Abstract

The Mouse Genome Database (MGD) is the community model organism database for the laboratory mouse and the authoritative source for phenotype and functional annotations of mouse genes. MGD includes a complete catalog of mouse genes and genome features with integrated access to genetic, genomic and phenotypic information, all serving to further the use of the mouse as a model system for studying human biology and disease. MGD is a major component of the Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI, http://www.informatics.jax.org/) resource. MGD contains standardized descriptions of mouse phenotypes, associations between mouse models and human genetic diseases, extensive integration of DNA and protein sequence data, normalized representation of genome and genome variant information. Data are obtained and integrated via manual curation of the biomedical literature, direct contributions from individual investigators and downloads from major informatics resource centers. MGD collaborates with the bioinformatics community on the development and use of biomedical ontologies such as the Gene Ontology (GO) and the Mammalian Phenotype (MP) Ontology. Major improvements to the Mouse Genome Database include comprehensive update of genetic maps, implementation of new classification terms for genome features, development of a recombinase (cre) portal and inclusion of all alleles generated by the International Knockout Mouse Consortium (IKMC).

INTRODUCTION

The Mouse Genome Database (MGD) is an integrated database of genetic, genomic and phenotypic data for the laboratory mouse (1–3). MGD is a central component of the Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI) database resource (http://www.informatics.jax.org). Other MGI data resources that are integrated with MGD include the Gene Expression Database (GXD) (4), the Mouse Tumor Biology Database (MTB) (5), the Gene Ontology (GO) project (6) and the MouseCyc database of biochemical pathways (7). Data in MGD are updated daily. There are typically four to six major software releases per year to support access and display of new data types. All data and associated utilities are freely and openly available.

The primary data maintained in MGD include mouse genes and other genome features along with their function and phenotype annotations, associations of genome features with nucleotide and protein sequences, genetic and physical maps, associations between human diseases and mouse models, SNPs and other polymorphisms, and mammalian homology data. A recent summary of MGD content is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of MGD data content (1 September 2010)

| MGD data statistics | 1 September 2010 |

|---|---|

| Genes with nucleotide sequence data | 28 837 |

| Genes with protein sequence data | 25 878 |

| Genes with mutant alleles in mice | 12 900 |

| Genes with experimentally based GO annotations | 11 257 |

| Mouse/human orthologs | 17 852 |

| Genes with one or more mutant allelesa | 19 063 |

| Genes with one or more phenotypic allelesb | 8766 |

| Total mutant alleles, including gene trapsa | 570 982 |

| Phenotypic allelesb | 24 997 |

| Genes with _targeted alleles | 11 940 |

| Gene trapped alleles | 531 232 |

| Human diseases with one or more mouse models | 1033 |

| QTLs | 4473 |

| Number of references | 157 509 |

| Mouse RefSNPs | 10 089 892 |

aMutant alleles include those occurring in mice and/or in ES cell lines.

bPhenotypic alleles include only those mutant alleles present in mice.

MGI curatorial staff acquires data by direct data loads from other databases, from direct submission from researchers, and from published literature. To facilitate data integration, MGI employs recognized standards for genetic and genomic nomenclature, and provides functional and phenotypic annotations describing mouse genes, sequences, strains, expression data, alleles and phenotypes. All data associations in MGD are supported with evidence and citations.

Researchers can access MGD data using keyword or ID-based searches, multi-value integrated queries and programmatically using web services. MGD provides vocabulary browsers to support access to database content via GO annotations, Mammalian Phenotype (MP) (8) annotations and Human Disease Term annotations using OMIM (9). The MGI MouseBLAST server allows users to interrogate the MGI database using nucleotide and/or protein sequences. Access to data in MGD is also facilitated by a variety of tab-delimited database reports that are updated nightly and that are available for download via FTP.

MGD collaborates with other large genome informatics resources (i.e. NCBI, Ensembl, UniProt, HGNC) to curate and maintain a comprehensive catalog of mouse genes and other genome features, and to resolve inconsistencies in the representation of mouse genome features. Biological annotations for mouse genes based on MGD curation are incorporated into scores of external informatics resources and software products.

NEW IN 2010

Update genetic map positions

The genetic map (i.e. centiMorgan; cM) positions for genes and markers in MGI have been updated using the data and methods described in Cox et al. (10). The revised standard genetic map described in Cox et al. incorporates over 10 000 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) using a set of 47 families of a heterogeneous mouse population comprising over 3500 meioses. The revised map corrects errors in marker order in earlier consensus genetic maps for the laboratory mouse. The Cox map integrates simple sequence length polymorphisms (SSLP) markers from other genetic maps and with physical maps of the mouse genome. Linear interpolation was used to translate mouse genome coordinates (NCBI Build 37) for genes and markers in MGI to sex-averaged cM locations. The update to the Cox map resulted in the addition of cM locations for over 35 000 genes and genetic markers, almost doubling the number of markers with cM positions. Approximately 11 000 genes and markers in MGI that did not have genome coordinates were not updated to new cM positions; however, the original mapping data for these markers can still be found in the mapping experiment detail pages.

