that barely 3 tons would have been the more likely figure. But with the war over and having the backing from the Government removed, the mine finally closed in 1919, with all the equipment being sold at auction in the August of 1922.

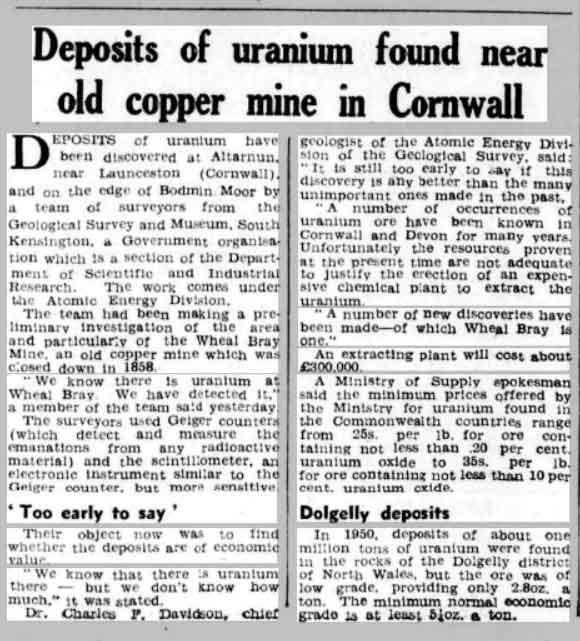

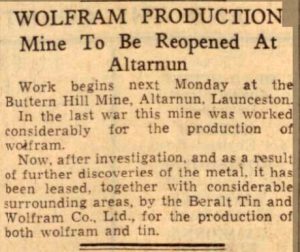

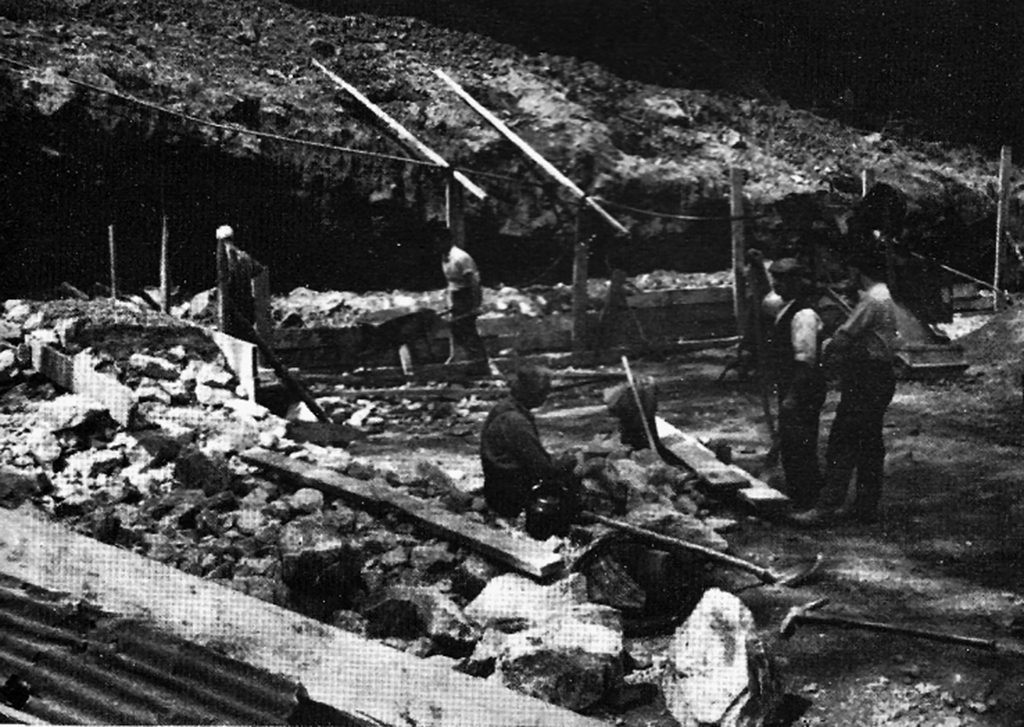

The last actual working mine was Altarnun’s Wolfram mine seen above being worked in 1938 and this closed in 1957, although in 1953 small deposits of uranium were found near the old Wheal Bray Mine, but being so small it was deemed uneconomical to mine.

Known Mines

Altarnun area

Altarnun Consols (closed in 1856)

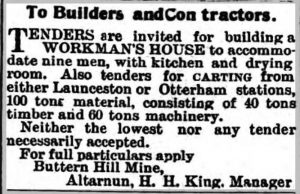

Buttern Hill Mine, near Bowithick

Buttern Hill was an open cast mine on Bodmin Moor near Bowithick. Wolfram and tin ores were extracted from the mine. A pump driven by a steam engine, delivered through canvas pipes to the mine for panning and washing. A dam was built for this at the edge of the Kenniton Marsh. To gain access to the mine, two well-constructed bridges were built over the small stream from the ford at Bowithick. The washed clean gravel became a useful material for making concrete to construct (the Blowing House) the early form of tin smelting house. The end product from this building was known as ‘grain tin.’ Furnace temperatures for the Blowing House were raised by bellows, although in most cases operated by a water wheel, a circular area around which a shaft was turned, suggest horses were also used. The fuel used was charcoal, demanding large quantities of wood. A large steam engine and crusher bases and conveyor systems supports still remain today. Some of the granite stone walls were still standing up to the 1960s, but have since fallen away. After the wolfram and tin ores were graded out, hundreds of tons of stone were supplied for road materials. During both the 1st and 2nd World Wars the mine was worked by German Prisoners of War, with the nearby farm of Bowithick being the site of the P.O.W. Camp.

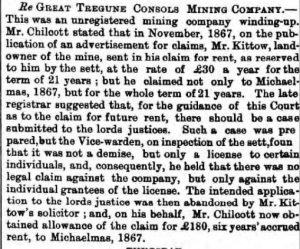

At Great Tregune Consols Mining Company meeting, on Thursday, the accounts showed a balance at bankers, 170 Z. 12s. 10d.

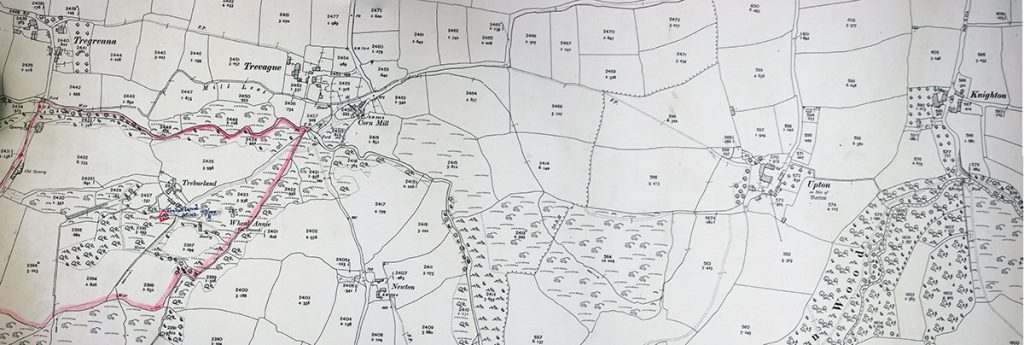

The old workings, which are of very small extent and shallow, are situated on the south side of the River Lynher about midway between the ruined corn mill of Trevague and Treburland homestead in the parish of Altarnun. The ‘Treburland Manganese Mine’ adjoined the footbridge over the river. Here, the ore occurred in small beds and pockets, in a country-rock consisting of killas altered by contact with the granite. The workings were very shallow, nowhere exceeding 25 feet, and were drained by a short adit driven in through the marshy ground from the river. At what date the deposit was discovered it is not known, but between the years 1887 and 1890 the mine produced 470 tons of manganese ore (pyrolusite) and was then worked in conjunction with the adjoining Treburland tin and wolfram mine and by the same adventurers. Although of no great economic importance, the ore-body was remarkable for its extraordinary assemblage of minerals, no less than 30 varieties having been identified and recorded by Sir Arthur Russell (Mineralogical Magazine, September 1946) during his frequent visits to the mine from 1906 until the Second World War. Little or nothing can be seen of the manganese workings to-day and the dumps to which Sir Arthur devoted such painstaking research have practically all been removed.

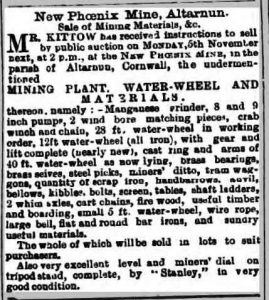

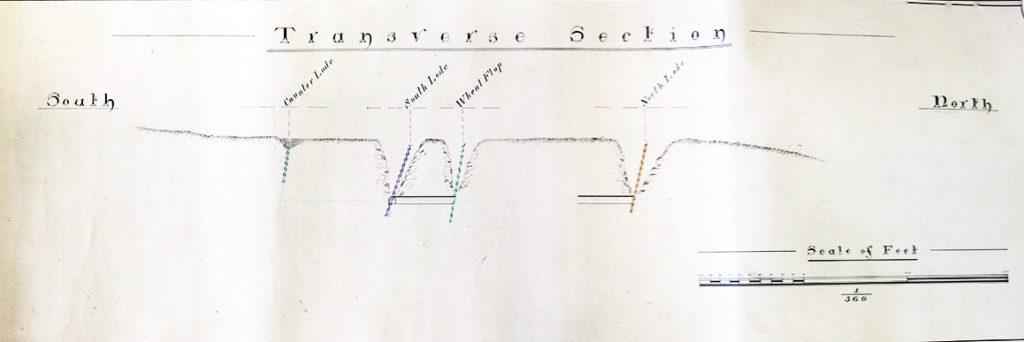

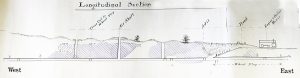

As stated, during its working in the 1880s, the manganese deposit was developed in combination with the ‘Wheal Annie‘ or ‘Wheal Flop’ tin and wolfram lodes and by the same adventurers. Owing to the supposedly uncomplimentary nature of the latter name, by which the tin mine was known to the miners, (in reality the name is probably commemorative of its having been originally drained by a flop-jack engine, which was a primitive pumping device, with a rocking beam), the name ‘New Phoenix’ was given to the joint concern by the manager, Captain Vercoe, and under this title sales of 37 tons of black tin were recorded in 1884 to 1890, (Geolog. Mem. Tavistock & Launceston pp.112,115). Later known simply as ‘Treburland Mine,’ the lodes were worked during the 1914 War, and again in the Second World War when some 2,000 tons of mixed tin and wolfram ore was raised from above the 50-foot level and treated at the ‘Prince of Wales’ mill near Gunnislake (Dines, pp. 585-6).

Close to the manganese workings are the ruins of a tin-stamping mill and in the walls of this are built blocks of rhodonite. The appearance of this mill suggests that it is of some antiquity and the water-wheel which drove it was fed with water by a leat, an underground portion of which appears to have traversed the manganese deposit; hence this may very well have been discovered during the construction of this watercourse. Most if not all of the dump material appears to have been raised during the 1887-1890 working.

