Thoth

Overview

One of the most complex deities of the ancient Egyptian pantheon, Thoth was the god of the moon, medicine, science, magic, judgement, and writing. A figure of tremendous importance, he held significant roles in many central myths.

An ibis-headed ceramic figure of Thoth (664-343 BCE)

Brooklyn MuseumCC BY 3.0Thoth originated far from the religious centers that spawned the vast majority of the Egyptian pantheon. As a result, Thoth took on the role of the perpetual outsider; he was not the focus of any major myths, and his stories could often proven convoluted or vague. In many tales, he appeared without explanation. Despite Thoth’s strange position (or perhaps because of it), he held a key role in the Egyptian mythos and was respected by all.

Thoth’s popularity eventually grew beyond the confines of his native civilization. Following the decline of the ancient Egyptian religion, he lived on in the Greek religious tradition as Hermes, the messenger of the gods.

Etymology

As was common for Egyptian gods, the exact meaning of Thoth’s name was somewhat unclear. It is commonly thought that his name meant “He Who is Like the Ibis.”[1] The Egyptians knew him as Djehuty, and the Greeks knew him as Hermes.[2]

Many Egyptian city names were derived from the Greek names of the gods that were worshipped there. Hermopolis was so-called thanks to its position as Thoth’s center of worship.

Among Thoth’s many epithets were:

Attributes

An incredibly important deity to the Egyptians, Thoth represented many facets of reality. He was a god of the moon, science, wisdom, secret magics, and medicine. Thoth invented writing and was believed to be the patron of scribes.[5] As the messenger of the gods, he often served as Ra’s intermediary between the lands of the living and the dead.

As Ra’s most trusted advisor, Thoth was tasked with recording all that happened. A just and incorruptible bureaucrat, he was viewed as a judge without equal.[6]

More than a mere observer, Thoth was the enforcer of maat, or cosmic order. In this role, Thoth served as both consummate diplomat and merciless executioner.[7]

