Abstract

S3I-201 (NSC 74859) is a chemical probe inhibitor of Stat3 activity, which was identified from the National Cancer Institute chemical libraries by using structure-based virtual screening with a computer model of the Stat3 SH2 domain bound to its Stat3 phosphotyrosine peptide derived from the x-ray crystal structure of the Stat3β homodimer. S3I-201 inhibits Stat3·Stat3 complex formation and Stat3 DNA-binding and transcriptional activities. Furthermore, S3I-201 inhibits growth and induces apoptosis preferentially in tumor cells that contain persistently activated Stat3. Constitutively dimerized and active Stat3C and Stat3 SH2 domain rescue tumor cells from S3I-201-induced apoptosis. Finally, S3I-201 inhibits the expression of the Stat3-regulated genes encoding cyclin D1, Bcl-xL, and survivin and inhibits the growth of human breast tumors in vivo. These findings strongly suggest that the antitumor activity of S3I-201 is mediated in part through inhibition of aberrant Stat3 activation and provide the proof-of-concept for the potential clinical use of Stat3 inhibitors such as S3I-201 in tumors harboring aberrant Stat3.

Proteins of the STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription) family are activated in response to cytokines and growth factors and promote proliferation, survival, and other biological processes (1–3). STATs are activated by phosphorylation of a critical tyrosine residue, which is mediated by growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases, Janus kinases, or the Src family kinases. Upon tyrosine phosphorylation, dimers of STATs formed between two phosphorylated monomers translocate to the nucleus, bind to specific DNA-response elements in the promoters of _target genes, and induce gene expression. Aberrant activity of one of the family members, Stat3, contributes to carcinogenesis and tumor progression by up-regulating gene expression and promoting dysregulated growth, survival, and angiogenesis and modulating immune responses (2–9).

As a critical step in STAT activation (10), the dimerization between two STAT monomers presents an attractive _target to abolish Stat3 DNA-binding and transcriptional activity and to inhibit Stat3 biological functions (11, 12). Stat3 dimerization relies on the reciprocal binding of the SH2 domain of one monomer to the Pro-pTyr-Leu-Lys-Thr-Lys sequence of the other Stat3 monomer. To pursue the development of inhibitors of Stat3 signaling, key structural information gleaned from the x-ray crystal structure of the Stat3β homodimer (13) was used in the computational modeling and automated docking of small molecules into the SH2 domain of a Stat3 monomer, relative to the bound native pTyr peptide, to identify binders of the Stat3 SH2 domain, and potentially disruptors of Stat3·Stat3 dimers (14, 15).

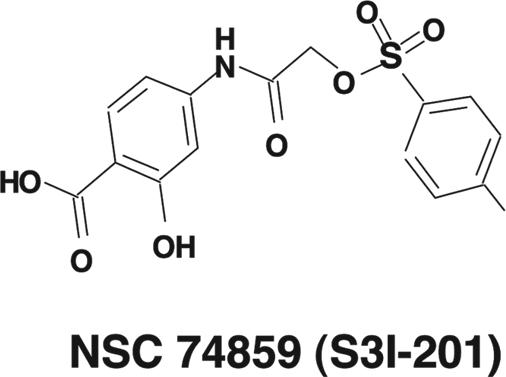

Structure-based high-throughput virtual screening of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) chemical libraries identified the high-scoring compound NSC 74859 (resynthesized as a pure sample and named S3I-201), which selectively inhibits Stat3 DNA-binding activity in vitro with an IC50 value of 86 ± 33 μM. Furthermore, S3I-201 induces growth inhibition and apoptosis of malignant cells in part by constitutively inhibiting active Stat3 and induces human breast tumor regression in xenograft models.

Results

Computational Modeling and Virtual Screening.

Our computational modeling and virtual screening study used the GLIDE (Grid-based Ligand Docking from Energetics) software (16, 17) (available from Schrödinger, Portland, OR) for the docking simulations and relied on the x-ray crystal structure of the Stat3β homodimer bound to DNA (13) determined at 2.25-Å resolution (1BG1 in the Protein Data Bank). For the virtual screening, DNA was removed and only one of the two monomers was used (see Fig. 1). To validate the docking approach, the native pTyr (pY) peptide, APpYLKT, was extracted from the crystal structure of one of the monomers and docked to the other monomer, whereby GLIDE produced a docking mode that closely resembled the x-ray crystal structure (data not shown). Three-dimensional structures of compounds from the NCI's chemical libraries were downloaded from the NCI Developmental Therapeutics Program web site (http://dtp.nci.nih.gov/docs/3d_1020;database/Structural_1020;information/structural_1020;data.html) and processed with LigPrep software (available from Schrödinger) to produce 2,392 3D structures for the Diversity Set and 150,829 3D structures for the Plated Set. Then GLIDE 2.7 SP (Standard Precision mode) docked each chemical structure (for small molecule) into the pTyr peptide-binding site within the SH2 domain of the monomer to obtain the best docking mode and docking score.

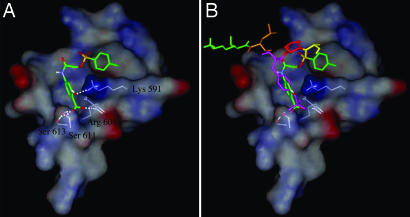

Fig. 1.

Application of computational modeling in in silico screening (virtual screening) to identify the compound S3I-201 from a chemical database. (A) S3I-201 (NSC 74859) docked to the SH2 domain of Stat3; a solvent-accessible surface of the protein (rendered on a 6-Å shell of residues surrounding the ligand) is shown. It is color coded according to the electrostatic potential, with red most negative and dark blue most positive. Hydrogen bonding to Lys-591, Ser-611, Ser-613, and Arg-609 is shown by white dashed lines. Carbon atoms of S3I-201 are shown in green. (B) S3I-201 docked to the SH2 domain of Stat3 along with pTyr peptide. Coloring for pTyr peptide is as follows: Ala, yellow; Pro, red; pTyr, magenta; Leu, orange; and Lys, green.

