Abstract

The fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP), the functional absence of which causes fragile X syndrome, is an RNA-binding protein that has been implicated in the regulation of local protein synthesis at the synapse. The mechanism of FMRP's interaction with its _target mRNAs, however, has remained controversial. In one model, it has been proposed that BC1 RNA, a small non-protein-coding RNA that localizes to synaptodendritic domains, operates as a requisite adaptor by specifically binding to both FMRP and, via direct base-pairing, to FMRP _target mRNAs. Other models posit that FMRP interacts with its _target mRNAs directly, i.e., in a BC1-independent manner. Here five laboratories independently set out to test the BC1–FMRP model. We report that specific BC1–FMRP interactions could be documented neither in vitro nor in vivo. Interactions between BC1 RNA and FMRP _target mRNAs were determined to be of a nonspecific nature. Significantly, the association of FMRP with bona fide _target mRNAs was independent of the presence of BC1 RNA in vivo. The combined experimental evidence is discordant with a proposed scenario in which BC1 RNA acts as a bridge between FMRP and its _target mRNAs and rather supports a model in which BC1 RNA and FMRP are translational repressors that operate independently.

Keywords: fragile X syndrome, non-protein-coding RNAs, translational control

Small non-protein-coding RNAs perform important functions in the regulation of eukaryotic gene expression (1). In the mammalian central nervous system, they have been implicated in promoting organism–environment interactions (2). Small untranslated BC1 RNA is a translational repressor that is thought to participate in the regulation of local protein synthesis at the synapse (2, 3). BC1 RNA represses translation by _targeting assembly of 48S initiation complexes (4). Interacting with eukaryotic initiation factor 4A (eIF4A) and poly(A) binding protein (PABP) (4–6), BC1 RNA prevents recruitment of the 43S preinitiation complex to the mRNA. _targets of BC1-mediated repression are those mRNAs that depend on the eIF4 family of factors for efficient initiation (4).

Fragile X syndrome is caused by the functional absence of fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) (7, 8). Consensus has developed over recent years that FMRP is, like BC1 RNA, a translational repressor that is active in postsynaptic microdomains (7, 9, 10). However, in contrast to BC1 RNA, FMRP is associated with polysomes (11–15), indicating that BC1 RNA and FMRP operate at different levels in the translation pathway.

In an alternative model, it has been proposed that BC1 RNA and FMRP interact directly with each other (16, 17). In this scenario, BC1 RNA (i) physically binds to FMRP, (ii) directly interacts, by base-pairing of its 5′ domain, with select mRNAs that are FMRP _targets, and (iii) acts as a bridge between FMRP and such _target mRNAs, thus serving as a requisite adaptor (16, 17).

The above two models cannot be reconciled. We, five independent groups with a longstanding interest in the molecular biology of BC1 RNA and/or FMRP, therefore reexamined the issue of FMRP–BC1–mRNA interactions in vitro and in vivo. We report that no specific direct interaction can be documented and that BC1 RNA is not required as an adaptor to link previously reported _target mRNAs to FMRP.

Results

In Vitro Interactions of BC1 RNA with FMRP.

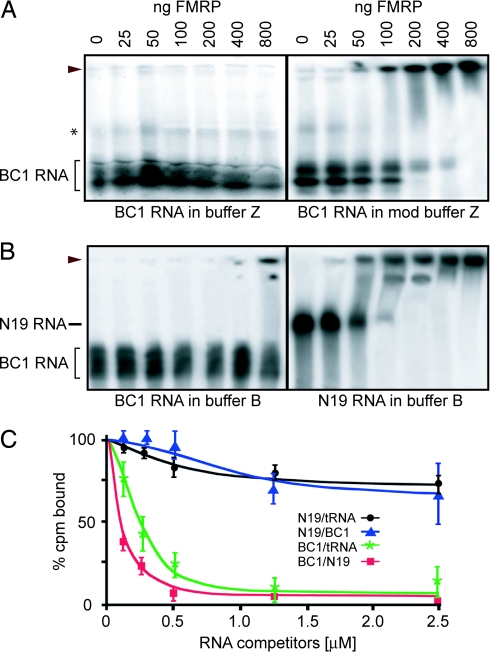

FMRP has been reported to bind to BC1 RNA under conditions of exceptionally high salt concentrations (750 mM NaCl plus 100 mM KCl) (17). We performed EMSAs to reassess binding of BC1 RNA to FMRP as a function of salt concentration in vitro. In the presence of 850 mM monovalent cations (buffer Z) (17) we were unable to detect any mobility shift of BC1 RNA over a wide range of FMRP concentrations (Fig. 1A). When salt concentrations in buffer Z were reduced to 100 mM KCl (modified buffer Z), a mobility shift of BC1 RNA became apparent at FMRP levels of 100 ng per assay and higher (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Binding of FMRP to BC1 RNA is nonspecific. (A and B) EMSA was performed with 32P-labeled BC1 RNA or N19 RNA and increasing amounts of FMRP as indicated. Monovalent cations were used as follows: 750 mM NaCl plus 100 mM KCl (A Left, buffer Z), 100 mM KCl (A Right, mod buffer Z), or 150 mM KCl (B, buffer B). (A) In the absence of competitor RNA, binding of BC1 RNA to FMRP was observed under conditions of moderate but not high salt concentrations. (B) Binding of BC1 RNA, but of N19 RNA, was abolished in the presence of 100 ng/μl tRNA. Arrowheads indicate FMRP–RNA complexes. In addition, the positions of BC1 RNA and N19 RNA in the absence of FMRP are indicated. The asterisk indicates a minor species of differentially folded BC1 RNA formed under conditions of high salt concentrations. In general, whereas in vitro transcribed BC1 RNA resolves as a single band in denaturing gels, several bands reflecting different conformers are visualized in native gels, depending on salt concentrations. (C) Competition experiments for FMRP binding to BC1 RNA and N19 RNA were performed by using filter binding assays. Each data point represents the mean of three experimental values. The key lists RNAs in the format labeled/competitor. Error bars represent SEM. The data in this figure are from the E.W.K. laboratory.

