Abstract

One of the outstanding fundamental questions in cancer cell biology concerns how cells coordinate cellular growth (or macromolecular synthesis) with cell cycle progression and mitosis. Intuitively, rapidly dividing cells must have some control over these processes; otherwise cells would continue to shrink in volume with every passing cycle, similar to the cytoreductive divisions seen in the very early stages of embryogenesis. The problem is easily solved in unicellular organisms, such as yeast, as their growth rates are entirely dependent on nutrient availability. Multicellular organisms such as mammals, however, must have acquired additional levels of control, as nutrient availability is seldom an issue and the organism has a prodigious capacity to store necessary metabolites in the form of glycogen, lipids, and protein. Furthermore, the specific needs and specialized architecture of tissues must constrain growth for growth’s sake; if not, the necessary function of the organ could be lost. While certainly a myriad of mechanisms for preventing this exist via initiating cell death (e.g. apoptosis, autophagy, necrosis), these all depend on some external cue, such as death signals, hypoxia, lack of nutrients or survival signals. However there must also be some cell autonomous method for surveying against inappropriate growth signals (such as oncogenic stress) that occur in a stochastic fashion, possibly as a result of random mutations. The ARF tumor suppressor seems to fulfill that role, as its expression is near undetectable in normal tissues, yet is potently induced by oncogenic stress (such as overexpression of oncogenic Ras or myc). As a result of induced expression of ARF, the tumor suppressor protein p53 is stabilized and promotes cell cycle arrest. Mutations or epigenetic alterations of the INK4a/Arf locus are second only to p53 mutations in cancer cells, and in some cancers, alterations in both Arf and p53 observed, suggesting that these two tumor suppressors act coordinately to prevent unwarranted cell growth and proliferation. The aim of this review is to characterize the current knowledge in the field about both p53-dependent and independent functions of ARF as well as to summarize the present models for how ARF might control rates of cell proliferation and/or macromolecular synthesis. We will discuss potential therapeutic _targets in the ARF pathway, and some preliminary attempts at enhancing or restoring the activity of this important tumor suppressor.

Keywords: ARF, Mdm2, p53, nucleophosmin, nucleolus, ribosome biogenesis

INTRODUCTION

Since its discovery as a product of the alternate reading frame of the mouse INK4a/Arf locus [1], the ARF tumor suppressor has been identified as a key sensor of hyperproliferative signals such as those emanating from the Ras and Myc oncoproteins [2–4]. p16INK4a and ARF are transcribed from separate and unique first exons (over 10 kilobases apart) which splice into two shared exons [1] (Fig. (1)). While INK4a and ARF share considerable homology at the DNA level (nearly 70%), the translated proteins are completely distinct from one another. This is due to the unprecedented splicing utilized by ARF which causes a frame shift (alternate reading frame) in the coding region of exon two (and thus providing the ARF moniker). The INK4a/Arf locus is frequently _targeted for loss of function in diverse human cancers and both p16INK4a and ARF function as tumor suppressors despite a lack of sequence similarity. ARF is a highly basic (predicted pI=11), insoluble protein which exhibits little structure apart from a pair of alpha helices at its amino terminus [5]. Both mouse and human ARF have been widely studied in the decade since their discovery. Although they differ in size (mouse ARF is 19 kDa and human ARF is 14 kDa) and exhibit only 49% sequence identity, the functions of the ARF proteins appear to be conserved in man and mice. ARF is a bona fide tumor suppressor. Ectopic ARF is capable of arresting immortal rodent cell lines as well as transformed human cells [6, 7], a classic and requisite property of tumor suppressors. The ability of ARF to inhibit cell cycle progression in numerous cell types, suggested that ARF had powerful growth-inhibitory functions in the cell and prompted many researchers to study the in vivo ability of ARF to prevent tumorigenesis.

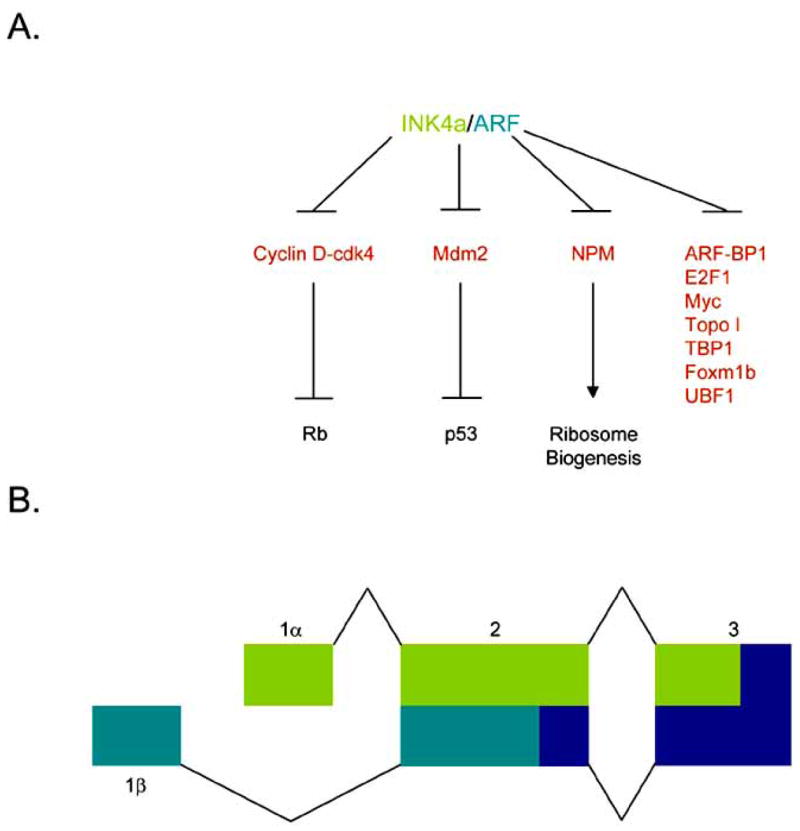

Fig 1. INK4a/Arf locus and effector pathways.

A. INK4a inhibits the activity of cyclin D-cdk4 holoenzymes to keep Rb hypo-phosphorylated and active. ARF blocks the activity of Mdm2 thereby activating p53 as well as inhibiting NPM shuttling activity to prevent ribosome biogenesis. In addition, ARF attenuates the activity of several other proteins although the biological outcomes of these interactions are still under intense study. B. The INK4a/Arf locus. Using an uniquely conserved arrangement of exons, INK4a (Exon 1α, light green) and ARF (Exon 1β, dark green) splice into common 2nd and 3rd exons but in alternate reading frames to produce to distinctive amino acid sequences and structurally unrelated proteins.

LOSS OF ARF IN CANCER

Animal studies have been very valuable in elucidating the function of murine p19ARF as a tumor suppressor. Arf-null mice, generated by specifically _targeting exon 1β, exhibit spontaneous tumor formation as early as 8 weeks of age [3]. Sarcomas and lymphomas are the most common tumors observed in Arf-deficient mice. Tumor development is also accelerated in newborn Arf-null mice treated with carcinogens when compared to wild-type mice [3, 8], demonstrating that ARF protects cells against aberrant cell growth and proliferation caused by increased mutagenesis. Another interesting facet of ARF biology is the observed immortal phenotype of cultured Arf-null mouse endothelial fibroblasts (MEFs). Unlike its wild-type counterparts which senesce after 10–15 passages in vitro, Arf-deficient MEFs are capable of growing infinitum in culture [3]. Moreover, immortal Arf-null MEFs are susceptible to transformation by oncogenic Ras alone, indicating that loss of Arf can be substituted for Myc overexpression in classic cooperating transformation assays with Ras [3]. This finding was further refined through experiments that showed the acute loss of Arf as a major event in Myc-induced cellular immortalization in vivo [9].

Consistent with initial findings in mice, frequent mutation or deletion of the INK4a/Arf in numerous human cancers was discovered. It is difficult, however, to assess the relative importance of p16INK4a and ARF individually since mutation or deletion at the INK4a/Arf locus frequently affects both proteins. Mutation of exon 1β, which would specifically affect only ARF, is a relatively rare event. However, a germline deletion of a region containing exon 1β of p14ARF but leaving the INK4a gene intact was identified in a family prone to melanoma and neural system tumor development [10]. An exon 1β mutation that altered the growth-inhibitory properties and intracellular localization of human p14ARF was observed and characterized in a melanoma patient [11]. Building on these early reports, ARF haploinsufficiency due to a germline mutation in exon 1β was observed in a family of three individuals with melanoma or breast cancer. However, somatic changes at the INK4a/Arf locus discovered in one of the melanoma samples resulted in inactivation of both p14ARF and p16INK4a [12]. Recently, a germline deletion of exon 1β was discovered in two patients from a family predisposed to cutaneous malignant melanoma. A heterozygous germline missense mutation in exon 1β was also found in another individual with melanoma [13]. More commonly, however, exon 2 is the site of mutation, affecting either p16INK4a, ARF, or both proteins. Some of these exon 2 mutations alter ARF localization and affect its regulation of downstream _target proteins [14–16]. Silencing of the Arf gene promoter through hypermethylation is frequently observed in low-grade diffuse astrocytomas [17], oligodendroglial tumors [18, 19], ependymal tumors [19, 20], kidney cancer [21], hepatocellular carcinoma [22], and oral squamous cell carcinomas [23]. Simultaneous methylation of both Arf and INK4a is also a common occurrence in samples from the accelerated phase of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) [24]. In one study, loss of p14ARF expression was observed in 38/50 glioblastomas, with 29 displaying either homozygous deletion or hypermethylation of Arf. While deletion of both p14ARF and p16INK4a was common, Arf was specifically deleted in nine of the samples [25], indicating that ARF alone is often a major _target in human tumor progression (for a complete list of ARF-specific alterations in human cancers, see Table 1).