Trezellern Tin Mine (Trezelland/Tresellyn started in 1872)

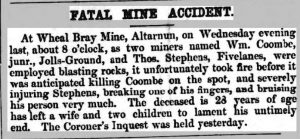

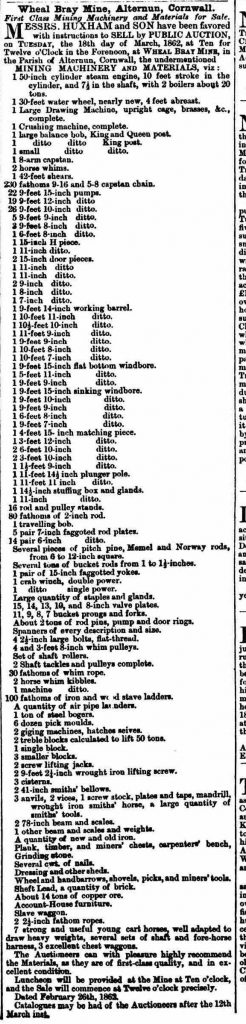

Wheal Bray Mine, Altarnun (closed in 1859)

An E.N.E. lode worked near the granite margin and followed into the killas. The lode had also been tested along the hilltop to the southwest but was poor. In 1857 and 1858 508 tons of copper ore were raised and 15 tons of copper. The veinstone was porous quartz. White mundic occurred in great quantity and the tip was being carted away to form garden paths, as it was poisonous to weeds.

Wheal Trewint Consols, Altarnun

Wheal Vincent Mine, Altarnun. Between 1872 and 1881 the mine produced 62 tons of black tin.

Broadwoodwidger

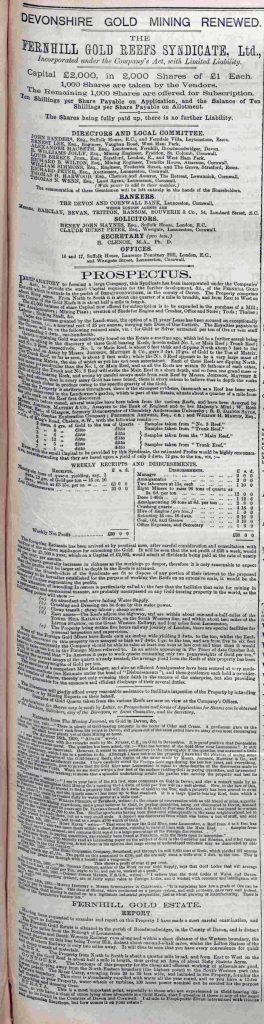

Fernhill Gold Mine

Egloskerry

Egloskerry manganese mine (c.1886)

Lezant

This small mine was situated four miles south-east of Launceston in the parish of Lezant and was worked from 1877 to 1880, when it produced about 150 tons of manganese ore (pyrolusite) valued at £150 It was reopened for a short time in 1907 when a little exploratory work was done, but no ore raised.

Larrick Ochre Mine.

A deposit of ochre at ‘Higher Larrick’ was developed during the 1880s by means of two shafts situated 500 yds. N.N.E of the farmhouse. The oxide of iron which gave rise to the ochre was formed by the decomposition of lava, in which several pits were sunk with the view of testing its extent and quality. At a depth of 45 feet tunnels were driven and the material extracted by the system of pillar and stall. Both these shafts are now filled but at ‘Lower Larrick’ traces of ochre pits are still visible, the output from the latter being treated in a shed near Trecarrell Corn Mill. Very little was worked. (Geolog. Mem., Tavistock & Launceston, p.p. 101, 115).

Greystone Wood Mine, North Wheal Tamar or Greystone silver-lead mine and Wheal Sophia.

In Greystone Wood adjoining the River Tamar, a deposit of manganese ore occurs in detached irregular pockets. These have been worked by a number of small shafts near the 400 ft. con-historic Camp. Between 1877 and 1880 production amounted to 150 tons (Sir Arthur Russell, Mineralogical Magazine, September 1946, p.230), working being subsequently renewed in the years preceding the First World War. The ore at that time was lowered down the hillside by a tramway connecting to the road, the winding drum with remnants of steel cable which operated the trucks being still ion the site in 1962. From the foot of the incline, the material was transported to Launceston at a cost of 2/6 per ton. In 1953 Mr Stephens formerly of Greystone Farm stated that he had often been employed in this work as a young man and that the ore was so heavy that it not infrequently broke the axle of the wagons. (Cyril Andrew, St. Austell in litt. 1953).

In the Geological Memoir, Tavistock and Launceston, the Greystone Wood Mine is also credited with having produced small quantities of galena, the writers having confused it with the quite distinct ‘Greystone Silver-Lead Mine’ which lies about 1,000 yards to the north. Here an engine house and ivy-covered stack were still standing in 1966 adjacent to the north side of the road leading west from Greystone Bridge, whilst across the road, on its southern side, were the burrows of two other shafts. The mine appears to have been first started in 1831 when a small company of adventurers, with the aid of a horse-engine, sank a shaft to 20 fathoms. At 11 fathoms depth, a level extended 70 fathoms on the lode was said to have opened up sufficient ground to produce 600 to 700 tons of lead ore. Below this, a 20-fathom level was driven 30 fathoms on a copper lode, 3 ft. wide and yielding “good work throughout.” This last lode lay three fathoms north of the lead lode but the two were expected to form a junction at a depth of 36 fathoms. Some 15 and 45 fathoms further north other lodes were known to exist. The more northerly of these were subsequently exploited in a separate sett named ‘Wheal Sophia’ (Mining Journal March 26th, 1853) whose main workings are probably indicated by the old shaft that was shown on the O.S. map in Longstone plantation which now sits north of Greystone Quarry.

In 1836 the Greystone or ‘Gresson’ mine at it is commonly pronounced locally, was re-granted under the name of ‘North Tamar’ and was stated by De la Beche to be raising “some of the purest sulphuret of zinc (blende) which we have seen. The ore which is found mixed with galena and bisulphuret of copper, is yellowish and abundant, though entirely cast aside and neglected at present. It probably contains little else than zinc and sulphur.” (Report on the Geology of Cornwall, Devon and West Somerset, 1839, p.616). In 1839 it was announced that the sett and machinery were to be sold as a going concern to the ‘Victoria Mining Company’ of Liverpool and the opportunity would be afforded to the North Tamar adventurers to become shareholders therein (Mining Journal August 3rd and 31st, 1839). It would appear, however, that nothing came of the proposal and so far as is known the property remained idle for the next fifteen years.

In the meantime, work was proceeding at ‘Wheal Sophia’ whose sett immediately adjoined the northern boundary of North Tamar. By December 1846 an adit, starting at river level, had been driven 40 fathoms on a south-underlaying copper lode, 6 to 9 ft. wide, which was expected to unite with the ‘Gresson’ north lode at a depth of 45 to 50 fathoms. A shaft had also been sunk 6 fathoms on the top of the hill but the water being ‘fast’, work here had been suspended. In April 1849 the mine was inspected by a Captain John Spargo who reported that the adit had then reached a length of 70 fathoms, with a winze sunk 12 fathoms below it. Although the lode at adit level had well-defined walls and was showing traces of yellow copper ore, malachite and mundic, the company was advised to discontinue work at this point and to concentrate on sinking an engine-shaft to take the lode at a deeper level – “beneath the uncongenial country the adit is driven in.” (Mining Journal April 21st, 1849). For some time after this, the mine appears to have languished and in February 1851, as a result of non-payment of calls, it was decided to suspend working. Operations were resumed about nine months later when the chairman reported that the whim had been repaired, the shaft timbered down and divided, whilst a wheel was being erected capable of draining the mine to 60 fathoms below adit, in addition to driving a crusher and drawing machine. A leat had recently been started to bring water to the wheel from a point above Greystone Bridge but owing to severe floods which had caused the Tamar to rise eleven feet above its ordinary level, the sinking of the wheel-pit had been delayed (Mining Journal January 31st, 1852).

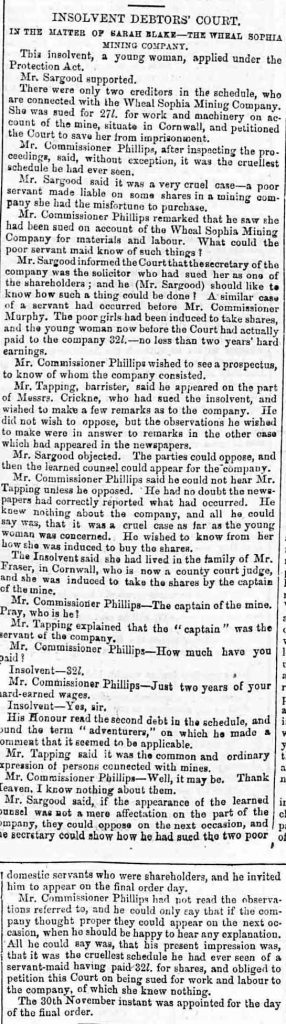

In the course of the following summer, Wheal Sophia made history by being the first Cornish mine ever to detonate a blasting charge by electricity. Under the supervision of Mr C. S. Richardson, the engineer, a galvanic battery was placed in the count-house, and a “rock shot at grass with a wire 300 ft. in length.” A quantity of powder was then put in a cartridge and exploded two feet underwater, and finally, a hole was charged about 40 fathoms up the adit and connected to the battery at the surface. “The instant the wire was attached a tremendous explosion took place.” The engineer claimed that in this way a hundred holes could be fired daily, with perfect safety for the miner and at a much less cost than employing fuse (Mining Journal August 21st, 1852). By December 1853, however, the mine was in difficulties, the bottoms being then underwater. Although a steam engine was acquired with a view to carrying out some further trials these were apparently unsatisfactory, and in September 1854 the sett and machinery were advertised for sale in the Mining Journal. The last, sad, reference to the mine concerns a servant girl, Ann Sirngour, whose case was heard in the Insolvent Debtor’s Court. The petitioner, it appeared, had been induced in 1845 to take up two shares in the mine for which she had paid out her life savings the sum of £29 12s. Subsequently “calls” had been made upon her for £9 10s., added to which she had been sued for £35 19s. in respect of machinery supplied to the company. In the composition for these debts, she offered to pay £6 out of her wages, but this had been refused. The Commissioner very properly ruled that the case was one for ‘Protection’ and thus saved her from the fate of a debtor’s prison, (Mining Journal July 22nd, 1854) although at a loss of practically everything she possessed.

In the year which witnessed the demise of Wheal Sophia, proposals were made for re-starting the Greystone Mine (North Tamar). A fresh lease had been recently obtained by Messrs Offord, and a Captain Henry Luke appointed manager. On examining the lode in the shallow adit a branch of lead was found 12 inches wide and preparations were being made to erect a steam engine (Mining Journal May 12, 1855). Operations continued until 1861, the sett being referred to by Spargo in 1868 as “idle seven years.” This, however, was not the last to be heard of the mine. In 1877, under the heading ‘Greystone Silver-Lead Mine,’ tenders were invited for the supply of a second-hand 40″ pumping engine, 40 fathoms of pit-work and ladders, and a horse whim. Six months later further estimates were sought for building an engine and boiler house, together with the loading for a fly-wheel, the contractor being required “to take down the Old Engine House and Boiler House now standing on the mine” (Mining Journal May 19th, 1877). In this final working, the sett appears to have included part of the former Wheal Sophia, reference being made to it in 1880 under the title of ‘Greystone and East Longstone Mines (Mining Journal 1880, vol. 1, p. 260).