Notably, however, buffer Z does not use competitor RNA to reduce unspecific binding. EMSAs were therefore repeated under conditions of physiological salt concentrations (150 mM KCl, buffer B) (18) in the presence of 100 ng/μl tRNA (Fig. 1B). In this case, no mobility shift was observed except at an extreme level of FMRP (800 ng). N8 RNA, an FMR1 mRNA segment that does not specifically bind to FMRP (19), readily displaced BC1 RNA from FMRP in a manner analogous to tRNA (data not shown). In contrast, when we used N19 RNA, an FMR1 mRNA segment that contains a G-quartet-forming structure and is a genuine FMRP _target RNA (19), tRNA did not compete because a clear shift was observed in its presence over the entire FMRP concentration range (Fig. 1B).

For a quantitative assessment of BC1–FMRP interactions, we used a filter binding RNA competition assay (20) that allows appraisal of nonspecific binding contributions. As shown in Fig. 1C, addition of tRNA or BC1 RNA to the reaction had little effect on the binding of N19 RNA to FMRP, demonstrating that BC1 RNA is as ineffective as tRNA at displacing N19 RNA, a bona fide FMRP _target RNA. In contrast, both tRNA and N19 RNA displaced BC1 RNA from FMRP, as evidenced by a substantial reduction of binding in the presence of either competitor RNA (Fig. 1C). The data show that whereas N19 RNA, BC1 RNA, and tRNA appear to bind to the same site on FMRP, BC1 RNA but not N19 RNA is competed off this site by tRNA. In view of the these data, it is concluded that in vitro BC1–FMRP interactions are nonspecific and are of low affinity. It is possible that many RNAs bind to FMRP in such nonspecific, low-affinity manner in vitro (5).

Interactions of BC1 RNA with FMRP _target mRNAs.

We next turned to the question of whether BC1 RNA physically interacts with mRNAs that are _targets of FMRP regulation. Zalfa and colleagues (16, 17) proposed that the 5′ BC1 domain directly interacts, via base-pairing, with such FMRP _target mRNAs and that BC1 RNA thus bridges these mRNAs and FMRP. These authors probed BC1–mRNA interactions by annealing biotinylated BC1 RNA with total RNA from mouse brain and by subsequently amplifying RNAs that were recovered from streptavidin beads (17).

To reexamine this issue, we replicated the previously reported experiments under identical conditions and probed for FMRP _target and non_target RNAs (Fig. 2). Two approaches were used in parallel in these experiments. (i) Biotinylated BC1 RNA was incubated with total RNA isolated from mouse brain, as described (17). (ii) In addition, we used a biotinylated oligodeoxyribonucleotide complementary to the 3′ BC1 domain. This probe (called bio-unique) has recently been used for the specific capture, per affinity purification, of BC1 RNA from total mouse brain RNA (21). It will capture endogenous, native BC1 RNA together with any mRNA that may be bound to its 5′ domain, an advantage over the first approach, in which any mRNA bound to endogenous BC1 RNA has to be competed off and captured by externally added biotinylated BC1 RNA. For further controls, total mouse brain RNA was prepared from BC1−/− [knockout (KO)] animals (22) in addition to WT animals.

Fig. 2.

