Abstract

Atherosclerosis and related cardiovascular diseases represent one of the greatest threats to human health worldwide. Despite important progress in prevention and treatment, these conditions still account for one third of all deaths annually. Often presented together with obesity, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes, these chronic diseases are strongly influenced by pathways that lie at the interface of chronic inflammation and nutrient metabolism. Here I discuss recent advances in the study of endoplasmic reticulum stress as one mechanism that links immune response with nutrient sensing in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and its complications.

A prevailing view on the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis has focused on abnormalities in lipid metabolism1. However, it has subsequently become clear that inflammation is also central to this pathology2,3. Whereas the engagement of innate and adaptive immune response in atherogenesis has been clearly shown2,4-6, the mechanisms that link metabolic input to immune output still remain poorly understood. Studies in the past decade have established that macrophages and other immune effectors, such as lymphocytes, neutrophils and mast cells, migrate to vascular lesions during the course of atherosclerosis. Similarly, in obesity, the adipose tissue also attracts immune cells4,7-11, which contribute to chronic inflammation—a hallmark of obesity and chronic metabolic disease6.

Much remains unclear about the mechanisms involved in this chronic, low-grade immune response, but its clinical importance is now widely accepted. In obesity, this metabolically driven immune response probably represents a unique phenomenon that I will refer to as ‘metaflammation’6. In all conditions featuring metaflammation, whether it occurs in the obese adipose tissue or in atherosclerotic plaques, a remaining and crucial gap in our understanding is the mechanistic basis by which metabolic signals modify immune effectors or signaling networks to elicit the unusual chronic inflammatory responses. Here I will primarily discuss a key immune cell—the macrophage—and its involvement in lipotoxic responses during atherosclerosis, focusing on its role in pathogenesis through alterations in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER).

ER stress in atherosclerosis

Under conditions that challenge ER function, particularly folding capacity, the ER mounts an adaptive response—the unfolded protein response (UPR)—as a protective mechanism12,13. In eukaryotic cells, three ER-associated proteins are crucial during the UPR: PKR-like eukaryotic initiation factor 2A kinase (PERK), inositol-requiring enzyme-1 (IRE1) and activating transcription factor-6 (ATF6). In a stress-free ER, these three trans-membrane proteins are bound by a chaperone, BiP (also known as GRP78), in their luminal domains and rendered inactive12,13. Accumulation of improperly folded proteins and increased protein cargo in the ER results in oligomerization and activation of PERK and IRE1, at least in part owing to resolution of interactions with BiP, and their engagement of downstream signaling pathways12,13.

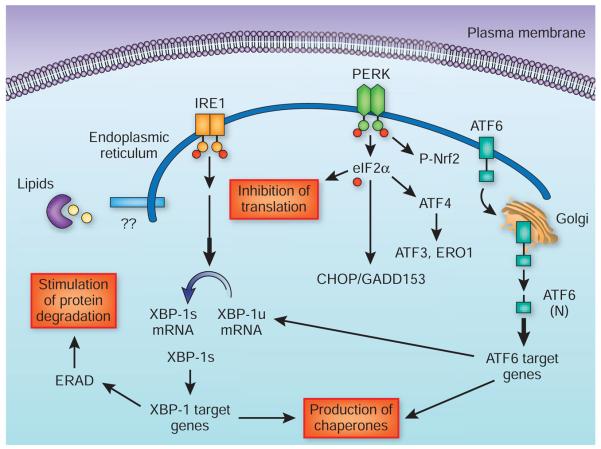

In broad terms, the UPR has three arms: (i) PERK phosphorylates eukaryotic initiation factor-α (eIF2a) to suppress general protein translation12; (ii) IRE1 activation leads to recruitment of several signaling molecules that can engage inflammatory and survival-related signals, and activation of its RNase function leads to splicing and production of an active transcription factor called X box–binding protein 1 (XBP-1)13; and (iii) ATF6 translocates to the Golgi apparatus, where it is processed by two proteases to produce an active transcription factor14. Together, these three arms of the UPR act together to reduce general protein synthesis, facilitate protein degradation and increase folding capacity to resolve ER stress (Fig. 1). But, if unsuccessful, they can also lead to cell death12.