1856 directory entry for North Tamar Mine: The mine is in the parish of Lezant, the union of Launceston, hundred of East, Cornwall. It is situated 4 miles from the market town of Launceston, 7 from Callington, 21 from Plymouth, and 268 From London. The nearest shipping place is at Cotehele quay, on the river Tamar, which is 111 miles from the mine. The mine was worked some years since under the name of Gresson Bridge Mine but is now worked under the name of North Tamar Mine, by Henry Luke and others. The mine was held under a lease for 21 years, from Christmas, 1853, and granted by Mr Symons, of Lezant. One engine-shaft has been sunk 20 fathoms deep; two crosscuts are driven east. There are five lodes running through the sett: four of them are lead lodes, and three dipping west, and one dipping east, 3 feet 6 inches in a fathom. There is also an east and west copper lode crossing the lead lodes, and a cross course running north and south, which crosses all the lodes. A steam-engine for the purpose of working the mine was erected in 1856. The country is blue slate, dipping both east and west. The nearest granite is at Kit Hill, 7 miles distant. The mine was divided into 4,096 shares, upon which 16s. per share was been paid. The agent and manager was Henry Luke, of Lawhitton, Launceston.

Trebullet Hill Mine.

In 1881 the finding was announced of an antimony lode on Trebullet Farm, about 1,110 yds. west of Lezant Church. Near the surface, the lode was two feet wide and from a depth of only three fathoms, 12 cwt. of high-grade ore was recovered. (Mining Journal, October 8th, 1881). Under the name of ‘Trebullet Hill Mine‘ a shaft, drained by a small portable engine, was sunk to a 9-fathom level which was driven 15 fathoms south and yielded 4 tons of similar quality ore. Reporting on the property in 1889 when working was about to be resumed, Captain Josiah Thomas stated that the lode ran N. – S. and underlay west, its productive part being nine inches wide and lying in clay-slate ‘of a favourable kind.’ The lode was increasing in size as it went down and he accordingly recommended deepening the shaft and extending levels southward into the rising ground. (Report at Tehidy Minerals Office, Camborne). From this working, an output of 10 tons of 43% antimony ore was recorded in 1891. (Geolog. Mem. Tavistock & Launceston p.116). A subsequent report by Captain S. Mayne, dated October 17th 1900 states that the lode had been proved for a length of 150 fathoms and by means of three shafts. South Shaft had been sunk to 14 fathoms and at a depth of 10 fathoms, a cross-cut driven east and west intersected a lode of ‘superior antimony’ 2 ft. wide. Middle Shaft, 105 fathoms to the north, was of similar depth and 36 ft feet a level passed through six branches which were thought to be ‘feeders’ of the main lode. North Shaft, 45 fathoms north of Middle Shaft had been sunk 10 fathoms on the lode and here a cross-cut driven six fathoms west also showed a number of rich branches. The mine at this date was equipped with an engine-house, pulleys and stands, balance bobs and a headgear, but does not appear to have re-started. (Doidge Papers Cornwall Records Office). Specimens of stibnite may still be found in the dumps, “the mineral being either in bladed masses intergrown with reddish-brown blende … or in the form of needles in a yellowish-brown blende ferruginous dolomite or ankerite.” (Sir Arthur Russell, An account of of the Antimony Mines of Great Britain). Close to this last, a parallel lode (or branch) of antimony was discovered in 1868 when cutting a drain on Trenute farm.

No work was done on this until 1908 when a shaft was sunk to a shallow depth from which a small amount of stibnite was raised. Working of ‘Trenute Mine’ was resumed in 1915, the shaft at that time being 30 feet deep and “much encumbered with water.” The lode varied in width from 3 to 5 feet and in addition to stibnite contained large quantities of pyrite, together with smaller amounts of arsenopyrite and blende. After working had ceased, a portion of the dumps was utilised for making up the entrance road to the farmyard. (Sir Arthur Russell). This source which has provided many excellent specimens of the ore is no longer available, the road having been surfaced with concrete.

Kensey Valley (St. Stephens and St. Thomas parishes)

Athill mine.

In a meadow on Athill farm a mile south of Egloskerry, an old adit-level now completely blocked and with no dump, which was, however, evidently driven for manganese. Interestingly in the Priory Rental Roll of 14 Edward IV (A.D. 1474) included:

ATTELDOUNE, Atledown, ATTEWELL, Attway, ATTELL, Attle, ATTEWODE, Attwood, ATTEWEY. Attle is a Cornish term for old mine workings or waste rock of no value, which indicates that the land in this area of the Kensey Valley had been worked in ancient times.

St. Stephens Manganese Company.

About one-mile north-west of Launceston mining operations were re-started in 1875 by the ‘St. Stephens Manganese Company‘ which was registered in Truro during that year with a capital of 5,000 £5 shares (Justin Brooke in litt). The workings are said to have lain in a field on the west side of the road leading down to Barricadoes Wood on the way to Yeolmbridge. No particulars of the deposit or the extent of its development seem to have been recorded and certain documents relating to the company, are now preserved in Lawrence House Museum.

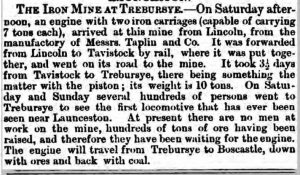

Trebursye Mine (Iron ore opened around the late 1850s)From 1862, a steam-powered traction engine was used to bring manganese ore 3 times a week from the Trebursye mine near Launceston to the manganese mill in Boscastle, and return with coal from the harbour.

Taken from the excellent ‘History of Boscastle and Trevalga’ by Francis Allen Burnard and edited by Andrew Ross M.A.

‘It was built by a firm called Taplin’s of Lincoln and was brought to Tavistock by rail, where it was assembled and brought by road to Launceston. Due to piston trouble, the road journey took three and a half days. It arrived at Trebursye mine on Saturday afternoon and on that day and Sunday it was visited by hundreds of people who came out of great curiosity. The engine drew two iron trucks capable of carrying ten tons each. The front wheels were five feet high and the back wheels eight feet, the width of the wheels twelve to fourteen inches. The work of the mine was suspended for a while, waiting for the arrival of the engine to take a quantity of ore to Boscastle, where it would eventually be taken away by ships. On its return journey, it had to bring coals. The engine’s first journey was to Boscastle, where it arrived on a Friday, but carried no ore on that trip. Progress was slow, due to the disordered state of the Machinery. The engine was brought back to Trebursye and appears to have been laid up for repairs for several months. On August the 20th it was again put on the road with 14 tons of ore in two wagons for Boscastle for shipment. On its return journey it left Boscastle with nine tons of coal, a crowd of people were present to witness the departure. It started successfully and went up the hill out of the village slowly and steadily. After it had gone a few miles, something happened; one of the wheels seemed to slide into the side of the road. The men in charge were able to remedy the fault and progress was made again, but not for long. This time there was a fault in the machinery and the engine had to remain on the roadside for a considerable time. Contact had to be made with the engineers and the engine was on the road again in the middle of October. It regularly made three trips a week to Boscastle with 20 tons of ore, returning with a quantity of coal. The engine was not at all popular with the general public, as it did not seem to be suitable for the roads of those days. The surface of the roads was not hard enough for such a mass of iron, the weight and the number of journeys. The people in the village called it a “mass of iron” or “a monster”. It had broken up a great number of the coverings of the watercourses, which were just thick stones and not at all suitable for such a mass of machinery. By its frequent breakdowns, it often blocked the roads, and it was very difficult to pass with any horses especially if they were at all spirited. Sparks and clouds of black smoke came from its funnel or chimney, which was a risk to stacks of corn and hay, hedges were set on fire and there was also a report that a man from St Juliot had his shirt caught on fire, In brief, the engine was considered to be a nuisance and it was named “The Juggernaut” by the locals.’

Higher Truscott Manganese Mine (Wheal Truscott) and Old Atway Manganese Mine

Manganese, in the form of pyrolusite, was extensively worked close to the hamlet of Higher Truscott in the early part of the 19th century, and in more recent times returns of manganese ore from here are given under the heading of St. Stephens by Launceston. Copper trials long preceded the exploitation of the manganese which, indeed, is said to have been almost unknown in this neighbourhood before 1815 (Symons, Gazetter of Cornwall, p233). By contrast with this, a copper sett at Higher Truscott was granted by one Edward Herle (sic) to George Kingdon in 1718, whilst a clause in the deed forbidding the destruction of “any shafts belonging to the said work” (Lawrence papers C.R.O.) shows that underground mining had taken place here even before that date. As ‘Wheal Truscott’ the property was being worked on a limited scale in 1844, and again in 1865 when Thomas Spargo, unaware of its past history, stated it as being a “young mine” which might well become “the nucleus of a group of mine’s in that unexplored area.” An adit was then being driven across the run of loads, one of which showed samples “so rich in copper as already to raise the shares to a premium on the market” (Mines of Cornwall and Devon, 1865). By 1866 a shaft had been sunk to 14 fathoms, and several tons of high-grade ore raised. The lode at this depth was 5 ft. wide and in the course of the following year the adit end reached a point where it was 20 fathoms below the surface (Mining Journal March 17th, 1866; Spargo 1868). The last working appears to have taken place in 1876-7 when the Geological Memoir records an output of 540 tons of brown haematite, of which 400 tons contained 15% of manganese. This so-called brown haematite was probably magnetite.

The site of the Higher Truscott Mine was shown on the O.S. map 16 N.E. as a quarry-like excavation on the north bank of the River Kensy, 800 yards west of Newchurches farm. This location is now thought to be incorrect since no manganese ore has been observed here, whilst traces of an adit formerly visible at the excavation’s northern end probably served to drain the great Cannapark limestone quarry which lies adjoining (During the early 1960s, the adit became choked and Cannapark Quarry presented a somewhat eerie spectacle in 1967, with dead trees emerging above the surface of the dark, forbidding water). The manganese workings, as identified by Sir Arthur Russell, lay directly north-east of Higher Truscott “where” he writes in 1944, “recent ploughing up of the pasture field nearest the hamlet” (During the Second World War, virgin pasture land was ploughed up to grow quota crops) showed depressions in the ground caused by mining. Around these lay considerable quantities of pyrolusite with quartz, a fact which was also observed in 1966 by A. K. Hamilton-Jenkin, when stones of ore of this description were to be seen in this field and the adjoining hedges. From here the manganese deposit extended in a north-easterly direction to the northern end of Cannapark Wood where traces of old dumps containing magnetite with pyrite are still visible (Sir Arthur Russell, Mineralogical Magazine, September 1946, p.229).

Immediately north of these on Atway Farm, in an enclosure then known as ‘Mine Field’ adjoining the farmhouse, could be seen a shaft and two pits, whilst further subsidences were still taking place around them (Per Mr F. J. Harris of Atway who adds in 1969 “the damage to the ground around is getting bad and it is now almost too rough to put a tractor and mower over it”). These workings mark the site of the celebrated ‘Old Atway Manganese Mine‘ where according to a correspondent in the Mining Journal of 1877 “large fortunes were formerly made, and an immense deposit is known to exist, by the evidence of several trustworthy persons who worked at the mine till it was suspended.”