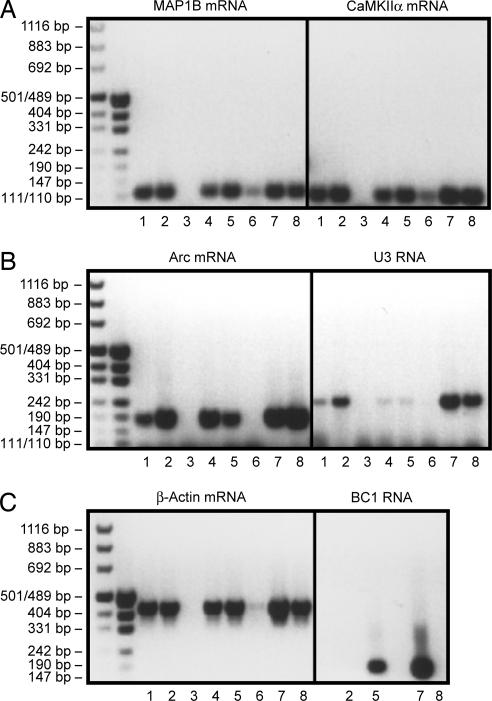

BC1 RNA does not specifically interact with FMRP _target mRNAs. Total RNA isolated from WT C57BL/6 mouse brains and from BC1−/− KO mouse brains was incubated with biotinylated BC1 RNA or an oligonucleotide complementary to the 3′ BC1 RNA region (bio-unique). The experimental protocol of Zalfa et al. (17) was followed throughout. RNA was extracted and RT-PCR was performed by using primers specific for the respective RNA species indicated. Lanes were loaded as follows: lane 1, total RNA from KO BC1−/− mouse brain was annealed to biotinylated BC1 RNA; lane 2, total RNA from KO BC1−/− mouse brain was annealed to biotinylated bio-unique oligonucleotide; lane 3, total RNA from KO BC1−/− mouse brain was mock-annealed to streptavidin magnetic beads; lane 4, total RNA from WT mouse brain was annealed to biotinylated BC1 RNA; lane 5, total RNA from WT mouse brain was annealed to biotinylated bio-unique oligonucleotide; lane 6, total RNA from WT mouse brain was mock-annealed to streptavidin magnetic beads; lane 7, total RNA from WT mouse brain was used as template for RT-PCR with specific oligonucleotides as a positive control for each experiment; lane 8, total RNA from KO BC1−/− mouse brain was used as template for RT-PCR with specific oligonucleotides as a positive control for each experiment. The data in this figure are from the J.B. laboratory.

As is shown in Fig. 2, we obtained RT-PCR products of microtubule-associated protein 1B (MAP1B), calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase IIα (CaMKIIα), and Arc (Arg-3.1)mRNAs after capture with biotinylated BC1 RNA from WT and BC1 KO mouse brain total RNA (Fig. 2 A and B, lanes 1 and 4). Fig. 2C Right, lane 8, confirms that BC1 RNA is absent in total RNA from BC1 KO brains. The three FMRP _target mRNAs were also captured and amplified from WT mouse brain total RNA using the bio-unique oligonucleotide that is directed against the 3′ BC1 domain (lane 5 in Fig. 2 A and B). At the same time, however, both approaches also yielded amplification products of RNAs that have not been reported to be FMRP _targets, i.e., β-actin mRNA and U3 snoRNA (Fig. 2 B and C). Both RNAs are ubiquitous RNAs, the latter a small nucleolar RNA that participates in pre-rRNA processing. Neither RNA exhibits any significant sequence complementarity to BC1 RNA. The combined results let us conclude that the BC1 capture approaches used in this and a previous article (17) do not discriminate between FMRP _target and non_target mRNAs.

It appears that this lack of discrimination is the result of nonspecific interactions. Thus, we noted that, under the experimental conditions used and previously reported, MAP1B and CaMKIIα mRNAs also bind, albeit with lower apparent affinity, to the streptavidin matrix (Fig. 2 A and B, lane 6). Furthermore, when using the bio-unique oligonucleotide directed against the 3′ BC1 domain, RNAs were captured and amplified even from BC1 KO mouse brain total RNA (Fig. 2, lane 2). The results show that the chosen experimental routine is prone to yielding nonspecific amplification products.

