Abstract

Lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP) occurs in response to a large variety of cell death stimuli causing release of cathepsins from the lysosomal lumen into the cytosol where they participate in apoptosis signaling. In some settings, apoptosis induction is dependent on an early release of cathepsins, while under other circumstances LMP occurs late in the cell death process and contributes to amplification of the death signal. The mechanism underlying LMP is still incompletely understood; however, a growing body of evidence suggests that LMP may be governed by several distinct mechanisms that are likely engaged in a death stimulus- and cell-type-dependent fashion. In this review, factors contributing to permeabilization of the lysosomal membrane including reactive oxygen species, lysosomal membrane lipid composition, proteases, p53, and Bcl-2 family proteins, are described. Potential mechanisms to safeguard lysosomal integrity and confer resistance to lysosome-dependent cell death are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the last decade, the lysosome has emerged as a significant component of the cellular death machinery. Lysosomes, which were first described by de Duve and colleagues in 1955 [1], are acidic, single-membrane bound organelles that are present in all eukaryotic cells [2]. The primary function of lysosomes is degradation of macromolecules, and for this purpose, lysosomes are filled with more than 50 acid hydrolases, including phosphatases, nucleases, glycosidases, proteases, peptidases, sulphatases, and lipases [2]. Of the lysosomal hydrolases, the cathepsin family of proteases is the best characterized. The cathepsins are subdivided, according to their active site amino acids, into cysteine (cathepsins B, C, F, H, K, L, O, S, V, W, and X), serine (cathepsins A and G), and aspartic cathepsins (cathepsins D and E) [3].

Cell death through apoptosis is tightly controlled by changes in protein expression, protein-protein interactions, and various post-translational modifications, including proteolytic cleavage and phosphorylation. For some of these events to occur, proteins must re-localize from one sub-cellular compartment to another to gain access to their substrates or interacting partners. Thus, compartmentalization is yet another important regulatory mechanism, preventing accidental triggering of cell death signaling. The most obvious example is the release of apoptogenic factors from mitochondria, a key event in the execution of cell death, which is regulated mainly by proteins of the Bcl-2 family. Lysosomal hydrolytic enzymes were initially thought to inevitably trigger necrotic cell death when released into the cytosol [4]. However, in 1998, we discovered that the aspartic protease cathepsin D was redistributed from lysosomes to the cytosol upon oxidative stress-induced apoptotic cell death [5] (Fig. 1). Cathepsin D was the first identified lysosomal protein with apoptogenic properties, but the subcellular location of the protein in dying cells was not addressed in the early publications [6, 7]. In a series of papers from Brunk and co-workers, it was established that the extent of lysosomal damage determines the cell fate; a limited lysosomal release results in cell death by apoptosis, while massive lysosomal break-down leads to necrosis [8–12].

Apoptosis-associated release of lysosomal cathepsin D into the cytosol. Visualization of cathepsin D in rat cardiomyocytes exposed to the redox-cycling drug naphthazarin by immunofluorescence microscopy (a and b) or immuno-electron microscopy using antibodies tagged with ultra-small gold particles and subsequent silver enhancement (c and d). There is a shift from a punctate lysosomal staining pattern in control cells (a) to a diffuse cytosolic staining in cells exposed to naphthazarin (b). Likewise, in electron micrographs (c), cathepsin D can be seen in lysosome-like structures in control cells (arrows), while in cells treated with naphthazarin (d), cathepsin D is spread throughout the cytosol (arrow heads), bars = 30 μm (a and b) and 1 μm (c and d)

It is now generally accepted that apoptosis is often associated with release of cathepsins into the cytosol, and that, in addition to cathepsin D, cysteine cathepsins B and L are involved in apoptosis signaling [13–17]. Moreover, lysosomal destabilization, which will subsequently be referred to as lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP), may also occur during other types of cell death, including necroptosis and autophagic cell death [18, 19]. LMP can be triggered by a wide range of apoptotic stimuli, including death receptor activation, endoplasmic reticulum stress, proteasome inhibition, oxidative stress, DNA damage, osmotic stress, and growth factor starvation [13–17]. In some experimental settings, lysosomal release is an early event essential for apoptosis signaling to proceed, while under other circumstances LMP occurs late in the cell death process and contributes to amplification of the death signal (Fig. 2). Cathepsin relocalization seems to be critical for apoptogenicity, and it has been demonstrated that microinjection of cathepsins into the cytosol is sufficient to trigger apoptotic cell death [20–22]. Cathepsin release may result in caspase-dependent or -independent cell death with or without involvement of mitochondria [13, 17]. Caspases-2 and -8, phospholipase A2 (PLA2), sphingosine kinase-1, and the Bcl-2 family proteins Bid, Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, and Mcl-1 may all be downstream _targets of cathepsins. A detailed description of the mechanisms by which lysosomal cathepsins propagate the apoptotic signal can be found elsewhere [13–16].

Lysosomal participation in cell death signaling. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP), i.e., release of cathepsins from lysosomes into the cytosol, is an important step in cell death signaling induced by a variety of stimuli, such as death receptor activation, radiation, and cytotoxic drugs. Several cytosolic cathepsin _targets have been described and the signaling downstream LMP involves both caspase-dependent and -independent pathways. Engagement of the mitochondrial pathway is a common downstream event of LMP, but cathepsins may also cause cell death without involvement of mitochondria

It is still unclear whether a subset of lysosomes is particularly susceptible to apoptosis-associated LMP and thus release all of their contents while other lysosomes release none, or if all lysosomes within a given cell are equally affected but release only part of their contents. There are, however, indications that interlysosomal differences regarding vulnerability to LMP do exist [23, 24]. For example, large lysosomes appears to be more susceptible to LMP than small ones [24].

The mechanism underlying LMP is still incompletely understood. Apart from cathepsins, other hydrolases [25–28], H+ (causing acidification of the cytosol) [29], Ca2+ [30], and several of the dyes that accumulate in lysosomes with intact membranes, e.g., acridine orange [8], Lucifer Yellow [10], and LysoTracker [31], can escape into the cytosol at the onset of apoptosis. This may suggests a nonspecific release mechanism, such as pore formation or limited membrane damage, rather than selective transport across the membrane, which would likely be specific for a single group of molecules. However, it should be noted that the release of H+, Ca2+, and lysosomotropic dyes does not necessarily reflect a change in membrane integrity, but could merely be due to a change in ion pump activity. It has been suggested that apoptosis-associated lysosomal release is size-selective, as 10- and 40-kDa FITC-dextran molecules are released from lysosomes during staurosporine-induced T-cell apoptosis, while 70- and 250-kDa FITC-dextran molecules are retained [32]. Nevertheless, that upper limit of size-selection does not apply in all death models, as release of the 150 kDa lysosomal protein N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase has been observed under other experimental conditions [25–27]. Conceivably, LMP may be governed by several distinct mechanisms, each with its own characteristics, which are likely engaged in a death stimulus- and cell-type-dependent fashion. The mechanisms that have been suggested to contribute to permeabilization of the lysosomal membrane are described in the following sections, as are those that are thought to safeguard lysosomal integrity and confer resistance to lysosome-dependent cell death.

Promoters of lysosomal membrane permeabilization

Viral and bacterial proteins

Apoptosis triggered by bacterial and viral infections sometimes involves LMP, and in certain contexts the participation of cathepsins is required for apoptotic signaling to proceed [33–38]. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) protein Nef is one of the non-mammalian proteins that, when entering mammalian cells, causes permeabilization of the lysosomal membrane [36]. Overexpression of Nef elicits an apoptotic response in CD4+ T lymphocytes via disruption of lysosomal integrity, thus, the progressive and massive destruction of CD4+ T lymphocytes characteristic of HIV-1-related disease may in part be due to Nef-induced LMP. Parvovirus H1 is another virus that induces cell death characterized by translocation of cathepsins to the cytosol [34]. A small amount of viral proteins were found within the lysosomal fraction, and it was speculated that the capsid protein VP1, which possesses a domain displaying phospholipase A2 (PLA2) activity, could be involved in induction of LMP.