About half a mile to the north-west, the same writer found other deposits of manganese then being worked near Langore. Here he writes “I came to the mouth of an adit, at the bottom of a hill, which I was invited to explore by one of the miners. I traversed this for about 120 fathoms, at the end of which I found opened up a large body of manganese, apparently free from any iron and likely to prove of great extent and easily workable. Almost adjoining this but on the other side of the road, I descended a short ladder and entered a large cavity diverging in several directions, and in each discovered deposits of manganese and manganiferous iron. Of the latter there appears to be an immense quantity, containing about 10 or 15% of manganese, and 51 to 60% of iron, besides some containing manganese up to 40%. Of the latter, there were then on the surface upwards of 150 tons, and also about 200 tons of the lower class. These mines belong to some gentlemen of Tavistock who have been working them quietly for the last three years but are now wanting more capital to employ additional labour and develop them on a large scale” (Letter signed ‘G’, Mining Journal Supplement, November 3rd, 1877).

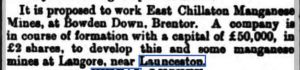

East Chillaton and Atway Manganese and Felstone Company.

In 1880 the East Chillaton and Atway Manganese and Felstone Company were formed with a capital of £50,000, for the working of Bowden Hill and Bowden Down manganese mines in the Devon parish of Brentor, together with ‘Langore and the celebrated Wayy (sic) mines near Launceston.’ At the Wayy Mine (which appears to have been a local corruption of Atway) it was stated that an engine would be required in order to ‘construct’ a shaft, the latter being intended to connect with a deep adit which would eventually serve to drain the mine and afford an ‘exit for the ore.’ The bed of felstone was said to be suitable for the production of vitrified blue bricks, white enamel bricks and terra cotta work. It appears, however, that little was done by this company which went into liquidation in August 1883, (Mining Journal, March 5th, 1881; Stock Exchange Year Book,1883) with no recorded output.

At the eastern end of Langore, adjacent to ‘The Green,’ subsidences were still being experienced in 1967 and were traceable on the back of an adit which extends to this point into the rising ground on the south. An adjoining well, shown on the O.S. map 16 N.E., and thought to have been the adit mouth, served until the 1960s as the local water supply. About 350 yards to the west, water still flows from another south-driven adit which opens beside a farm lane directly across the valley from Langore’s western end. Neither of these adits is known to have been worked within living memory of the 1960s, but in 1967 Mr Dawe of Langore recalled to A. K. Hamilton-Jenkin that his mother, when a little girl, had been through one of them.

Lawhitton

Lawhitton Consols Mine.

A quarter of a mile north-east of Lawhitton Barton, an old shaft shown on the O.S. map 17 S.W. indicates the site of ‘Lawhitton Consols.’ The sett was a large one and said to contain four east-west lodes, in addition to an elvan course. By 1860 the principal lode had been opening up in a number of shallow pits where it showed widths of 2 1/2 to 4 ft. and consisted of quartz and mundic, with stones of copper and lead ore. In order to test its value at greater depth an adit, starting near the stream, was driven southward into the rising ground where it was expected to cut the lode at about 10 fathoms from the surface (Thomas Gregory, Mining Journal, October 13th, 1860) whilst no further reports seem to have been issued, the mine was listed in Robert Hunt’s Mineral Statistics from 1860 to 1863, although shown in the two latter years as ‘suspended.’ Evidence of its working still remained in 1966 in the form of a long, slatey burrow adjoining the stream, near which traces of another adit appear to be visible in the steep-sided northern bank.

Lewannick

Trevell Mine. (Trevell Silver Lead Mine)

1 1/4 miles westward of Lewannick, an N-S lead lode has been worked by the side of Penpont Water. Operations had been started by February 1850 when an adit was being driven south on the lode which was stated to be 8 to 12 ft. in width. During the following month Captain Jehu Hitchens of Tavistock reported that the adit had reached a length of 50 fathoms and an N.W.-S.E. caunter, from which stones had been taken yielded 10½ to 12½ in 20 for lead and 33 ounces of silver to the ton, was likely to form a junction with the main lode in depth. He accordingly advised sinking a shaft and driving a level at 10 or 15 fathoms below the valley bottom, sufficient water-power being available from the nearby river to render such an undertaking independent of steam (Mining Journal, February 16th & March 30th, 1850). In the course of the next six months a 20 x 5 ft. pumping wheel was erected on the ‘tension principle,’ and by the following May a leat had been excavated for 700 fathoms with a view to obtaining additional water from the River Inney. In October 1851 the lode in the 22 fathom level, south, was stated to be ‘orey’ and stones of lead and black jack (blende) had been broken. The ground consisted of a soft, white elvan in which the water was very quick and troublesome. Despite this, the shaft was down to a 32 fathom level by the end of the year, and driving was in progress north and south on the lode which was 6 ft. wide and composed of quartz, fluor-spar, mundic and galena. From the 22 level, a cross-cut was being put out in search of another lode or lodes believed to be standing to the west (Mining Journal, October 11th & December 6th, 1851).

Up to this time, no ore appears to have been returned and on April 17th, 1852, the materials consisting of the wheel, an air machine, 70 fathoms of air pipes and a horse-whim were advertised for sale in the Mining Journal. Although no mention of the mine is made by Collins, Dines or the Geological Memoir, a search by A. K. Hamilton-Jenkin in 1958 revealed the shaft, adit wheel-pit and leat just as the old men had left them a hundred years before. So secluded was the site, however, in the woods beside the river that even the farmer of Trevell was unaware of their existence.

Trelaske Mine (manganese) a small quantity of this semi-metal was raised. It had a regular lode about ten fathoms from the surface.

Lifton

A manganese mine (c.1815) along with two limestone quarries.

North Hill

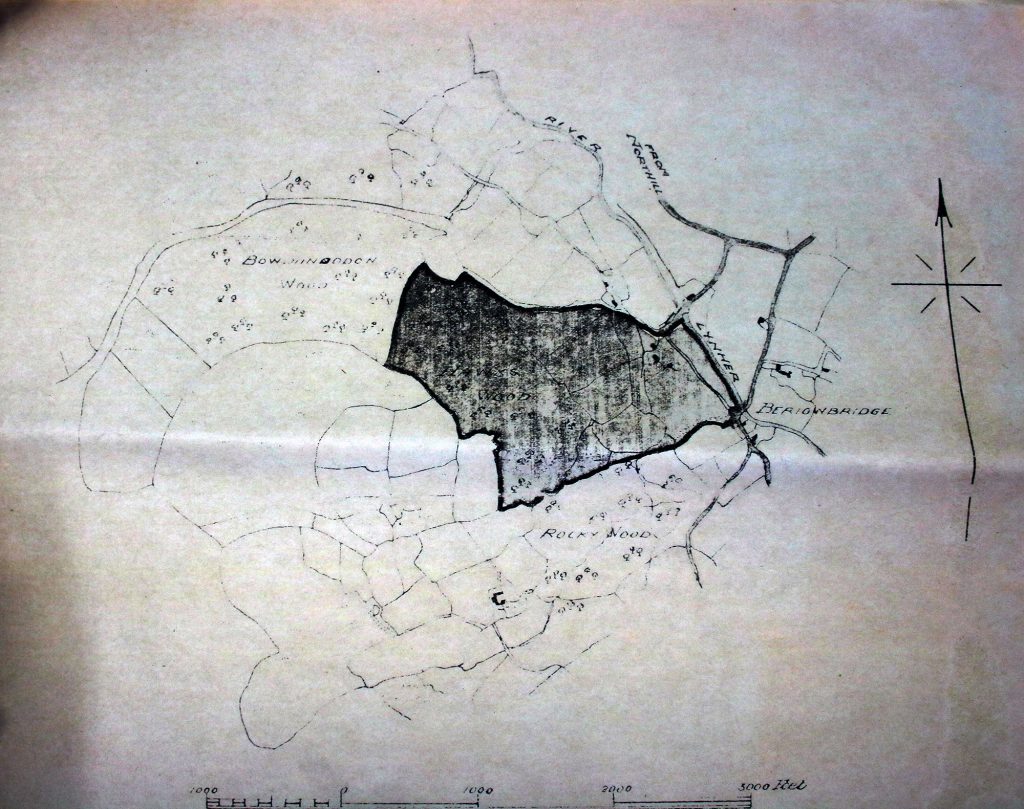

Berriow Consols Mine (1853-1860) Copper Mine.

Bodmin Moor East Tin Mine

Caradon & Phoenix Consoles Mixed Mine

Great Rodd Mixed Mine This mine along with Wheal Rodd is situated just above Bathpool. A short distance north of the village, a lead lode outcrops in the steep-sided valley close to Uphill Farm. To develop this a company was formed in 1878 bearing the title of Great Wheal Rodd and with a capital of £12,000. A report in the Mining Journal of March 30th in that year states that a deep adit level, taken up from the stream, had been driven 28 fathoms and was expected to cut the lode in about three week’s time. Budge’s Shaft which had been sunk to 12 fathoms would then be unwatered and the adit continued on the lode where, going west, it would gain backs of more than 30 fathoms. In the course of the next two months, it was announced that the lode in the deep adit was 6 feet wide, carrying two regular walls and composed of quartz, prian and silver-lead. A large quantity of ore-stuff was standing at the surface near the mouth of the shaft and as driving on the lode proceeded into the hill towards the junction with another lode its appearance “vastly improves.” On this optimistic note, the history of the mine ends. Its site, however, in 1965 was still showing an open adit and traces of a ventilation shaft.

Halwell Ochre Pit Mixed Mine

On the south side of the River Inny, a deposit of ochre has been exploited in the Halwell Quarry, 770 yards N.E. of Lenoy Farm. This, like the other workings at Larrick on the opposite side of the river, operated intermittently whenever the price rendered it profitable, the last occasion being in 1957. According to Dines (p. 589)(Detailed mining information for mining in Devon and Cornwall gathered by George Dines (former BGS Geologist) for a period around 1921. Maps, plans and accompanying notes and documents provide detailed information on the metal mining ( mainly tin, copper, lead) at that time. A synthesis of this information was published in “The metalliferous mining region of south-west England” 3rd impression 1988), ochre was first produced at Halwell in 1920 but there is reason to believe that it may have been known at a much earlier period. In Halwell Wood, adjoining the former fish pond, an old man’s adit, showing traces of iron ore, has been driven eastward for a reputed length of a quarter of a mile, a distance which would certainly have carried it through and beyond the site of the ochre bed. In 1954 the adit figured in the news when a bullock forced its way into the end. After three days of exhausting labour by twenty-four men, working in relays, the beast was eventually dragged out backwards, apparently none the worse for wear (Western Morning News, July 7th, 1954).

Wheal Lanoy.

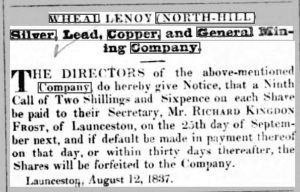

Half a mile to the north, in a tributary valley which joins the Inny near Ruse’s Mill, trials were started in 1836 by the Wheal Lanoy (North Hill) Silver, Lead, Copper and General Mining Company. An adit was commenced at the eastern end of the sett and on driving about 70 fathoms a N.-S. lode was intersected, three feet wide and yielding small quantities of galena. Eight fathoms further west a copper lode was encountered, carrying with it, as the Captain reported, “One of the prettiest north walls I even saw, as smooth as glass.” On this Pethick’s shaft was sunk to adit level where in the course of a few fathoms driving the lode opened out to six feet in width and was composed of mundic, zinc, lead and “hundreds of small cubes of yellow copper ore.” Near this point, Archer’s shaft was put down to a depth of 15 fathoms (11 fathoms below adit), the water being drained by a 25 ft. diameter wheel. After a trial lasting two years, and an expenditure of £2,000, the venture was finally abandoned in 1838, with no recorded output (Mining Journal, 1836-38).