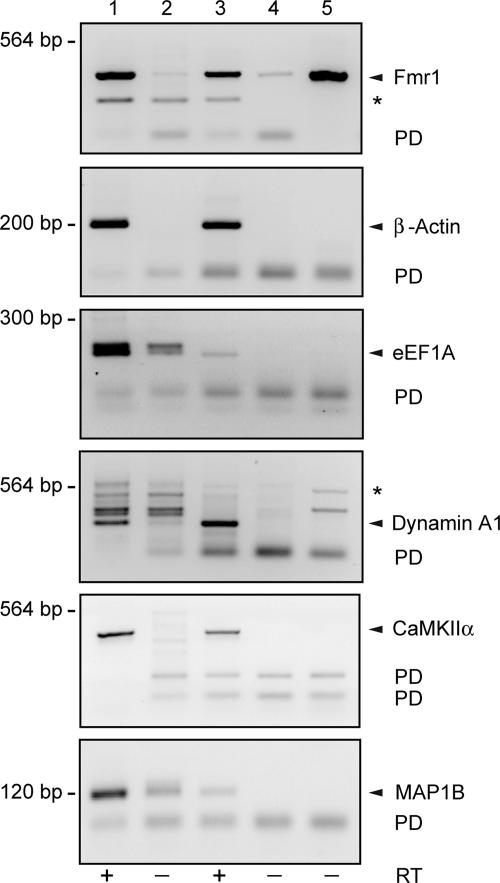

The central domain of BC1 RNA contains a single-stranded homopolymeric A segment of 22 nucleotides. We therefore hypothesized that, in capture experiments in vitro, BC1 RNA may interact, by base-pairing of at least part of this A22 segment, with RNAs that contain U-rich segments. To test this hypothesis, we annealed total RNA from mouse brain to poly(A) RNA agarose (Fig. 3). Bound RNA was recovered, converted to cDNA, and amplified with gene-specific primers [supporting information (SI) Materials and Methods] using previously described conditions (17). From total mouse brain RNA we amplified Fmr1, eukaryotic elongation factor 1A (eEF1A), CaMKIIα, and MAP1B mRNAs (Fig. 3, lane 1). Each of these mRNAs was also present in the poly(A) annealed fraction (Fig. 3, lane 3). These four mRNAs are FMRP _targets that contain U-rich segments (23). However, we also recovered β-actin and dynamin A1 mRNAs (Fig. 3), mRNAs that feature U-rich segments but are not known to be FMRP _target mRNAs (23). The experimental approach therefore selects U-rich mRNAs regardless of whether they are FMRP _targets or not. The strength of the band representing the respective captured mRNA (Fig. 3, lane 3) corresponds to the length of U-element(s) in that mRNA (see SI Table 1). As a further control, we performed the annealing reaction in the presence of excess free poly(A) RNA to verify that amplification did not arise from contaminating unbound RNA (see SI Fig. 6).

Fig. 3.

U-rich FMRP _target and non_target mRNAs bind to poly(A) RNA. Mouse cortex total RNA (1 μg) was annealed to 20 μl of poly(A) RNA agarose resin, and bound RNA was converted to cDNA and amplified (see Materials and Methods). Results are shown in lane 3. Lane 4 shows controls performed in the absence of reverse transcriptase. Lanes 1 and 2 show amplifications of cDNA from total RNA (1 μg) after omission of the poly(A) binding step (reverse transcriptase omitted in lane 2). Lane 5 is an amplification of pET21A-FMRP plasmid DNA (10 ng). PD indicates primer–dimer bands, and asterisks indicate nonspecific bands. In the absence of poly(A) annealing (lanes 1 and 2), a minor band was in some cases apparent both in +RT and −RT lanes (e.g., dynamin A1 amplification). Bands in the −RT lane may indicate amplification from carryover of genomic DNA. However, such bands were not observed after poly(A) annealing. The data in this figure are from the R.B.D. laboratory.

Taken together, the above results lead to the conclusion that the chosen RNA capture and amplification procedure (17) is unable to substantiate any specific binding of BC1 RNA to FMRP _target mRNAs. Various RNAs are captured and amplified in this procedure because of (i) lack of specificity of the procedure per se and (ii) the selection of U-rich RNAs by an A-rich segment in BC1 RNA.

On the Interaction of BC1 RNA, FMRP, and FMRP _target mRNAs in Vivo.

The model proposed by Zalfa and colleagues (16, 17) specifically predicted that BC1 RNA is required as an adaptor to link FMRP with its _target mRNAs. If so, FMRP should be unable to interact with such _target mRNAs in the absence of BC1 RNA. We tested this hypothesis in vivo using BC1−/− animals (22).

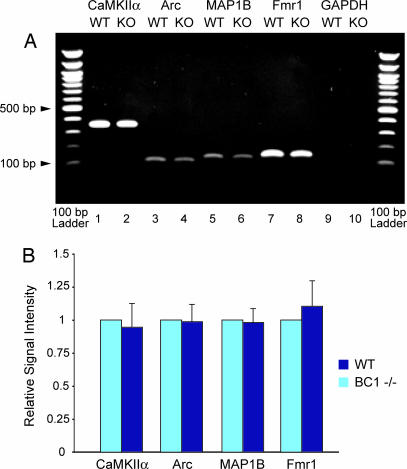

We performed immunoprecipitation (IP) with brain extracts prepared from WT and BC1−/− (KO) animals, using FMRP-specific monoclonal antibody 7G1-1 (24). IP RNA was amplified by RT-PCR with mRNA-specific primers. We probed for CaMKIIα, Arc, and MAP1B mRNAs, i.e., those mRNAs that Zalfa et al. (17) proposed to be physically linked by BC1 RNA to FMRP. In addition, we probed for Fmr1 mRNA, another FMRP _target mRNA, and GAPDH mRNA, a FMRP non_target control mRNA (24).

As shown in Fig. 4, FMRP _target mRNAs, but not non_target GAPDH mRNA, were amplified from IP RNA. Notably, levels of none of the FMRP _target mRNAs that were amplified from IP RNA were found to differ discernibly between preparations from WT and BC1 KO brains (Fig. 4A). Quantitative and statistical analysis did not reveal any significant differences, for any of the probed FMRP _target mRNAs, between immunoprecipitated RNAs derived from WT and BC1 KO brains, respectively (Fig. 4B). The data show that FMRP associates with _target mRNAs in the absence of BC1 RNA, a result incompatible with a requirement for BC1 RNA to provide a physical link between FMRP and its _target mRNAs, as postulated by Zalfa and colleagues (16, 17).

Fig. 4.