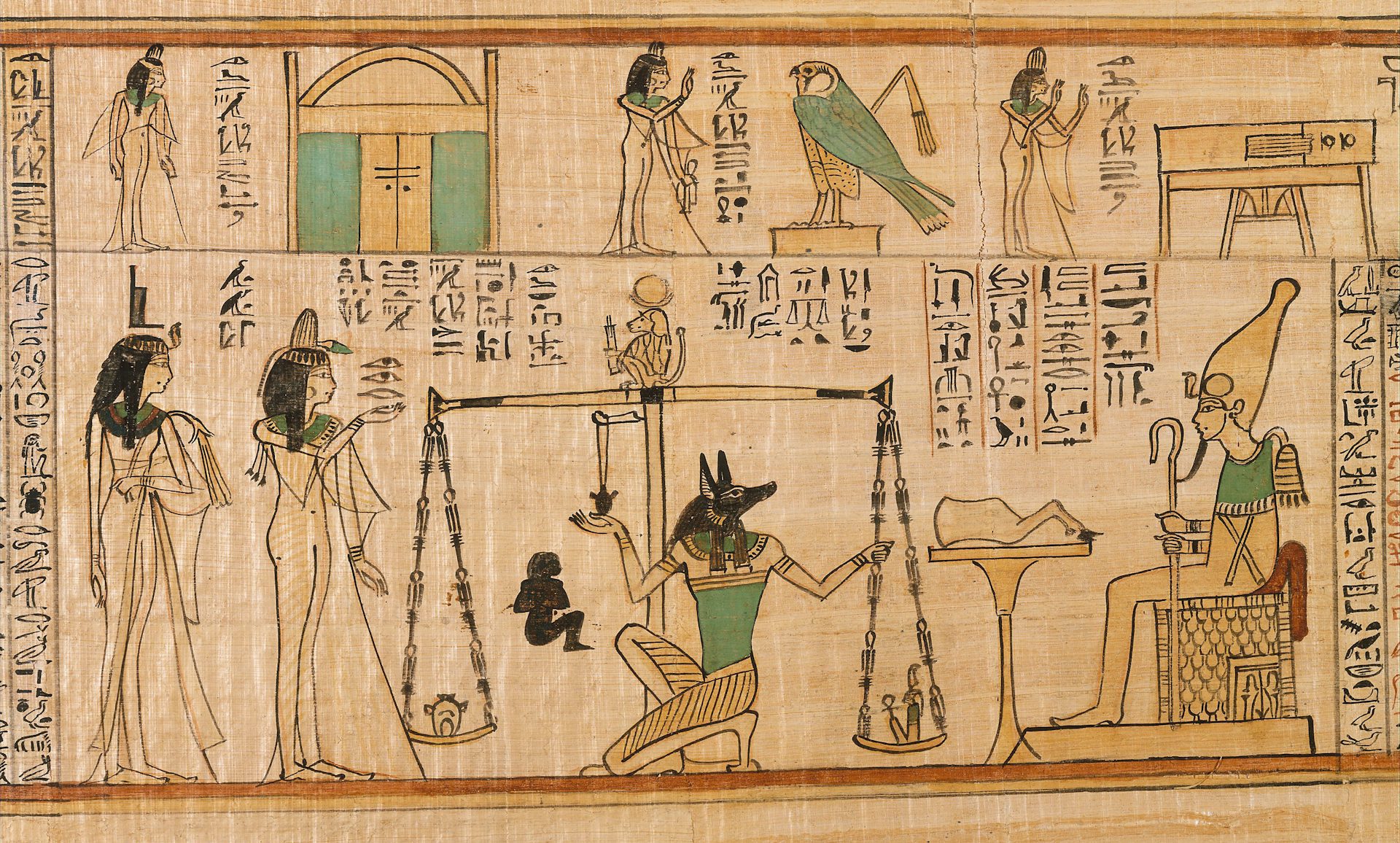

This scene from the Book of the Dead (c. 1050 BCE) demonstrates the weighing of the heart ceremony. Thoth (in his baboon form) can be seen at the top of the scale recording the result. The deity's headdress depicts the full and crescent moons.

The Metropolitan Museum of ArtPublic DomainThough Thoth appeared as both an ibis-headed man and a baboon in Egyptian mythology, his personality remained consistent across these representations. While Thoth’s baboon imagery predated his ibis-headed portrayals, the latter emerged as his primary depiction over time.[8]

Both of Thoth’s representations alluded to his status as a lunar deity. The ibis’s curved beak resembles a crescent moon, and as a baboon his head was often topped with a headdress depicting a full and crescent moon.[9]

Family

When discussing Egyptian mythology, it is easy to refer to it as a singular belief system. However, the reality was that each major city had its own interpretation. Hermopolis, the center of Thoth’s cult, never had the political clout of Memphis, Heliopolis, or Thebes, so Thoth existed alongside their divine families rather than being incorporated neatly into the divine bloodlines.[10]

Thoth’s Parentage

Several stories regarding Thoth’s parents, and due to the heterogenous style of worship found in Egypt, they all contradict one another:

A tale from Hermopolis held that Thoth had no parents, and was actually self-created.

Thoth may have been created by Ra, Atum, and Khepri, as he once declared “I am Thoth, the eldest son of Ra, whom Atum has fashioned, created from Khrepi.”[11]

In a lesser known tale, Thoth was said to be the son of Horus.

In a parallel mythology, Thoth had ties to both Horus and Set.[12]

Wives of Thoth

Depending upon the myth, Thoth was believed to have a number of different wives:

Maat (the goddess of justice and order)

Seshat (the goddess of writing)[13]

Nehemtawy (a goddess of which little is known)

It is possible that Thoth had more than one wife, as the ancient Egyptians permitted men to marry multiple women. However, the fact that some myths described Seshat as Thoth’s daughter indicates such multiplicity was most likely an artifact of parallel mythologies.

Marriage between close relations (such as first cousins) was not a taboo in ancient Egypt. Marriage between father and daughter, on the other hand, was regarded as inappropriate.[14]

Family Tree

Consorts

Wife

- Maat

Children

Daughter

- Seshat

Mythology

Thoth played a role in most major Egyptian stories, as well as several myths unique to Hermopolis. His sage advice and medical expertise usually arrived at a pivotal moment, altering the course of events for the better.