Table 1.

| Disease | ARF alteration | Occurrence | ARF specificity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| acute lymphoblastic leukemia | deletion | 40% ; 45% | No | [97, 98] |

| adult acute myelogenous leukemia | deletion | 5% | No | [99] |

| adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma | methylation | 6% | ND | [100] |

| anal squamous cell carcinoma | methylation | 25% | ND | [101] |

| anaplastinc meningioma | 1. loss of mRNA expression

2. mutation OR deletion 3. methylation |

71%

67% 50% |

20%

No ND |

[102]

[103] [104] |

| anaplastic oligodendroglioma | methylation OR deletion | 40% | 25% | [105] |

| angiosarcoma | methylation | 26% | 40% | [106] |

| atypical meningioma | 1. loss of mRNA expression

2. deletion OR methylation 3. methylation |

17%

6% 20% |

No

No ND |

[102]

[103] [104] |

| astrocytomas (low grade) | methylation | 10% ; 20% | ND ; 100% | [107, 17] |

| astrocytomas (high grade) | deletion | 21% | No | [108] |

| Barrett’s adenocarcinoma | methylation | 20% | Yes | [109] |

| benign meningioma | 1. loss of mRNA expression

2. methylation |

44%

9% |

67%

N/D |

[102]

[104] |

| bladder cancer | 1. methylation

2. deletion |

56% ; 31%

43% ; 14% |

67% ; N/D

Yes ; No |

[110, 111]

[112, 113] |

| bladder cancer (Schistosoma-associated) | methylation | 19% | 60% | [114] |

| brain metastases | methylation | 33% | ND | [115] |

| breast cancer/melanoma/pancreatic cancer | mutation | familial | No | [116] |

| breast carcinoma | 1. methylation

2. deletion OR methylation |

24% ; 19%

20% |

54% ; 58%

ND |

[117, 118]

[119] |

| cholangiosarcoma | methylation | 25% ; 38% | 62% ; ND | [120, 121] |

| chronic myeloid leukemia | 1. methylation

2. mutation 3. methylation AND mutation 4. methylation OR missense mutation |

40%

23% 17% 47% |

17%

71% 60% 14% |

[24] |

| clear cell sarcoma | deletion or mutation | 14% | No | [122] |

| colon cancer | methylation | 33% ; 22% ; 33% | ND ; ND ; ND | [118, 123, 124] |

| colorectal adenoma | methylation | 32% ; 40% | ND ; ND | [125, 126] |

| colorectal carcinoma | methylation | 28% ; 38% ; 51% | 52% ; 50% ; 70% | [126–128] |

| cutaneous melanoma | deletion | 67% ; 46% | 9% ; No | [129, 130] |

| cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma | 1. mutation

2. methylation 3. mutation OR methylation |

8%

40% 43% |

No

75% ND |

[131] |

| EBV-associated gastric carcinoma | methylation | 100% | No | [132] |

| ependymoma | methylation | 21% ; 28% | 96% ; Yes | [20, 19] |

| epithelial ovarian cancer | mutation, methylation, OR loss of

mRNA expression |

22% | 40% | [133] |

| esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | 1. deletion

2. methylation 3. mutation |

33% ; 14%

15% ; 52% ND ; 19% |

Yes ; ND

No ; 73% ND ; No |

[134, 135] |

| Ewing sarcoma | 1. deletion

2. methylation, deletion, OR mutation |

13%

13% |

No

No |

[136, 137] |

| gall bladder/bile duct carcinomas | methylation | 46% | 50% | [138] |

| gastric cancer | methylation | 24% ; 10% | Yes ; ND | [139, 140] |

| gastrointestinal stromal tumors | deletion OR methylation | 32% | No | [141] |

| glioblastoma | 1. deletion

2. deletion OR methylation |

55%

58% ; 67% |

No

45% ; ND |

[142, 25, 143] |

| glioma | deletion | 41% | No | [144] |

| head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma |

1. methylation

2. mutation 3. methylation, mutation, OR deletion |

19%; 16%

35% 43% |

85% ; ND

6% 16% |

[145, 146]

[147] [146] |

| hepatocellular carcinoma | 1. deletion

2. methylation 3. deletion OR mutation 4. deletion, methylation, OR mutation |

25%

42% 7% 20% |

No

ND No No |

[148]

[22] [149] [150] |

| hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer | methylation | 33% | ND | [151] |

| histiocytic sarcoma | methylation | 70% | 86% | [152] |

| intracranial germ cell tumor | deletion OR mutation | 71% | No | [153] |

| kidney tumors | hypermethylation | 17% ; 18% | 71% ; ND | [21, 154] |

| malignant mesothelioma | deletion | 21% | No | [155] |

| malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors | deletion | 50% ; 46% | No ; No | [156, 157] |

| mantle cell lymphoma | deletion | 19% | No | [158] |

| medulloblastoma | 1. methylation

2. methylation OR deltion |

14%

10% |

ND

33% |

[159, 160] |

| melanoma | 1. deletion

2. mutation |

familial

familial |

Yes ; Yes

Yes ; Yes ; No ; No |

[13, 10]

[11, 13, 161, 162] |

| melanoma/breast cancer | germline mutation | familial | ND | [12] |

| metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma | mutation | 38% | 33% | [163] |

| myxoid/round cell liposarcoma | 1. methylation

2. homozygous deletion 3. mutation |

11%

6% 21% |

ND

ND ND |

[164] |

| nasal adenocarcinoma | 1. deletion

2. methylation |

45%

67% |

No

No |

[165] |

| neurofibromas and neurofibrosarcomas | methylation | 5% | ND | [166] |

| non-Hodgkins lymphoma | deletion OR mutation | 11% | No | [167] |

| non-small cell lung cancer | 1. methylation

2. deletion |

8% ; 8% ; 30%

18% |

ND ; ND ; ND

ND |

[168–170]

[171] |

| oligoastrocytoma | methylation | 39% | ND | [107] |

| oligodendroglial tumors | methylation | 44% ; 41% | 78% ; variable | [19, 18] |

| oligodendroglioma | methylation | 37% ; 21% ; 69% | ND ; Yes ; ND | [172, 173, 107] |

| oral carcinoma | deletion | 22% | No | [174] |

| oral squamous cell carcinoma | 1. methylation

2. deletion 3. mutation 4. deletion OR methylation |

20%

24% ; 30% 9% 53% |

30%

Yes ; ND No 12% |

[175]

[176, 177] [178] [23] |

| osteosarcoma | 1. methylation

2. methylation, deletion, OR mutation |

47%

9% |

93%

No |

[179]

[136] |

| primary central nervous system lymphoma | 1. deletion OR methylation

2. deletion OR mutation |

56% ; 48%

90% |

20% ; 13%

No |

[180, 181]

[182] |

| prostate carcinoma | deletion OR methylation | 13% | No | [183] |

| pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma | methylation | 27% | 69% | [184] |

| renal cell carcinoma | deletion or methylation | 5% | No | [185] |

| salivary gland carcinoma | 1. deletion

2. methylation |

8%

19% |

67%

57% |

[186] |

| small bowel adenocarcinoma | hypermethylation | 9% | ND | [187] |

| sporadic colorectal cancer | methylation | 50% | ND | [151] |

| squamous cell carcinoma | mutation | 14% ; 55% | No ; No | [188, 189] |

| supratentorial primitive

neuroectodermal tumor |

methylation | 50% | ND | [159] |

| T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia | mutation OR deletion | 100% | 3% | [190] |

| transitional cell carcinoma | deletion | 25% | No | [191] |

| ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer | methylation | 50% | ND | [192] |

| urothelial cell carcinoma | homozygous deletion | 22% | No | [193] |

| Wilms’ tumors | methylation | 15% | 83% | [194] |

| xeroderma pigmentosum-associated skin carcinoma | mutation | 29% | No | [195] |

ARF specificity signifies incidences where INK4a status is unaffected by the ARF alteration. ND=Not determined.

NUCLEOLAR LOCALIZATION

ARF is predominantly localized to the nucleolus [26, 27], a dynamic, membrane-less, subnuclear organelle which controls ribosome biogenesis [28] (Fig. (2A)). Within the nucleolus, ARF resides in the granular region, which contains maturing ribosomes. During mitosis, the nucleolus disintegrates causing nucleolar proteins to disperse throughout the nucleoplasm [29]. Interestingly, nucleolar dissociation is linked with an increase in p53 [30], suggesting that the nucleolus may be an important structure involved in regulating the p53 pathway. Nucleolar breakdown due to mitosis or stress may allow transient ARF activity in the nucleoplasm [31, 32], however non-nucleolar ARF exhibits decreased stability [33]. Importantly, the last two years have been marked with increased understanding of the role of the nucleolus in sensing both environmental and oncogenic stress within the cell [30, 28].