FMRP associates with _target mRNAs in vivo in the absence of BC1 RNA. Using monoclonal anti-FMRP antibody 7G1-1, coimmunoprecipitation was performed in brain extracts from WT and BC1−/− (KO) animals. (A) RNA was extracted and assayed for CaMKIIα, Arc, MAP1B, and Fmr1 mRNAs (i.e., FMRP _target mRNAs) and for GAPDH mRNA (not an FMRP _target). All examined FMRP _target mRNAs were indistinguishably identified in WT and KO brains. Expected PCR product sizes were as follows: CaMKIIα, 354 bp; Arc, 86 bp; MAP1B, 119 bp; Fmr1, 134 bp; GAPDH, 233 bp. (B) Paired Student's t tests revealed no significant difference in FMRP _target mRNA levels between WT and KO animals (P > 0.8 for each _target mRNA; n ≥ 4 in all cases). For each group, the relative WT level was normalized to 1. The data in this figure are from the H.T. laboratory.

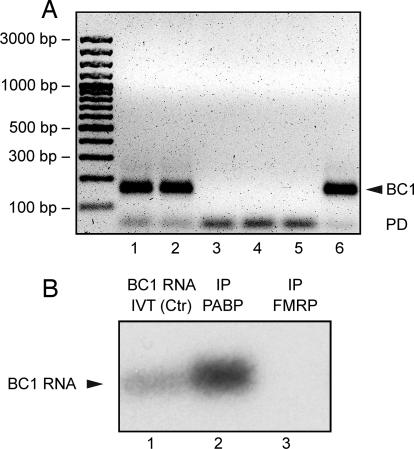

Does BC1 RNA associate with FMRP in vivo? We performed IP experiments to address this question. FMRP (F-IP) and PABP (P-IP) were IP-_targeted in whole-brain homogenates prepared from fmr1−/− (KO) and WT mice. PABP was chosen as a positive control because it has previously been shown to interact with BC1 RNA (4, 25, 26). F-IP from fmr1−/− (KO F-IP) brains was performed to exclude the possibility of unspecific RNA precipitation. As an additional negative control, we performed IP with irrelevant IgGs (IgG-IP).

Extracted IP RNA was probed for BC1 RNA by RT-PCR and real-time PCR. The RT-PCR data show that BC1 RNA was identified in P-IP RNA but not in F-IP RNA (Fig. 5A). In contrast, FMRP _target PSD-95 mRNA (27) was readily detectable in both F-IP and P-IP (SI Fig. 7). These results were independently confirmed by real-time PCR performed with RNA from three independent tissue preparations. A high P-IP vs. F-IP ΔCT value of 14.01 ± 0.60 confirms that in WT brains BC1 RNA is detectable in PABP but not in FMRP immunoprecipitates. In addition, ΔCT values for KO F-IP vs. WT F-IP of 0.60 ± 0.62 and for WT IgG-IP vs. WT F-IP of 0.46 ± 0.29, i.e., close to 0 in either case, imply that BC1 levels in FMRP immunoprecipitates from WT brains are indistinguishable from background levels. Finally, when detecting PSD-95 mRNA, a ΔCT value for WT F-IP vs. KO F-IP of 3.01 ± 0.83 shows that the antibody efficiently immunoprecipitates PSD-95 mRNA associated with FMRP from WT but not KO brain homogenates. Thus, the lack of BC1 RNA in WT F-IP is not due to a general failure of the antibody to precipitate FMRP–RNA complexes, but to a genuine absence of BC1 RNA from such complexes.

Fig. 5.

BC1 RNA does not associate with FMRP in vivo. (A) RT-PCR was performed with primers specific for BC1 RNA. Template RNA was extracted from input material obtained with WT (lane 1) and fmr1 KO (lane 2) brains, from irrelevant IgG-IP with WT brains (lane 3), from FMRP-IP (F-IP) with WT (lane 4) and fmr1 KO (lane 5) brains, and from PABP-IP (P-IP) with WT brains (lane 6). The BC1 PCR product (arrowhead) is detected in both input lanes and in the P-IP lane, but not in F-IP or IgG-IP lanes. PCR products marked by PD are primer dimers. The data in A are from the S.K. laboratory. (B) Northern hybridization was performed to probe for BC1 RNA in F-IP RNA and P-IP RNA. Whereas a strong signal was observed in the P-IP lane, no signal was detected in the F-IP lane (even after overexposure). In vitro transcribed BC1 RNA (10 ng) was used for reference (BC1 Ctr).The data in B are from the H.T. laboratory.

The above experiments were performed with polyclonal anti-FMRP antibody H-120. Analogous work was performed, in separate experiments in a different laboratory, with monoclonal anti-FMRP antibody 7G1-1. Again, an anti-PABP antibody was used for positive control IP. In this case, F-IP RNA and P-IP RNA were probed for BC1 RNA by filter (Northern) hybridization (25). The results (Fig. 5B) demonstrate again that BC1 RNA is not detectable in FMRP immunoprecipitates although its presence in PABP immunoprecipitates is clearly evident. The combined data therefore show that BC1 RNA does not associate with FMRP in vivo.

Discussion

BC1 RNA and FMRP are translational repressors that have been implicated in the modulation of postsynaptic protein repertoires in neurons (2, 3, 9, 28). BC1 RNA inhibits recruitment of 43S preinitiation complexes to mRNAs; it therefore _targets translation particularly of mRNAs with structured 5′ UTRs that require eIF4A-mediated unwinding (4, 5). FMRP _targets, on the other hand, include mRNAs with G-quartets (19, 20), kissing complexes (29), and U-rich modules (30), among others. Although the mode of action of FMRP-mediated translational repression is currently less well established, it would appear that both repressors may _target relatively large subsets of neuronal mRNAs. Therefore, BC1- and FMRP-mediated translational repression may be directed at overlapping sets of _target mRNAs.