The best score observed from the docking studies was −11.7 kcal/mol, relative to the native phosphopeptide sequence APpYLK (scored as −11.9 kcal/mol). Typically, compounds receiving highly favorable scores (more negative values) have structural features that include sulfonyl, carboxyl, and hydroxyl functional groups. The current hit, S3I-201 (NSC 74859), contains all three groups.

Identification of a Chemical Probe as Inhibitor of Stat3 DNA-Binding Activity.

The best-scoring compounds were selected for experimental analysis using an in vitro Stat3 DNA-binding assay and EMSA analysis. See supporting information (SI) Results for more details. Results for the confirmed hit, S3I-201, show differential inhibition of DNA-binding activities of STATs. Fig. 2A Left shows potent inhibition of Stat3 DNA-binding activity by S3I-201, with an average IC50 value of 86 ± 33 μM. For selectivity against STAT family members, nuclear extract preparations from EGF-stimulated mouse fibroblasts overexpressing the human epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) NIH 3T3/hEGFR, containing activated Stat1, Stat3, and Stat5, were preincubated with or without S3I-201 before incubation with the radiolabeled probes, as described in Materials and Methods. EMSA analysis of the DNA-binding activities shows Stat3·Stat3 (upper), Stat1·Stat3 (intermediate) and Stat1·Stat1 (lower) bands of complexes with the hSIE probe (Fig. 2A Right Upper) and Stat5·Stat5 (upper) and Stat1·Stat1 (lower) bands of complexes with the MGFe probe (Fig. 2A Right Lower). S3I-201 preferentially inhibits Stat3 DNA-binding activity over that of Stat1 (IC50 values, Stat3·Stat3, 86 ± 33 μM; Stat1·Stat3, 160 ± 43 μM; and Stat1·Stat1, >300 μM) and inhibits that of Stat5 with ½ the potency (IC50 value, 166 ± 17 μM). The appearance of different degrees of activity of S3I-201 at 300 μM is due to the fact that different nuclear extract preparations were used, one from the v-Src-transformed mouse fibroblasts (NIH 3T3/v-Src) containing only activated Stat3 (Fig. 2A Left) and the other from the EGF-stimulated NIH 3T3/hEGFR that contains activated Stat1, Stat3, and Stat5 (Fig. 2A Right). Supershift analysis with anti-Stat3 antibody shows protein·hSIE complex (Fig. 2A Left, the last two lanes) contains Stat3, whereas use of anti-Stat1 antibody or anti-Stat5 antibody confirms that protein·MGFe complexes contain Stat1 or Stat5, respectively (Fig. 2A Right, the last two lanes).

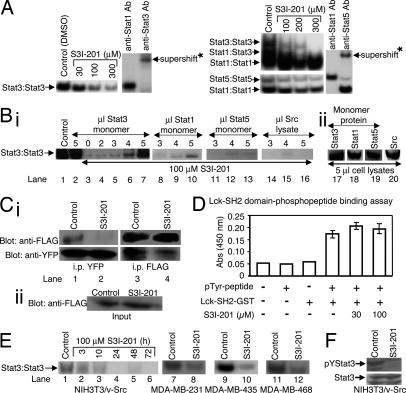

Fig. 2.

Evaluation for effects of S3I-201 on STATs, Shc, Src, and Erks activation, and on Lck-SH2 domain phosphopeptide binding. (A) Nuclear extracts containing activated STAT proteins were preincubated with or without S3I-201 for 30 min at room temperature before incubation with radiolabeled hSIE probe, which binds Stat1 and Stat3, or MGFe probe, which binds Stat1 and Stat5, or nuclear extracts were incubated with anti-Stat1, anti-Stat3, or anti-Stat5A antibody for 30 min at room temperature before incubation with radiolabeled probes, and were subjected to EMSA analysis. (B) (i) Cell lysates containing activated Stat3 were preincubated with S3I-201 or without (control, 0.05% DMSO) in the presence or absence of increasing amount of cell lysates containing inactive Stat3 protein (monomer), inactive Stat1 protein (monomer), inactive Stat5 protein (monomer), or Src protein before incubation with radiolabeled hSIE probe followed by EMSA analysis. (ii) SDS/PAGE and Western blot analysis of cell lysate preparations of equal amounts of total protein containing inactive Stat3 (monomer), Stat1 (monomer), or Stat5 (monomer), or Src protein and probed with anti-Stat3, anti-Stat1, anti-Stat5, or anti-Src antibody. (C) (i) SDS/PAGE and Western blot analysis of Stat3-yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) immunoprecipitates (i.p. YFP, Left) probing for FLAG-Stat3 (anti-FLAG, Upper) or Stat3-YFP (anti-YFP, Lower), or of FLAG-Stat3 immunoprecipitates (i.p. FLAG, Right) probing for Stat3-YFP (anti-YFP, Lower) or FLAG-Stat3 (anti-FLAG, Upper); (ii) SDS/PAGE and Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates from FLAG-ST3-transiently transfected cells (input) treated with S3I-201 or untreated (control) probing for FLAG. (D) In vitro ELISA for the binding of Lck-SH2-GST to the conjugate biotinylated pTyr-peptide (EPQpYEEIEL), and effects of increasing concentration of S3I-201. Values are the mean ± SD of three independent determinations. (E) EMSA analysis of Stat3 DNA-binding activity in nuclear extract preparations from v-Src-transformed mouse fibroblasts (NIH 3T3/v-Src) treated for the indicated times or from the human breast cancer MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-435, and MDA-MB-468 cells treated for 48 h with 100 μM S3I-201 and incubated with radiolabeled hSIE probe. (F) SDS/PAGE and Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates from NIH 3T3/v-Src fibroblasts untreated (control) or treated with S3I-201 (100 μM, 24 h) probing with anti-pTyr-705-Stat3 or anti-Stat3 antibody. Positions of STAT·DNA complexes or proteins in gel are labeled; control lanes represent nuclear extracts treated with 0.05% DMSO, and nuclear extracts or cell lysates prepared from 0.05% DMSO-treated cells; asterisks (∗) indicate supershifted complexes of STAT·probe·antibody in the presence of anti-Stat1, anti-Stat3, or anti-Stat5 antibody.