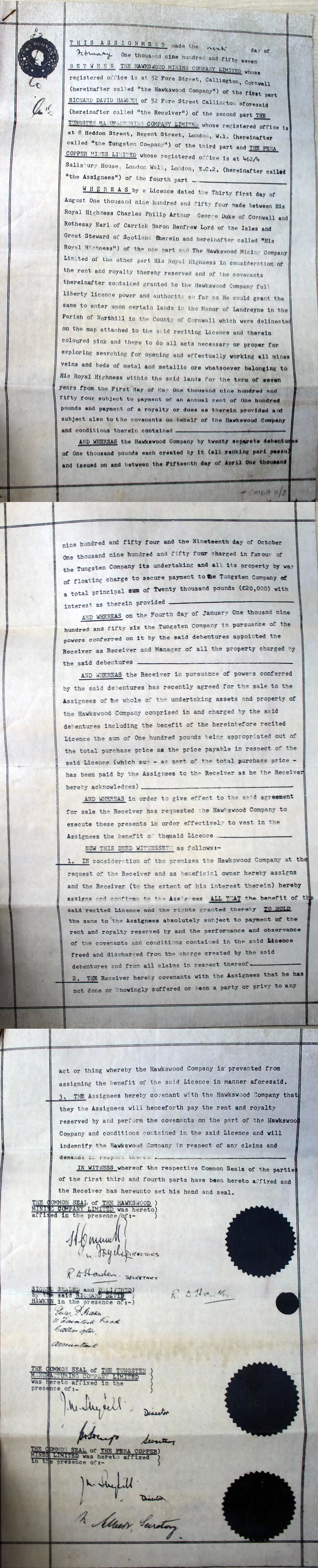

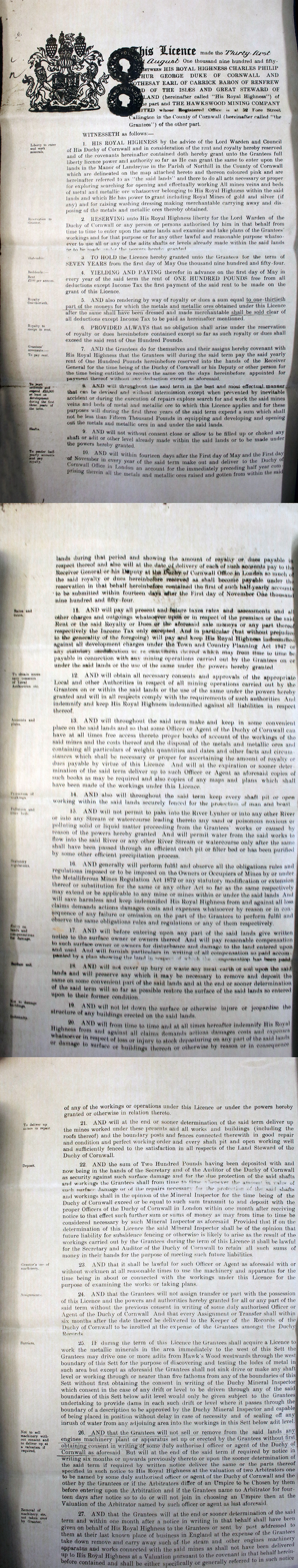

North Hill History Group Hawkswood Mine

Kingbear Mixed Mine

Middlewood Mixed Mine

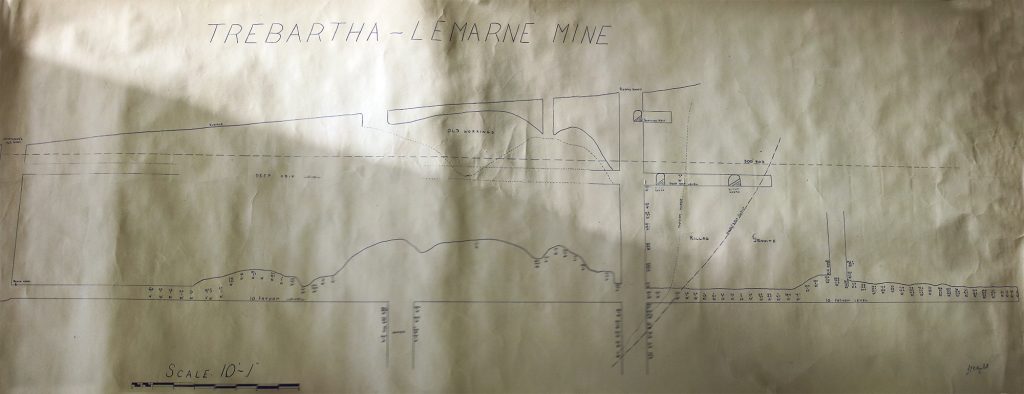

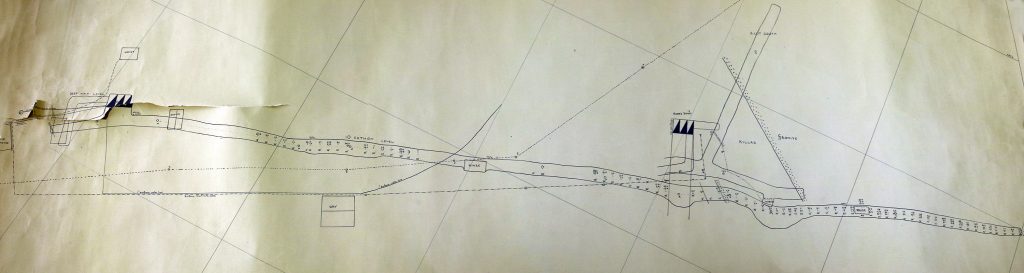

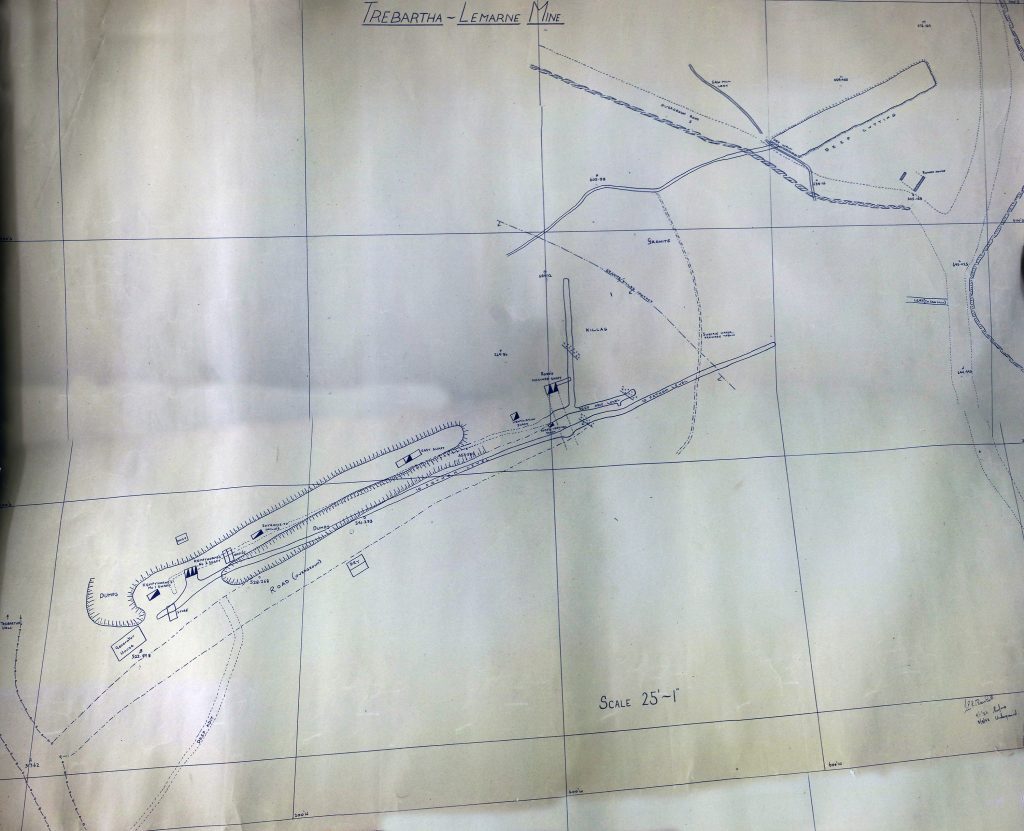

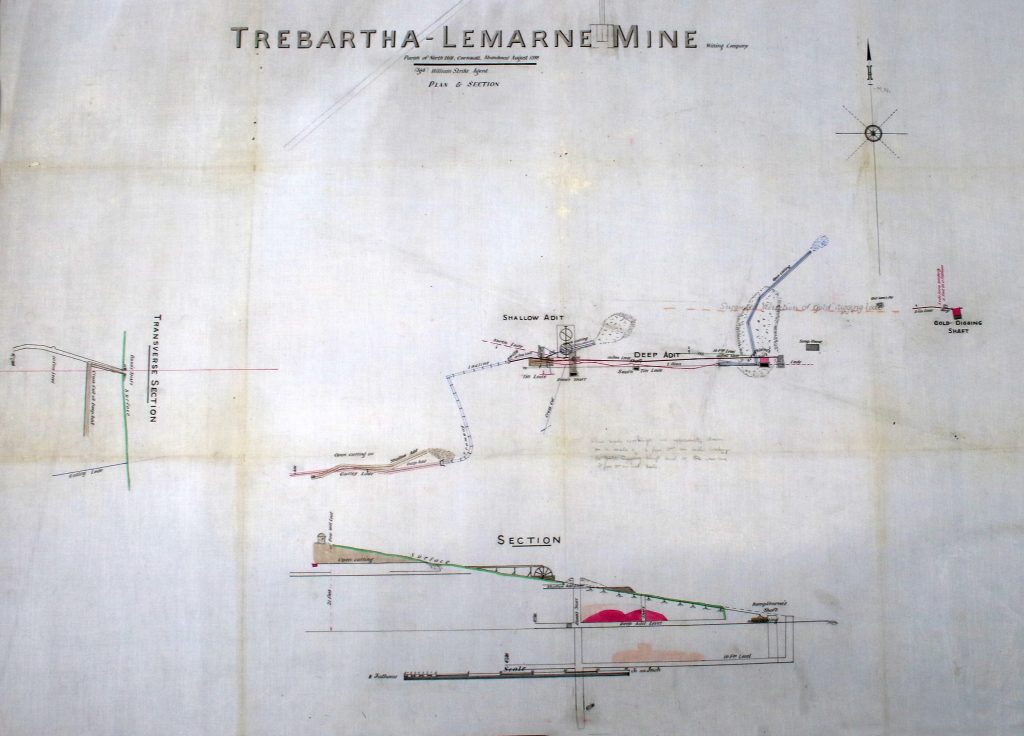

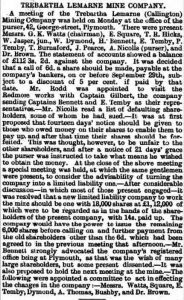

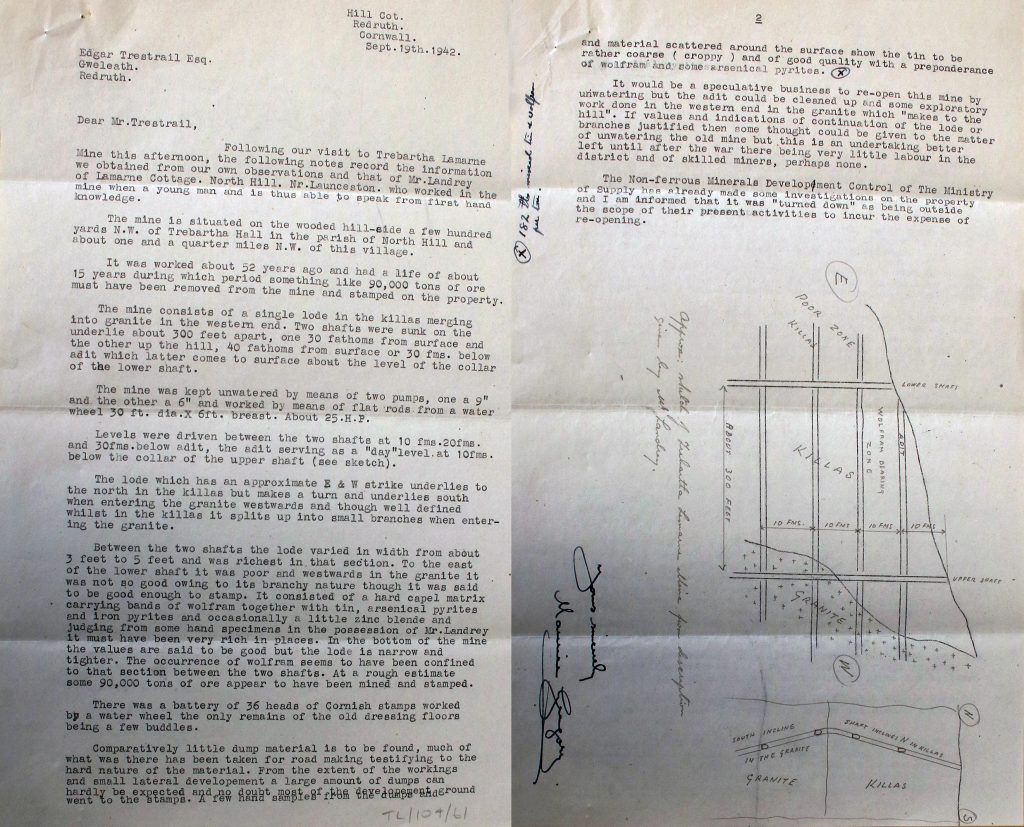

Trebartha Lemarne Mine

At what period its lodes were first discovered is shrouded in the mists of time, but Trebartha Lemarne is known to have been active in the 16th century when it was in the possession of a certain Henry Spoure, to whose family the estate had descended through marriage with the Trebartha’s of still more ancient lineage. So much tin was raised at this time that on his death Mr Spoure was able to leave £1,000 to each of his five daughters, being “the first thousand pounds ever given to a daughter by any private gentleman of his quality in Cornwall.” Small quantities of gold were also disseminated in the lodes and from this, a ring was made. Authority for these statements is found in a quaintly-worded MS poem composed by a descendent, Edward Spoure, in 1694. In this, he relates the history of the family and their estate. (Partial transcript at R.I.C. of the original MS formerly at Trebartha Hall).

“there’s also Tin, Mondick and Copper Store

And other precious valubale ore,

to prove this truth witness my old seal ring.

I’m sure it may be gott

I wish it were my lot

Troth it would make me then carowse and sing,

full 5 descents this old gold ring has been

possest since first extracted from the tin

by th’ Spoures, so by succession now is come

to me of the first line now the last son.

then let’s begin and dig, nere doubt of small things,

leave the success to Him that governs all things.”

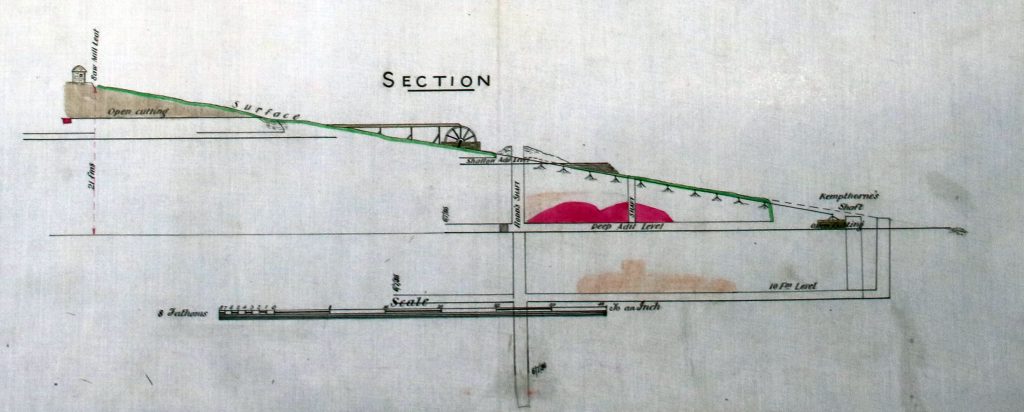

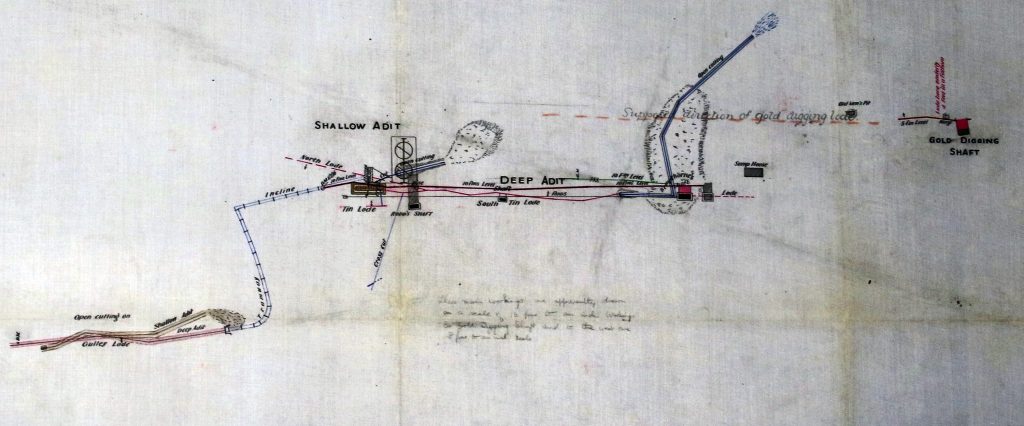

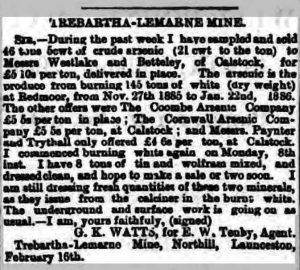

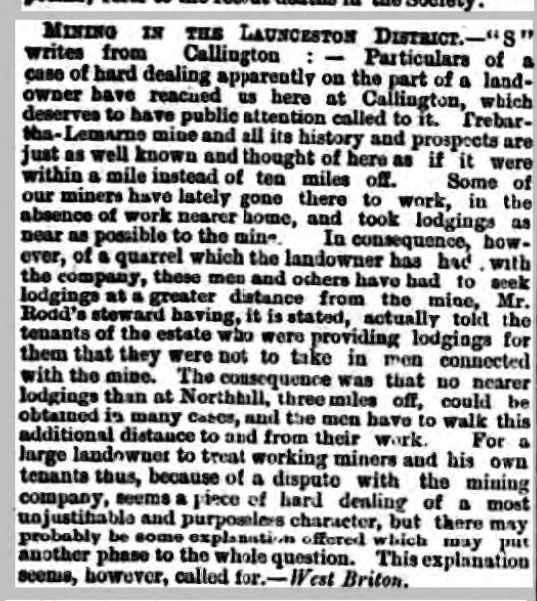

Edward Spoure’s apparent intention of working the mine was prevented by his death in 1696. His daughter, however, is said to have gone so far as to sink a shaft but owing to a fatal accident when a boy fell into it whilst playing with the windlass on a Sunday, the project was abandoned. At about this time the property passed by inheritance to the Rodd family into whose possession the ring found it’s way. The latter having sufficient income in dues from their mines around St. Day, long refused overtures to re-work the mine on their estate. At length in 1881 Mr Francis Rodd, the then owner of Trebartha, was persuaded to grant a lease. During the next seven years, the mine was worked by a local company who erected a 30-foot water-wheel for pumping and stamping and drove a cross-cut adit which intersected a new lode. On this Kempthorne’s