It is critically important, for this reason, to elucidate the nature of BC1–FMRP interactions, if any, and their relevance for FMRP _target recognition. The model proposed by Zalfa and colleagues (16, 17) makes three distinct and directly testable predictions. (i) BC1 RNA specifically and directly binds to FMRP. (ii) Through its 5′ domain, BC1 RNA specifically and directly binds to various FMRP _target mRNAs. (iii) BC1 RNA is required as an adaptor, a physical link, between FMRP and a _target mRNA. Here we tested these predictions experimentally.

(i) No specific binding of BC1 RNA to FMRP was documented either in vitro or in vivo. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments identified BC1 RNA in PABP IP RNA but failed to do so in FMRP IP RNA. These experiments were performed by two different laboratories—not cognizant of each other's work until after completion—using two different validated anti-FMRP antibodies as well as different precipitation and RNA detection methods. Even when highly sensitive techniques (real-time PCR or RT-PCR with 40 amplification cycles) were used, BC1 RNA was undetectable in FMRP IP RNA. In clear contrast, bona fide FMRP _target mRNAs were coimmunoprecipitated by both anti-FMRP antibodies (Fig. 4 and SI Fig. 7).

Low amounts of BC1 RNA were earlier reported in FMRP IP RNA (31); however, slightly higher amounts were detected in the same experiment in MAP2 IP RNA. Because MAP2 is not known as an RNA binding protein, the data suggest that this result occurred from nonspecific precipitation or amplification.

In vitro, BC1 RNA associates with FMRP in a nonspecific manner. Contrary to previous claims (17), no interaction is observed under high concentrations of monovalent cations (850 mM). Under physiological salt concentrations, BC1 RNA associates with FMRP, but this association is nonspecific because it is easily abolished by FMRP non_target RNAs such as tRNA or N8 RNA. Similarly, under lower than physiological salt concentrations (30 mM NaCl) in the absence of competitor RNA (32), BC1–FMRP interactions are indistinguishable from tRNA–FMRP interactions.

In summary, there is no basis to the claim that BC1 RNA binds to FMRP in any specific way, either in vitro or in vivo.

(ii) The 5′ BC1 domain has been suggested to base pair directly with complementary regions in FMRP _target mRNAs (16, 17). However, specific interactions between BC1 RNA and such FMRP _target mRNAs could not be corroborated in the present work. The 5′ BC1 domain is a stable stem–loop structure (33). The stability of this domain makes it unlikely that single-stranded segments of sufficient length would be available for base-pairing with other RNAs. In contrast, the single-stranded A-rich segment in the central BC1 domain is readily accessible, at least in vitro (33).

(iii) The mRNAs encoding MAP1B, Arc, and CaMKIIα have been proposed to require BC1 RNA as a guide to _target them to FMRP (16, 17). In BC1−/− animals, however, we found that FMRP is associated with these _target mRNAs in a manner indistinguishable from WT animals. BC1 RNA therefore does not appear to perform a requisite function in guiding these _target mRNAs to FMRP.

In the absence of specific interactions between BC1 RNA and either FMRP or FMRP _target mRNAs, and of a requirement for BC1 RNA to guide mRNAs to FMRP, we cannot but conclude that the functional roles of BC1 RNA and FMRP as translational repressors are executed independent of each other. Neither does BC1 RNA require FMRP for its repressor function, nor vice versa. It should be emphasized, however, that these statements do not extend to miRNAs. FMRP has been implicated in the miRNA pathway (reviewed in refs. 3 and 34), but these RNAs appear to operate via modes of action that are functionally distinct from BC1 RNA.

In summary, the available data are most readily reconciled with the notion that, in the local translation pathway, BC1 RNA and FMRP operate independently. Thus, whereas BC1 RNA represses translation initiation at the level of 48S complex formation, FMRP would _target a subsequent step downstream from BC1 RNA. We propose that multiple translational repressors may be required at the synapse to ensure that an adequate activation–repression balance is maintained over time (35).

Materials and Methods

Sequences of oligonucleotides used as PCR primers are listed in SI Materials and Methods.

EMSA and Filter Binding Assays.

His-tagged FMRP was expressed in Escherichia coli as described (36). BC1 and N19 RNAs were 32P-labeled at 40,000 cpm per reaction (≈10 ng) and were incubated with increasing amounts of FMRP (0–800 ng per assay) in 20 μl of 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.9), 100 mM KCl, 750 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 7 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM DTT, 5% glycerol, 1 μg/μl BSA, and 1.33 μg/μl heparin (buffer Z) (17) or in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.6), 150 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.2 units/μl RNase inhibitor (Amersham), 100 ng/μl total yeast tRNA, and 100 ng/μl BSA (buffer B) (18). If competitor RNAs were used, they were preincubated with FMRP for 10 min before addition of the labeled RNA.