S3I-201 Disrupts Stat3·Stat3 Complex Formation in Vitro and in Intact Cells.

To provide experimental data in support of S3I-201's binding to Stat3, we asked whether unphosphorylated, inactive Stat3 monomer could interfere with the inhibitory effect of S3I-201 on active Stat3 DNA-binding (inactive Stat3 monomer will interfere with the inhibitory activity of S3I-201 if it interacts with the compound). To answer this question, cell lysates of unphosphorylated, inactive Stat3 monomer protein prepared from Sf-9 insect cells infected with only baculovirus containing Stat3, as previously described (11, 12, 18, 19), and cell lysates of activated Stat3 dimer protein were mixed together; the mixture was preincubated with S3I-201 for 30 min before incubation with the radiolabeled hSIE probe and EMSA analysis carried out in the same manner as for Fig. 2A. The unphosphorylated, inactive Stat3 monomer by itself had no significant effect on DNA-binding activity of activated Stat3 (Fig. 2B, compare lane 2 to lane 1), because inactive Stat3 monomer is incapable of binding DNA (19). By contrast, the presence of inactive Stat3 monomer diminished the inhibitory effect of S3I-201 on the activated Stat3 in a dose-dependent manner, resulting in the recovery of the active Stat3 DNA-binding activity (Fig. 2B, lanes 5–7 versus lanes 3 and 4). The Stat3 DNA-binding activity that was otherwise inhibited (Fig. 2B, lanes 3 and 4) was partially or completely restored in the presence of 4 or 5 μl of inactive Stat3 lysates, respectively (Fig. 2B, lanes 6 and 7). These findings support the S3I-201–Stat3 interaction and suggest the interaction is independent of the activation status of Stat3. Similar studies were performed by using independently prepared cell lysates from Sf-9 insect cells infected with only the baculovirus containing Stat1, Stat5, or Src, as we have previously reported (11, 12, 18, 19). In contrast to the effect observed with the inactive Stat3 monomer (Fig. 2B, lanes 5–7), EMSA analysis showed that the presence of inactive Stat1, Stat5, or Src lysate induces no significant recovery of Stat3 DNA-binding activity (Fig. 2B, lanes 8–10, 11–13, and 14–16, respectively). In the case of the Stat1 monomer lysate, minimal recovery of Stat3 DNA-binding activity is observed (Fig. 2B, lane 10), which is evidence of a weak interaction of the Stat1 protein with S3I-201, as revealed in the initial evaluation (Fig. 2A Right). The amounts of proteins for each of Stat1, Stat3, or Stat5 monomer or the Src lysate used in these studies was determined by SDS/PAGE and Western blot analysis to be similar (Fig. 2B, lanes 17–20).

To further confirm the interaction of S3I-201 with Stat3 and to demonstrate that it blocks Stat3·Stat3 dimerization in intact cells, Stat3 pull-down assays were performed. Viral Src transformed (NIH 3T3/v-Src) mouse fibroblasts stably expressing Stat3-YFP were transiently transfected with Flag-Stat3 (FLAG-ST3), treated either with 0.05% DMSO (control) or with S31–201 for 24 h, and then subjected to pull-down assay and SDS/PAGE. Western blot analysis for FLAG of whole-cell lysates shows equal expression of the FLAG-ST3 protein in the lysates in the transiently transfected cells in both the control and S3I-201-treated cells (Fig. 2Cii). Western blot analysis probing with anti-FLAG antibody of the Stat3-YFP immunoprecipitates from control cells showed the presence of FLAG-ST3 protein (Fig. 2Ci Upper Left, lane 1), suggesting Stat3-YFP and FLAG-ST3 proteins were pulled down together as a complex. By contrast, Western blot analysis probing with anti-FLAG antibody showed no detectable level of FLAG-ST3 protein in the Stat3-YFP immunoprecipitates from S3I-201-treated cells (Fig. 2Ci Upper Left, lane 2 vs. 1), suggesting the disruption by S3I-201 of the complex formation between Stat3-YFP and FLAG-ST3 proteins. The amounts of Stat3-YFP in the immunoprecipitates are shown in Fig. 2Ci Lower Left. Similarly, Western blot analysis probing with anti-YFP antibody of the FLAG-ST3 immunoprecipitates from control cells showed Stat3-YFP present in the pulled-down lysate (Fig. 2Ci Lower Right, lane 3), but significantly reduced in the FLAG-ST3 immunoprecipitates from the S3I-201-treated cells (Fig. 2Ci Lower Right, lane 4 vs. 3). The FLAG-ST3 protein amounts in the immunoprecipitates are shown (Fig. 2Ci Upper Right).

S3I-201 Does Not Interfere with Lck-SH2 Domain–Phosphotyrosine Interaction.