Shaft was sunk to a depth of 10 fathoms and from here the adit was extended west to Rodd’s Shaft which reached a depth of 37 fathoms from the surface. Near this shaft, the lode which had averaged 2 to 4 ft. in width, opened out to nearly 6 ft. Further west, however, its size was reduced as it entered the granite. (Report by Josiah Thomas, Aug. 12th, 1885, plan dated 1888). During this working, operations were confined to the Middle Lode, no attention being paid to the Goldigging Lode on the north or the Gulley Lode to the south. Meanwhile, the noise from the stamps and fumes from the burning house were proving objectionable to the family and this fact, coupled with the lack of capital and hand-to-mouth methods of working, caused the mine to be abandoned in 1888. In the seven years, the mine produced a total of 20 tons of Black Tin as well as 18 tons of iron pyrites, 201 tons of crude and refined arsenic. 14 tons of tungstate of soda sold for £24 a ton. The mine was converted into a Limited Liability Company in September 1885. The mine was officially liquidated in September 1893.

In 1951, as a consequence of the exceptionally high price of wolfram, the mine was re-opened and continued in operation until January 1954. During this period some very good wolframite was found in the vicinity of the granite-killas contact in the western part of the sett. Eastward the lodes were principally productive of tin, although disturbed in this area by slides and crross0course. The mineralization, however, clearly extended far beyond the point reached in the most recent underground development as is apparent from the ancient outcrop workings along the backs. Shortly before its abandonment, the mine was inspected by Mr J. H. Tounson who reported that a tin lode in the deepest level eastward was showing excellent values. Due, however, to the heavy fall in the price of tungsten in which the company was primarily interested, and the high working costs consequent on having to transport the ore ten miles by road to the nearest milling plant at ‘New Consols’ near Luckett, this potentially important discovery was never explored. The mine, as a consequence, may still be regarded as having the making of a small but satisfactory tin producer and one which deserves a further and better trial than it has yet received. (Reports dated August 6th, December 26th 1953).

“Trebartha-Lemarne Tin Mine is situated on the Trebartha Estate very near to the mansion of F. R. Rodd Esq. and is worked at present by water power, and very recently a large outlay has been made in erecting works for separating tin, arsenic and other minerals. It has been worked by a local company for 7 years, Mr J. B. James of Plymouth is the Purser, and Capt H. Bennett of Redmoor [is] the Manager. The mine has a remarkable ancient history.” Venning’s Postal Directory of 1901.