The diphtheria toxin is one of the most interesting examples of a bacterial protein that can permeabilize the membranes of the endolysosomal compartment. After entering the cell via endocytosis, one of the subdomains of the toxin inserts into the endosomal membrane and forms pores through which the catalytic subunit of the toxin passes into the cytosol [39–42]. In the same way, components of the tetanus [43], botulinum [44], and anthrax [45] toxins are believed to permeabilize the endosomal membrane to gain access to the cytosol. As discussed below, certain mammalian proteins involved in apoptosis signaling share high sequence homology with these viral proteins, and may well be key regulators of apoptosis-associated LMP.

Pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins

The Bcl-2 family consists of both pro- (e.g., Bax, Bak, Bid, Bad, Bim, Noxa, and Puma) and anti-apoptotic (e.g., Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, and Mcl-1) proteins that are critical regulators of the mitochondrial pathway to cell death. The multi-domain proteins Bax and Bak are pore-forming proteins that enable the release of apoptogenic factors such as cytochrome c from mitochondria, while the so-called BH3-only-domain proteins (e.g., Bid, Bad, Bim, Noxa, and Puma) serve to promote activation of these multi-domain family members upon an apoptotic insult. The main function of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins, on the other hand, is to prevent the release of apoptogenic factors. Interestingly, the hypothesis that Bcl-2 family proteins can release cytochrome c through pore formation was based on the discovery that some of these proteins showed high structural similarity to the pore-forming domain of the diphtheria toxin, which, as mentioned above, is known to form pores in the endosomal membrane [46, 47]. Several years later, we discovered that Bax could also permeabilize the lysosomal membrane, and thereby promote cell death by the release of lysosomal cathepsins to the cytosol [26]. Confocal and immuno-electron microscopy showed that Bax translocated from the cytosol to the lysosomal membrane upon staurosporine treatment of human fibroblasts. Furthermore, recombinant Bax was inserted into the membrane of isolated rat liver lysosomes and caused the release of lysosomal constituents. These data provided the first evidence that Bax is mechanistically involved in LMP and are now supported by a growing number of publications demonstrating involvement of multiple pro- and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins in the regulation of lysosomal membrane integrity.

Bax is activated and relocated to lysosomes in hepatocytes upon treatment with free fatty acids [48, 49], in cholangiocarcinoma cells in response to tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis inducing ligand (TRAIL) [50], and in ovarian cancer cells treated with etoposide [51]. In all three cases, small interfering RNA- (siRNA)-mediated downregulation of Bax prevented LMP, indicating a mechanistic importance of Bax’s lysosomal location. Furthermore, siRNA-mediated downregulation of Bim was found to prevent TRAIL-induced LMP [50]. Bim was activated upon TRAIL treatment and colocalized with Bax in lysosomes, suggesting that it may trigger Bax-mediated LMP. In another study, Bid, the most well-known Bax activator, was found to be involved in tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α-induced lysosomal destabilization in hepatocytes [52]. Upon TNF-α treatment, Bid was detected in lysosomes, and cathepsin B was released to the cytosol. However, no such release was seen in Bid−/− cells. Even though the involvement of Bax was not considered in this study, it is tempting to speculate that LMP was caused by Bid-mediated activation of Bax. In a recent report, BH3 domain peptides were found to permeabilize isolated lysosomes in the presence of Bax [50]. Interestingly, Bak, the other main pore-forming Bcl-2 family protein, also localizes to lysosomes [48], but there are as yet no reports of Bak-induced LMP. Conceivably, triggering of LMP could be a general function of pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins. Similar to mitochondrial membrane permeabilization [53], LMP-associated Bax activation seems to rely on different BH3-only proteins depending on the death stimulus and cell type. In addition to a direct effect of Bcl-2 proteins at the lysosomal membrane, Bcl-2 family members may regulate LMP at the mitochondrial level as engagement of mitochondria can lead to increased lysosomal release via positive feed-back. However, as release of cathepsins has been observed in Bax/Bak double knockout cells there are clearly additional mechanisms independent of Bax and Bak that contribute to LMP [54].

p53

Permeabilization of the lysosomal membrane occurs in p53-induced apoptosis [55], during which p53 itself localizes to lysosomes and triggers LMP in a transcription-independent manner [56]. It was proposed that p53 phosphorylated at Ser15 (p-p53Ser15) may be recruited to the lysosomal membrane by a newly discovered protein called Lysosome-associated apoptosis-inducing protein containing the pleckstrin homology and FYVE domains (LAPF). This protein, which associates with lysosomes upon induction of apoptosis, is essential for cell death induced by TNF-α, ionizing irradiation, and the DNA-damaging drugs 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin [56, 57]. Downregulation of either p53 or LAPF prevented TNF-α-induced LMP [56]. Interestingly, silencing of LAPF expression abrogated lysosomal translocation of p-p53Ser15, whereas silencing of p53 expression had no effect on lysosomal translocation of LAPF, indicating that LAPF may trigger LMP by acting as an adaptor protein for p-p53Ser15. Furthermore, p-p53Ser15 localizes to lysosomes in cultured cortical neurons after exposure to the psychoactive ingredient of marijuana, ∆9-tetrahydrocannabiol [58], or β-amyloid [59], both of which cause neuronal cell death. Also in these models of apoptosis, LMP was abrogated by siRNA-mediated downregulation or chemical inhibition of p53. It is worth noting that p53, under certain circumstances, localizes to the mitochondrial membrane during apoptosis and can trigger mitochondrial membrane permeabilization by direct interaction with Bcl-2 family members [60, 61]. It is tempting to speculate that a similar mechanism governs p53-induced LMP. Additionally, p53 promotes Bax-mediated mitochondrial membrane permeabilization through transcriptional upregulation of the BH3-only-domain proteins Puma and Noxa [62–64]. In this way, p53 may engage the lysosomal pathway without translocating to lysosomes. Recent data from our lab supports this notion; ultraviolet B- (UVB)-induced, p53-dependent LMP is associated with an increase in Puma and Noxa expression without the appearance of p53 at the lysosomal membrane [65].

Proteases

Caspases

There are a number of publications suggesting that caspases, under certain circumstances, are involved in the release of apoptogenic factors from lysosomes [50, 52, 66–69]. Caspase-8, in particular, plays a significant role in the engagement of the lysosomal death pathway following death receptor activation [50, 52, 67–69]. Caspase-8 can trigger the release of cathepsins from purified lysosomes, and the effect was enhanced by the addition of a cytosolic fraction [67], indicating that caspase-8-induced LMP is at least partly mediated by activation of one or several cytosolic substrates. Bid, which presumably would trigger Bax-mediated LMP, has been presented as a possible candidate [52]. In our hands, neither caspase-8 nor activated Bid alone permeabilized the membrane of isolated lysosomes [26], suggesting that additional factors, such as Bax or Bak, are indeed required. In another intriguing study, caspase-8 cleaved and activated caspase-9 in an apoptosome-independent fashion [68]. By using genetically modified mouse embryonic fibroblasts, caspase-9 was proven to be indispensable for triggering LMP, but the exact mode of action remains elusive. Interestingly, depletion of Bid did not prevent the loss of lysosomal membrane integrity. These data suggest that there are at least two different mechanisms by which caspase-8 is able to induce LMP.

In a recent study, caspase-2 activation was shown to be required for LMP during endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis [70]. The effect was not dependent on Bax, ceramide, Ca2+, or reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, suggesting a more direct role of caspase-2. Indeed, caspase-2 has previously been shown to induce cathepsin release from purified lysosomes [67].

Cathepsins

It has been proposed that lysosomal proteases, in particular cathepsin B, may contribute to their own release [31, 48, 71]. In mouse hepatocytes, lysosomal destabilization evoked by TNF-α and sphingosine is dependent on cathepsin B, as induction of LMP fails in cathepsin B-deficient cells [31]. Moreover, chemical inhibition of cathepsin B significantly reduces both free fatty acid- and TRAIL-induced LMP [48, 71]. However, it is not clear whether intra- or extralysosomal cathepsin B is involved. As cathepsin B is constitutively active inside lysosomes, it cannot be sufficient for LMP; however, it may be necessary. Data in favor of intralysosomal cathepsin B as a mediator of LMP was provided by cell-free experiments in which sphingosine was found to cause lysosomal release from cathepsin B-containing but not from cathepsin B-deficient lysosomes [31]. Alternatively, cathepsin B-mediated LMP may constitute an amplifying feedback loop, in which a small amount of released cathepsin B triggers more extensive LMP from outside the lysosome. The latter is supported by the finding that upregulation of serine protease inhibitor 2A, a potent inhibitor of cathepsin B located in the cytosol and nucleus, reduces lysosomal breakdown [72].