To further investigate the selectivity of S3I-201 and to rule out the possibility that it interacts with other SH2 domain-containing proteins, we evaluated its effect on the binding between the unrelated Src family protein, Lck, and the cognate phosphopeptide, EPQpYEEIEL. We used the in vitro ELISA study involving the Lck-SH2-GST protein and the conjugate pTyr peptide, biotinyl-ε-Ac-EPQpYEEIEL-OH (20), as described in Materials and Methods. Results from the ELISA show that the copresence of the Lck-SH2-GST protein and its cognate pTyr peptide results in signal induction (Fig. 2D, bar 4), suggesting an interaction between the two (20). The addition of 30 μM and 100 μM S3I-201 has no effect on the signal induction (Fig. 2D, compare bars 5 and 6 to bar 4), indicating that S3I-201 does not interfere with the binding of the Lck SH2 domain to its cognate pTyr peptide.

S3I-201 Inhibits Stat3 Activation in Intact Cells.

To determine effect of S3I-201 on intracellular Stat3 activation, NIH 3T3/v-Src mouse fibroblasts and human breast cancer MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-435, and MDA-MB-468 cells, which harbor constitutively active Stat3 (21–23), were treated with the compound and nuclear extracts were prepared for Stat3 DNA-binding activity in vitro and EMSA analysis. Compared with control (0.05% DMSO-treated cells, lane 1), S3I-201 induced a time-dependent inhibition of constitutive Stat3 activation in NIH 3T3/v-Src fibroblasts (Fig. 2E, lanes 4–6). By 24 h, constitutive Stat3 activation was significantly inhibited in all three cell lines (Fig. 2E, lanes 4–6 and 8, 10, and 12). Furthermore, SDS/PAGE and Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates from NIH 3T3/v-Src fibroblasts show pTyr-705 Stat3 levels were significantly diminished after 24-h treatment with S3I-201 (Fig. 2F), whereas the total Stat3 protein level remained unchanged. This inhibition of tyrosine phosphorylation may be explained by the fact that, by binding to the Stat3 SH2 domain, S3I-201 prevents Stat3 from binding to the pTyr motifs of the receptor tyrosine kinases and subsequently blocks de novo phosphorylation by tyrosine kinases. By contrast, SDS/PAGE and Western blot analysis performed on whole-cell lysates from mouse fibroblasts transformed by v-Src (NIH 3T3/v-Src) or overexpressing the human EGFR (NIH 3T3/hEGFR) and stimulated by EGF revealed that treatment with S3I-201 for 24 h had no significant effect on the phosphorylation of Shc (pShc), Erk1/2 (pErk1/2), or Src (pSrc) in cells (SI Fig. 7). Total Erk1/2 protein levels were unchanged. Moreover, SDS/PAGE and Western blot analysis with the anti-pTyr antibody 4G10 showed no significant changes in the pTyr profile of NIH 3T3/v-Src fibroblasts after 24-h treatment with S3I-201 (SI Fig. 7).

Selective Inhibition of Stat3 Transcriptional Activity by S3I-201.

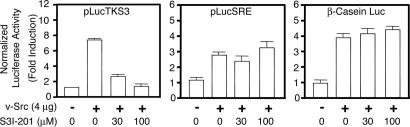

We investigated S3I-201's effect on Stat3-dependent transcriptional activity. Normal mouse fibroblasts (NIH 3T3) were transiently cotransfected with the Stat3-dependent luciferase reporter pLucTKS3 and a plasmid encoding the v-Src oncoprotein that activates Stat3, and cells were untreated (0.05% DMSO, control) or treated with S3I-201. As previously reported (23), v-Src protein mediated induction of the Stat3-dependent luciferase reporter pLucTKS3 activity by ≈7-fold (Fig. 3Left). This Stat3-dependent pLucTKS3 induction was significantly inhibited by the treatment of cells with S3I-201 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3 Left). To examine specificity of effects, normal mouse fibroblasts were cotransfected with the Stat3-independent luciferase reporters pLucSRE (23) or β-casein promoter-driven Luc (24) together with v-Src plasmid and treated with S3I-201 or without (0.05% DMSO). In contrast to the effect on the induction of pLucTKS3 luciferase reporter, v-Src-mediated induction of Stat3-independent pLucSRE (23) or the β-casein promoter-driven Luc (24) was not affected by treatment with S3I-201 (Fig. 3 Center and Right).

Fig. 3.

S3I-201 suppresses Stat3-dependent but not Stat3-independent transcriptional activity. Shown are luciferase reporter activities in cytosolic extracts prepared from normal mouse fibroblasts (NIH 3T3) transiently cotransfected with the Stat3-dependent (pLucTKS3), or the Stat3-independent (pLucSRE or β-casein promoter-driven Luc) luciferase reporters together with a plasmid expressing the v-Src oncoprotein that activates all three reporters, and untreated (0.05% DMSO, control) or treated with 100 μM S3I-201 for 24 h. Values are the mean + SD of three independent determinations.

S3I-201 Blocks Anchorage-Dependent and Independent Growth only in Cells Where Stat3 is Persistently Activated.