Figure 1.

Canonical unfolded protein response. The unfolded protein response (UPR) results in the inhibition of translation, facilitated protein degradation and production of ER chaperones and other molecules that restore the ER folding environment. These activities are signaled through three UPR sensors—PERK, IRE1a and ATF6—that mediate the canonical response pathways. PERK phosphorylates eIF2a to attenuate general protein translation. It can also regulate the activity of several transcription factors such as ATF4, ATF3 and nuclear factor E2–related factor-2 (Nrf2). Upon autophosphorylation, the RNase activity of IRE1a results in the production of spliced and active XBP-1, leading to the expression and production of ER chaperones and components of the ER-associated degradation (ERAD) process. ATF6 moves to the Golgi apparatus, where it is proteolytically processed to generate an active transcription factor (ATF6(N)) that stimulates the expression of chaperones and XBP-1. There may be additional and unknown aspects of UPR, especially related to the sensing of nutrients and mediation of metabolic adaptations. ERO1, endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreduction-1.

There are several ways in which ER function may influence the course of atherosclerosis. First, there is a direct connection between lipid metabolism and the UPR, as many key lipogenic pathways are situated in the ER15. For example, XBP1 has a role in ER phosphatidylcholine synthesis and ER membrane expansion16. The existing data support the view that ER stress promotes lipogenesis and hepatic lipid accumulation, although how individual UPR branches are engaged in this activity remains unclear17-20. Chemical or molecular resolution of ER stress can prevent hepatic lipid accumulation and facilitate lipoprotein secretion21-23. Conversely, altering phospholipid metabolism by inhibition of phospholipid synthesis or through increasing phospholipase activity exacerbates ER stress responses, and sphingolipid levels can influence the proper function of the ER24,25.

Second, ER stress leads to abnormal insulin action and promotes hyperglycemia through insulin resistance, stimulation of hepatic glucose production and suppression of glucose disposal. From a metabolic perspective, hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia or both may serve as a bridging mechanism between obesity, type 2 diabetes and atherosclerosis15,17. ER stress may also be linked to the production of inflammatory mediators and reactive oxygen species, which are detrimental for insulin action, lipid metabolism and glucose homeostasis3. It is worth mentioning that an inflammatory environment can also compromise ER function, having a negative impact on metabolic homeostasis and promoting further stress and inflammation.

Third, ER stress drives free cholesterol–induced cell death in macrophages, in a model of cellular free-cholesterol loading26. So, the ER may sense stresses related to lipid status and exposure, relaying this information to pathways related to inflammation and death, at least in some cell types that are crucial in the course of the disease3,26.

Last, the ER can have an important role in adaptive immunity and major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-associated antigen presentation27-29. ER stress, particularly induced by an excess of saturated fats, and activation of UPR can impinge on the adaptive immune system by reducing the processing and presentation of MHC-1–associated peptides27. As mentioned above, there is ample evidence to suggest that the immune system has a dominant role in atherosclerosis, and ER stress–driven autoimmune events may be contributing factors27-29.

Macrophage ER stress and atherosclerosis

Macrophages are crucial in the host defense against pathogens30. Although this process is vital for tissue homeostasis, prolonged macrophage activity can contribute to tissue damage5. Macrophage recruitment to atherosclerotic plaques and adipose tissue (or other organs such as the liver and pancreas) can thereby contribute to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and diabetes, respectively. Understanding the mechanisms that lead to activation of these cells may present opportunities for new therapeutic interventions in metabolic diseases3.

