In Wikidata, Wikipedia’s sister project for storing statements of fact as linked, open data, we record a number of unique identifiers.

For example, Tim Berners-Lee has the VIAF identifier “85312226” and is known to the Internet Movie Database as “nm3805083”.

We know that we can convert these to URLs by adding a prefix, so

by adding the prefixes:

- https://viaf.org/viaf/

- http://www.imdb.com/Name?

respectively. We only need to store those prefixes in Wikidata once each.

The Houses of Parliament in August 2014,

picture by Henry Kellner, CC BY-SA 3.0

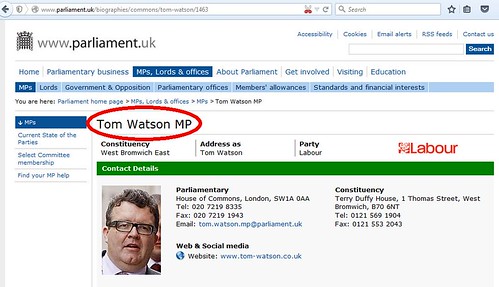

The United Kingdom Parliament website also uses identifiers for MPs and members of the House of Lords.

For example, Tom Watson, an MP, is “1463”, and Jim Knight, aka The Lord Knight of Weymouth, is “4160”.

However, the respective URLs are:

meaning that the prefixes are not consistent, and require you to know the name or exact title.

Yet more ridiculous is that, if Tom Watson ever gets appointed to the House of Lords, even though his unique ID won’t change, the URL required to find his biography on the parliamentary website will change — and, because we don’t know whether he would be, say Lord Watson of Sandwell Valley, or Lord Watson of West Bromwich, we can’t predict what it will be.

When building databases, like Wikidata, this is all extremely unhelpful.

What we would like the parliamentary authorities to do — and what would benefit others wanting to make use of parliamentary URLs — is to use a standard, predictable type of URL, for example http://www.parliament.uk/biographies/1463 which uses the unique identifier, but does not require the individual’s house, name or title, and does not change if they shift to “the other place”.

If necessary they could then make that redirect to the longer URLs they prefer (though I wouldn’t recommend it).

I’ve asked them; but they don’t currently do this. In fact they explained their preference for the longer URLs thus:

…we are unable [sic] to shorten the url any further as the purpose of the current pattern of the web address is to display a pathway to the page.

The url also identifies the page i.e the indication of biographies including the name of the respective Member as to make it informative for online users who may view the page.

I find these arguments unconvincing, to say the least.

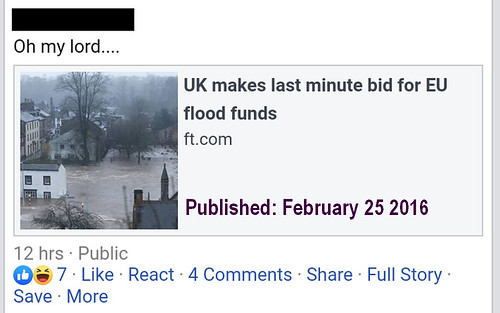

There’s a big enough clue on the page, without needing to read the URL to identify its subject

Furthermore, the most verbose parts of the URLs are non-functioning; if we truncate Tom’s URL by simply dropping the final digit: http://www.parliament.uk/biographies/commons/tom-watson/146, then we get the biography of a different MP. On the other hand, if we change it to, say: http://www.parliament.uk/biographies/commons/t/1463, we still get Tom’s page. Try them for yourself.

So, how can we help the people running the Parliamentary website to change their minds, and to use a more helpful URL structure? Who do we need to persuade?

Like this:

Like Loading...