Hermopolian Origin Myth

While Thoth was a tremendously important deity throughout Egypt, he held particular significance in Hermopolis, which served as his center of worship.

A colossal baboon statue representing Thoth has been reconstructed at the el-Ashmunein archeological site. Under Roman rule, the city was named Hermopolis after the Greek god Hermes. This Greek deity was based off of Thoth, and his city served as the center of Thoth's cult.

Don McCradyCC BY-NC-ND 2.0For those living in Hermopolis, the pre-creation universe existed in the form of Nun—an infinite body of inert water. Nun was a difficult concept to fathom, so the Hermopolians divided Nun into 8 components, half male, half female. These eight deities were represented by frogs for the men, and snakes for the women and included:

Nun and Naunet: the boundless waters

Huh and Hauhet: infinity

Kuk and Kauket: darkness

Amun and Amunet: secrecy

Collectively known as the Ogdoad, the eight deities built an island in the infinite sea of Nun. It was on this island that the ibis Thoth laid an egg. When it hatched, this egg would become the sun.[15]

Thoth Plays Draughts with the Moon

Even outside of Hermopolis, Thoth played an important role in the creation of the cosmos.

In Heliopolis, the foundation of their religious belief was the Ennead—a group of gods that would ultimately grow to include Ra, Shu, Tefnut, Geb, Nut, Osiris, Set, Isis, and Nephthys. These nine gods were not formed all at once, however, and if not for Thoth’s intervention the list would have been cut short.[16]

Ra created two children, Shu and Tefnut, who in turn bore the deities Geb and Nut. Ra wanted to claim his granddaughter Nut for himself, and grew jealous when he saw Geb and Nut lying together. In a fit of envious rage, he placed a curse on her such that she would not be able to bear children in any month of the year.

Wise Thoth (whose existence at this point was unexplained) had a plan to help Nut get around the curse.[17] He had been playing draughts with the moon, and—as the god of wisdom—had found himself winning more often than not. He proposed a wager: if he won, then the moon would have to give Thoth a portion of her illumination.

An ibis-headed Thoth can be seen on the ceiling at the Temple of Hathor in the Dendera Temple complex. He appears to the right of a waxing and waning moon, which features the Eye of Horus.

TerryJLawrence / iStockThe moon accepted the bet (no one said the moon was good at gambling) and ultimately gave Thoth 1/70th of her illumination. Thoth decided to add his winnings—totalling five additional days of light—to the end of the 360-day Egyptian calendar. Because these final five days (referred to as epagomenal days) existed outside of the standard calendar, Ra’s curse did not apply to them.[18]

Now free from Ra’s curse, Nut was able to gave birth at last.

Thoth and the Eye of the Sun

Ra was prone to anger and jealousy, which often resulted in disagreements with the other gods. In this myth, Ra and his Eye got into an argument. The Eye of Ra was closely associated with the goddess Tefnut, and in this tale the two names were used interchangeably.

The Egyptians regarded eyes as deities unto themselves, likely because irt, the word for eye, sounded like the Egyptian word for “doing” or “acting.” Because irt was feminine, even masculine god’s eyes were regarded as goddesses.

After a particularly nasty argument, Tefnut decided enough was enough and departed for the land of Nubia (or Liberia, depending on the tale). Filled with rage from the argument, she rampaged through the countryside as a fire-breathing lioness.

Depending on the version of the myth, Ra either wished to have her returned so he could use her newfound aggression against his enemies, or he realized he had been relying on her for protection and her absence made him vulnerable. In any case, a desperate Ra sent Thoth to retrieve her.

Thoth tracked her down and, in an effort to get close to her without being recognized, transformed himself into a dog-faced baboon. Despite his disguise, Tefnut identified the god of wisdom for what he was and prepared to attack him.

Thinking on his feet, Thoth quickly told the goddess that “fate punishes every crime.”[19] This gave Tefnut pause, which in turn provided Thoth the opportunity to begin persuading the upset goddess to come back with him.

He told her tales of Egypt’s beauty, as well as animal-based fables extolling the virtues of the strong allying themselves with the weak and the value of peace.