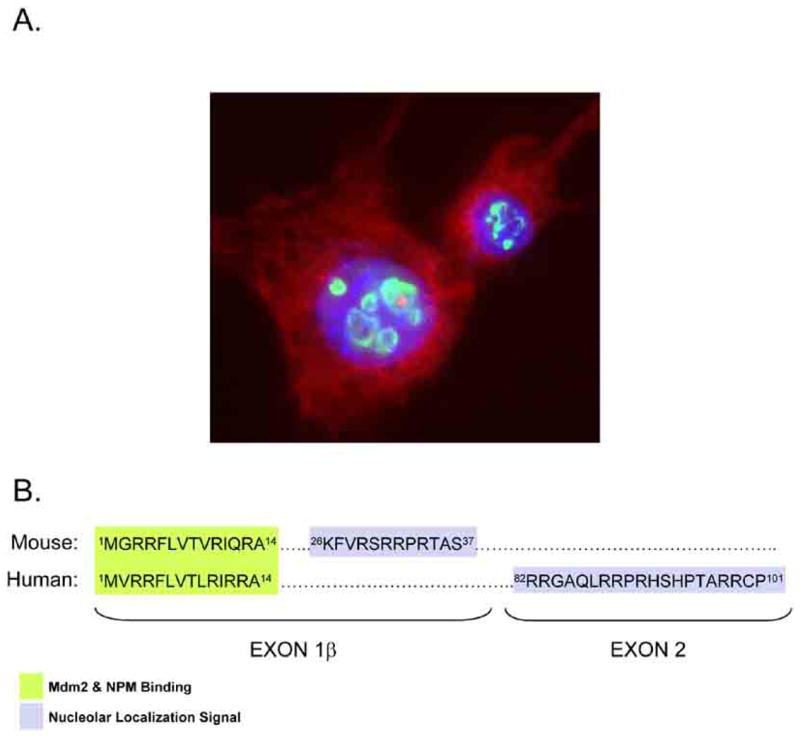

Fig 2. ARF Nucleolar Localization.

A. Wild type mouse embryonic fibroblasts show ARF (green) localized to the subnuclear organelle, the nucleolus. Nuclear DNA (blue) and cytoplasmic actin (red) are also shown. B. Alignment of Exon1β and Exon 2 is shown for mouse and human ARF with Mdm2 and NPM binding sites (green) and nucleolar localization signals (blue) shown.

Interestingly, the amino acid residues responsible for the nucleolar localization of mouse p19ARF and human p14ARF are somewhat different [34]. While the nucleolus is not partitioned from the nucleoplasm by a membrane, entry into this organelle is not thought to be a passive event. Rather, proteins that reside within the nucleolus often contain arginine and lysine rich domains reminiscent of nuclear localization signals that somehow _target them to the nucleolus. However, these positively charged tracts are not obligatory for protein nucleolar localization. In fact, many proteins utilize protein-protein and protein-RNA interactions to “hitch” a ride into the nucleolus. Both mouse and human ARF proteins contain arginine-rich sequences (in fact, both proteins are nearly 25% arginine), albeit in different moieties along ARF’s amino acid sequence. In particular, residues 26-37 are critical for the nucleolar localization murine p19ARF [27] (Fig. (2B)). In humans, amino acids 2-14 and 82-101 of p14ARF are important for its nucleolar localization [34, 15, 16] (Fig. (2B)). Of note, deletion of the nucleolar localization signal within either mouse or human ARF results in a loss of ARF’s ability to promote cell cycle arrest, revealing that the biological function of ARF might be intimately tied to its ability to properly localize to the nucleolus. However, this simplistic model is complicated by the observation that the regions of ARF that are important for its nucleolar localization also mediate most of the interactions that are critical for its functions. Thus, the critical determinant of functional ARF resides in its ability to interact with numerous oncoproteins.

ACTIVATION OF P53

ARF is most commonly known for its well-characterized activation of the p53 pathway (Fig. (1A)). The p53 gene is the most common _target of mutations which inactivate protein function or compromise its expression in human cancers. In fact, p53 is disrupted in greater than 50% of all human cancers. In response to cellular stress, p53 is activated to induce cell cycle arrest or trigger apoptosis depending on the setting. These stress cues include DNA damage, nucleotide depletion, viral infection, heat shock, and oncogenic stimuli. The crucial negative regulator of p53 is the E3 ubiquitin ligase, Mdm2 (Hdm2 in humans). Mdm2 binds to p53 and promotes its nuclear export and degradation through post-translational ubiquitin modification [35]. In the absence of Mdm2, p53 activity is unchecked, resulting in unrestrained apoptosis in cells and mice [36, 37]. Conversely, coinciding loss of p53 and Mdm2 rescues the apoptotic phenotype and mimics the loss of p53 alone [36–38].

In response to oncogenic signals such as those emanating from Ras and Myc, ARF is up-regulated and accumulates in the nucleolus. ARF interacts with Mdm2, preventing its nucleocytoplasmic shuttling and drawing it into the nucleolus [39, 40, 27]. In this manner, Mdm2 is sequestered by nucleolar ARF molecules. This liberates p53 in the nucleoplasm where it is free to activate numerous downstream transcriptional regimens. Both Mdm2 and ARF are transcriptional _targets of p53, with Mdm2 expression increased and ARF repressed in a negative feedback loop [41]. Moreover, the main consequences of p53 activation, cell cycle arrest or apoptosis, are mediated by p53 _target genes such as p21CIP1 and PUMA, respectively. Recent reports have indicated that the tumor suppressive activities of p53 are mediated by oncogenic activation of ARF and not the DNA damage response [42, 43], suggesting that ARF is the key player in relaying cellular cues to the p53 tumor suppressor.

Interestingly, the residues in ARF (both mouse and human) that are critical for binding to Mdm2 also regulate ARF’s nucleolar localization and cell cycle arrest [16, 34]. The amino-terminal 37 residues of p19ARF (contained within exon 1β) are sufficient for all of its known properties including its binding to Mdm2 and localization to the nucleolus [27, 34]. Mdm2 also contributes to its nucleolar co-localization with ARF through a cryptic nucleolar localization signal which is revealed upon binding to ARF [44]. The notion that nucleolar sequestration of Mdm2 by ARF is necessary for its activation of p53 has been challenged by reports showing that ARF-mediated regulation of p53 can occur independent of Mdm2 nucleolar re-localization [45, 46]. Observations of ARF function in the nucleoplasm, particularly in regards to its interaction with Mdm2, opens a new set of possibilities as to how ARF can suppress growth under diverse circumstances. Thus, despite its steady-state localization to the nucleolus, ARF may exhibit growth-inhibitory processes that are independent of its ability to sequester Mdm2 in the nucleolus. However, nucleolar sequestration of Mdm2 by PML occurs in response to DNA damage [47], suggesting that Mdm2 re-localization to nucleoli, while not absolutely necessary, may be a common feature in different pathways of p53 activation.

MDM2 INHIBITORS

Through its inhibition of Mdm2 in response to oncogenic stimulation, ARF plays a key role in p53 pathway activation. In cells where ARF expression or function is lost through mutation or deletion, the aberrant activation of oncogenes does not induce a typical p53 response, but rather results in cellular transformation [3, 48]. Mdm2 gene amplification, which occurs in tumors expressing wild-type p53 [49], is capable of overriding the suppressive effects of ARF [50]. Thus, Mdm2 represents a promising _target for p53-positive tumors. Direct _targeting of Mdm2 with pharmacological inhibitors has the potential to increase p53 protein levels and activity. Furthermore, the use of Mdm2 inhibitors would bypass the normal requirement for ARF in p53’s response to oncogenic stimuli, making it an effective therapy in tumors lacking functional ARF.

Several attempts have been made to identify molecules that _target the p53-inhibitory activities of Mdm2 with a few promising candidates emerging. The nutlins are a class of Mdm2 inhibitors, identified in a synthetic chemical library screen, which occupy the hydrophobic p53-binding pocket of Mdm2. Nutlins inhibit the interaction between p53 and Mdm2 in a dose-dependent manner in vitro. In cancer cell lines that retain wild-type p53, nutlins inhibit cell cycle progression and induce p53 expression and subsequent apoptosis. Nutlin-3 inhibited growth of tumor xenografts in nude mice without any reported side effects over a three week treatment regimen [51, 52]. Further, in non-transformed fibroblasts and primary human mammary epithelial cells, nutlins produce a growth-inhibitory response without eliciting apoptotic toxicity [52, 53]. The HLI98 class of Hdm2 inhibitors was identified from a screen for small molecules which inhibited auto-ubiquitination of Hdm2. Dose-dependent inhibition of p53 ubiquitination and an increase in p53 protein levels and transcription were observed with HLI98. Additionally, HLI98 molecules induced apoptosis and inhibited colony formation. Unlike nutlins, HLI98 molecules do not inhibit the interaction of Hdm2 with p53 [54], but rather the E3 ligase activity of Mdm2. However, HLI98 molecules exhibit limited specificity. Thus, further refinement is needed to improve the feasibility of specifically _targeting Hdm2 ubiquitin ligase activity.

Problems surrounding the therapeutic use of Mdm2/Hdm2 inhibitors include potential toxicity in normal tissues due to uncontrollable p53 activity. Moreover, successful inhibition of Mdm2 may well lead to stabilization of p53 but may not elicit a therapeutic response due to other possible mutations in downstream components of the p53 signaling pathway. It seems likely that prolonged treatment with Mdm2 inhibitors may elicit unfavorable responses given a recent report demonstrating severe pathologies in Mdm2-null mice conditionally expressing p53 [53]. Deletion of Mdm2 is embryonic lethal in mice expressing wild-type p53, however p53/Mdm2 double-null mice are viable, indicating that unrestrained p53 activity is fatal during development [36, 37]. To overcome this hurdle, Ringhausen et. al. used a previously described p53 knock-in mouse model, in which p53 expression was induced by tamoxifen [55], in the context of an Mdm2-null background [53]. Tamoxifen administration induced apoptosis and atrophy in radiosensitive tissues and tamoxifen-treated mice died within a week [53]. Therefore, despite great interest in the development of Mdm2 inhibitors, unrestrained p53 activity is a potentially dangerous consequence.