In addition to engulfing superfluous cellular material, macrophages also handle hazardous lipid cargo in the form of modified lipoproteins and saturated fatty acids. Macrophages are particularly vulnerable to lipid-induced toxicity in the setting of metabolic diseases such as diabetes and hyperlipidemia, where the lipid concentration, composition or both are altered26,31. Exposure to such a lipotoxic milieu leads to an adaptive stress response from macrophages, which may eventually drive these cells toward apoptosis. The fate of lipids, particularly cholesterol, is a key determinant of the beneficial or harmful effects of local vascular macrophages. For example, if macrophages assist in the removal of cholesterol from the vessel wall, the result might be beneficial. However, deposition of cholesterol and other lipids can also cause stress and eventually may lead to the death of these cells and to the release of their highly perilous cargo. Similarly, in obesity, macrophages can engulf fatty acids and dying adipocytes with voluminous lipid content. This may be useful early on, but it gradually compromises macrophage function, driving the cells to stress, inflammation and death.

At the later stages of disease (whether atherosclerosis or obesity), macrophage death is generally assumed to have deleterious consequences, such as the rupture of vascular plaques and excess inflammatory environment with exacerbated metabolic dysregulation. It will therefore be important to develop chemical or molecular tools to explore the role of macrophages at different stages of metabolic disease. Would death of macrophages early on during atherosclerosis be beneficial (by preventing inflammation) or detrimental (by preventing clearance of vascular lipids)? Is macrophage survival a prerequisite to prevent plaque rupture? How could one develop strategies to exploit macrophage function for potential treatments? These questions warrant further research.

Perhaps a way to approach the above questions lies in understanding better the toxic effects of lipids—that is, addressing whether the lipotoxic responses and the cell death they induce are signaled through specific molecular pathways, or whether lipotoxicity represents a nonspecific demise of cellular function and viability. If there are specific pathways, then there might be opportunities to manipulate them. In recent years, genes involved in ER stress and the related signaling networks have emerged as potential loci where the metabolic signals engage the inflammatory and stress-signaling networks that are central to metabolic dysfunction in obesity and type 2 diabetes15,17. These observations raise the possibility that ER stress may be a _target for lipotoxicity.

Two additional key observations have stimulated interest in the relevance of ER stress on macrophage function and survival as it relates to atherosclerosis. First, ER stress response pathways are activated in lipid-laden macrophages in rodent and human atherosclerotic lesions at different stages of the disease31-33. Second, in vitro treatment of macrophages with excess cholesterol leads to acute induction of ER stress, and these mechanisms can drive macrophage apoptosis induced by free cholesterol31.

What, then, is the role of macrophage ER stress in atherosclerosis? The answer to this question is likely to be multifaceted and to reside in the stage-specific involvement of different cell types and metabolic pathways in atherosclerosis. Much of current knowledge relates to the later stages of the disease, where macrophage ER stress and the related apoptotic responses in these cells may have a role in plaque vulnerability and acute cardiac death26,31-33. In a similar vein, ER stress and UPR are connected to insulin action, at least in part, by IRE1-mediated c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activation17,34. And, in macrophages, defective insulin action has been related to advanced atherosclerotic lesions, potentially through elevation of ER stress–associated macrophage apoptosis26,35. However, alternative roles for macrophage insulin resistance in atherosclerosis have also been proposed36. Perhaps a useful paradigm to use in studying the role of ER stress in macrophage death and atherosclerosis would be exploring the pathways that control upstream UPR sensing and overall ER folding capacity versus downstream effectors that execute death signals at different stages of the disease. In this context, there have been suggestions of a dual impact of macrophage apoptosis at the various stages of atherosclerosis—that is, macrophage apoptosis promotes early lesion formation but prevents plaque progression at later stages37.