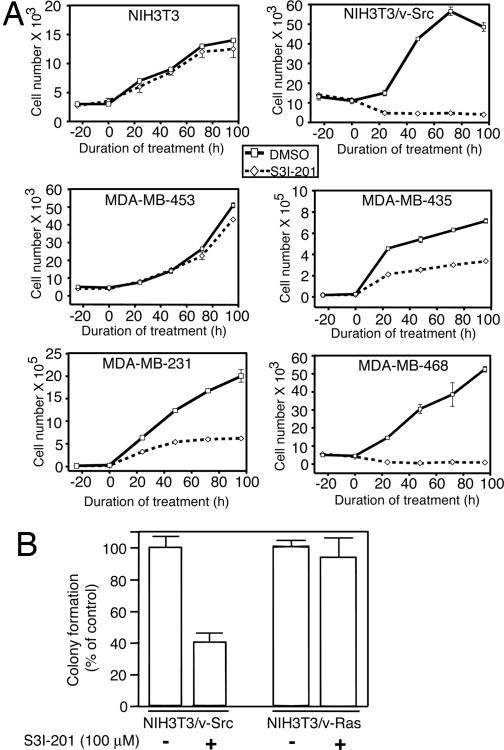

We next determined whether this Stat3 activity inhibitor is able to inhibit the anchorage-dependent and -independent (transformation) growth of human and mouse cancer cell lines. The human breast carcinoma (MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-435, and MDA-MB-468) cell lines and the v-Src-transformed mouse fibroblasts (NIH 3T3/v-Src), which harbor constitutively active Stat3 and the human breast carcinoma MDA-MB-453 cell line and normal mouse fibroblasts (NIH 3T3), which do not harbor aberrant Stat3 activity, were treated with S3I-201 and analyzed for viable cell number by trypan blue exclusion and microscopy (Fig. 4A). S3I-201 significantly reduced viable cell numbers and inhibited growth of transformed mouse fibroblasts NIH 3T3/v-Src and breast carcinoma cell lines (MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-435, and MDA-MB-468) (Fig. 4A). By contrast, growth and viability of normal mouse fibroblasts (NIH 3T3) and the breast carcinoma cell line (MDA-MB-453) without aberrant Stat3 activity were not significantly altered (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, growth of v-Src-transformed mouse fibroblasts in soft-agar suspension is significantly inhibited by S3I-201 (Fig. 4B). By contrast, soft-agar growth of the v-Ras-transformed counterpart (NIH 3T3/v-Ras), which is independent of constitutively active Stat3, is unaffected by treatment with S3I-201 (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

S3I-201 inhibits anchorage-dependent and -independent growth only of cells that contain persistently active Stat3. (A) Normal mouse fibroblasts (NIH 3T3) and v-Src transformed counterparts (NIH 3T3/v-Src), as well as the human breast carcinoma cells (MDA-MB-453, MDA-MB-435, MDA-MB-231, or MDA-MB-468) were untreated (0.05% DMSO, control) or treated with 100 μM S3I-201 and counted by trypan blue exclusion on each of 4 days for viable cell number. Values are the mean ± SD of three independent determinations. (B) v-Src-transformed mouse fibroblasts (NIH 3T3/v-Src) and their v-Ras-transformed counterparts (NIH 3T3/v-Ras) were grown in soft-agar suspension and untreated (0.05% DMSO, control) or treated with 100 μM S3I-201 every 3 days until large colonies were visible, which were enumerated. Values are the mean + SD of three or four independent determinations.

S3I-201 Preferentially Induces Apoptosis of Malignant Cells Harboring Constitutively Active Stat3.

To determine whether the S3I-201 induced loss of tumor cell viability was due to apoptosis, the human breast carcinoma cell lines MDA-MB-453 and MDA-MB-435 and the normal mouse fibroblasts (NIH 3T3) and their v-Src-transformed counterpart (NIH 3T3/v-Src) were untreated (0.05% DMSO, control) or treated with S3I-201 for 48 h and analyzed by annexin V binding and flow cytometry. At 30–100 μM, S3I-201-induced significant apoptosis in the representative human breast carcinoma cell line MDA-MB-435 and NIH 3T3/v-Src, both of which harbor constitutively active Stat3 (Fig. 5A). The breast carcinoma MDA-MB-435 cell line is more sensitive to 30 μM S3I-201 (Fig. 5A). By contrast, the human breast cancer MDA-MB-453 cells and the normal mouse fibroblasts (NIH 3T3), which do not contain abnormal Stat3 activity, are less sensitive to S3I-201 at 100 μM or less (Fig. 5A). At 300 μM or higher, S3I-201 induced general, nonspecific cytotoxicity independent of Stat3 activation status.

Fig. 5.

S3I-201 inhibits cyclin D1, Bcl-xL, and survivin expression and induces apoptosis in a Stat3-dependent manner. (A) Normal NIH 3T3 mouse fibroblasts and their v-Src-transformed counterparts (NIH 3T3/v-Src) and the human breast carcinoma MDA-MB-453 and MDA-MB-435 cell lines were untreated (0.05% DMSO) or treated with 30–300 μM S3I-201 for 48 h and subjected to annexin V staining and flow cytometry. 7AAD, 7-aminoactinomycin D. (B) Human breast carcinoma MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with pcDNA3 (Mock) or Stat3C or were untransfected (Non) (Left), or the v-Src-transformed mouse fibroblasts (NIH 3T3/v-Src) were transfected with pcDNA3 (Mock), the N terminus of Stat3 (ST3-NT), or the Stat3 SH2 domain (ST3-SH2) for 4 h (Right). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were untreated [0.05% DMSO (−)] or treated (+) with 100 μM S3I-201 for an additional 24 h and subjected to annexin V staining and flow cytometry. For A and B, values are the mean + SD of six independent determinations. (C) SDS/PAGE and Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates prepared from the v-Src-transformed mouse fibroblasts (NIH 3T3/v-Src) or the human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells untreated (DMSO, control) or treated with 100 μM S3I-201 for 48 h. Probing was with anti-cyclin D1, anti-Bcl-xL, and anti-survivin antibodies. Western blot data are representative of three independent analyses.

We reasoned that if the ability of S3I-201 to induce tumor cell apoptosis is due to its ability to inhibit Stat3 activation, then the constitutively dimerized and persistently activated Stat3C (25) should rescue cells from S3I-201-induced apoptosis. To this end, the breast carcinoma MDA-MB-231 cells, which harbor activated Stat3, were transiently transfected with Stat3C and evaluated for apoptosis. Consistent with results in Fig. 5A, S3I-201 induced 50–80% apoptosis in untransfected or mock-transfected human breast carcinoma MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 5B Left). By contrast, cells transfected with Stat3C and treated with S3I-201 showed greatly diminished apoptosis (Fig. 5B Left), <2-fold compared with 9- or 5-fold apoptosis in nontransfected or mock-transfected cells, respectively. There is an increase in the background level of cell death, which could be due to the effects of transfection.