P53-INDEPENDENT _targetS

Mounting evidence suggests that ARF has a second, p53-independent, function [56, 57]. The most convincing data presented to date involved the use of mouse genetics to confirm that p53 and ARF could contribute independently to suppressing tumorigenesis. Mice lacking p53 or Arf are highly tumor-prone with mean latencies for survival of 19 and 32 weeks, respectively [56]. In mice lacking p53, T-cell lymphomas predominate (~70%), with the remainder being sarcomas. In contrast, Arf-null mice develop far fewer cases of lymphoma (~25%) and primarily develop poorly differentiated sarcomas (~50%), with the remainder appearing as rare carcinomas and gliomas [8]. Surprisingly, mice deficient for both p53 and Arf showed a wider range of tumor types than animals lacking either gene alone, and many developed multiple primary tumors without affecting the mean latency of survival (~16 weeks) [56]. To date, more than half of the p53/Arf-null animals have developed wide-ranging multiple-type tumors strongly demonstrating that ARF has additional p53-independent functions. Cells devoid of both p53 and Arf grow at a faster rate and are more resistant to apoptotic signals than cells lacking only p53 or Arf [9], demonstrating a cooperative effect of p53 and Arf loss on cell proliferation. This also implies that ARF may functionally interact with proteins other than p53 and Mdm2 to prevent cell growth (see below). While p53-null mouse embryo fibroblasts are fairly resistant to ARF overexpression, cells deficient for both p53 and Mdm2 are sensitive to ARF-induced growth arrest. This indicates that ARF can act as a bona fide tumor suppressor independent of p53 and that Mdm2 can antagonize this effect.

Additionally, in mouse eye development, proper hyaloid vascular regression is dependent upon ARF, but not p53. Arf-null mice exhibited accumulation of a retrolental mass, lens degeneration, and lens capsule disruption, symptoms characteristic of the human eye disorder persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous [57]. Induction of p53-independent apoptosis by ARF in colon cancer cells occurs via degradation of CtBP [58]. ARF has also been reported to regulate the transcriptional activities of MYC and E2F1 through direct binding to Myc, E2F1 and DP1, respectively. Regulation of these transcription factors by ARF appears to be independent of p53 or Mdm2 [59, 60]. To date, numerous binding partners for ARF have been discovered [61–68]. Many of these have been shown to regulate ARF function in p53-dependent growth inhibition. For others, the potentially diverse functional consequences of their interactions with ARF are still being characterized. One recently identified interactor, ARF-BP1/Mule, is a ubiquitin ligase which is inhibited by ARF. Inactivation of ARF-BP1 inhibits growth through both p53-dependent and p53-independent mechanisms making ARF-BP1 a promising potential therapeutic _target for future investigation [61].

The addition of a small ubiquitin-like SUMO molecule, in a process known as sumoylation, is a post-translational modification that can alter stability and function of the _target protein. Recent evidence has shown that ARF promotes the p53-independent sumoylation of numerous proteins, including Mdm2 [69, 70]. Werner’s helicase is sumoylated by ARF, resulting in its redistribution from the nucleolus to other sites within the nucleoplasm [71]. Binding of p14ARF to a SUMO-conjugating enzyme facilitates sumoylation of several proteins including Hdm2, E2F-1, and HIF-1α. Interestingly, point mutations in p14ARF associated with melanoma altered the ability of ARF to promote sumoylation of Hdm2 or E2F-1 [72], implying that the sumoylation activity of ARF may be a critical component of both its p53-dependent and independent tumor suppressive properties. As such, novel compounds aimed at promoting or mimicking sumoylation of ARF _targets may provide a unique mechanism for restoring ARF activity to tumor cells lacking functional ARF.

THE ARF-NPM INTERACTION

Some of the most exciting ARF work in recent years involved the independent discovery of NPM as a nucleolar ARF binding partner by several groups [73, 74, 50, 75]. Nucleophosmin (NPM) is implicated in cancer biology, with both oncogenic and tumor suppressive functions attributed to this relatively abundant protein [76, 77]. Nucleophosmin undergoes CRM1-dependent nucleocytoplasmic shuttling and regulates the nuclear export of ribosomal protein L5 in order to promote ribosome nuclear export [78, 50, 79]. In fact, one p53-independent function of ARF is to inhibit the transport of ribosomal RNAs to the cytosol by sequestering NPM in the nucleolus [79, 50], reiterating the notion that NPM shuttling is a crucial event in cell cycle progression. Mutations that confer additional nuclear export signals onto NPM, such that NPM rapidly shuttles to the cytoplasm, are associated with acute myeoloid leukaemia (AML) [80]. Additionally, chromosomal translocations involving NPM are common in hematological malignancies, while NPM overexpression is observed in diverse tumors [77]. The importance of NPM in maintaining growth and proliferation is underscored by the embryonic lethality observed in Npm1-null mice [76, 81].

NPM interacts with ARF in an association that has apparent functional consequences for both proteins. NPM maintains the stability and nucleolar localization of ARF [81, 82, 75] and a cytoplasmic NPM mutant associated with AML redistributes ARF to the cytoplasm and reduces its stability [83, 82], suggesting that while ARF can _target the function of NPM, ARF itself can be influenced by NPM oncoproteins [83, 82, 84, 77]. While ARF is stabilized by its interaction with NPM, adenoviral expression of ARF decreased NPM protein levels [73], although other studies have shown that overall levels of NPM remain largely unchanged in cells despite large differences in ARF expression [74, 50]. The interaction of ARF with NPM is mediated by the amino terminus of p14ARF or p19ARF proteins [74, 50, 73]. Notably, this is the same region required for the formation of ARF-Mdm2 complexes. Indeed, ARF prefers to bind to Mdm2 under conditions of equal molar Mdm2 and NPM, arguing that p53-independent functions of ARF might be sensitive to Mdm2 inhibition [50]. This would provide an additional mechanism by which _targeted therapeutics against Mdm2 might also reinstate p53-independent functions of ARF.

ROLE OF ARF IN RIBOSOME BIOGENESIS

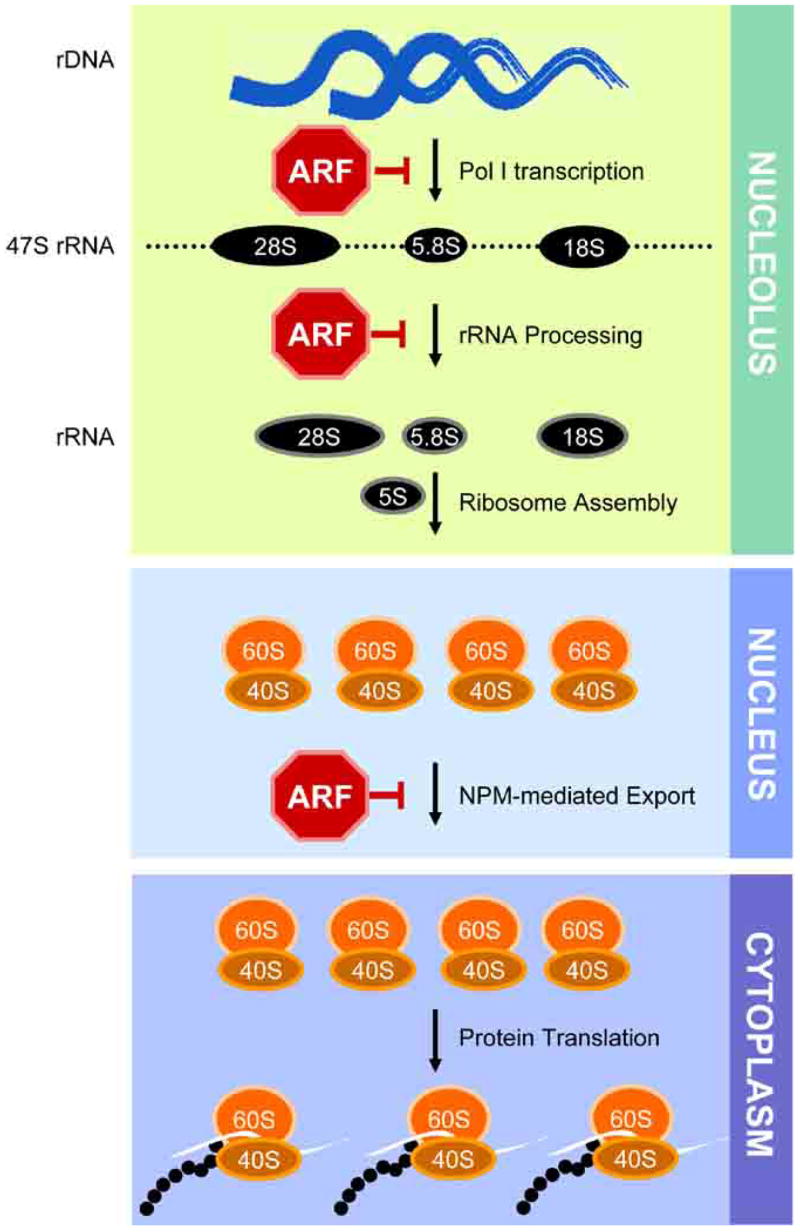

NPM presents itself as a more teleological _target of ARF tumor suppression, one that allows nucleolar ARF to interfere with proper ribosome assembly and export. Recent hypotheses place the nucleolus as a relaying center for the interpretation of growth and proliferation signals. In this sense, ribosome biogenesis is a critical step in both the regulation of mRNA translation and cell cycle progression with alterations in nucleolar function resulting in huge gains in protein synthesis and eventually, cell growth [28, 30]. How ARF might be involved in these dynamic processes has been debated in recent years. Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments identified p14ARF at the promoter of rDNA loci and further established a functional interaction between ARF and UBF, a potent inducer of rDNA transcription [85]. Additionally, ARF may act as a checkpoint protein in ribosome biogenesis via inhibition of ribosomal RNA processing [86], resulting in fewer mature cytosolic ribosomes. This potential role seems likely given the localization of ARF in the nucleolus and its ability to inactivate NPM, a key player in ribosome biogenesis. This is further supported by the observation that either ARF overexpression or mutation of the NPM nuclear export signal increased nuclear retention of 5S rRNA [79]. One might conclude that ARF could perform all three functions to ensure that ribosome biogenesis was completely inhibited (transcription, processing and export) (Fig. (3)) during conditions where ARF is hindering the oncogenic signals presented by Ras and Myc. Loss of Arf or overexpression of NPM could increase ribosome biogenesis and accelerate tumorigenesis through tremendous gains in protein synthesis. Thus, the involvement of ARF in the regulation of translation provides a unique opportunity and potential blueprint as to how small molecule inhibitors against NPM might be used to _target the ribosome synthetic machinery to prevent tumorigenesis originating from nucleolar dysfunction.