Filter binding assays were performed as described (18). For EMSA experiments, RNA–protein complexes were resolved on 5% polyacrylamide gels. It should be noted that under the conditions used RNA–FMRP complexes are typically detected near the top of the gel (see also refs. 16 and 32). We presume that such bands represent homomeric FMRP complexes that bind RNA. However, in the interest of experimental conditions being consistent with previous work (16), we refrained from using dissociating agents such as urea.

In Vitro Annealing to Mouse Brain RNA.

Biotinylated BC1 RNA was bound to streptavidin-conjugated magnetic beads and incubated with total mouse brain RNA as described (17). In separate experiments, we used 100 pmol of a biotinylated oligonucleotide complementary to 3′ BC1 domain (bio-unique) (21). First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed by using Transcriptor reverse transcriptase (Roche Diagnostics) and random hexamer oligonucleotides, followed by 30 cycles of PCR amplification (17) with RNA-specific oligonucleotide primers.

Hybridization of mRNAs to poly(A) RNA.

Total RNA (1 μg) from mouse cortex was incubated with 20 μl of poly(A) RNA agarose resin (Sigma) at 80°C for 5 min in 20 μl of 10 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.5), 2 mM MgCl2, 400 mM NaCl, and 0.2% SDS (17) and allowed to cool at room temperature for 2 h. Nonbound material was removed with two washes (100 μl each) of the same buffer. Bound RNA was isolated with Tri-Reagent; after precipitation, half was converted to cDNA with the SuperScript III first-strand synthesis system (Invitrogen), and the other half was incubated in the absence of reverse transcriptase. Samples (1/20 aliquots) were amplified by PCR for the indicated mRNAs.

Immunoprecipitation.

IP with anti-FMRP was performed (i) to probe for FMRP _target mRNAs in the presence or absence of BC1 RNA and (ii) to probe for an association of BC1 RNA with FMRP. In the first approach we used a modified version of a previously published procedure (37). Dynabeads protein G slurry (Invitrogen) was washed with 100 mM sodium phosphate (pH 8.0) and incubated overnight at 4°C with 2.5 μg/μl monoclonal anti-FMRP 7G1-1 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) (24). Beads were incubated with brain extracts at 4°C for 2 h and washed extensively, and RNA was extracted by using TRIzol (Invitrogen).

In the second approach (variant S.K. laboratory), aliquots of brain extracts were incubated overnight with 15 μg of polyclonal anti-FMRP H-120 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), affinity-purified polyclonal anti-PABP (38) (a gift of Evita Mohr, Institute of Anatomy I, Cellular Neurobiology, University Hospital Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany), or rabbit IgG (Sigma–Aldrich). Samples were incubated for 40 min with 100 μl of preblocked protein A agarose. Beads were precipitated, washed, resuspended, and treated with proteinase K (Roche). RNA was extracted by using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). In the second approach (variant H.T. laboratory), monoclonal anti-FMRP 7G1-1 was used. The anti-PABP used was described earlier (4); in addition, a newly generated affinity-purified polyclonal anti-PABP was used with identical results. IP methods used were those described for the first approach.

The fact that the laboratories contributing to this article used different materials and methods, as exemplified here by IP methods, is a consequence of their not being aware of each other's work. Regardless of the different methods used, however, the results obtained were congruent. Detailed IP methods are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

We thank Dr. Jennifer Darnell (The Rockefeller University, New York) for advice on FMRP IP methods, Dr. Gianfranco Risuleo (Università di Roma “La Sapienza,” Rome) for advice on RT-PCR methods, and Drs. Hervé Moine (IGBMC, Université Louis Pasteur, Strasbourg, France) and Barbara Bardoni (Università de Nice Sophia-Antipolis, Nice, France) for N8 and N19 plasmids. Statistical consultation was provided by Dr. Jeremy Weedon (State University of New York Brooklyn Scientific Computing Center). A.I. is a Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health scholar sponsored by National Institutes of Health Grant HD43428. B.T. is the recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship from the Fragile X Research Foundation of Canada/Canadian Institutes of Health Research Partnership Challenge Fund program. This work was supported in part by Nationales Genomforschungsnetz Grant 0313358A (to J.B.), the Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene (R.B.D.), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (E.W.K.), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grants Ki 488/2-6 and KR1321/4-1 (S.K.), Fritz Thyssen Stiftung Grant Az. 10.05.2.185 (to S.K.), and National Institutes of Health Grant NS046769 (to H.T.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0710991105/DC1.