Tremollet Mixed Mine

About three-quarters of a mile south of Coads Green, near the entrance to West Tremollett Farm, an adit has been driven northward from the stream, adjoining which is a grassed-over dump containing manganese oxides. The workings are not named on the map but were identified by Sir Arthur Russell as those of the Tremollett Manganese Mine, specimens from which were presented by Colonel Francis Rodd of Trebatha Hall to the Phillip Rashleigh collection about the year 1800. Working was later resumed as Coads Green Mine, with an output of 21 tons of manganese ore being recorded from the latter in 1876. (Sir Arthur Russell, Mineralogical Magazine Sept. 1946). A year later a manganese lode, 4 feet wide, was reported to have been cut on Ashwell Farm, “about 500 fathoms east of Old Tremollett Mine where upwards of £50,000 worth of manganese has been raised and sold.”(Advert Mining Journal, June 23rd, 1877). Prior to its enclosure in 1910 a number of mineral trials were carried out in the area of Tremollett Down. Among these was the ‘Prince Edward Copper Mine’ which in 1846 was held under a lease from H. R. H. Albert Edward, Prince of Wales. Captain Samuel Seccombe who inspected the property at this time stated that it had formerly been worked a ‘Tremollett Down Consuls’ when a shaft was sunk about 7 fathoms on a north-south lode, whilst several east-west lodes, showing traces of copper and lead ore, had also been laid open by costeaning (surface pitting) (Mining Journal July 4th, 1846). The Prince Edward “Mine” survived for little more than a year but in 1852 work was resumed by the ‘Tremollett Down’ company who drove an adit some distance south through hard, wet ground and sank a trial shaft on the north lode. In the following year mining circles in London were electrified by the news that this hitherto undistinguished copper and lead prospect was, in fact, one of the richest gold mines, the gossan (of which there was said to be an inexhaustible supply) having yielded no less than eight ounces of gold to the ton when tested by Berdan’s Machine. The company immediately placed an order for two of these patent separators, together with an engine capable of hoisting 1,000 tons of ore a month from which a profit of £300,000 a year was expected. (Mining Journal Sept. 18th, 1852 & December 24th, 1853). Expectations, as it proved, was all that the adventurers ever got for their money, since shortly after Berdan’s Machine was shown to be a fraud – or at best a hoax – which had been perpetrated on a gullible public. Although further tests by local assayers in 1855 proved some gold was present in the gossan, the mine was abandoned during that year with no recorded output.

Wheal Lanoy

Wheal Luskey was a copper mine opened in 1881 and which looked promising at first but was abandoned in 1886. It lies across the River Lynher due west of Trebartha Village just below West Castick.

St. Clether

projects well above the ground and is visible at a great distance from the north; it is known as Lanlavery Rock. The mine actually worked is situated on the west side of the marsh at Old Park, but shafts were also sunk on the east of the marsh and close to the farm, but no ore appears to have been raised. Further trials were made on the vein, on both sides of Lanlavery Rock, but little ore was met with. The great reef formed apparently by the same vein on the west of the granite, about the Devil’s Jump, does not appear to have been tried ; but so much of it stands out bare and clear of the ground that its barren nature is quite obvious. The veinstone met with here is of the porous type of quartz associated with pyrites.

South Petherwin

Tolpetherwin/Inny Consuls Mine.

On the eastern side of the Bodmin to Launceston road just above Two Bridges, lay the Tolpetherwin Mine. Trials were started here in 1844 by Messrs Gill & Rundle, the Tavistock bankers, and from a pit about 9ft. deep a ton of lead ore was raised containing 52 ounces of silver. A short time later three E.-W. copper lodes having been discovered, a shaft was sunk to 20 fathoms and an adit driven 60 fathoms, the work on this occasion being carried out under the supervision of ‘Mr Darke, steward to Squire Archer of Trelaske,’ the owner of the land. Operations were brought to a stop by an unexpected inrush of water with which the horse-whim, using bailing buckets, was unable to cope. The water is said to have been so much impregnated with copper as to coat the kibbles green overnight (Mining Journal April 10th, 1847).

In the early part of 1853 working was resumed at Tolpetherwin Mine by a small company under the title of Inny Consuls. By the end of October 1 35 x 10 ft. overshot wheel, constructed by Langdon & Pinch of Launceston, was installed and over three-quarters of a mile of leats had been cut to bring in water for driving it. The wheel was set in motion during the following month when working at 4 revolutions per minute, it drained the shaft to its full depth of 20 fathoms in 2½ hours. From the shaft bottom, a cross-cut was put out to one of the lodes which gave assays of 16¼% for copper and 120 ounces of silver per ton. From the 20 level, the shaft was subsequently continued down on the underlay to 36 fathoms. Here the lode was 18 inches wide and “it character more favourable than in either the 20 or deep adit levels.” Between the incline portion of the shaft “and the gate leading to the mill (Treguddick Mill) by the side of the turnpike road,” several small branches were believed to form a junction but although these showed high values for copper, lead and silver, together with traces of gold, the mine closed down in 1856 without recorded production. The materials were advertised for sale in April of the following year and included, in addition to the water-wheel, 70 fathoms of flat-rods, and 12 heads of stamps (Mining Journal November 4th, 1853, April 8th, 1854 & March 15th, 1856). Although abandoned so long ago, the shaft was still standing open in 1967, 310 yards N.N.E. of the northern bridge at Two Bridges. According to an unsupported statement by Dines, the adit emptied 140 yards S.S.W. of the shaft but no trace of any adit is visible in this position today.

April 7th, 1856

At Inney Consols meeting the accounts showed balance against adventurers of 22/.

Whilst copper and silver-lead were the minerals chiefly found in Inny Consols, the area to the south-west of Launceston is more generally characterised by deposits of manganese. The occurrence of this ore is widespread and in addition to those already described, trials have been recorded at Treguddick near Two Bridges in 1828, on Botatham Farm in 1842, and at South Petherwin during the 1870s (O.S. 16 S.W.). At this last site which lay about 200 yards N.W. of the village (on Botatham Farm), a shaft was sunk a few fathoms and a small quantity of ore returned. The pumps and debris of the workings were still in evidence in 1884 (Josiah Thomas Ecclesiastical commissioners, March 12th, 1884). The manganese ore was generally found in pockets but on the Barton of Trelaske, it occurred in a regular lode at about ten fathoms from the surface, to which depth it had been worked before 1824 (Samuel Drew, History of Cornwall, vol 2, p.417). In the course of that year the sale was advertised at the Dolphin Inn, Westgate Street, Launceston, of ten tons of manganese “now lying at Billing’s Wharf, Cotehel Quay” and about twenty tons of ore at Trewanta in Lewannick, “together with all the implements, floors and sheds standing there.” Included in the same sale was the sett of Pearse’s Trebursye.

Trewen/Laneast/Tresmeer/Tremaine

Trenault Lime and Copper Mining Company.

At Trenault Lime Quarry to the north of Polyphant and east of Trewen, limestone was worked for many years by means of long tunnels driven into the hillside. In one of these a copper lode was encountered and the strength of this the Trenault Lime and Copper Mining Company was formed in 1850. The lode, however, was found to be too much impregnated with mundic to be of economic value (Mining Journal 1850-1855 passim).

Beyond the 6th milestone from Launceston, the road to Camelford passes three miles over the moorland expanse of Laneast Downs. The area as Dr H. S. Boase observed in 1830, is an interesting one alike to the geologist and the miner, to the latter principally on account of its numerous deposits of manganese ore. “Many of these,” he wrote, “have been very productive but as far as I could learn the remuneration to the adventurers must be inconsiderable in consequence of the low price of this article and the heavy expense of land-carriage over a bad hilly road.”

This mine is situated on the north-east edge of Laneast Downs, 360 yards south-east of Lidcott farm in the parish of Laneast. It had been at work for many years prior to 1826 (Sir Henry English, a compendium of useful information relating to companies formed for working British Mines, 1826), when the lease, formerly granted by William Baron of Tregear (Tregeare), was renewed by his successor, John King Lethbridge, at 12/- per ton dues to the Lidcott Manganese Company. The earliest working consisted of a large cavern-like excavation with many ramifications, open to the day, and which is still accessible and well exhibits the nature of the deposit.

Later it was worked by shafts, of which there are several, communicating with an adit-level opening from the stream bottom to the north-east. The mine was last worked between the years 1875 and 1881 in conjunction with Westdownend farther to the north-east.

A 19th-century open cast manganese mine. In 1831 Dr Boase had this to say:-“The downs near ‘Letcot’ are very siliceous and even quartzose. They are interesting in an economical point of view, as containing extensive deposits of the ores of manganese. A mine of this substance has been long worked here. The ores occur in a lode or cross course of capel, running north-east and south-west; the lode in about twelve fathoms in width, and is composed of siliceous materials. or rather varieties of compact felspar, in which silex greatly predominates. The ore is arranged throughout the substances of the lode in veins and branches. In the latter form it was originally discovered,

not many feet below the surface, and in such abundance that it was obtained at a very trifling cost, for the hardiness and tenacity of the capel permitted the ore to be followed in all its ramifications without needing support: and the result of these operations has been to produce a large chasm, with curiously irregular and indented sides.” Inspecting the workings around the same time Boase stated that the workings, then 20 fathoms deep, were drained by a water-wheel pump, the ore occurring in a bed striking north-east and about 12 fathoms wide. In this, the manganese was found in veins and bunches and was followed down from within a few feet of surface in large cavern-like excavations, with many ramifications, some of which stood open to the day (H. S. Boase, Trans. Royal Geo. Soc. Cornwall, 1832, vol.4 pp. 232, 233). The deposit was later developed by shafts which connected to an adit brought up from the stream on the north-east.

West Down End Mine.

West Down End Mine was worked in 1818 under the grant to George and William Pearse, wool staplers of the Borough of Newport (Launceston), and John Prout of Linkinhorne, miner (Deed dated November 7th, 1818, C.R.O). From 1830 the mine was worked in conjunction with the Lidcott Mine. Both properties were active again in 1875-81, at which time the output from Lidcott amounted to 310 tons and from West Down End 115 tons (Gelog. Mem., Tavistock and Launceston, p.120).