Fig 3. ARF and Ribosome Biogenesis.

The processes of ribosome biogenesis from transcription of rDNA loci to translating polysomes with the known steps sensitive to ARF inhibition are shown.

SYNTHETIC ARF PEPTIDES

Recently, peptide delivery has begun to show promise as a legitimate therapeutic strategy, with several studies showing beneficial anti-cancer activity of peptides in vivo. Injection of a peptide from the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor inhibited the growth and invasiveness of renal tumor implants in nude mice [87]. A peptide containing the D-isomer of a p53 C-terminal fragment was able to activate endogenous p53, inhibit tumor growth, and prolong survival of tumor-bearing mice [88]. Shepherdin, a peptide from survivin that inhibits Hsp90, inhibited tumor growth when injected into mice bearing prostate cancer xenografts [89].

Several studies have indicated that all of the known biological functions of ARF are mediated by the N-terminal amino acids 2-14. Deletion of these residues from mouse and human ARF blocks its recruitment of Mdm2 to the nucleolus, impairs its binding to NPM, and prevents its ability inhibit cell growth and proliferation in both p53 wild-type and p53/Mdm2-null cells [56, 34, 16, 74, 50]. ARFΔ2-14 (lacking residues 2-14) is unable to bind to 5.8S rRNA and subsequently unable to inhibit rRNA processing and proliferation of p53/Mdm2/Arf-null MEFs [86]. Residues 2-14 of ARF are sufficient for binding Mdm2 and NPM [34, 50] and are required for the sumoylation of ARF _target proteins [70], suggesting that this short stretch of conserved amino acids (from mice and man) has considerable potential for use in reconstituting ARF function in vivo.

Therapeutic delivery of a small ARF peptide, such as ARF (amino acids 2-14) may mimic the growth-inhibitory effects of full-length ARF expression. In cancers where Mdm2 is overexpressed or where ARF expression is lost through mutation, deletion, or hypermethylation of the Arf locus, introduction of a synthetic ARF peptide might restore its regulatory effects on Mdm2. Inhibition of Mdm2 by synthetic ARF peptides may restore p53 activity in these tumors or, in tumors lacking p53, inhibit ribosome biogenesis (through NPM inactivation) and subsequent cell growth. In fact, expression of the peptide p14ARF (amino acids 1-20) induced p53 expression and prevented its ubiquitination [90], demonstrating the huge potential of this strategy.

It remains to be determined whether intra-tumoral delivery of ARF peptides is feasible. The unusual amino acid sequence and relative lack of structural information about ARF makes it a challenging candidate as a peptide-based therapeutic. Attachment of a Protein Transduction Domain (PTD) may facilitate delivery of an ARF peptide into the cell, but may also alter its localization. A basic PTD, like that of the HIV TAT protein, is less likely to interfere with the nucleolar localization of an ARF peptide. Additionally, isomers of ARF peptides may enhance its stability and potency without affecting its native nucleolar localization. However, specific _targeting of ARF is also a concern, as unregulated p53 activity would be toxic to both tumor and normal cells. Proof-of-principle remains to be established regarding the possible efficacy of ARF peptides as therapeutic anti-cancer agents, but ongoing mutagenesis studies of ARF residues 2-14 could reduce the number of critical amino acids required for ARF function. This would essentially provide chemists with the opportunity to mimic short ARF peptides with the goal of generating chemical compounds that would be capable of inhibiting Mdm2 and NPM function in a manner analogous to ARF.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

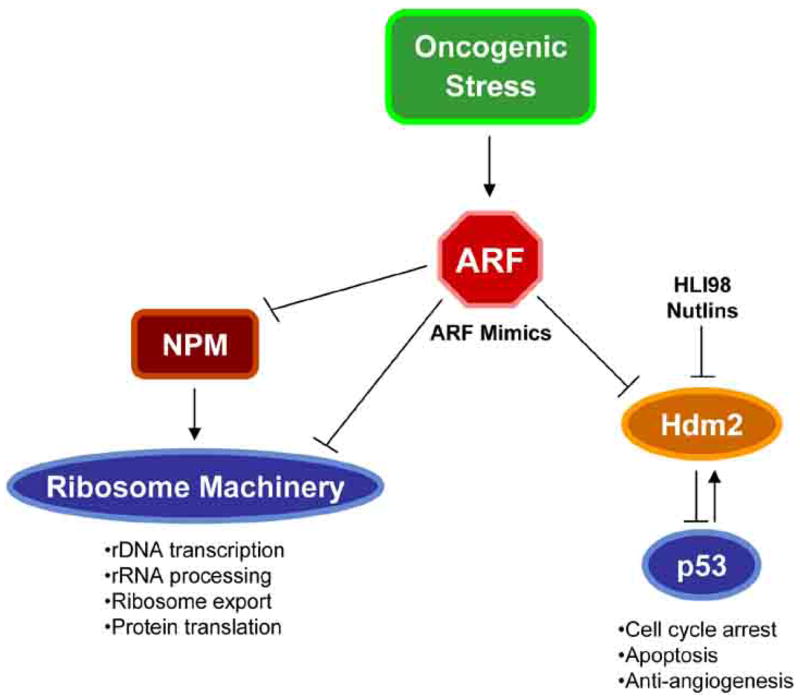

As a nucleolar tumor suppressor, ARF is positioned to sense and regulate growth in the cell (Fig. (4)). In response to hyper-growth or hyper-proliferative signals, ARF protein levels increase in the nucleolus leading to cell cycle arrest. Current interest in ARF biology for pharmaceutical companies certainly lies within the selective inhibition of Mdm2 molecules, as numerous compounds are under pre-clinical and clinical investigation for their efficacy in this regards. While these compounds, from a structural standpoint, may not be true ARF mimics, they could be viewed as functional ARF substitutes with their activities serving to potentiate a p53 response in tumor cells. The major drawback to this approach is in its inherent reliance on an intact p53 gene. However, genetic evidence suggests that p53-indpendent _targets of Hdm2 may also contribute to the oncogenic capabilities of Hdm2 [91, 92]. If this holds true, then Hdm2 inhibitors may have profound effects in tumors regardless of their p53 status.

Fig 4. ARF as a therapeutic agent.

ARF mimics could be used to combat tumorigenesis through inhibition of cellular growth by arresting ribosome biogenesis or blocking cellular proliferation through activation of p53.

Given its nucleolar localization, it is not surprising that ARF can inhibit numerous steps in ribosome biogenesis. In fact, one could argue that this might be ARF’s teleological role in the cell: maintaining ribosome homeostasis, although definitive experiments in this regard are currently lacking. While it is easy to envisage the effect that inhibiting ribosome production would have on the growth of tumor cells, the side effects of inhibiting these processes in normal cells might be too great to utilize this approach clinically. However, new trials with known inhibitors of ribosome production could reverse this pessimistic view. Rapamycin and its chemical analogues are currently in various phases of clinical trials based largely on their ability to inhibit protein synthesis signaling pathways mediated by mTOR [93]. Inhibition of mTOR selectively inhibits both CAP-dependent and TOP-dependent translation as well as RNA polymerase I rDNA transcription, effectively stopping ribosome production and protein translation [94, 95]. In fact, in some inherited cancer pre-disposition syndromes normal cells are unaffected by rapamycin while tumor cell growth and proliferation is halted [96], suggesting that tumor cells might be far more sensitive to translation inhibition. Viewed another way, tumor cells might simply require greater protein production in order to maintain their proliferative capacity, making them super-sensitive to slight reductions in ribosome output. Under these conditions, ARF mimics (either peptides or small molecules) or ribosome production inhibitors (transcription, processing or export) might be potent inhibitors of tumorigenesis, again regardless of p53 status, without inadvertently affecting normal tissues. Thus, restoring ARF function in tumor cells to activate both p53-dependent and -independent pathways, some of which are only beginning to be elucidated, would provide a formidable block to tumor growth.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the other members of the Weber lab for their comments and discussion about the manuscript. A.J.S. is supported by NIH training grant (T32 CA11327501). L.B.M. and A.J.A. are supported by training grants from Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Research Program (W81XWH-04-0909) and Breast Cancer Research Program (W81XWH-04-1-0394), respectively. J.D.W. is a Pew Scholar and is a recipient of grants in aid from the NIH (RO1 GM066032) and Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation.