Calpains

Calpains catalyze lysosomal membrane destabilization during neuronal cell death [73–76]. Cell death induced by ischaemia or hypochloric acid is associated with an increase in cytosolic [Ca2+], activation of calpains, and LMP. Activated μ-calpain localizes to the lysosomal membrane prior to release of cathepsins, indicating involvement in the triggering of LMP [74, 75, 77]. In further support of this hypothesis, μ-calpain can permeabilize the membrane of isolated lysosomes [67], and pharmacological inhibition of calpains abrogates LMP [73]. Interestingly, calpain activity correlates with the appearance of p-p53Ser15 at the lysosomal membrane, suggesting that calpains may, under certain circumstances, promote p53-mediated lysosomal release [59].

Reactive oxygen species

An increased production of ROS may lead to destabilization of the lysosomal membrane via massive peroxidation of membrane lipids. Photosensitizers located in lysosomes that generate singlet oxygen upon radiation have been shown to cause rapid release of cathepsins to the cytosol [78–80]. Moreover, apoptosis induced by UVA radiation or H2O2, both of which trigger cell death mainly by generating oxidative stress, involves LMP [12, 65, 81]. Additionally, other apoptosis inducers, e.g., N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)retinamide [82] and vacuolar ATPase inhibitors [83], cause ROS-dependent LMP. However, in the latter model systems it is not clear whether leakage over the lysosomal membrane is due to ROS-mediated membrane damage. Alternatively, alterations in the intracellular redox balance may elicit a redox-dependent signaling cascade resulting in LMP.

Induction of LMP by lysosomal membrane peroxidation reactions has been extensively studied in model systems in which the intralysosomal iron content has been manipulated [84–88]. It is hypothesized that intralysosomal iron, originating from degraded metallo proteins, reacts with H2O2 and generates highly reactive hydroxyl radicals that initiate peroxidation of the lysosomal membrane (Fig. 3). In an illustrative experiment, macrophages that were allowed to phagocytose silica particles with high amounts of surface-bound iron suffered from extensive lysosomal damage, while those that ingested silica particles pretreated with the pharmacologic iron chelator desferrioxamine displayed only modest lysosomal leakage [89]. In several additional studies it has been established that phagocytosis of iron complexes or iron-containing proteins increases lysosomal vulnerability, while a reduction in intralysosomal reactive iron reduces lysosomal leakage and cell death [84–88].

Destabilization of the lysosomal membrane by lipid peroxidation. In response to oxidative stress, increased amounts of hydrogen peroxide can diffuse into the lysosome. In the lysosomal lumen, the acidic milieu and the presence of low-molecular-weight iron, derived from degraded iron-containing proteins, promotes the reduction of iron and the generation of hydroxyl radicals. The hydroxyl radicals induce peroxidation of membrane lipids and thereby cause leakage of lysosomal constituents into the cytosol

Kinases

Cellular signal transduction involves a wide range of small GTPases and kinases constituting a complex signaling network that ultimately regulates virtually all cellular events including cell proliferation, differentiation, and cell death. Ras signaling pathways participate in the overall regulation of lysosomal function, and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K), one of the downstream _targets of Ras, is indispensable for vesicular transport to lysosomes [90–92]. H-ras driven transformation of NIH3T3 cells causes increased expression of cysteine cathepsins and reduced lysosomal stability during TNF-induced cell death [93]. Inhibition of PI3K sensitizes vascular endothelial cells to cytokine-induced apoptosis by increasing lysosomal permeability [94]. Furthermore, activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) promotes lysosomal breakdown in response to TNF-α, TRAIL, and UVB radiation, possibly via activation of the BH3-only-domain protein Bim [50, 95, 96]. Additionally, in neurons exposed to β-amyloid, phosphorylation of p53 at Ser15 is JNK1 dependent [97]. In contrast, inhibitors of JNK fail to affect lysosomal permeability in H-ras transformed NIH3T3 cells. Instead, activation of the Raf1-extracellular signal-regulated kinase (-ERK) pathway is responsible for increased engagement of the lysosomal death pathway [98]. Taken together, these data suggest that LMP is likely regulated by kinase-dependent signaling events, although the number of studies so far is limited.

Changes in lysosomal membrane lipid composition

Obviously, the lysosomal membrane composition plays a key role in the maintenance of lysosomal integrity. Damage to lysosomal membrane components or changes in the membrane structure and fluidity could result in lysosomal destabilization.

PLA2, phospholipase C, and sphingomyelinase, enzymes that regulate the membrane lipid composition, all show increased activity in the presence of high cytosolic [Ca2+], which is characteristic of apoptosis. Studies using isolated rat lysosomes have shown that these enzymes [99–102] as well as the phospholipid products arachidonic acid [103], lysophosphatidylcholine [104], and phosphatidic acid [105], affect the osmotic sensitivity of lysosomes, making them more susceptible to osmotic stress.

PLA2 stands out as a particularly interesting candidate because it is involved in lysosomal membrane destabilization in several different experimental systems [30, 76, 106–109]. For example, lysosomes are permeabilized in a PLA2-dependent fashion in response to low concentrations of H2O2 [106]. In this context, activation of PLA2 is dependent on an early minor release of lysosomal contents (suggesting an alternative mechanism for the initial release), and PLA2 engages in an amplifying feed-back loop. Notably, incubation of PLA2 with rat liver lysosomes results in leakage of lysosomal constituents.

Apoptosis-associated LMP may also be mediated by an increase in the sphingolipid sphingosine [10, 31]. Ceramide is produced from sphingomyelin upon activation of sphingomyelinases (SMase) and is further processed into sphingosine by ceramidase [110] (Fig. 4). It has been proposed that sphingosine accumulates inside lysosomes, where it permeabilizes the membrane in a detergent-like fashion, resulting in cell death [10]. Under certain circumstances, sphingosine-induced LMP is dependent on cathepsin B, as sphingosine fails to permeabilize lysosomes from cathepsin B−/− hepatocytes [31]. These data also present the possibility that sphingosine serves as a general trigger of cathepsin B-mediated intralysosomal events leading to LMP.

Accumulation of sphingosine leads to lysosomal membrane permeabilization. An apoptotic stimulus, e.g., tumor necrosis factor-α, leads to increased activity of sphingomyelinase, which catalyzes the formation of ceramide from sphingomyelin. By the action of ceramidase, ceramide is then converted into sphingosine, which accumulates in lysosomes and acquires detergent-like properties, leading to lysosomal membrane permeabilization

In a recent publication, proteins upregulated in lysosomes at the onset of apoptosis-associated LMP were identified using a proteomic approach [111]. Interestingly, two of these proteins, prosaposin and protein kinase Cδ, can lead to activation of the lysosomal enzyme acid SMase. Protein kinase Cδ activates acid SMase after translocating from the cytosol to the lysosomal membrane [112], and prosaposin is the precursor of four lysosomal sphingolipid activator proteins (saposins A-D) that promote acid SMase-mediated sphingomyelin degradation [113].

Other factors

β-Amyloid

Alzheimer’s disease is an age-related progressive neurodegenerative disease in which β-amyloid peptides are thought to confer neurotoxicity. Accumulation of β-amyloid in lysosomes of cultured cells results in LMP-dependent cell death [114, 115]. As β-amyloid is amphipathic and forms micelle-like aggregates [116, 117], the toxicity of β-amyloid could be mechanistically similar to that of lysosomotropic detergents, which self-assemble into micelles within lysosomes [118]. Alternatively, β-amyloid, which, like some of the Bcl-2 family proteins, shows structural similarities to pore-forming bacterial toxins, may trigger lysosomal release by creating pores. Indeed, oligomeric β-amyloid can incorporate into artificial lipid bilayers and form pore-like structures [119, 120].