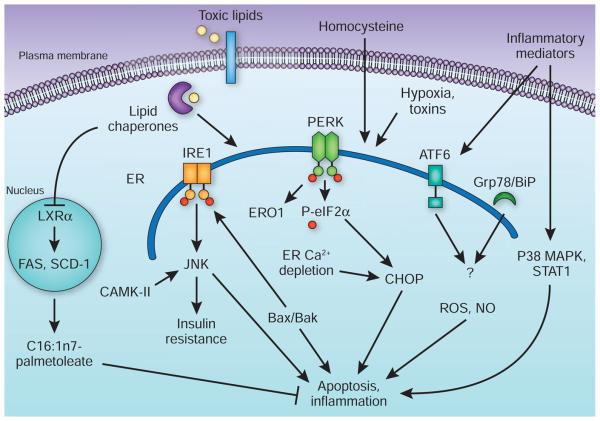

Multiple studies show modulation of signaling events that could have a role downstream of ER stress or upstream of macrophage apoptosis, such as CCAAT box-binding enhancer protein homologous protein (CHOP, also known as GADD153), JNK2, signal transducers and activators of transcription protein-1 (STAT1), p38 mitogen-activated kinase or glycogen synthase kinase-3, can alter the progression of atherosclerosis38-42 (Fig. 2). Collectively, these studies support the idea that macrophage apoptosis and inflammation contribute to the etiology of atherosclerosis, particularly the composition and stability of plaques. However, it is clear that ER stress also emerges in early vascular lesions33. Hence, modulation of ER stress, especially upstream of the apoptotic execution pathways, becomes crucial in understanding the extent of its contribution to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and whether such events affect macrophages or other aspects of disease pathogenesis, such as liver lipid and lipo-protein metabolism and secretion. Recently, through efforts to modify ER folding capacity, clues that may help to answer these questions have started to emerge.

Figure 2.

Macrophage ER stress in inflammation and apoptosis. In atherosclerosis and obesity, excess lipids such as saturated fatty acids or free cholesterol, homocysteinemia, hypoxic stress and other inflammatory and toxic signals can stimulate ER stress and activate the UPR. An upstream mechanism that links these toxic lipids to ER stress involves the action of lipid chaperones through inhibition of LXRα and suppression of a protective lipogenic program that enriches the cells in monounsaturated fatty acids such as palmitoleate (C16:1n7-palmitoleate). Once the cells are committed to death as a result of unresolved ER stress, several well-characterized mechanisms that involve the PERK and IRE1 branches of the UPR act to mediate macrophage apoptosis. These involve association of Bax/Bak with IRE1, activation of JNK, activation of calmodulin kinase II (CaMK-II) owing to abnormal Ca2+ fluxes, and a PERK-mediated increase in CHOP levels and activity. Other factors such as insulin resistance, production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide (NO) production could also contribute to the apoptotic and inflammatory responses. The apoptotic and inflammatory responses may also involve activation of p38 and STAT1, although the links to specific UPR sensors are not entirely clear. The role of the ATF6 branch of the UPR in macrophage function or atherosclerosis remains unknown. p38 MAPK, p38 mitogen-activated kinase. SCD-1, stearoyl-CoA desturase-1.

It has been shown that ER stress can be mitigated by chemical or molecular strategies in chronic metabolic disease, yielding strong preclinical efficacy against obesity, type 2 diabetes and hepatosteatosis17,22,23,43. These discoveries have set the groundwork for interrogating the role of ER stress in atherosclerosis at various stages. In a recent study, administration of a chemical chaperone, phenyl butyric acid, to a genetic model of hypercholesterolemic atherosclerosis associated with apolipoprotein E deficiency resulted in a reduction in the overall vascular lesion burden and in lipid-induced macrophage apoptosis in vitro and in vivo44. Notably, lipid-induced ER stress and apoptosis of cultured macrophages was also mitigated by treatment with a compound that can enhance ER folding capacity, an effect that involved an unexpected, but strong, suppression of the macrophage lipid chaperone aP2 (ref. 44). Hence, aP2 seems to be an obligatory mediator that couples toxic lipids to ER stress in macrophages in vitro and in vivo44. Accordingly, inhibition or genetic deletion of aP2 alleviated macrophage ER stress and substantially protected mice against atherosclerosis acting upstream of apoptotic pathways44-46. These observations support the idea that ER function affects overall vascular lesion development, and they point to aspects of atherosclerosis that reside outside of a role for cell death but include a broader role for ER stress.