References

- 1.Quelley DE, Zindy F, Ashmun RA, Sherr CJ. Cell. 1995;83:993. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zindy F, Eischen CM, Randle DH, Kamijo T, Cleveland JL, Sherr CJ, Roussel MF. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2424. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.15.2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamijo T, Zindy F, Roussel MF, Quelle DE, Downing JR, Ashmun RA, Grosveld G, Sherr CJ. Cell. 1997;91:649. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groth A, Weber JD, Willumsen BM, Sherr CJ, Roussel MF. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003417200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiGiammarino EL, Filippov I, Weber JD, Bothner B, Kriwacki RW. Biochemistry. 2001;40:2379. doi: 10.1021/bi0024005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liggett WH, Jr, Sewell DA, Rocco J, Ahrendt SA, Koch W, Sidransky D. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quelle DE, Cheng M, Ashmun RA, Sherr CJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamijo T, Bodner S, van de Kamp E, Randle DH, Sherr CJ. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eischen CM, Weber JD, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ, Cleveland JL. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2658. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.20.2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Randerson-Moor JA, Harland M, Williams S, Cuthbert-Heavens D, Sheridan E, Aveyard J, Sibley K, Whitaker L, Knowles M, Bishop JN, Bishop DT. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:55. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rizos H, Puig S, Badenas C, Malvehy J, Darmanian AP, Jimenez L, Mila M, Kefford RF. Oncogene. 2001;20:5543. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hewitt C, Lee Wu C, Evans G, Howell A, Elles RG, Jordan R, Sloan P, Read AP, Thakker N. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1273. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.11.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laud K, Marian C, Avril MF, Barrois M, Chompret A, Goldstein AM, Tucker MA, Clark PA, Peters G, Chaudru V, Demenais F, Spatz A, Smith MW, Lenoir GM, Bressac-de Paillerets B. J Med Genet. 2006;43:39. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.033498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rizos H, Darmanian AP, Holland EA, Mann GJ, Kefford RF. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:41424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105299200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Xiong Y. Mol Cell. 1999;3:579. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80351-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lohrum MA, Ashcroft M, Kubbutat MH, Vousden KH. Curr Biol. 2000;10:539. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00472-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watanabe T, Katayama Y, Yoshino A, Komine C, Yokoyama T. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:4884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolter M, Reifenberger J, Blaschke B, Ichimura K, Schmidt EE, Collins VP, Reifenberger G. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2001;60:1170. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.12.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alonso ME, Bello MJ, Gonzalez-Gomez P, Arjona D, Lomas J, de Campos JM, Isla A, Sarasa JL, Rey JA. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2003;144:134. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(02)00928-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rousseau E, Ruchoux MM, Scaravilli F, Chapon F, Vinchon M, De Smet C, Godfraind C, Vikkula M. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2003;29:574. doi: 10.1046/j.0305-1846.2003.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dulaimi E, Ibanez de Caceres I, Uzzo RG, Al-Saleem T, Greenberg RE, Polascik TJ, Babb JS, Grizzle WE, Cairns P. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:3972. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anzola M, Cuevas N, Lopez-Martinez M, Saiz A, Burgos JJ, Martinez de Pancorboa M. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:19. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shintani S, Nakahara Y, Mihara M, Ueyama Y, Matsumura T. Oral Oncol. 2001;37:498. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00142-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagy E, Beck Z, Kiss A, Csoma E, Telek B, Konya J, Olah E, Rak K, Toth FD. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:2298. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(03)00552-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamura M, Watanabe T, Klangby U, Asker C, Wiman K, Yonekawa Y, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H. Brain Pathol. 2001;11:159. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2001.tb00388.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pomerantz J, Schreiber-Agus N, Liegeois NJ, Silverman A, Alland L, Chin L, Potes J, Chen K, Orlow I, Lee HW, Cordon-Cardo C, DePinho RA. Cell. 1998;92:713. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81400-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weber JD, Taylor LJ, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ, Bar-Sagi D. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:20. doi: 10.1038/8991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maggi LB, Jr, Weber JD. Cancer Invest. 2005;23:599. doi: 10.1080/07357900500283085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carmo-Fonseca M, Mendes-Soares L, Campos I. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:E107. doi: 10.1038/35014078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rubbi CP, Milner J. EMBO J. 2003;22:6068. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.David-Pfeuty T, Nouvian-Dooghe Y. Oncogene. 2002;21:6779. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee C, Smith BA, Bandyopadhyay K, Gjerset RA. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9834. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodway H, Llanos S, Rowe J, Peters G. Oncogene. 2004;23:6186. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weber JD, Kuo ML, Bothner B, DiGiammarino EL, Kriwacki RW, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2517. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.7.2517-2528.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roth J, Dobbelstein M, Freedman DA, Shenk T, Levine AJ. EMBO J. 1998;17:554. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montes de Oca Luna R, Wagner DS, Lozano G. Nature. 1995;378:203. doi: 10.1038/378203a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones SN, Roe AE, Donehower LA, Bradley A. Nature. 1995;378:206. doi: 10.1038/378206a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McDonnell TJ, Montes de Oca Luna R, Cho S, Amelse LL, Chavez-Reyes A, Lozano G. J Pathol. 1999;188:322. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199907)188:3<322::AID-PATH372>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okuda M, Horn HF, Tarapore P, Tokuyama Y, Smulian AG, Chan PK, Knudsen ES, Hofmann IA, Snyder JD, Bove KE, Fukasawa K. Cell. 2000;103:127. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tao W, Levine AJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stott FJ, Bates S, James MC, McConnell BB, Starborg M, Brookes S, Palmero I, Ryan K, Hara E, Vousden KH, Peters G. EMBO J. 1998;17:5001. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.17.5001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Efeyan A, Garcia-Cao I, Herranz D, Velasco-Miguel S, Serrano M. Nature. 2006;443:159. doi: 10.1038/443159a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Christophorou MA, Ringshausen I, Finch AJ, Swigart LB, Evan GI. Nature. 2006;443:214. doi: 10.1038/nature05077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lohrum MA, Ashcroft M, Kubbutat MH, Vousden KH. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:179. doi: 10.1038/35004057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Llanos S, Clark PA, Rowe J, Peters G. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:445. doi: 10.1038/35074506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Korgaonkar C, Zhao L, Modestou M, Quelle DE. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:196. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.1.196-206.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bernardi R, Scaglioni PP, Bergmann S, Horn HF, Vousden KH, Pandolfi PP. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:665. doi: 10.1038/ncb1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Palmero I, Pantoja C, Serrano M. Nature. 1998;395:125. doi: 10.1038/25870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Momand J, Jung D, Wilczynski S, Niland J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:3453. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.15.3453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brady SN, Yu Y, Maggi LB, Jr, Weber JD. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9327. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9327-9338.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tovar C, Rosinski J, Filipovic Z, Higgins B, Kolinsky K, Hilton H, Zhao X, Vu BT, Qing W, Packman K, Myklebost O, Heimbrook DC, Vassilev LT. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507493103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vassilev LT, Vu BT, Graves B, Carvajal D, Podlaski F, Filipovic Z, Kong N, Kammlott U, Lukacs C, Klein C, Fotouhi N, Liu EA. Science. 2004;303:844. doi: 10.1126/science.1092472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ringshausen I, O'Shea CC, Finch A, Swigart LB, Evan GI. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:501. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang Y, Ludwig RL, Jensen JP, Pierre SA, Medaglia MV, Davydov IV, Safiran YJ, Oberoi P, Kenten JH, Phillips AC, Weissman AM, Vousden KH. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:547. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Christophorou MA, Martin-Zanca D, Soucek L, Lawlor ER, Brown-Swigart L, Verschuren EW, Evan GI. Nat Genet. 2005;37:718. doi: 10.1038/ng1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weber JD, Jeffers JR, Rehg JE, Randle DH, Lozano G, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ, Zambetti GP. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2358. doi: 10.1101/gad.827300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McKeller RN, Fowler JL, Cunningham JJ, Warner N, Smeyne RJ, Zindy F, Skapek SX. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052484199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Paliwal S, Pande S, Kovi RC, Sharpless NE, Bardeesy N, Grossman SR. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2360. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2360-2372.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Datta A, Nag A, Pan W, Hay N, Gartel AL, Colamonici O, Mori Y, Raychaudhuri P. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:36698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312305200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Datta A, Sen J, Hagen J, Korgaonkar CK, Caffrey M, Quelle DE, Hughes DE, Ackerson TJ, Costa RH, Raychaudhuri P. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:8024. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.18.8024-8036.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen D, Kon N, Li M, Zhang W, Qin J, Gu W. Cell. 2005;121:1071. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rizos H, Diefenbach E, Badhwar P, Woodruff S, Becker TM, Rooney RJ, Kefford RF. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4981. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210978200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tompkins V, Hagen J, Zediak VP, Quelle DE. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tompkins VS, Hagen J, Frazier AA, Lushnikova T, Fitzgerald MP, di Tommaso A, Ladeveze V, Domann FE, Eischen CM, Quelle DE. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:1322. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609612200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pollice A, Nasti V, Ronca R, Vivo M, Lo Iacono M, Calogero R, Calabro V, La Mantia G. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:6345. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310957200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhao L, Samuels T, Winckler S, Korgaonkar C, Tompkins V, Horne MC, Quelle DE. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jackson MW, Lindstrom MS, Berberich SJ. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:25336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010685200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hasan MK, Yaguchi T, Sugihara T, Kumar PK, Taira K, Reddel RR, Kaul SC, Wadhwa R. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:37765. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204177200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tago K, Chiocca S, Sherr CJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:7689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502978102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xirodimas DP, Chisholm J, Desterro JM, Lane DP, Hay RT. FEBS Lett. 2002;528:2071. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Woods YL, Xirodimas DP, Prescott AR, Sparks A, Lane DP, Saville MK. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:50157. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405414200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rizos H, Woodruff S, Kefford RF. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:597. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.4.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Itahana K, Bhat KP, Jin A, Itahana Y, Hawke D, Kobayashi R, Zhang Y. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1151. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00431-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bertwistle D, Sugimoto M, Sherr CJ. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:985. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.985-996.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Korgaonkar C, Hagen J, Tompkins V, Frazier AA, Allamargot C, Quelle FW, Quelle DE. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1258. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.4.1258-1271.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Grisendi S, Bernardi R, Rossi M, Cheng K, Khandker L, Manova K, Pandolfi PP. Nature. 2005;437:147. doi: 10.1038/nature03915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Grisendi S, Mecucci C, Falini B, Pandolfi PP. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:493. doi: 10.1038/nrc1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Borer RA, Lehner CF, Eppenberger HM, Nigg EA. Cell. 1989;56:379. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yu Y, Maggi LB, Jr, Brady SN, Apicelli AJ, Dai MS, Lu H, Weber JD. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3798. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.10.3798-3809.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Falini B, Mecucci C, Tiacci E, Alcalay M, Rosati R, Pasqualucci L, La Starza R, Diverio D, Colombo E, Santucci A, Bigerna B, Pacini R, Pucciarini A, Liso A, Vignetti M, Fazi P, Meani N, Pettirossi V, Saglio G, Mandelli F, Lo-Coco F, Pelicci PG, Martelli MF. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:254. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Colombo E, Bonetti P, Lazzerini Denchi E, Martinelli P, Zamponi R, Marine JC, Helin K, Falini B, Pelicci PG. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:8874. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.20.8874-8886.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Colombo E, Martinelli P, Zamponi R, Shing DC, Bonetti P, Luzi L, Volorio S, Bernard L, Pruneri G, Alcalay M, Pelicci PG. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3044. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.den Besten W, Kuo ML, Williams RT, Sherr CJ. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1593. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.11.2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sherr CJ. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:663. doi: 10.1038/nrc1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ayrault O, Andrique L, Larsen CJ, Seite P. Oncogene. 2004;23:8097. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sugimoto M, Kuo ML, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ. Mol Cell. 2003;11:415. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Datta K, Sundberg C, Karumanchi SA, Mukhopadhyay D. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Snyder EL, Meade BR, Saenz CC, Dowdy SF. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E36. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Plescia J, Salz W, Xia F, Pennati M, Zaffaroni N, Daidone MG, Meli M, Dohi T, Fortugno P, Nefedova Y, Gabrilovich DI, Colombo G, Altieri DC. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:457. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Midgley CA, Desterro JM, Saville MK, Howard S, Sparks A, Hay RT, Lane DP. Oncogene. 2000;19:2312. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Daujat S, Neel H, Piette J. Trends Genet. 2001;17:459. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02369-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ganguli G, Wasylyk B. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bjornsti MA, Houghton PJ. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:335. doi: 10.1038/nrc1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fingar DC, Blenis J. Oncogene. 2004;23:3151. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jefferies HB, Fumagalli S, Dennis PB, Reinhard C, Pearson RB, Thomas G. EMBO J. 1997;16:3693. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dasgupta B, Yi Y, Chen DY, Weber JD, Gutmann DH. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2755. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Faderl S, Kantarjian HM, Manshouri T, Chan CY, Pierce S, Hays KJ, Cortes J, Thomas D, Estrov Z, Albitar M. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:1855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Faderl S, Estrov Z, Kantarjian HM, Thomas D, Cortes J, Manshouri T, Chan CC, Hays KJ, Pierce S, Albitar M. Cytokines Cell Mol Ther. 1999;5:159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Faderl S, Kantarjian HM, Estey E, Manshouri T, Chan CY, Rahman Elsaied A, Kornblau SM, Cortes J, Thomas DA, Pierce S, Keating MJ, Estrov Z, Albitar M. Cancer. 2000;89:1976. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001101)89:9<1976::aid-cncr14>3.3.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hofmann WK, Tsukasaki K, Takeuchi N, Takeuchi S, Koeffler HP. Leuk Lymphoma. 2001;42:1107. doi: 10.3109/10428190109097731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhang J, Martins CR, Fansler ZB, Roemer KL, Kincaid EA, Gustafson KS, Heitjan DF, Clark DP. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6544. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Simon M, Park TW, Koster G, Mahlberg R, Hackenbroch M, Bostrom J, Loning T, Schramm J. J Neurooncol. 2001;55:149. doi: 10.1023/a:1013863630293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bostrom J, Meyer-Puttlitz B, Wolter M, Blaschke B, Weber RG, Lichter P, Ichimura K, Collins VP, Reifenberger G. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:661. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61737-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Amatya VJ, Takeshima Y, Inai K. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:705. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Watanabe T, Nakamura M, Yonekawa Y, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2001;101:185. doi: 10.1007/s004010000343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Weihrauch M, Markwarth A, Lehnert G, Wittekind C, Wrbitzky R, Tannapfel A. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:884. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.126880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Amatya VJ, Naumann U, Weller M, Ohgaki H. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2005;110:178. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-1041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Newcomb EW, Alonso M, Sung T, Miller DC. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:115. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(00)80207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Vieth M, Schneider-Stock R, Rohrich K, May A, Ell C, Markwarth A, Roessner A, Stolte M, Tannapfel A. Virchows Arch. 2004;445:135. doi: 10.1007/s00428-004-1042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Dominguez G, Carballido J, Silva J, Silva JM, Garcia JM, Menendez J, Provencio M, Espana P, Bonilla F. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kawamoto K, Enokida H, Gotanda T, Kubo H, Nishiyama K, Kawahara M, Nakagawa M. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;339:790. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.11.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Orlow I, LaRue H, Osman I, Lacombe L, Moore L, Rabbani F, Meyer F, Fradet Y, Cordon-Cardo C. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:105. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65105-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chang LL, Yeh WT, Yang SY, Wu WJ, Huang CH. J Urol. 2003;170:595. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000067626.37837.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Gutierrez MI, Siraj AK, Khaled H, Koon N, El-Rifai W, Bhatia K. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:1268. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gonzalez-Gomez P, Bello MJ, Alonso ME, Aminoso C, Lopez-Marin I, De Campos JM, Isla A, Gutierrez M, Rey JA. Int J Mol Med. 2004;13:93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Prowse AH, Schultz DC, Guo S, Vanderveer L, Dangel J, Bove B, Cairns P, Daly M, Godwin AK. J Med Genet. 2003;40:e102. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.8.e102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Silva J, Silva JM, Dominguez G, Garcia JM, Cantos B, Rodriguez R, Larrondo FJ, Provencio M, Espana P, Bonilla F. J Pathol. 2003;199:289. doi: 10.1002/path.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Dominguez G, Silva J, Garcia JM, Silva JM, Rodriguez R, Munoz C, Chacon I, Sanchez R, Carballido J, Colas A, Espana P, Bonilla F. Mutat Res. 2003;530:9. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(03)00133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Silva J, Dominguez G, Silva JM, Garcia JM, Gallego I, Corbacho C, Provencio M, Espana P, Bonilla F. Oncogene. 2001;20:4586. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Yang B, House MG, Guo M, Herman JG, Clark DP. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:412. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tannapfel A, Sommerer F, Benicke M, Weinans L, Katalinic A, Geissler F, Uhlmann D, Hauss J, Wittekind C. J Pathol. 2002;197:624. doi: 10.1002/path.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Takahira T, Oda Y, Tamiya S, Yamamoto H, Kawaguchi K, Kobayashi C, Iwamoto Y, Tsuneyoshi M. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:651. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03324.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Burri N, Shaw P, Bouzourene H, Sordat I, Sordat B, Gillet M, Schorderet D, Bosman FT, Chaubert P. Lab Invest. 2001;81:217. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Shen L, Kondo Y, Hamilton SR, Rashid A, Issa JP. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:626. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Judson H, Stewart A, Leslie A, Pratt NR, Baty DU, Steele RJ, Carey FA. J Pathol. 2006;210:344. doi: 10.1002/path.2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Esteller M, Tortola S, Toyota M, Capella G, Peinado MA, Baylin SB, Herman JG. Cancer Res. 2000;60:129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Lind GE, Thorstensen L, Lovig T, Meling GI, Hamelin R, Rognum TO, Esteller M, Lothe RA. Mol Cancer. 2004;3:28. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-3-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lee M, Sup Han W, Kyoung Kim O, Hee Sung S, Sun Cho M, Lee SN, Koo H. Pathol Res Pract. 2006;202:415. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Grafstrom E, Egyhazi S, Ringborg U, Hansson J, Platz A. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2991. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Puig S, Castro J, Ventura PJ, Ruiz A, Ascaso C, Malvehy J, Estivill X, Mascaro JM, Lecha M, Castel T. Melanoma Res. 2000;10:231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Brown VL, Harwood CA, Crook T, Cronin JG, Kelsell DP, Proby CM. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:1284. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Sakuma K, Chong JM, Sudo M, Ushiku T, Inoue Y, Shibahara J, Uozaki H, Nagai H, Fukayama M. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:273. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Hashiguchi Y, Tsuda H, Yamamoto K, Inoue T, Ishiko O, Ogita S. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:988. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.27115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Smeds J, Berggren P, Ma X, Xu Z, Hemminki K, Kumar R. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:645. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.4.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Xing EP, Nie Y, Song Y, Yang GY, Cai YC, Wang LD, Yang CS. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:2704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Tsuchiya T, Sekine K, Hinohara S, Namiki T, Nobori T, Kaneko Y. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2000;120:91. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(99)00255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Huang HY, Illei PB, Zhao Z, Mazumdar M, Huvos AG, Healey JH, Wexler LH, Gorlick R, Meyers P, Ladanyi M. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:548. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Klump B, Hsieh CJ, Dette S, Holzmann K, Kiebetalich R, Jung M, Sinn U, Ortner M, Porschen R, Gregor M. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Sarbia M, Geddert H, Klump B, Kiel S, Iskender E, Gabbert HE. Int J Cancer. 2004;111:224. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Tsujimoto H, Hagiwara A, Sugihara H, Hattori T, Yamagishi H. Pathol Res Pract. 2002;198:785. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Perrone F, Tamborini E, Dagrada GP, Colombo F, Bonadiman L, Albertini V, Lagonigro MS, Gabanti E, Caramuta S, Greco A, Torre GD, Gronchi A, Pierotti MA, Pilotti S. Cancer. 2005;104:159. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Fulci G, Labuhn M, Maier D, Lachat Y, Hausmann O, Hegi ME, Janzer RC, Merlo A, Van Meir EG. Oncogene. 2000;19:3816. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Ghimenti C, Fiano V, Chiado-Piat L, Chio A, Cavalla P, Schiffer D. J Neurooncol. 2003;61:95. doi: 10.1023/a:1022127302008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Labuhn M, Jones G, Speel EJ, Maier D, Zweifel C, Gratzl O, Van Meir EG, Hegi ME, Merlo A. Oncogene. 2001;20:1103. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Weber A, Wittekind C, Tannapfel A. Pathol Res Pract. 2003;199:391. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Weber A, Bellmann U, Bootz F, Wittekind C, Tannapfel A. Virchows Arch. 2002;441:133. doi: 10.1007/s00428-002-0637-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Lang JC, Borchers J, Danahey D, Smith S, Stover DG, Agrawal A, Malone JP, Schuller DE, Weghorst CM, Holinga AJ, Lingam K, Patel CR, Esham B. Int J Oncol. 2002;21:401. doi: 10.3892/ijo.21.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Jin M, Piao Z, Kim NG, Park C, Shin EC, Park JH, Jung HJ, Kim CG, Kim H. Cancer. 2000;89:60. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000701)89:1<60::aid-cncr9>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Ito T, Nishida N, Fukuda Y, Nishimura T, Komeda T, Nakao K. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:355. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1302-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Peng CY, Chen TC, Hung SP, Chen MF, Yeh CT, Tsai SL, Chu CM, Liaw YF. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:1265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Yamamoto H, Min Y, Itoh F, Imsumran A, Horiuchi S, Yoshida M, Iku S, Fukushima H, Imai K. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002;33:322. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Carrasco DR, Fenton T, Sukhdeo K, Protopopova M, Enos M, You MJ, Di Vizio D, Nogueira C, Stommel J, Pinkus GS, Fletcher C, Hornick JL, Cavenee WK, Furnari FB, Depinho RA. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:379. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Iwato M, Tachibana O, Tohma Y, Arakawa Y, Nitta H, Hasegawa M, Yamashita J, Hayashi Y. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Cairns P. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1022:40. doi: 10.1196/annals.1318.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Papp T, Schipper H, Pemsel H, Bastrop R, Muller KM, Wiethege T, Weiss DG, Dopp E, Schiffmann D, Rahman Q. Int J Oncol. 2001;18:425. doi: 10.3892/ijo.18.2.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Perrone F, Tabano S, Colombo F, Dagrada G, Birindelli S, Gronchi A, Colecchia M, Pierotti MA, Pilotti S. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:4132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Kourea HP, Orlow I, Scheithauer BW, Cordon-Cardo C, Woodruff JM. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1855. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65504-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Hernandez L, Bea S, Pinyol M, Ott G, Katzenberger T, Rosenwald A, Bosch F, Lopez-Guillermo A, Delabie J, Colomer D, Montserrat E, Campo E. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2199. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Inda MM, Munoz J, Coullin P, Fauvet D, Danglot G, Tunon T, Bernheim A, Castresana JS. Histopathology. 2006;48:579. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Frank AJ, Hernan R, Hollander A, Lindsey JC, Lusher ME, Fuller CE, Clifford SC, Gilbertson RJ. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2004;121:137. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Landi MT, Goldstein AM, Tsang S, Munroe D, Modi W, Ter-Minassian M, Steighner R, Dean M, Metheny N, Staats B, Agatep R, Hogg D, Calista D. J Med Genet. 2004;41:557. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.016907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.FitzGerald MG, Harkin DP, Silva-Arrieta S, MacDonald DJ, Lucchina LC, Unsal H, O'Neill E, Koh J, Finkelstein DM, Isselbacher KJ, Sober AJ, Haber DA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Blokx WA, Ruiter DJ, Verdijk MA, de Wilde PC, Willems RW, de Jong EM, Ligtenberg MJ. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:125. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000146003.00727.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Oda Y, Yamamoto H, Takahira T, Kobayashi C, Kawaguchi K, Tateishi N, Nozuka Y, Tamiya S, Tanaka K, Matsuda S, Yokoyama R, Iwamoto Y, Tsuneyoshi M. J Pathol. 2005;207:410. doi: 10.1002/path.1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Perrone F, Oggionni M, Birindelli S, Suardi S, Tabano S, Romano R, Moiraghi ML, Bimbi G, Quattrone P, Cantu G, Pierotti MA, Licitra L, Pilotti S. Int J Cancer. 2003;105:196. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Gonzalez-Gomez P, Bello MJ, Arjona D, Alonso ME, Lomas J, De Campos JM, Kusak ME, Gutierrez M, Sarasa JL, Rey JA. Oncol Rep. 2003;10:1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Pinyol M, Hernandez L, Martinez A, Cobo F, Hernandez S, Bea S, Lopez-Guillermo A, Nayach I, Palacin A, Nadal A, Fernandez PL, Montserrat E, Cardesa A, Campo E. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1987. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65071-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Zochbauer-Muller S, Fong KM, Virmani AK, Geradts J, Gazdar AF, Minna JD. Cancer Res. 2001;61:249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Jarmalaite S, Kannio A, Anttila S, Lazutka JR, Husgafvel-Pursiainen K. Int J Cancer. 2003;106:913. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Hsu HS, Wang YC, Tseng RC, Chang JW, Chen JT, Shih CM, Chen CY. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4734. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Nicholson SA, Okby NT, Khan MA, Welsh JA, McMenamin MG, Travis WD, Jett JR, Tazelaar HD, Trastek V, Pairolero PC, Corn PG, Herman JG, Liotta LA, Caporaso NE, Harris CC. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Watanabe T, Yokoo H, Yokoo M, Yonekawa Y, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2001;60:1181. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.12.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Godfraind C, Rousseau E, Ruchoux MM, Scaravilli F, Vikkula M. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2003;29:462. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.2003.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Shahnavaz SA, Bradley G, Regezi JA, Thakker N, Gao L, Hogg D, Jordan RC. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Ishida E, Nakamura M, Ikuta M, Shimada K, Matsuyoshi S, Kirita T, Konishi N. Oral Oncol. 2005;41:614. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Lim KP, Sharifah H, Lau SH, Teo SH, Cheong SC. Oncol Rep. 2005;14:963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Viswanathan M, Tsuchida N, Shanmugam G. Oral Oncol. 2001;37:341. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Kannan K, Munirajan AK, Krishnamurthy J, Bhuvarahamurthy V, Mohanprasad BK, Panishankar KH, Tsuchida N, Shanmugam G. Int J Oncol. 2000;16:585. doi: 10.3892/ijo.16.3.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Oh JH, Kim HS, Kim HH, Kim WH, Lee SH. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;442:216. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000188063.56091.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Nakamura M, Sakaki T, Hashimoto H, Nakase H, Ishida E, Shimada K, Konishi N. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Nakamura M, Ishida E, Shimada K, Nakase H, Sakaki T, Konishi N. Oncology. 2006;70:212. doi: 10.1159/000094322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Zhang SJ, Endo S, Saito T, Kouno M, Kuroiwa T, Washiyama K, Kumanishi T. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:38. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00003.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Konishi N, Nakamura M, Kishi M, Nishimine M, Ishida E, Shimada K. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1207. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62547-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Furonaka O, Takeshima Y, Awaya H, Ishida H, Kohno N, Inai K. Pathol Int. 2004;54:549. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2004.01663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Kawada Y, Nakamura M, Ishida E, Shimada K, Oosterwijk E, Uemura H, Hirao Y, Chul KS, Konishi N. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2001;92:1293. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2001.tb02152.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Nishimine M, Nakamura M, Kishi M, Okamoto M, Shimada K, Ishida E, Kirita T, Konishi N. Oncol Rep. 2003;10:555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187.Brucher BL, Geddert H, Langner C, Hofler H, Fink U, Siewert JR, Sarbia M. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1298. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 188.Kreimer-Erlacher H, Seidl H, Back B, Cerroni L, Kerl H, Wolf P. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:676. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 189.Kubo Y, Urano Y, Matsumoto K, Ahsan K, Arase S. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;232:38. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 190.Gardie B, Cayuela JM, Martini S, Sigaux F. Blood. 1998;91:1016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 191.Sarkar S, Julicher KP, Burger MS, Della Valle V, Larsen CJ, Yeager TR, Grossman TB, Nickells RW, Protzel C, Jarrard DF, Reznikoff CA. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 192.Sato F, Harpaz N, Shibata D, Xu Y, Yin J, Mori Y, Zou TT, Wang S, Desai K, Leytin A, Selaru FM, Abraham JM, Meltzer SJ. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 193.Chapman EJ, Harnden P, Chambers P, Johnston C, Knowles MA. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5740. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 194.Morris MR, Hesson LB, Wagner KJ, Morgan NV, Astuti D, Lees RD, Cooper WN, Lee J, Gentle D, Macdonald F, Kishida T, Grundy R, Yao M, Latif F, Maher ER. Oncogene. 2003;22:6794. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 195.Soufir N, Daya-Grosjean L, de La Salmoniere P, Moles JP, Dubertret L, Sarasin A, Basset-Seguin N. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1841. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.22.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]