Apolipoprotein E

Apolipoprotein E (apoE) is involved in lipid transport and one of its three major isoforms, apoE4, is a known risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. ApoE4-transfected cells are more susceptible to lysosomal leakage induced by β-amyloid as compared to untransfected cells or cells transfected with apoE3 [121]. This effect is dependent on a low intralysosomal pH, as overexpression of apoE4 fails to potentiate leakage from lysosomes neutralized with bafilomycin or NH4Cl. Furthermore, at acidic pH, apoE4 binds more avidly to phospholipid bilayer vesicles and potentiates β-amyloid-induced disruption to a greater extent. It was suggested that, especially at a low pH, apoE4 is converted into a molten globule capable of binding and altering membrane stability [122]. Thus, such apoE4-mediated effects on membrane stability are likely restricted to the lysosomal membrane, and may, under certain circumstances, play a significant role in the determination of cell fate.

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor

In a murine hepatoma cell line in which TNF-α-induced cell death was found to be independent of caspase-8, LMP was dependent on the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (Ahr) [123]. This receptor is a ligand-activated transcription factor whose _target genes are involved in many cellular functions, including apoptosis. In addition, it has been suggested that the Ahr may have ligand-independent activities. Ahr deficiency prevents disruption of lysosomes induced not only by TNF-α treatment, but also following photodynamic therapy [124].

ANT

The adenine nucleotide translocator (ANT) agonist atractyloside, which triggers opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore and release of mitochondrial cytochrome c, was shown to also induce release of cathepsin B from isolated lysosomes [125]. This was accidentally discovered by researchers aiming to identify factors released from a mitochondrial fraction, apparently contaminated with lysosomes. This finding suggests that ANT-like proteins may be present in the lysosomal membrane and regulate its permeability; however, in our hands, only a very high concentration of atractyloside permeabilized the membrane of isolated rat liver lysosomes [26].

Granulysin

The killer effector molecule granulysin, which, together with perforin and granzymes, is located in the cytolytic granules of human cytotoxic T-lymphocytes and natural killer cells was recently found to cause necroptosis (programmed necrosis) via LMP [19]. Granulysin, which interacts with lipids to cause disruption of membranes, has a broad-spectrum antimicrobial function and shows potent cytotoxic activity against tumor cells. Granulysin enters lysosomes of tumor cells and triggers release of cathepsin B, which in turn engages the mitochondrial pathway via cleavage of Bid. Thus, it appears that our immune system is armed with a weapon to _target lysosomes for the destruction of unwanted cells.

Safeguards of lysosomal membrane integrity

It has been suggested that the stability of the lysosomal membrane could be modulated in different ways, and that this could contribute to the determination of cell fate. An example from normal physiological conditions is the selection of B-lymphocytes in the germinal centers. B-lymphocytes with high affinity B-cell receptors are spared from apoptotic cell death by interaction with follicular dendritic cells, which confer resistance to LMP [69]. The underlying mechanism was not unraveled in this study, but molecules involved in the stabilization of the lysosomal membrane have been identified by others (see below). Furthermore, cancer cells often show various changes in lysosomal function as well as altered susceptibility to lysosome-mediated cell death. For example, activation of the Ras or Src oncogenes is associated with changes in the lysosomal distribution, density, size, ultrastructure, and content, all of which may influence membrane stability [24, 90, 91, 98].

Heat shock proteins

Heat shock proteins (Hsps) are molecular chaperones essential for cells’ ability to cope with environmental stress [126]. Interestingly, Hsp70 is found at the lysosomes of many tumor cells and stressed cells, and has been shown to prevent LMP induced by TNF-α, etoposide, H2O2, or UVB irradiation [27, 127, 128]. Notably, Hsp70 is frequently overexpressed in tumors, and downregulation of Hsp70 in breast, pancreatic, or colon cancer cells leads to LMP and cathepsin-mediated cell death without any external death stimuli [27, 129], suggesting that the tumorigenic potential of Hsp70 could, in part, be due to stabilization of lysosomes. Hsp70 may prevent lysosomal membrane permeabilization by scavenging of lysosomal free iron and blocking of oxidative events [128, 130]. Moreover, it is tempting to speculate that Hsp70, which has been shown to interact with Bax and prevent its translocation to mitochondria [131, 132], could interfere with Bax-induced LMP.

In addition, Hsp70-2 can prevent permeabilization of the lysosomal membrane [133]. In this case, the protective effect depends on Hsp70-2-mediated upregulation of lens epithelium-derived growth factor (LEDGF). Knockdown of LEDGF in cancer cells induces destabilization of lysosomal membranes and cathepsin-mediated cell death, while ectopic expression stabilizes lysosomes and prevents cancer cell death. However, as LEDGF has not been detected in lysosomes, the protective mechanism remains obscure.

Bcl-2 proteins

Anti-apoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family are well-known regulators of mitochondrial membrane permeabilization, which, during recent years, have gained attention as possible modulators of lysosomal membrane stability [49, 50, 66, 134, 135]. Our finding that LMP may be induced by Bax is supported by the fact that overexpression of Bcl-2 prevents lysosomal destabilization [66, 134, 135]. In two of these studies, it was suggested that Bcl-2 stabilizes lysosomes by preventing activation of PLA2 [134, 135]. However, it is tempting to speculate that the protective effect of Bcl-2 is, at least in part, due to neutralization of pro-apoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family. The theory that anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins are safeguards of lysosomal membrane integrity is supported by data from Gregory Gores and co-workers [49, 50]. In these studies, Mcl-1 and Bcl-XL prevented LMP induced by TRAIL and free fatty acids, respectively. In both cases, Bax was activated and translocated from the cytosol to lysosomes upon apoptosis induction. Furthermore, overexpression of Mcl-1 and Bcl-XL, as well as siRNA-mediated downregulation of Bax, stabilized the lysosomal membrane.

Antioxidants

As described previously, ROS may compromise the integrity of lysosomes via peroxidation of membrane lipids. A variety of protective mechanisms have evolved to scavenge ROS and protect cells from their adverse effects; these are collectively known as the cell’s antioxidant defense. The defense mechanisms include low-molecular-weight antioxidants, for example vitamins C and E, coenzyme Q10, and glutathione, as well as antioxidant enzymes, such as glutathione peroxidase, catalase, and superoxide dismutase [136]. Vitamin E, a lipid soluble antioxidant that protects from lipid peroxidation [137], can prevent lysosomal release [5, 138]. Moreover, LMP induced by N-(4-hydroxyphenyl) retinamide or inhibitors of the vacuolar ATPase can be abrogated by increasing the amount of intracellular cysteine, which alters the redox balance [82, 83].

Furthermore, iron-binding proteins may serve to mitigate oxidant-induced LMP, as intralysosomal free iron can generate highly reactive hydroxyl radicals, leading to peroxidation of membrane lipids. Indeed, a number of studies have demonstrated that iron-binding proteins such as ferritin and metallothionein can reduce lysosomal leakage and cell death [84, 85, 139]. As mentioned above, also Hsp70 can bind intralysosomal redox-active iron and may, in that way, protect the lysosomal membrane from free-radical attack and permeabilization [128, 130].

Cholesterol and sphingomyelin

Cholesterol may play an important role in the maintenance of lysosomal membrane stability. It has long been known that addition of cholesterol to lysosomes reduces their permeability [140]. Accordingly, a reduced lysosomal membrane cholesterol level is associated with increased permeability to protons and potassium ions; this, in turn, causes an osmotic imbalance and destabilization of the lysosomal membrane [141–143]. Sphingomyelin affects the membrane fluidity by acting as a scaffold for incorporation of cholesterol [144, 145]. Exogenous sphingomyelin, as well as the sphingomyelin derivative 3-O-methylsphingomyelin, have been shown to accumulate in the lysosomal membrane and protect from lysosomal membrane disruption in response to TNF-α and lysosomal photosensitizers [78]. Thus, apoptosis-associated conversion of sphingomyelin into sphingosine (Fig. 4), a promoter of LMP, appears to have a dual negative effect on lysosomal membrane integrity.