To establish that the effect of S3I-201 is due to its interaction with the Stat3 SH2 domain, similar studies were performed in cells that were transiently transfected with an expression vector for either the N-terminal region of Stat3 (ST3-NT) or the Stat3 SH2 domain (ST3-SH2) and treated with or without S3I-201. Annexin V binding and flow cytometry showed that although mock-transfected cells were strongly induced by S3I-201 to undergo apoptosis (Fig. 5B Right), similar to the Stat3C-transfected cells, the overexpression of the Stat3-SH2 domain diminished the apoptotic effects of S3I-201 (Fig. 5B Right). In contrast, ST3-NT has no effect on the ability of S3I-201 to induce apoptosis of malignant cells (Fig. 5B Right).

S3I-201 Represses the Expression of the Stat3-Regulated Genes Encoding Cyclin D1, Bcl-xL, and Survivin.

To investigate the molecular mechanisms for the cell growth inhibition and apoptosis by S3I-201, we examined the expression of the known Stat3 _target genes in the v-Src-transformed mouse fibroblasts (NIH 3T3/v-Src) and the human breast carcinoma MDA-MB-231 cell line, which harbor constitutively active Stat3. Immunoblot analysis of whole-cell lysates showed significant reduction in expression of the cyclin D1, Bcl-xL, and survivin proteins in response to S3I-201 treatment (Fig. 5C), indicating that S3I-201 represses induction of the cell cycle and anti-apoptotic regulatory genes in malignant cells.

S3I-201 Induces Regression of Human Breast Tumor Xenografts.

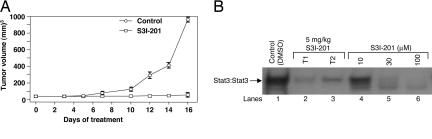

We extended these studies to evaluate the antitumor efficacy of S3I-201 in mouse models with human breast tumor xenografts that harbor constitutively active Stat3. Human breast (MDA-MB-231) tumor-bearing mice were given an i.v. injection of S3I-201 or vehicle every 2 or every 3 days for 2 weeks, and tumor measurements were taken every 2–3 days. Compared with control (vehicle-treated) tumors, which continued to grow, human breast tumors in mice that received S3I-201 displayed strong growth inhibition (Fig. 6A). Continued evaluation of treated mice on termination of treatment showed no resumption of tumor growth (data not shown), suggesting potentially a long-lasting effect of S3I-201 on tumor growth. To determine that _target was inhibited by S3I-201, lysates were prepared from tumor tissue from one control animal and from the residual tumor tissue in two treated-mice for Stat3 DNA-binding activity in vitro, as we have previously done (18). EMSA analysis showed strong inhibition of Stat3 DNA-binding activity in residual tumor tissue from mice treated with S3I-201 (T1 and T2) compared with control tumor (Fig. 6B, lanes 1–3). See SI Results for SDS/PAGE and Western blot analysis of lysates. Moreover, EMSA analysis of in vitro Stat3 DNA-binding activity also showed that preincubation of lysates of equal total protein from control tumor tissue with 10, 30, and 100 μM S3I-201 before incubation with radiolabeled hSIE probe resulted in a dose-dependent abrogation of Stat3 activity (Fig. 6B, lanes 4–6), as observed originally in Fig. 2A Left. Together these studies establish the proof-of-concept for the antitumor effect of S3I-201 in tumors that harbor constitutively active Stat3.

Fig. 6.

Tumor growth inhibition by S3I-201. (A) Human breast (MDA-MB-231) tumor-bearing mice were given S3I-201 (5 mg/kg) i.v. every 2 or every 3 days. Tumor sizes were monitored every 2–3 days, converted to tumor volumes, and plotted. Values are the mean ± SD of eight tumor-bearing mice each. (B) Three days after the last S3I-201 injection, animals were killed, tumors from one control animal (DMSO-treated) or residual tumor tissue from two S3I-201-treated (T1 and T2) mice were extracted, and lysate preparations with equal total proteins were analyzed for Stat3 activation by incubating with radiolabeled hSIE probe and subjecting the products to EMSA analysis (lanes 1–3), or lysates from control tumor tissue of equal total proteins were preincubated with or without increasing concentrations of S3I-201 before incubation with radiolabeled hSIE probe and subjecting the products to EMSA analysis (lanes 1, 4, 5, and 6). Positions of Stat3·DNA complexes are shown.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates the feasibility of using x-ray crystallographic data and computational modeling as a basis for a structure-based virtual screening to identify chemical probes and small-molecule binders of the Stat3 SH2 domain. Similar computational analysis has been applied in the development of inhibitors of Stat3 and other proteins (14, 15). The docking pose of S3I-201 suggests that its aminosalicylic moiety mimics the phenylphosphate group of the PpYLKT motif. Furthermore, its carboxyl group is hydrogen bonded to Arg-609, Ser-611, and Ser-613 of Stat3, while the phenolic hydroxyl group is hydrogen-bonded to Lys-591. Moreover, the proximity of the Lys-591 to the benzene ring with the phenolic hydroxyl group suggests the possibility of a stabilizing π-electron–cation interaction. Also, the tolyl group is buried within a partially hydrophobic pocket, which contains the tetramethylene portion of the side chain of Lys-592 and the trimethylene portion of the side chain of Arg-595, along with residues Ile-597 and Ile-634. We believe that these features (the phosphate mimic and hydrophobic side chain) combine and explain how S3I-201 binds to the SH2 domain of Stat3.