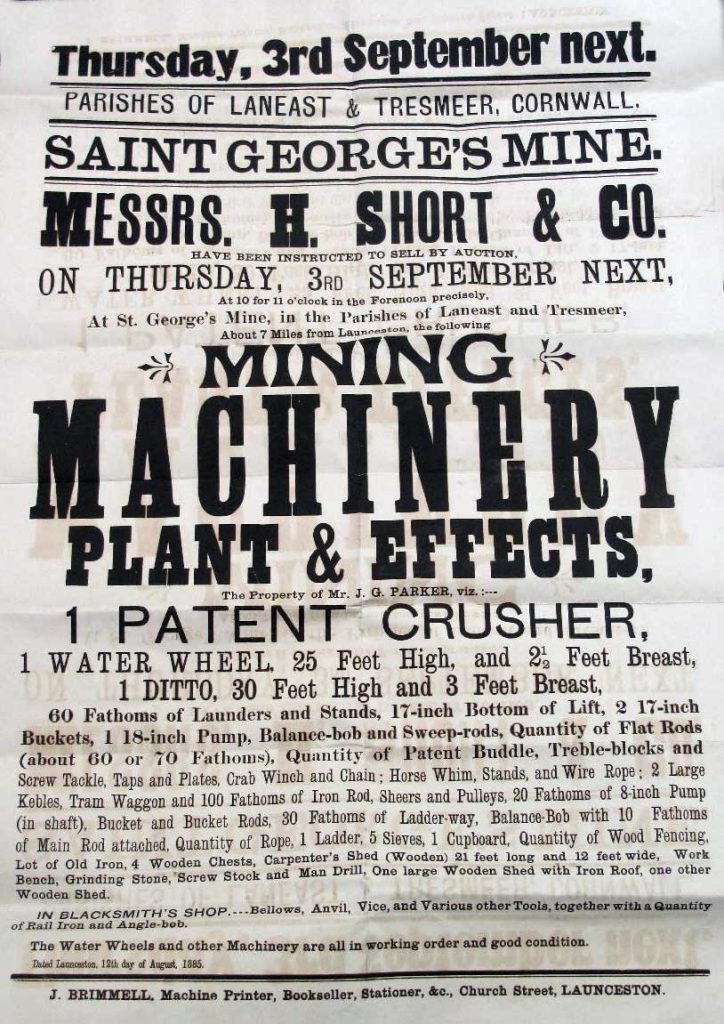

St. George’s Lead and Silver Mine/Wheal Baron

On Badgall Farm about one-mile north-west of Lidcott, work was in progress in 1853-55 at a mine called Wheal Baron, a name derived from the Baron family of Tregeare of which estate it formed part. In February 1854 the manager, Captain James Endean, reported that a trial shaft had been sunk and some 32 fathoms driven on a lode 2½ to 3 ft. wide and composed of quartz and mundic, spotted with rich sliver-lead ore. Assays of the latter gave produce of 46 ozs. of silver to the ton of ore and 25% for lead, together with the “equivalent to 17 dwts. 4 grs. of fine gold per ton.” The mine at this date had only been worked to a depth of about seven fathoms and operations appear to have ceased before the end of 1855 (West Briton March 3rd, 1854; Mining Journal March 4th, 1854; Kelly’s P.O. Directory of Cornwall, 1856). For reasons given later, it is clear that Wheal Baron corresponds with the mine shown on the O.S. map, 16 N.W., as St. George’s. Little is know of the latter under that name beyond the fact that it was being worked by Messrs Broderick & Parker in 1877-78, with a Captain Jos. Evans as manager (As recorded on Sir Arthur Russell’s annotated copy of the 6-inch map, 16 N.W.). Operations at this time seem to have been on a more extensive scale, no less than seven shaft burrows being now traceable (1966) on the property, extending in an N.-S. line. The mine closed in 1885.

In 1966 Mr A. B. Venning, senior of Launceston, then aged 85, described the appearance of the mine as he remembered it some years after its abandonment. What impressed him most as a child was the massive wooden headgear “topped by a tall mast which was a landmark for miles around.” There was no engine house or stack, the pumps being driven by a large water-wheel lower down the valley and connected to the shaft by a long line of iron flat-rods carried on overhead pulleys. The wheel was operated by water brought through a leat from Badgall Moors a mile away. The crushing and dressing plant adjoined the River Kensey, and a newly constructed road gave access to this from the workings. Hoisting was effected by a horse-whim. The name of the mine concluded Mr Venning, “was, we believe, Wheal Amy.” (The Cornish and Devon Post, January 22nd, 1966).

Beyond the River Kensey which formed the northern boundary of this last sett, considerable small-scale mining activity was formerly witnessed in the parishes of Tresmeer and Tremaine. On Trew Farm in Tresmeer, the Tithe Schedule of 1839 names a plot of ground near the river (number 10 on the Tithe Map) as “Manganese Floors.” On February 16th, 1859 a licence was granted by the Rev. William Rogers to Thomas Hicks of Truro, surveyor, to search for manganese throughout the tenements of Trew and Treglum, comprising the fields called Dinevors Floors, Lower Blackland, Higher West Town, Trew and Treglum Down, and North Park (Numbered respectively 10, 14, 17, 28, 33 and 35 on the Tresmeer Tithe Map; Percival Rogers Collection C.R.O. wherein is contained the subsequent correspondence between the Rev. W. Rogers and Thomas Barnard). The licence seems to have lapsed after twelve months but in the 1860s more extensive trials were carried out in this area by an impecunious character named Thomas J. Barnard, under similar grants from the Rev. William Rogers, Rector of Mawnan, the owner of the land. The work was largely sustained by the latter, Barnard himself being, in his own words, “a sorry capitalist” although endowed with considerable skill in extracting sums of money from the often reluctant, although never wholly disillusioned, clergyman. Among the principal sites inspected was Treglum Down, now forming part of Trew Farm, which being almost due north of Wheal Baron (otherwise St. George’s) was thought to be traversed by the lodes of that mine.

On November 6th, 1864 Barnard informed Mr Rogers that a level driven 32 fathoms on another N.-S. lode near the Churchtown of Tremaine was expected to yield silver-lead, and also black-lead ore suitable for polishing stoves. He himself had spent £50 on the various operations, “a small amount for mining,” but was unable to do more on his own account. Rogers replied that he was inclined to adventure a little money but thought it best to go on with the Tremaine Mine and leave Treglum for a while. On January 11th, 1865, Barnard writing in his usual sanguine style states that gold was likely to be found in the area “as I have heard on good authority that when the old mine on Mr Lethbridge’s property was worked some of the floocan assayed by a London assayer (gave produce) equal to 1 oz of gold to the ton of stuff. However, silver-lead is the thing in view. I am not thinking of gold save in the shape of the coin of the realm.” The letter concludes with the suggestion that Rogers should put £400 into the Tresmeer Mine and thereby acquire a 2/3 interest in the concern. This offer Rogers tactfully declined but forwarded a cheque for “25 to enable Barnard to carry on. In the June of 1865, Barnard received a call from Captain Endean who advised him to further open up the Treglum Mill lode or ‘Wheal Emma’ as it had then become known. “He was the Captain of the mine worked on Mr Lethbridge’s property some 14 years since and has assured me of having brought out his cap full of clean prills of silver-lead from the short level driven in that mine. The assays gave 8 to 16 ounces of silver to the ton. I have Mr Lethbridge’s consent to drive through his meadow and so could commence from the river upon the lode.” About this time, although it bears no date, a printed prospectus was issued of the ‘Wheal Emma Silver-Lead & Copper Mining Company, Tresmeer, near Launceston,’ with a proposed capital of £3,000 in £1 shares. “The sett embraces Horn Parks, Treglum and parts of the Trew estates. To the south are the old workings of a mine known several years since as ‘Wheal Baron’ where small quantities of rich silver-lead ore were taken from about 4 fathoms from the surface. This was abandoned when the few adventurers were lacking the needful to put up the requisite machinery for its development. There are tow known lodes in the Wheal Emma sett, one of them caunter on which several trial shafts have been sunk to a depth of 2½ fathoms, and a short level 3 fathoms driven upon the hanging wall. Assays show from 8 to 84 oz. of pure silver from 1 ton of raw floocan. It is proposed to erect a smelting works. The present proprietor or grantee of the sett is Mr Thomas Barnard of Langore, by Launceston.” It is probable that this document was merely a draft and never publicly circulated.

Meanwhile, further references appear in the correspondence to the level of Tremaine, and also to a mine called ‘Trewetle.’ The latter was likewise situated in the Tremaine parish and by 1864 an adit had been taken up here from the river bottoms and driven 35 fathoms north into the hill on a lode varying from 1 to 1½ ft. in width and containing quartz and caple, with occasional spots of copper ore (Report by William Johns of West Caradon Mine, February 6th, 1865). The name Trewetle is not shown on either the Tithe or Ordnance Survey maps and is entirely unknown in the district today. It arrives probably from either a mis-spelling or local pronunciation of ‘Treburtle,’ a well known hamlet and farm in the Tremaine parish where, according to Mr R. F. A. Heard who farmed there for many years, “there is an old mine at the bottom of Penrose Lane, at the lower end of the farm near the Devon border (the Cornwall-Devon border then followed the River Ottery). It is in the last field down on the right-hand side, close by the Cornish bank of the river.” (O.S. 12 S.W.)

The correspondence between Barnard and Rogers, amounting to scores of letters, continued for several years; until eventually the former took himself off to London and thence to a job at a Welsh quarry, near Caernarvon. Meanwhile, Mr Rogers had not abandoned all hopes of his mineral property. In 1879 he sought the advice of Mr J. H. Collins on manganese working in Treglum Down named ‘Wheal Job.’ Collins reported that a shaft had been sunk to the bed at about 6 fathoms depth and a level extended N.W. and S.E. from the bottom for about 6 fathoms. About 15 tons of lode material had been obtained, estimated to yield some four or five tons of ore when dressed. Collins’s analysis of some of the dressed ore showed 29.5 per cent of peroxide of manganese but he thought that by hand-picking the proportion might be raised to 50%. Although low in value, the quantity made it an attractive proposition. He accordingly advised the sinking of an inclined shaft to 20 or 30 fathoms in order to prove the deposit at greater depth.

In 1881, ‘Wheal Job’ was granted to a Captain Sampson Dyer who apparently carried out some further work. A report by John Curtis of Marazion in 1886 states that the Western Shaft had been sunk vertically to 50 ft. The 24 level extended 15 ft. east, passing through a lode 3 ft. wide with a leader 1 ft. in width which yielded, in places, two tons of manganese per fathom. “If it is worth what Captain Dyer thinks it to be viz. £3 or £4 per ton, it is a good paying property.” About 50 ft. east was another shaft from which good work had been raised from a branch 2 inches wide. A third shaft, a little to the north had a pile of lode stuff near it but not as good as that from the Western Shaft, “In the hill below the Farm House is an iron lode 6 feet wide – this should be opened up to see what is there.” The writer concludes with the remark that “from the run of the lodes in St. George Mine (lead) it is clear they are in your property but as no trial has been made on them, there is nothing to report on” (Percival Rogers Coll, C.R.O.). This statement suggests that ‘Wheal Job’ adjoined the erstwhile ‘Wheal Emma’ sett.

Owing to the absence of any mining map of the area it is now impossible to identify the exact sites of workings such as these, the shallow pits of which they consisted having long since been filled. In contrast to this, the Tremaine adit on Bray Farm was still well known in 1969 and was being explored by the present occupier, Mr John Statton, a few years since. The adit proved to have been driven for a very considerable length, “right up under Tremaine,” and inside it were found an old hat and a pair of boots left there by the former workers. There were two ‘shafts’ (winzes?) in the adit, both filled, and a great volume of water coming through it. A dam was put in with the idea of utilising this to supply the farm but the water was too much contaminated to serve such a purpose. Mr Statton’s father further records that the mine was worked “about 100 years ago as there was supposed to be wolfram (more probably manganese) there, but they didn’t get anything, and the men working there passed around the hat to raise enough money to send the man who started it all back to London” – an interesting folk memory of Thomas Barnard’s departure from the local scene (Arthur Venning and the Cornish and Devon Post).

Other possible mining sites have been reported at the foot of Trehummer Hill, at Combe Lake and at Treburrow but the existence of these is somewhat doubtful. Surprisingly, nothing appears to be known of the two most obvious traces of mining noted by the writer in this district. One of these consists of a shaft burrow (still singularly fresh in appearance) which lies on the river bank adjoining the south end of the bridge by Treglum Mill; the other being an adit from which water still flows, near the stream-head a quarter of a mile west of Splatt. Some three-quarters of a mile further north-west, a mine which returned some lead ore was once in existence at Reddyford Mill. The fact that it had a steam engine (Nicholas Ennor, Mining Journal, Supplement, March 7th, 1874) suggests that it was worked on a more extensive scale than most of the small concerns in this neighbourhood but no memory of it now survives nor can any trace of its whereabouts on the ground be found.

Visits: 773