References

- 1.Barciszewski J, Erdmann VA, editors. Noncoding RNAs: Molecular Biology and Molecular Medicine. Georgetown, TX: Landes Bioscience; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao X, et al. Noncoding RNAs in the mammalian central nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:77–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kindler S, Wang H, Richter D, Tiedge H. RNA transport and local control of translation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:223–245. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.122303.120653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang H, et al. Dendritic BC1 RNA: Functional role in regulation of translation initiation. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10232–10241. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10232.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang H, et al. Dendritic BC1 RNA in translational control mechanisms. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:811–821. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kondrashov AV, et al. Inhibitory effect of naked neural BC1 RNA or BC200 RNA on eukaryotic in vitro translation systems is reversed by poly(A)-binding protein (PABP). J Mol Biol. 2005;353:88–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Donnell WT, Warren ST. A decade of molecular studies of fragile X syndrome. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:315–338. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bardoni B, Davidovic L, Bensaid M, Khandjian EW. The fragile X syndrome: Exploring its molecular basis and seeking a treatment. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2006;8:1–16. doi: 10.1017/S1462399406010751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sung YJ, Denman RB. The Molecular Basis of Fragile X Syndrome. Trivandrum, India: Research Signpost; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfeiffer BE, Huber KM. Fragile X mental retardation protein induces synapse loss through acute postsynaptic translational regulation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3120–3130. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0054-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiler IJ, et al. Fragile X mental retardation protein is translated near synapses in response to neurotransmitter activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5395–5400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ceman S, et al. Phosphorylation influences the translation state of FMRP-associated polyribosomes. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:3295–3305. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davidovic L, Huot ME, Khandjian EW. Lost once, the Fragile X Mental Retardation protein is now back onto brain polyribosomes. RNA Biol. 2005;2:1–3. doi: 10.4161/rna.2.1.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stefani G, Fraser CE, Darnell JC, Darnell RB. Fragile X mental retardation protein is associated with translating polyribosomes in neuronal cells. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7272–7276. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2306-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khandjian EW, et al. Biochemical evidence for the association of fragile X mental retardation protein with brain polyribosomal ribonucleoparticles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13357–13362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405398101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zalfa F, et al. FMRP binds specifically to the brain cytoplasmic RNAs BC1/BC200 via a novel RNA binding motif. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33403–33410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504286200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zalfa F, et al. The fragile X syndrome protein FMRP associates with BC1 RNA and regulates the translation of specific mRNAs at synapses. Cell. 2003;112:317–327. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bechara E, et al. Fragile X related protein 1 isoforms differentially modulate the affinity of fragile X mental retardation protein for G-quartet RNA structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:299–306. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schaeffer C, et al. The fragile X mental retardation protein binds specifically to its mRNA via a purine quartet motif. EMBO J. 2001;20:4803–4813. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Darnell JC, et al. Fragile X mental retardation protein _targets G quartet mRNAs important for neuronal function. Cell. 2001;107:489–499. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00566-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rozhdestvensky TS, Crain PF, Brosius J. Isolation and posttranscriptional modification analysis of native BC1 RNA from mouse brain. RNA Biol. 2007;4:11–15. doi: 10.4161/rna.4.1.4306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skryabin BV, et al. Neuronal untranslated BC1 RNA: _targeted gene elimination in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:6435–6441. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.18.6435-6441.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Denman RB. Déjà vu all over again: FMRP binds U-rich _target mRNAs. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;310:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown V, et al. Microarray identification of FMRP-associated brain mRNAs and altered mRNA translational profiles in fragile X syndrome. Cell. 2001;107:477–487. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00568-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muddashetty R, et al. Poly(A)-binding protein is associated with neuronal BC1 and BC200 ribonucleoprotein particles. J Mol Biol. 2002;321:433–445. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00655-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.West N, et al. Shared protein components of SINE RNPs. J Mol Biol. 2002;321:423–432. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00542-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Todd PK, Mack KJ, Malter JS. The fragile X mental retardation protein is required for type-I metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent translation of PSD-95. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14374–14378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336265100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grossman AW, Aldridge GM, Weiler IJ, Greenough WT. Local protein synthesis and spine morphogenesis: Fragile X syndrome and beyond. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7151–7155. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1790-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Darnell JC, et al. Kissing complex RNAs mediate interaction between the Fragile-X mental retardation protein KH2 domain and brain polyribosomes. Genes Dev. 2005;19:903–918. doi: 10.1101/gad.1276805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dolzhanskaya N, et al. The fragile X mental retardation protein interacts with U-rich _target RNAs in a yeast-3-hybrid system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;305:434–441. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00766-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson EM, et al. Role of Pur alpha in _targeting mRNA to sites of translation in hippocampal neuronal dendrites. J Neurosci Res. 2006;83:929–943. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gabus C, et al. The fragile X mental retardation protein has nucleic acid chaperone properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:2129–2137. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rozhdestvensky T, Kopylov A, Brosius J, Hüttenhofer A. Neuronal BC1 RNA structure: Evolutionary conversion of a tRNAAla domain into an extended stem-loop structure. RNA. 2001;7:722–730. doi: 10.1017/s1355838201002485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garber K, Smith KT, Reines D, Warren ST. Transcription, translation and fragile X syndrome. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16:270–275. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tiedge H. RNA reigns in neurons. Neuron. 2005;48:13–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mazroui R, et al. Trapping of messenger RNA by Fragile X Mental Retardation protein into cytoplasmic granules induces translation repression. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:3007–3017. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.24.3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ule J, Jensen K, Mele A, Darnell RB. CLIP: A method for identifying protein-RNA interaction sites in living cells. Methods. 2005;37:376–386. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brendel C, et al. Characterization of Staufen 1 ribonucleoprotein complexes. Biochem J. 2004;384:239–246. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.