Lysosome-associated membrane protein-1 and -2

The lysosomal membrane contains highly glycosylated proteins whose complex intralumenal carbohydrate side chains form a coat on the inner surface of the membrane. It has been suggested that these glycoproteins serve as a barrier against the hydrolytic activity of the lysosomal enzymes and thereby prevent accidental release of lysosomal constituents into the cytosol. Lysosome-associated membrane protein-1 (LAMP)-1 and -2, which constitute ~50% of the lysosomal membrane proteins [146, 147], can modulate the sensitivity of the lysosomal membrane to an apoptotic insult [98]. Oncogene-induced reduction in LAMP-1 and -2 can be caused by cathepsin B overexpression and is associated with increased susceptibility to LMP in response to photo-oxidation and the anti-cancer drug siramesine. The authors of that finding speculate that upregulation of lamp-1 and -2 mRNA, which has been observed in various human cancers [148, 149], might be an attempt to compensate for the deleterious effect of the reduced half-life of LAMP-1 and -2 in cancer cells overexpressing lysosomal cysteine cathepsins.

Conclusion

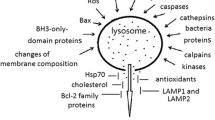

A growing body of evidence suggests that apoptosis is generally associated with LMP, occurring either as a triggering early event or an amplifying late event. With the wider acceptance of lysosomes as part of the signaling cascade leading to apoptotic cell death, the molecular mechanisms governing LMP have received increased attention. As outlined above, there are many proteinaceous and non-proteinaceous factors, including Bcl-2 family proteins, ROS, caspases, cathepsins, cholesterol, and Hsps, that influence the stability of the lysosomal membrane, and their individual importance appears to depend on the cell type and death stimulus (Fig. 5). However, the main mechanism responsible for apoptosis-associated LMP, if any, remains to be identified. A deeper understanding of the regulation of LMP and other apoptosis signaling events could enable the development of novel therapies for diseases associated with excessive or insufficient apoptosis such as neurodegenerative disorders and cancer, respectively.

Factors regulating lysosomal membrane permeabilization. This schematic presents a number of factors that may be responsible for lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP). The relative importance of each mechanism likely depends on the cell type and death stimulus. Mechanisms that are believed to safeguard lysosomal integrity and protect from lysosome-mediated cell death are also shown. “Changes in membrane lipid composition” includes membrane destabilizing factors such as phospholipase A2 and sphingosine, as well as LPM protective substances e.g., cholesterol and sphingomyelin. Abbreviations: JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; LAPF, lysosome-associated apoptosis-inducing protein containing the pleckstrin homology and FYVE domains; Hsp, heat shock protein; ROS, reactive oxygen species; ANT, adenine nucleotide translocator; Ahr, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; LEDGF, lens epithelium-derived growth factor; LAMP, lysosome-associated membrane protein

Abbreviations

- Ahr:

-

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- ANT:

-

Adenine nucleotide translocator

- apoE:

-

Apolipoprotein E

- BH3:

-

Bcl-2 homology 3

- Hsp:

-

Heat shock protein

- JNK:

-

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- LAMP:

-

Lysosome-associated membrane protein

- LAPF:

-

Lysosome-associated apoptosis-inducing protein containing the pleckstrin homology and FYVE domains

- LEDGF:

-

Lens epithelium-derived growth factor

- LMP:

-

Lysosomal membrane permeabilization

- PI3K:

-

Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase

- PLA2:

-

Phospholipase A2

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- siRNA:

-

Small-interfering RNA

- SMase:

-

Sphingomyelinase

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

- TRAIL:

-

Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis inducing ligand

- UV:

-

Ultraviolet

References

de Duve C, Pressman BC, Gianetto R, Wattiaux R, Applemans F (1955) Tissue fractionation studies. 6. Intracellular distribution patterns of enzymes in rat-liver tissue. Biochem J 60:604–617

de Duve C (1983) Lysosomes revisited. Eur J Biochem 137:391–397

Turk B, Stoka V (2007) Protease signalling in cell death: caspases versus cysteine cathepsins. FEBS Lett 581:2761–2767

de Duve C (1959) Lysosomes, a new group of cytoplasmic particles. In: Hayashi T (ed) Subcellular particles. Ronald Press, New York, pp 128–159

Roberg K, Öllinger K (1998) Oxidative stress causes relocation of the lysosomal enzyme cathepsin D with ensuing apoptosis in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Am J Pathol 152:1151–1156

Deiss LP, Galinka H, Berissi H, Cohen O, Kimchi A (1996) Cathepsin D protease mediates programmed cell death induced by interferon-γ, Fas/APO-1 and TNF-α. EMBO J 15:3861–3870

Wu GS, Saftig P, Peters C, El-Deiry WS (1998) Potential role for cathepsin D in p53-dependent tumor suppression and chemosensitivity. Oncogene 16:2177–2183

Brunk UT, Dalen H, Roberg K, Hellquist HB (1997) Photo-oxidative disruption of lysosomal membranes causes apoptosis of cultured human fibroblasts. Free Radic Biol Med 23:616–626

Brunk UT, Svensson I (1999) Oxidative stress, growth factor starvation and Fas activation may all cause apoptosis through lysosomal leak. Redox Rep 4:3–11

Kågedal K, Zhao M, Svensson I, Brunk UT (2001) Sphingosine-induced apoptosis is dependent on lysosomal proteases. Biochem J 359:335–343

Li W, Yuan XM, Nordgren G et al (2000) Induction of cell death by the lysosomotropic detergent MSDH. FEBS Lett 470:35–39

Antunes F, Cadenas E, Brunk UT (2001) Apoptosis induced by exposure to a low steady-state concentration of H2O2 is a consequence of lysosomal rupture. Biochem J 356:549–555

Boya P, Kroemer G (2008) Lysosomal membrane permeabilization in cell death. Oncogene 27:6434–6451

Chwieralski CE, Welte T, Bühling F (2006) Cathepsin-regulated apoptosis. Apoptosis 11:143–149

Guicciardi ME, Leist M, Gores GJ (2004) Lysosomes in cell death. Oncogene 23:2881–2890

Stoka V, Turk V, Turk B (2007) Lysosomal cysteine cathepsins: signaling pathways in apoptosis. Biol Chem 388:555–560

Kirkegaard T, Jäättelä M (2009) Lysosomal involvement in cell death and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 1793:746–754

Kroemer G, Jaattela M (2005) Lysosomes and autophagy in cell death control. Nat Rev Cancer 5:886–897

Zhang H, Zhong C, Shi L, Guo Y, Fan Z (2009) Granulysin induces cathepsin B release from lysosomes of _target tumor cells to attack mitochondria through processing of bid leading to Necroptosis. J Immunol 182:6993–7000

Roberg K, Kågedal K, Öllinger K (2002) Microinjection of cathepsin D induces caspase-dependent apoptosis in fibroblasts. Am J Pathol 161:89–96

Schestkowa O, Geisel D, Jacob R, Hasilik A (2007) The catalytically inactive precursor of cathepsin D induces apoptosis in human fibroblasts and HeLa cells. J Cell Biochem 101:1558–1566

Bivik CA, Larsson PK, Kågedal KM, Rosdahl IK, Öllinger KM (2006) UVA/B-induced apoptosis in human melanocytes involves translocation of cathepsins and Bcl-2 family members. J Invest Dermatol 126:1119–1127

Nilsson E, Ghassemifar R, Brunk UT (1997) Lysosomal heterogeneity between and within cells with respect to resistance against oxidative stress. Histochem J 29:857–865

Ono K, Kim SO, Han J (2003) Susceptibility of lysosomes to rupture is a determinant for plasma membrane disruption in tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced cell death. Mol Cell Biol 23:665–676

Blomgran R, Zheng L, Stendahl O (2007) Cathepsin-cleaved Bid promotes apoptosis in human neutrophils via oxidative stress-induced lysosomal membrane permeabilization. J Leukoc Biol 81:1213–1223

Kågedal K, Johansson AC, Johansson U et al (2005) Lysosomal membrane permeabilization during apoptosis-involvement of Bax? Int J Exp Pathol 86:309–321

Nylandsted J, Gyrd-Hansen M, Danielewicz A et al (2004) Heat shock protein 70 promotes cell survival by inhibiting lysosomal membrane permeabilization. J Exp Med 200:425–435