These findings also suggest that lipotoxic signals can engage specific pathways to generate their effects in macrophages, and possibly in other cells. Furthermore, they indicate that, although different types of stressor all trigger ER stress by activating the known UPR branches, the coupling of lipids to ER function may potentially involve distinct and unique mechanisms. In the case of aP2, such mechanisms involve activation of an adaptive de novo lipogenic program in macrophages through the regulation of major lipogenic enzymes, such as fatty acid synthase and steaoryl CoA desaturase, by the liver X receptor-α (LXRα)44. This results in the production of desaturation products such as C16:1n7-palmitoleate, a molecule that itself provides relief from lipid-induced ER stress in macrophages, in addition to its reported endocrine effects on liver and muscle47. As a result, macrophages lacking aP2 have substantially higher monounsaturated fatty acid levels and a higher phospholipid-to-cholesterol ratio. These lipid compositional changes may be associated with beneficial changes in the physiochemical properties of cellular membranes when they are exposed to saturated lipids. As the main metabolic culprits in atherosclerosis are lipids, understanding the mechanisms involved in lipid-induced ER stress may provide major insights into disease pathogenesis and potentially uncover unknown aspects of ER biology and the UPR pathway.

It will be fascinating to explore whether specific lipid species are involved in engaging, negatively or positively, ER stress pathways, or are produced during the UPR to regulate nuclear hormone receptor activity or other lipid-responsive molecules. Further studies, using new genetic or chemical models, to modify ER folding capacity upstream of the apoptotic signaling molecules are also needed to define the role of ER stress and UPR branches in different aspects of atherosclerosis, as well as to find how such pathways can be exploited for new therapeutic strategies against this disease. Such studies could also reveal whether the canonical UPR mediators produce their effects only by modifying ER function or through additional pathways that are independent of ER stress.

Multiple cardiovascular disease risk factors, including inflammation, hyperlipidemia, hyperhomocysteinemia and insulin resistance, can lead to the development of ER stress in atherosclerotic lesions3,26,48. The role of ER stress in atherosclerosis is not likely to be related only to activation of apoptotic responses in macrophages but potentially also involves other aspects of macrophage biology related to lipid metabolism, inflammation and metabolic function. Furthermore, the impact of metabolically driven ER stress may not be limited to only macrophages, as other lesion cell types also show signs of ER stress33,49,50. It is unclear whether ER stress in other cells, such as endothelial or smooth muscle cells, or systemic metabolic alterations triggered by ER dysfunction contribute to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Last, liver function is heavily influenced by the condition of the ER, with important implications for dyslipidemia. Further mechanistic research and the development of better genetic and chemical tools should assist in answering these challenging but crucial questions about metabolic regulation of ER function and UPR in atherosclerosis and facilitate the emergence of theraputic opportunities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Studies in the Hotamisligil laboratory are supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health, the American Diabetes Association and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation. I am grateful to the students and fellows who contributed to the studies in my group over the years. My special thanks to E. Erbay for critical discussions, thoughtful comments and help in preparing the manuscript. I regret the possible omission of relevant references to important work by my colleagues owing to space limitations.

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The author declares competing financial interests: details accompany the full-text HTML version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/naturemedicine/.