One version of this myth says that Thoth had to ask Tefnut 1,077 times before she finally acquiesced.[20] Eventually, Thoth convinced the volatile goddess to return with him to Egypt. On their journey home, they were met with great fanfare and celebration in each town they passed through. By the time they had reached Memphis, Tefnut’s anger had fully subsided.

This allegorical myth referenced the domesticating effects of civilization, and traced Tefnut’s transformation into a model citizen.[21]

When the pair finally returned to Memphis, Ra hosted a great festival in Tefnut’s honor and congratulated Thoth for his excellent work.[22] In some versions of the myth, Thoth was rewarded with the goddess Nehemtawy as his bride. Nehemtawy’s precise nature remains unclear: she may have been a manifestation of Tefnut, transformed by civilization as she left the desert, or an independent goddess unrelated to preceding events.[23]

Thoth the Advisor

While Thoth had only a few myths directly related to him, he appeared in nearly all major Egyptian myths as an advisor. Most prominently, Ra appointed him his vizier after deciding that handling the daily affairs on earth had become too much for him.[24]

Viziers weren’t just found in Disney movies! These officials served as the chief judges of ancient Egypt and acted as the pharaoh’s representative in their absence.[25]

This relief from the mortuary temple of Rameses II depicts several Egyptian gods, including the ibis-headed Thoth, who appears in the center of the scene.

Steve F-E-CameronCC BY-SA 3.0To facilitate his new responsibilities, Ra gave Thoth the ibis to use as his personal messenger, power over the sun and the moon, and apes that he could use against his enemies.[26] Beyond his role in advising Ra, many myths featured Thoth offering insightful advice that the other gods usually had the wherewithal to take:

During Osiris’s reign, Thoth served as his vizier. When Osiris embarked on his civilizing tour of the region and left Isis in charge, Thoth remained behind to advise her as well.[27]

After Isis gave birth to Horus, Thoth advised her to go into hiding until the boy was old enough to challenge Set.[28]

In one bizarre instance, Set claimed that he had intercourse with Horus, jepoardizing the latter’s claim to the throne. Using his magic, Thoth called forth the semen of both Horus and Set to see who was telling the truth. Unbeknownst to Set, Isis had figured out his ploy. In the dead of night, she had sprinkled Horus’s semen into Set’s lettuce and ensured that Set’s semen had been washed into the Nile. On Thoth’s command, Set’s semen dutifully emerged from the swamps, while Horus’s semen emerged from Set’s ears. The case was thus decided in Horus’s favor. In one final twist, the semen emerging from Set’s ears formed a solar disc that Thoth proceeded to wear as a crown.[29]

Thoth the Healer

Another of Thoth’s recurring roles was that of the divine healer. He was capable of healing almost any ailment—even those the powerful Isis could not manage:

When Geb was just a prince, he became prone to acts of aggression against his father Shu. In one spiteful act, he turned himself into a boar and ate the Eye of Ra (the moon). The Eye sickened Geb terribly, causing blood to pour forth from his skin. While Thoth’s services weren’t necessary to heal Geb, the ibis-headed healer did return the Eye to its rightful place.[30]

Thoth was integral in the resurrection of Osiris. He assisted with the embalming process, and with reassembling Osiris’s dismembered corpse.[31] While he did not perform the spell that resurrected Osiris, he did instruct Isis in the use of charms necessary for the process.[32]

While Isis was on the run from Set, her son Horus fell terribly ill from a scorpion sting. Despite Isis’s medical prowess, she was incapable of healing him. Her woe (or perhaps Horus’s serious injury) brought Ra’s solar barque to a halt, prompting Thoth to visit and figure out what was wrong. Upon discerning the nature of the problem, Thoth recited a lengthy spell (much to Isis’s chagrin) and restored Horus to full health.[33]

During a battle between Horus and Set, Set managed to seize the eye of Horus and threw it “into the darkness beyond the edge of the world.” Thoth witnessed this and upon retrieving the eye found it broken. Thankfully, the god of wisdom was able to repair the eye and return it to Horus.[34]

After a battle where Horus had taken Set captive, Isis felt bad for her imprisoned brother and set him free. Furious at his mother’s betrayal, Horus struck a mighty blow, decapitating her instantly. Thoth replaced her head with Hathor’s horns and solar disk, thus allowing the goddess to live again.[35]

Thoth, and the Weighing of the Heart Ceremony

For the average Egyptian, one of Thoth’s most important roles was the one he would play after they died. The Egyptian afterlife was not guaranteed, and required one to live righteously to gain entry. Thoth would assess a person’s worthiness by weighing their heart against a feather of maat.