Miao Q, Sun Y, Wei T et al (2008) Chymotrypsin B cached in rat liver lysosomes and involved in apoptotic regulation through a mitochondrial pathway. J Biol Chem 283:8218–8228

Nilsson C, Johansson U, Johansson AC, Kågedal K, Öllinger K (2006) Cytosolic acidification and lysosomal alkalinization during TNF-alpha induced apoptosis in U937 cells. Apoptosis 11:1149–1159

Mirnikjoo B, Balasubramanian K, Schroit AJ (2009) Mobilization of lysosomal calcium regulates the externalization of phosphatidylserine during apoptosis. J Biol Chem 284:6918–6923

Werneburg NW, Guicciardi ME, Bronk SF, Gores GJ (2002) Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-associated lysosomal permeabilization is cathepsin B dependent. Am J Physiol-Gastroint Liver Physiol 283:G947–G956

Bidère N, Lorenzo HK, Carmona S et al (2003) Cathepsin D triggers Bax activation, resulting in selective apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) relocation in T lymphocytes entering the early commitment phase to apoptosis. J Biol Chem 278:31401–31411

Birk AV, Dubovi EJ, Cohen-Gould L, Donis R, Szeto HH (2008) Cytoplasmic vacuolization responses to cytopathic bovine viral diarrhoea virus. Virus Res 132:76–85

Di Piazza M, Mader C, Geletneky K et al (2007) Cytosolic activation of cathepsins mediates parvovirus H-1-induced killing of cisplatin and TRAIL-resistant glioma cells. J Virol 81:4186–4198

Kaznelson DW, Bruun S, Monrad A et al (2004) Simultaneous human papilloma virus type 16 E7 and cdk inhibitor p21 expression induces apoptosis and cathepsin B activation. Virology 320:301–312

Laforge M, Petit F, Estaquier J, Senik A (2007) Commitment to apoptosis in CD4+ T lymphocytes productively infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is initiated by lysosomal membrane permeabilization, itself induced by the isolated expression of the viral protein Nef. J Virol 81:11426–11440

O’Sullivan MP, O’Leary S, Kelly DM, Keane J (2007) A caspase-independent pathway mediates macrophage cell death in response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Infect Immun 75:1984–1993

Prince LR, Bianchi SM, Vaughan KM et al (2008) Subversion of a lysosomal pathway regulating neutrophil apoptosis by a major bacterial toxin, pyocyanin. J Immunol 180:3502–3511

Sandvig K (2003) Transport of toxins across intracellular membranes. In: Burns DL, Barbier JT, Iglewski BH (eds) Bacterial protein toxins. ASM, Washington, pp 157–172

Sandvig K, Olsnes S (1980) Diphtheria toxin entry into cells is facilitated by low pH. J Cell Biol 87:828–832

Donovan JJ, Simon MI, Draper RK, Montal M (1981) Diphtheria toxin forms transmembrane channels in planar lipid bilayers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 78:172–176

Kagan BL, Finkelstein A, Colombini M (1981) Diphtheria toxin fragment forms large pores in phospholipid bilayer membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 78:4950–4954

Boquet P, Duflot E (1982) Tetanus toxin fragment forms channels in lipid vesicles at low pH. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 79:7614–7618

Donovan JJ, Middlebrook JL (1986) Ion-conducting channels produced by botulinum toxin in planar lipid membranes. Biochemistry 25:2872–2876

Blaustein RO, Koehler TM, Collier RJ, Finkelstein A (1989) Anthrax toxin: channel-forming activity of protective antigen in planar phospholipid bilayers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 86:2209–2213

Muchmore SW, Sattler M, Liang H et al (1996) X-ray and NMR structure of human Bcl-xL, an inhibitor of programmed cell death. Nature 381:335–341

Suzuki M, Youle RJ, Tjandra N (2000) Structure of Bax: coregulation of dimer formation and intracellular localization. Cell 103:645–654

Feldstein AE, Werneburg NW, Canbay A et al (2004) Free fatty acids promote hepatic lipotoxicity by stimulating TNF-alpha expression via a lysosomal pathway. Hepatology 40:185–194

Feldstein AE, Werneburg NW, Li Z, Bronk SF, Gores GJ (2006) Bax inhibition protects against free fatty acid-induced lysosomal permeabilization. Am J Physiol-Gastroint Liver Physiol 290:G1339–G1346

Werneburg NW, Guicciardi ME, Bronk SF, Kaufmann SH, Gores GJ (2007) Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand activates a lysosomal pathway of apoptosis that is regulated by Bcl-2 proteins. J Biol Chem 282:28960–28970

Castino R, Peracchio C, Salini A et al (2009) Chemotherapy drug response in ovarian cancer cells strictly depends on a cathepsin D—bax activation loop. J Cell Mol Med 13:1096–1109

Werneburg NW, Guicciardi ME, Yin XM, Gores GJ (2004) TNF-alpha-mediated lysosomal permeabilization is FAN and caspase 8/Bid dependent. Am J Physiol-Gastroint Liver Physiol 287:G436–G443

Youle RJ, Strasser A (2008) The BCL-2 protein family: opposing activities that mediate cell death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9:47–59

Boya P, Andreau K, Poncet D et al (2003) Lysosomal membrane permeabilization induces cell death in a mitochondrion-dependent fashion. J Exp Med 197:1323–1334

Yuan XM, Li W, Dalen H et al (2002) Lysosomal destabilization in p53-induced apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:6286–6291

Li N, Zheng Y, Chen W et al (2007) Adaptor protein LAPF recruits phosphorylated p53 to lysosomes and triggers lysosomal destabilization in apoptosis. Cancer Res 67:11176–11185

Chen W, Li N, Chen T et al (2005) The lysosome-associated apoptosis-inducing protein containing the pleckstrin homology (PH) and FYVE domains (LAPF), representative of a novel family of PH and FYVE domain-containing proteins, induces caspase-independent apoptosis via the lysosomal-mitochondrial pathway. J Biol Chem 280:40985–40995

Gowran A, Campbell VA (2008) A role for p53 in the regulation of lysosomal permeability by delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol in rat cortical neurones: implications for neurodegeneration. J Neurochem 105:1513–1524

Fogarty MP, McCormack RM, Noonan J, Murphy D, Gowran A, Campbell VA (2008) A role for p53 in the beta-amyloid-mediated regulation of the lysosomal system. Neurobiol Aging. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.09.018

Chipuk JE, Kuwana T, Bouchier-Hayes L et al (2004) Direct activation of Bax by p53 mediates mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and apoptosis. Science 303:1010–1014

Mihara M, Erster S, Zaika A et al (2003) p53 has a direct apoptogenic role at the mitochondria. Mol Cell 11:577–590

Oda E, Ohki R, Murasawa H et al (2000) Noxa, a BH3-only member of the Bcl-2 family and candidate mediator of p53-induced apoptosis. Science 288:1053–1058

Yu J, Zhang L, Hwang PM, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B (2001) PUMA induces the rapid apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells. Mol Cell 7:673–682

Nakano K, Vousden KH (2001) PUMA, a novel proapoptotic gene, is induced by p53. Mol Cell 7:683–694

Wäster PK, Öllinger KM (2009) Redox-dependent translocation of p53 to mitochondria or nucleus in human melanocytes after UVA- and UVB-induced apoptosis. J Invest Dermatol 129:1769–1781

Paris C, Bertoglio J, Bréard J (2007) Lysosomal and mitochondrial pathways in miltefosine-induced apoptosis in U937 cells. Apoptosis 12:1257–1267

Guicciardi ME, Deussing J, Miyoshi H et al (2000) Cathepsin B contributes to TNF-α-mediated hepatocyte apoptosis by promoting mitochondrial release of cytochrome c. J Clin Invest 106:1127–1137

Gyrd-Hansen M, Farkas T, Fehrenbacher N et al (2006) Apoptosome-independent activation of the lysosomal cell death pathway by caspase-9. Mol Cell Biol 26:7880–7891

van Nierop K, Muller FJ, Stap J, Van Noorden CJ, van Eijk M, de Groot C (2006) Lysosomal destabilization contributes to apoptosis of germinal center B-lymphocytes. J Histochem Cytochem 54:1425–1435