References

- 1.Rader DJ, Daugherty A. Nature. 2008;451:904–913. doi: 10.1038/nature06796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross R. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;340:115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hotamisligil GS, Erbay E. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:923–934. doi: 10.1038/nri2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weber C, Zernecke A, Libby P. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:802–815. doi: 10.1038/nri2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Libby P. J. Lipid Res. 2009;50:S352–S357. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800099-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hotamisligil GS. Nature. 2006;444:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu H, et al. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;112:1821–1830. doi: 10.1172/JCI19451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishimura S, et al. Nat. Med. 2009;15:914–920. doi: 10.1038/nm.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu J, et al. Nat. Med. 2009;15:940–945. doi: 10.1038/nm.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winer S, et al. Nat. Med. 2009;15:921–929. doi: 10.1038/nm.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feuerer M, et al. Nat. Med. 2009;15:930–939. doi: 10.1038/nm.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ron D, Walter P. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Todd DJ, Lee AH, Glimcher LH. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:663–674. doi: 10.1038/nri2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen X, Shen J, Prywes R. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:13045–13052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110636200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gregor MF, Hotamisligil GS. J. Lipid Res. 2007;48:1905–1914. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R700007-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sriburi R, Jackowski S, Mori K, Brewer JW. J. Cell Biol. 2004;167:35–41. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200406136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozcan U, et al. Science. 2004;306:457–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1103160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee AH, Scapa EF, Cohen DE, Glimcher LH. Science. 2008;320:1492–1496. doi: 10.1126/science.1158042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oyadomari S, Harding HP, Zhang Y, Oyadomari M, Ron D. Cell Metab. 2008;7:520–532. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rutkowski DT, et al. Dev. Cell. 2008;15:829–840. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ota T, Gayet C, Ginsberg HN. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:316–332. doi: 10.1172/JCI32752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ozawa K, et al. Diabetes. 2005;54:657–663. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.3.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ozcan U, et al. Science. 2006;313:1137–1140. doi: 10.1126/science.1128294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramanadham S, et al. Biochemistry. 2004;43:918–930. doi: 10.1021/bi035536m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tessitore A, et al. Mol. Cell. 2004;15:753–766. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tabas I. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2009;11:2333–2339. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Granados DP, et al. BMC Immunol. 2009;10:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-10-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Almeida SF, Fleming JV, Azevedo JE, CarmoFonseca M, de Sousa M. J. Immunol. 2007;178:3612–3619. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang L, Jhaveri R, Huang J, Qi Y, Diehl AM. Lab. Invest. 2007;87:927–937. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aqel NM, Ball RY, Waldmann H, Mitchinson MJ. Atherosclerosis. 1984;53:265–271. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(84)90127-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feng B, et al. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:781–792. doi: 10.1038/ncb1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Myoishi M, et al. Circulation. 2007;116:1226–1233. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.682054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou J, Lhotak S, Hilditch BA, Austin RC. Circulation. 2005;111:1814–1821. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000160864.31351.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirosumi J, et al. Nature. 2002;420:333–336. doi: 10.1038/nature01137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han S, et al. Cell Metab. 2006;3:257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baumgartl J, et al. Cell Metab. 2006;3:247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gautier EL, et al. Circulation. 2009;119:1795–1804. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.806158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thorp E, et al. Cell Metab. 2009;9:474–481. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bowes AJ, Khan MI, Shi Y, Robertson L, Werstuck GH. Am. J. Pathol. 2009;174:330–342. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ricci R, et al. Science. 2004;306:1558–1561. doi: 10.1126/science.1101909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seimon TA, et al. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:886–898. doi: 10.1172/JCI37262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lim WS, et al. Circulation. 2008;117:940–951. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.711275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakatani Y, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:847–851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411860200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Erbay E, et al. Nat. Med. 2009;15:1383–1391. doi: 10.1038/nm.2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Makowski L, et al. Nat. Med. 2001;7:699–705. doi: 10.1038/89076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Furuhashi M, et al. Nature. 2007;447:959–965. doi: 10.1038/nature05844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cao H, et al. Cell. 2008;134:933–944. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou J, Austin RC. Biofactors. 2009;35:120–129. doi: 10.1002/biof.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kedi X, Ming Y, Yongping W, Yi Y, Xiaoxiang Z. Atherosclerosis. 2009;207:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Civelek M, Manduchi E, Riley RJ, Stoeckert CJ, Jr., Davies PF. Circ. Res. 2009;105:453–461. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.203711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]