The native pTyr peptide inhibitor of Stat3, PpYLKTK, was previously shown to disrupt Stat3·Stat3 dimerization, thereby inducing antitumor cell effects (12). In pull-down assays, we demonstrated that S3I-201 disrupts the complex formation between two Stat3 monomers. S3I-201 preferentially interacts with Stat3 monomer protein over Stat1 or the Src family protein and has ½ the affinity for Stat5. In cells, the interactions with Stat3 will prevent de novo phosphorylation and activation of Stat3 monomer. Thus, S3I-201 mediates selective inhibition of Stat3 transcriptional activity and induces cell growth inhibition, loss of viability, and apoptosis of malignant cells that harbor constitutively active Stat3, as well as blocks v-Src transformation, events that are all consistent with the abrogation of Stat3 activation (11, 12, 22, 26, 27). The observation that overexpressed exogenous Stat3 SH2 domain, but not Stat3 N terminus in malignant cells, protects against S3I-201-induced apoptosis strongly supports the Stat3 SH2 domain as the _target of S3I-201. Our findings further suggest the antitumor cell effects of S3I-201 are mediated by suppressing aberrant Stat3-induced dysregulation of the cell-cycle control and the anti-apoptotic genes. Furthermore, in vivo antitumor effects of S3I-201 in human breast tumor xenografts establish the proof-of-concept for the therapeutic potential of S3I-201 as a Stat3 inhibitor in human tumors that harbor constitutively active Stat3.

Here, we report a Stat3 SH2 domain binder and an inhibitor of Stat3 signaling, which is structurally different from previously identified dimerization disrupters, peptides and peptidomimetics (11, 12), or other Stat3 inhibitors, such as the G-quartet oligonucleotides (28), peptide aptamers (29), platinum (IV) complexes (18, 19), cucurbitacin (30), and STA-21 (NSC 628869) (15). Although SH2 domains have been noted to have a high sequence similarity in their 100 amino acids (31, 32), S3I-201 has preference for Stat3 in that at concentrations that inhibit Stat3, S3I-201 has a low effect on Stat1 and Stat5, no interaction with the Src family proteins, weak inhibition of Erk1/2 and Shc activation, and low toxicity to cells with no aberrant Stat3. Our study supports computational modeling application in structure-based virtual screening for identifying Stat3 inhibitors from chemical libraries, and together with another report (15) is among the first to identify Stat3 inhibitors by this approach.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Reagents.

Normal mouse fibroblasts (NIH 3T3) and their counterparts transformed by v-Src (NIH 3T3/v-Src), v-Ras (NIH 3T3/v-Ras), or overexpressing the human EGFR (NIH 3T3/hEGFR), and the human breast cancer (MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-435, MDA-MB-453, and MDA-MB-468) cells have all been previously reported (11, 21, 22, 33). Cells were grown in DMEM containing 10% FBS. Antibodies C-136 and E23X for Stat1, C20 and C20X for Stat3, and L-20 and L-20X for Stat5A were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), and polyclonal anti-Src and anti-phosphoSrc antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA).

Transient Transfection of Cells and Treatment with Compound.

Twelve to 24 h after seeding, cells were transfected with the appropriate plasmids. For detailed procedure information, see SI Materials and Methods. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were untreated (0.05% DMSO) or treated with S3I-201 (100 μM) for an additional 24 h and harvested, and cytosolic extracts were prepared for luciferase assay, as described (11, 23), or cells were analyzed by annexin V binding and flow cytometry.

Cytosolic Extracts and Cell Lysate Preparation, Luciferase and β-Galactosidase Assay.

Cytosolic extract preparation from mammalian cells for luciferase (Promega, Madison, WI) and β-galactosidase assays, and from recombinant baculovirus-infected Sf-9 cells to obtain Stat1, Stat3, and Stat5 monomers, and Src proteins are as described previously (11, 23, 34).

Nuclear Extract Preparation, EMSAs, and Densitometric Analysis.

Nuclear extract preparations and EMSAs were carried out as previously described (21–23). The 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probes used were hSIE that binds Stat1 and Stat3 (22, 35) and MGFe for Stat1 and Stat5 binding (36, 37). Except where indicated, nuclear extracts were preincubated with compound for 30 min at room temperature before incubation with the radiolabeled probe. Bands corresponding to DNA-binding activities were scanned and quantified for each concentration of compound and plotted as a percentage of control (vehicle) against concentration of compound; the IC50 values were derived from these plots, as previously reported (11, 19).

Immunoprecipitation (IP) and Western Blotting.

Whole-cell lysates and tumor tissue lysates from pulverized tumor tissue were prepared in boiling SDS sample loading buffer to extract total proteins, as previously described (12, 18, 19, 22). For detailed procedure information and IP, see SI Materials and Methods.

Lck-SH2 Domain–Phosphopeptide-Binding Assay.

In vitro ELISA study involving the Lck-SH2-GST protein and the conjugate pTyr peptide, biotinyl-ε-Ac-EPQpYEEIEL-OH (Bachem Biosciences, King of Prussia, PA) was performed as previously described (20). For detailed procedure information, see SI Materials and Methods.

Soft-Agar Colony-Formation Assay.

Colony formation assays were carried out in six-well dishes, as described previously (11). Treatment with S3I-201 was initiated 1 day after seeding cells by adding 100 μl of medium with or without S3I-201 and repeating every 3 days, until large colonies were evident.

Measurement of Apoptosis by Flow Cytometry.

Proliferating cells were treated with or without S3I-201 for up to 48 h. In some cases, cells were first transfected with Stat3C, ST3-NT, or ST3-SH2 domain or mock-transfected for 24 h before treatment with compound for an additional 24–48 h. Cells were then detached and analyzed by annexin V binding (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol and flow cytometry to quantify the percent apoptosis.

Mice and in Vivo Tumor Studies.