Huang WC, Lin YS, Chen CL, Wang CY, Chiu WH, Lin CF (2009) Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta mediates endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced lysosomal apoptosis in leukemia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 329:524–531

Guicciardi ME, Bronk SF, Werneburg NW, Gores GJ (2007) cFLIPL prevents TRAIL-induced apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by inhibiting the lysosomal pathway of apoptosis. Am J Physiol-Gastroint Liver Physiol 292:G1337–G1346

Liu N, Raja SM, Zazzeroni F et al (2003) NF-kappaB protects from the lysosomal pathway of cell death. EMBO J 22:5313–5322

Yap YW, Whiteman M, Bay BH et al (2006) Hypochlorous acid induces apoptosis of cultured cortical neurons through activation of calpains and rupture of lysosomes. J Neurochem 98:1597–1609

Yamashima T, Saido TC, Takita M et al (1996) Transient brain ischaemia provokes Ca2+, PIP2 and calpain responses prior to delayed neuronal death in monkeys. Eur J Neurosci 8:1932–1944

Yamashima T, Tonchev AB, Tsukada T et al (2003) Sustained calpain activation associated with lysosomal rupture executes necrosis of the postischemic CA1 neurons in primates. Hippocampus 13:791–800

Windelborn JA, Lipton P (2008) Lysosomal release of cathepsins causes ischemic damage in the rat hippocampal slice and depends on NMDA-mediated calcium influx, arachidonic acid metabolism, and free radical production. J Neurochem 106:56–69

Yamashima T, Kohda Y, Tsuchiya K et al (1998) Inhibition of ischaemic hippocampal neuronal death in primates with cathepsin B inhibitor CA-074: a novel strategy for neuroprotection based on ‘calpain-cathepsin hypothesis’. Eur J Neurosci 10:1723–1733

Caruso JA, Mathieu PA, Reiners JJ Jr (2005) Sphingomyelins suppress the _targeted disruption of lysosomes/endosomes by the photosensitizer NPe6 during photodynamic therapy. Biochem J 392:325–334

Kessel D, Luo Y, Mathieu P, Reiners JJ Jr (2000) Determinants of the apoptotic response to lysosomal photodamage. Photochem Photobiol 71:196–200

Reiners JJ Jr, Caruso JA, Mathieu P, Chelladurai B, Yin XM, Kessel D (2002) Release of cytochrome c and activation of pro-caspase-9 following lysosomal photodamage involves Bid cleavage. Cell Death Differ 9:934–944

Öllinger K, Brunk UT (1995) Cellular injury induced by oxidative stress is mediated through lysosomal damage. Free Radic Biol Med 19:565–574

Vene R, Arena G, Poggi A et al (2007) Novel cell death pathways induced by N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)retinamide: therapeutic implications. Mol Cancer Ther 6:286–298

De Milito A, Iessi E, Logozzi M et al (2007) Proton pump inhibitors induce apoptosis of human B-cell tumors through a caspase-independent mechanism involving reactive oxygen species. Cancer Res 67:5408–5417

Garner B, Li W, Roberg K, Brunk UT (1997) On the cytoprotective role of ferritin in macrophages and its ability to enhance lysosomal stability. Free Radic Res 27:487–500

Persson HL, Nilsson KJ, Brunk UT (2001) Novel cellular defenses against iron and oxidation: ferritin and autophagocytosis preserve lysosomal stability in airway epithelium. Redox Rep 6:57–63

Persson HL, Yu Z, Tirosh O, Eaton JW, Brunk UT (2003) Prevention of oxidant-induced cell death by lysosomotropic iron chelators. Free Radic Biol Med 34:1295–1305

Persson HL, Kurz T, Eaton JW, Brunk UT (2005) Radiation-induced cell death: importance of lysosomal destabilization. Biochem J 389:877–884

Yu Z, Persson HL, Eaton JW, Brunk UT (2003) Intralysosomal iron: a major determinant of oxidant-induced cell death. Free Radic Biol Med 34:1243–1252

Persson HL (2005) Iron-dependent lysosomal destabilization initiates silica-induced apoptosis in murine macrophages. Toxicol Lett 159:124–133

Brown WJ, DeWald DB, Emr SD, Plutner H, Balch WE (1995) Role for phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in the sorting and transport of newly synthesized lysosomal enzymes in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol 130:781–796

Mousavi SA, Brech A, Berg T, Kjeken R (2003) Phosphoinositide 3-kinase regulates maturation of lysosomes in rat hepatocytes. Biochem J 372:861–869

Fehrenbacher N, Philips M (2009) Intracellular signaling: peripatetic Ras. Curr Biol 19:R454–R457

Fehrenbacher N, Gyrd-Hansen M, Poulsen B et al (2004) Sensitization to the lysosomal cell death pathway upon immortalization and transformation. Cancer Res 64:5301–5310

Madge LA, Li J-H, Choi J, Pober JS (2003) Inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase sensitizes vascular endothelial cells to cytokine-initiated cathepsin-dependent apoptosis. J Biol Chem 278:21295–21306

Dietrich N, Thastrup J, Holmberg C et al (2004) JNK2 mediates TNF-induced cell death in mouse embryonic fibroblasts via regulation of both caspase and cathepsin protease pathways. Cell Death Differ 11:301–313

Bivik C, Öllinger K (2008) JNK mediates UVB-induced apoptosis upstream lysosomal membrane permeabilization and Bcl-2 family proteins. Apoptosis 13:1111–1120

Fogarty MP, Downer EJ, Campbell V (2003) A role for c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 (JNK1), but not JNK2, in the beta-amyloid-mediated stabilization of protein p53 and induction of the apoptotic cascade in cultured cortical neurons. Biochem J 371:789–798

Fehrenbacher N, Bastholm L, Kirkegaard-Sorensen T et al (2008) Sensitization to the lysosomal cell death pathway by oncogene-induced down-regulation of lysosome-associated membrane proteins 1 and 2. Cancer Res 68:6623–6633

Zhao HF, Wang X, Zhang GJ (2005) Lysosome destabilization by cytosolic extracts, putative involvement of Ca(2+)/phospholipase C. FEBS Lett 579:1551–1556

Wang X, Zhao HF, Zhang GJ (2006) Mechanism of cytosol phospholipase C and sphingomyelinase-induced lysosome destabilization. Biochimie 88:913–922

Wang JW, Sun L, Hu JS, Li YB, Zhang GJ (2006) Effects of phospholipase A2 on the lysosomal ion permeability and osmotic sensitivity. Chem Phys Lipids 144:117–126

Wang X, Wang LL, Zhang GJ (2006) Guanosine 5′-[gamma-thio]triphosphate-mediated activation of cytosol phospholipase C caused lysosomal destabilization. J Membr Biol 211:55–63

Zhang G, Yi YP, Zhang GJ (2006) Effects of arachidonic acid on the lysosomal ion permeability and osmotic stability. J Bioenerg Biomembr 38:75–82

Hu JS, Li YB, Wang JW, Sun L, Zhang GJ (2007) Mechanism of lysophosphatidylcholine-induced lysosome destabilization. J Membr Biol 215:27–35

Yi YP, Wang X, Zhang G, Fu TS, Zhang GJ (2006) Phosphatidic acid osmotically destabilizes lysosomes through increased permeability to K+ and H+. Gen Physiol Biophys 25:149–160

Zhao M, Brunk UT, Eaton JW (2001) Delayed oxidant-induced cell death involves activation of phospholipase A2. FEBS Lett 509:399–404

Burlando B, Marchi B, Panfoli I, Viarengo A (2002) Essential role of Ca2+—dependent phospholipase A2 in estradiol-induced lysosome activation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 283:C1461–C1468

Marone G, Fimiani B, Torella G, Poto S, Bianco P, Condorelli M (1983) Possible role of arachidonic acid and of phospholipase A2 in the control of lysosomal enzyme release from human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Clin Lab Immunol 12:111–116

Marchi B, Burlando B, Moore MN, Viarengo A (2004) Mercury- and copper-induced lysosomal membrane destabilisation depends on [Ca2+]i dependent phospholipase A2 activation. Aquat Toxicol 66:197–204