If you had lived righteously, the scales would balance and allow entry into the afterlife. If the scales did not balance, however, the unfortunate soul would be devoured by the chimeric beast Ammit and cease to exist.

This Thoth-inspired amulet (c. 320-250 BCE) was believed to protect the dead during the weighing of the heart ceremony.

The Walters Art Museum CC0Curiously, the Egyptians believed that the process could be cheated. Those buried with the correct amulets and spells could prevent theirs hearts from revealing the sins they had committed in life. This belief offered some explanation for the elaborate burial rituals of the Egyptian elite: those who had the resources to guarantee entry into the afterlife, used them

Thoth and Ritual Animal Sacrifice

The ancient Egyptians are best remembered for their massive burial structures, hidden tombs, and mummifications. While lesser known, animal sacrifice was also a significant part of their religion.

Animal sacrifice was not uniformly popular throughout Egyptian history, and seems to have increased during times of political strife. The practice peaked during the Third Intermediate period following the collapse of the New Kingdom (c. 1075 BCE).

Though this period saw a rapid succession of rulers, life for the common person went on with little disruption. In fact, most people may have had more disposable income due to the reduction in taxes being sent to a central government authority.[37]

The pharaoh was more than just a political ruler, however—he was also the center of the ancient Egyptian religion. With no consistent religious leadership, personal piety gained significance. Wealthy Egyptians could afford to give bronze offerings, while less well-off worshippers offered embalmed animal sacrifices.

A CT scan of this elaborate mummy (30 BCE –100 CE) has revealed that there are nothing but feathers inside.

Brooklyn MuseumCC BY 3.0Across Egypt, there were at least 31 animal necropolises containing at least 20 million embalmed animals. An estimated six million of these animals were ibises.[38] Thoth could take the form of an ibis, and the birds also served as his personal messengers. It is believed, then, that these sacrifices were dedicated to the ibis-headed deity.[39]

Though some of the sacrificed birds were wrapped with written petitions, most were not. This suggests that prayers or requests may have been spoken to the creatures before they were sacrificed.

It is not entirely clear what the majority of these petitions were about. As the god of wisdom, science, medicine, and judgement, however, Thoth would have been able to offer a wide range of blessings.

While some scholars believe that sacrifice on this scale required industrial farming practices, more recent evidence has suggested these birds were actually wild fowl captured solely for sacrifice.[40] In either case, the Egyptian fervor for sacrifice was a hugely lucrative business.

Unscrupulous priests and vendors would at times sell fake mummies, often containing just a shard of bone from the alleged animal. Records from the Temple of Thoth at Saqqara included corruption charges laid against the priesthood in relation to counterfeit mummies. Such records, often written on ostraca (potsherds), indicated that six priests were imprisoned for their crimes and reforms were implemented to prevent future fraud.[41]

Pop Culture

While many deities faded into obscurity following Egyptian decline, Thoth remained popular across a number of cultures, and has even made appearances in modern works.

In Greece Thoth became Hermes, or Hermes Trismegistus (Hermes the Thrice-Great), but also lived on in philosophy as Thoth, the ancient Egyptian god of wisdom. In Plato’s Phaedrus, Socrates cited Thoth while defending the importance of writing.[42]

Aleister Crowley’s famous tarot card reading companion book was entitled The Book of Thoth. Released in 1944, the book explained Egyptian Tarot card reading, as well as the underlying philosophy of the practice.[43]

The first month of the Coptic Calendar, Thout, was named after Thoth. The month begins September 11th and ends October 10th.

In Neil Gaiman’s novel American Gods, Thoth appeared as a character named Mr. Ibis. In this guise, Thoth worked with Jacquel (Anubis) as a funeral director, a nod to his role as the judge of the dead.[44]