Six-week-old female athymic nude mice were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN) and maintained in the institutional animal facilities approved by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. Athymic nude mice were injected in the left flank area s.c. with 5 × 106 human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells in 100 μl of PBS. After 5–10 days, tumors with a diameter of 3 mm were established. Animals were given S3I-201 i.v. at 5 mg/kg every 2 or 3 days for 2 weeks and monitored every 2 or 3 days. Animals were stratified so that the mean tumor sizes in all treatment were nearly identical. Tumor volume was calculated according to the formula V = 0.52 × a2× b, where a is the smallest superficial diameter and b is the largest superficial diameter.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all colleagues and members of our laboratory and the High-Throughput Screening and Chemistry Core Facility at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute for assistance with this work. This work was supported by National Cancer Institute Grant CA106439 (to J.T.).

Abbreviations

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- Erk

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- FLAG-ST3

FLAG-tagged Stat3

- NCI

National Cancer Institute

- YFP

yellow fluorescent protein.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0609757104/DC1.

References

- 1.Bromberg J. Breast Cancer Res. 2000;2:86–90. doi: 10.1186/bcr38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darnell JE., Jr Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:740–749. doi: 10.1038/nrc906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu H, Jove R. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:97–105. doi: 10.1038/nrc1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bromberg J, Darnell JE., Jr Oncogene. 2000;19:2468–2473. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowman T, Garcia R, Turkson J, Jove R. Oncogene. 2000;19:2474–2488. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turkson J, Jove R. Oncogene. 2000;19:6613–6626. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buettner R, Mora LB, Jove R. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:945–954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turkson J. Expert Opin Ther _targets. 2004;8:409–422. doi: 10.1517/14728222.8.5.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darnell JE. Nat Med. 2005;11:595–596. doi: 10.1038/nm0605-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shuai K, Horvath CM, Huang LH, Qureshi SA, Cowburn D, Darnell JE., Jr Cell. 1994;76:821–828. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90357-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turkson J, Ryan D, Kim JS, Zhang Y, Chen Z, Haura E, Laudano A, Sebti S, Hamilton AD, Jove R. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45443–45455. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turkson J, Kim JS, Zhang S, Yuan J, Huang M, Glenn M, Haura E, Sebti S, Hamilton AD, Jove R. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:261–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Becker S, Groner B, Muller CW. Nature. 1998;394:145–151. doi: 10.1038/28101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shao H, Xu X, Mastrangelo MA, Jing N, Cook RG, Legge GB, Tweardy DJ. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18967–18973. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314037200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song H, Wang R, Wang S, Lin J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4700–4705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409894102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friesner R, Banks J, Murphy R, Halgren T, Klicic J, Mainz D, Repasky M, Knoll E, Shelbey M, Perry J, et al. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1739–1749. doi: 10.1021/jm0306430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halgren T, Murphy R, Friesner R, Beard H, Frye L, Pollard W, Banks J. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1750–1759. doi: 10.1021/jm030644s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turkson J, Zhang S, Palmer J, Kay H, Stanko J, Mora LB, Sebti S, Yu H, Jove R. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:1533–1542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turkson J, Zhang S, Mora LB, Burns A, Sebti S, Jove R. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32979–32988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502694200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee TR, Lawrence DS. J Med Chem. 2000;43:1173–1179. doi: 10.1021/jm990462r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu CL, Meyer DJ, Campbell GS, Larner AC, Carter-Su C, Schwartz J, Jove R. Science. 1995;269:81–83. doi: 10.1126/science.7541555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia R, Bowman TL, Niu G, Yu H, Minton S, Muro-Cacho CA, Cox CE, Falcone R, Fairclough R, Parson S, et al. Oncogene. 2001;20:2499–2513. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turkson J, Bowman T, Garcia R, Caldenhoven E, De Groot RP, Jove R. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2545–2552. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galbaugh T, Cerrito MG, Jose CC, Cutler ML. BMC Cell Biol. 2006;7:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-7-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bromberg JF, Wrzeszczynska MH, Devgan G, Zhao Y, Pestell RG, Albanese C, Darnell JE., Jr Cell. 1999;98:295–303. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81959-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Catlett-Falcone R, Landowski TH, Oshiro MM, Turkson J, Levitzki A, Savino R, Ciliberto G, Moscinski L, Fernandez-Luna JL, Nuñez G, et al. Immunity. 1999;10:105–115. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mora LB, Buettner R, Seigne J, Diaz J, Ahmad N, Garcia R, Bowman T, Falcone R, Fairclough R, Cantor A, et al. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6659–6666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jing N, Li Y, Xu X, Sha W, Li P, Feng L, Tweardy DJ. DNA Cell Biol. 2003;22:685–696. doi: 10.1089/104454903770946665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagel-Wolfrum K, Buerger C, Wittig I, Butz K, Hoppe-Seyler F, Groner B. Mol Cancer Res. 2004;2:170–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blaskovich MA, Sun J, Cantor A, Turkson J, Jove R, Sebti SM. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1270–1279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheinerman FB, Al-Lazikani B, Honig B. J Mol Biol. 2003;334:823–841. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuriyan J, Cowburn D. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1997;26:259–288. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.26.1.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson PJ, Coussens PM, Danko AV, Shalloway D. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:1073–1083. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.5.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Y, Turkson J, Carter-Su C, Smithgall T, Levitzki A, Kraker A, Krolewski JJ, Medveczky P, Jove R. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:24935–24944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002383200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagner M, Kleeff J, Friess H, Buchler MW, Korc M. Pancreas. 1999;19:370–376. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199911000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gouilleux F, Moritz D, Humar M, Moriggl R, Berchtold S, Groner B. Endocrinology. 1995;136:5700–5708. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.12.7588326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seidel HM, Milocco LH, Lamb P, Darnell JE, Jr, Stein RB, Rosen J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3041–3045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.