Schutze S, Machleidt T, Adam D et al (1999) Inhibition of receptor internalization by monodansylcadaverine selectively blocks p55 tumor necrosis factor receptor death domain signaling. J Biol Chem 274:10203–10212

Parent N, Winstall E, Beauchemin M, Paquet C, Poirier GG, Bertrand R (2009) Proteomic analysis of enriched lysosomes at early phase of camptothecin-induced apoptosis in human U-937 cells. J Proteomics 72:960–973

Zeidan YH, Hannun YA (2007) Activation of acid sphingomyelinase by protein kinase Cdelta-mediated phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 282:11549–11561

Ferlinz K, Linke T, Bartelsen O, Weiler M, Sandhoff K (1999) Stimulation of lysosomal sphingomyelin degradation by sphingolipid activator proteins. Chem Phys Lipids 102:35–43

Yang AJ, Chandswangbhuvana D, Shu T, Henschen A, Glabe CG (1999) Intracellular accumulation of insoluble, newly synthesized abetan-42 in amyloid precursor protein-transfected cells that have been treated with Abeta1–42. J Biol Chem 274:20650–20656

Zheng L, Kågedal K, Dehvari N et al (2009) Oxidative stress induces macroautophagy of amyloid beta-protein and ensuing apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med 46:422–429

Soreghan B, Kosmoski J, Glabe C (1994) Surfactant properties of Alzheimer’s A beta peptides and the mechanism of amyloid aggregation. J Biol Chem 269:28551–28554

Lomakin A, Chung DS, Benedek GB, Kirschner DA, Teplow DB (1996) On the nucleation and growth of amyloid beta-protein fibrils: detection of nuclei and quantitation of rate constants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93:1125–1129

Forster S, Scarlett L, Lloyd JB (1987) The effect of lysosomotropic detergents on the permeability properties of the lysosome membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta 924:452–457

Lin H, Bhatia R, Lal R (2001) Amyloid beta protein forms ion channels: implications for Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology. FASEB J 15:2433–2444

Quist A, Doudevski I, Lin H et al (2005) Amyloid ion channels: a common structural link for protein-misfolding disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:10427–10432

Ji ZS, Miranda RD, Newhouse YM, Weisgraber KH, Huang Y, Mahley RW (2002) Apolipoprotein E4 potentiates amyloid beta peptide-induced lysosomal leakage and apoptosis in neuronal cells. J Biol Chem 277:21821–21828

Ji ZS, Mullendorff K, Cheng IH, Miranda RD, Huang Y, Mahley RW (2006) Reactivity of apolipoprotein E4 and amyloid beta peptide: lysosomal stability and neurodegeneration. J Biol Chem 281:2683–2692

Caruso JA, Mathieu PA, Joiakim A, Zhang H, Reiners JJ Jr (2006) Aryl hydrocarbon receptor modulation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced apoptosis and lysosomal disruption in a hepatoma model that is caspase-8-independent. J Biol Chem 281:10954–10967

Caruso JA, Mathieu PA, Joiakim A et al (2004) Differential susceptibilities of murine hepatoma 1c1c7 and Tao cells to the lysosomal photosensitizer NPe6: influence of aryl hydrocarbon receptor on lysosomal fragility and protease contents. Mol Pharmacol 65:1016–1028

Vancompernolle K, Van Herreweghe F, Pynaert G et al (1998) Atractyloside-induced release of cathepsin B, a protease with caspase-processing activity. FEBS Lett 438:150–158

Jäättelä M (1999) Escaping cell death: survival proteins in cancer. Exp Cell Res 248:30–43

Bivik C, Rosdahl I, Öllinger K (2007) Hsp70 protects against UVB induced apoptosis by preventing release of cathepsins and cytochrome c in human melanocytes. Carcinogenesis 28:537–544

Doulias PT, Kotoglou P, Tenopoulou M et al (2007) Involvement of heat shock protein-70 in the mechanism of hydrogen peroxide-induced DNA damage: the role of lysosomes and iron. Free Radic Biol Med 42:567–577

Dudeja V, Mujumdar N, Phillips P et al (2009) Heat shock protein 70 inhibits apoptosis in cancer cells through simultaneous and independent mechanisms. Gastroenterology 136:1772–1782

Kurz T, Brunk UT (2009) Autophagy of HSP70 and chelation of lysosomal iron in a non-redox-active form. Autophagy 5:93–95

Gotoh T, Terada K, Oyadomari S, Mori M (2004) hsp70-DnaJ chaperone pair prevents nitric oxide- and CHOP-induced apoptosis by inhibiting translocation of Bax to mitochondria. Cell Death Differ 11:390–402

Stankiewicz AR, Lachapelle G, Foo CP, Radicioni SM, Mosser DD (2005) Hsp70 inhibits heat-induced apoptosis upstream of mitochondria by preventing Bax translocation. J Biol Chem 280:38729–38739

Daugaard M, Kirkegaard-Sørensen T, Ostenfeld MS et al (2007) Lens epithelium-derived growth factor is an Hsp70–2 regulated guardian of lysosomal stability in human cancer. Cancer Res 67:2559–2567

Zhao M, Eaton JW, Brunk UT (2000) Protection against oxidant-mediated lysosomal rupture: a new anti-apoptotic activity of Bcl-2? FEBS Lett 485:104–108

Zhao M, Eaton JW, Brunk UT (2001) Bcl-2 phosphorylation is required for inhibition of oxidative stress-induced lysosomal leak and ensuing apoptosis. FEBS Lett 509:405–412

Halliwell B (1999) Antioxidant defence mechanisms: from the beginning to the end (of the beginning). Free Radic Res 31:261–272

Yoshida Y, Saito Y, Jones LS, Shigeri Y (2007) Chemical reactivities and physical effects in comparison between tocopherols and tocotrienols: physiological significance and prospects as antioxidants. J Biosci Bioeng 104:439–445

Mukherjee AK, Ghosal SK, Maity CR (1997) Lysosomal membrane stabilization by alpha-tocopherol against the damaging action of Vipera russelli venom phospholipase A2. Cell Mol Life Sci 53:152–155

Baird SK, Kurz T, Brunk UT (2006) Metallothionein protects against oxidative stress-induced lysosomal destabilization. Biochem J 394:275–283

Fouchier F, Mego JL, Dang J, Simon C (1983) Thyroid lysosomes: the stability of the lysosomal membrane. Eur J Cell Biol 30:272–278

Deng D, Jiang N, Hao SJ, Sun H, Zhang GJ (2009) Loss of membrane cholesterol influences lysosomal permeability to potassium ions and protons. Biochim Biophys Acta 1788:470–476

Jadot M, Andrianaivo F, Dubois F, Wattiaux R (2001) Effects of methylcyclodextrin on lysosomes. Eur J Biochem 268:1392–1399

Hao SJ, Hou JF, Jiang N, Zhang GJ (2008) Loss of membrane cholesterol affects lysosomal osmotic stability. Gen Physiol Biophys 27:278–283

Ridgway ND (2000) Interactions between metabolism and intracellular distribution of cholesterol and sphingomyelin. Biochim Biophys Acta 1484:129–141

Simons K, Ikonen E (2000) How cells handle cholesterol. Science 290:1721–1726

Eskelinen EL (2006) Roles of LAMP-1 and LAMP-2 in lysosome biogenesis and autophagy. Mol Aspects Med 27:495–502

Fukuda M (1991) Lysosomal membrane glycoproteins. Structure, biosynthesis, and intracellular trafficking. J Biol Chem 266:21327–21330

Furuta K, Ikeda M, Nakayama Y et al (2001) Expression of lysosome-associated membrane proteins in human colorectal neoplasms and inflammatory diseases. Am J Pathol 159:449–455

Ozaki K, Nagata M, Suzuki M et al (1998) Isolation and characterization of a novel human lung-specific gene homologous to lysosomal membrane glycoproteins 1 and 2: significantly increased expression in cancers of various tissues. Cancer Res 58:3499–3503

Acknowledgments

We thank Lotta Hellström and Fredrik Jerhammar for critical reading of the manuscript.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Johansson, AC., Appelqvist, H., Nilsson, C. et al. Regulation of apoptosis-associated lysosomal membrane permeabilization. Apoptosis 15, 527–540 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10495-009-0452-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10495-009-0452-5