Classification terms for genome features

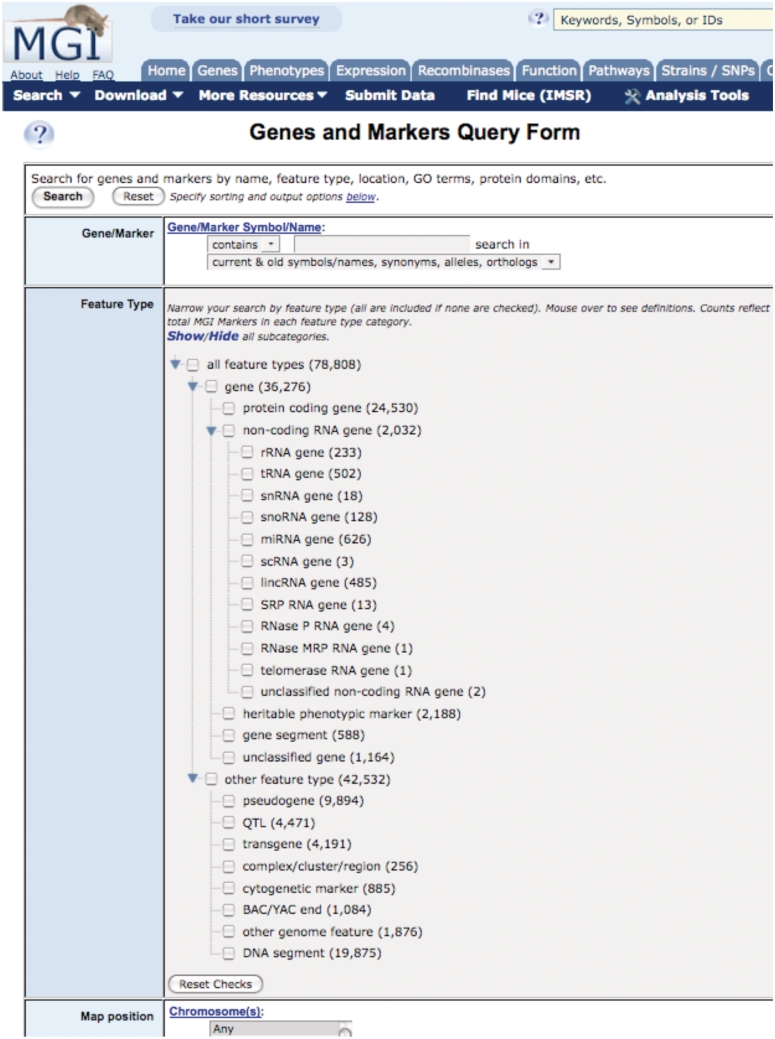

We have implemented new classification terms for genome features that improve the user’s ability to search for specific categories features (e.g. protein-coding gene, non-coding gene, heritable phenotype, etc.). The new genome classifications are accessible from the Genes and Markers Query Form (Figure 1) as well as the MGI instance of BioMart. Most of the classification terms and definitions are derived from the Sequence Ontology (SO) (11) project.

Figure 1.

New classification terms for MGD markers and genome features. The definitions for the terms are displayed when a user ‘mouses over’ a term. Numbers following the term are the current number of entities in that class within MGD. Updated nightly.

Represent mutant alleles generated by the International Knockout Mouse Consortium

The International Knockout Mouse Consortium (IKMC) (12–14), a consortium composed of KOMP (KnockOut Mouse Project) in the USA, EUCOMM (EUropean Conditional Mouse Mutagenesis Program) in Europe, NorCOMM (North American Conditional Mouse Mutagenesis Project) in Canada and TIGM (the Texas Institute of Genomic Medicine) in the US. The goal of IKMC is to use gene-_targeting and gene-trapping technologies in mouse ES cells to mutate all protein-coding genes in the genome and to make these resources available to the scientific community. As new mutations are made in ES cells, alleles are created and accessioned in MGI. Additional information available includes description of the molecular mutation and the ES cell line IDs associated with the allele. Currently over 74 000 alleles in 14 800 genes have been loaded into MGI from the IKMC projects. Plans are underway to incorporate data for those alleles that have been made into mice and phenotyped, so that comparative phenotype analysis can be done with these mutants in the context of all other known mouse phenotypic mutations.

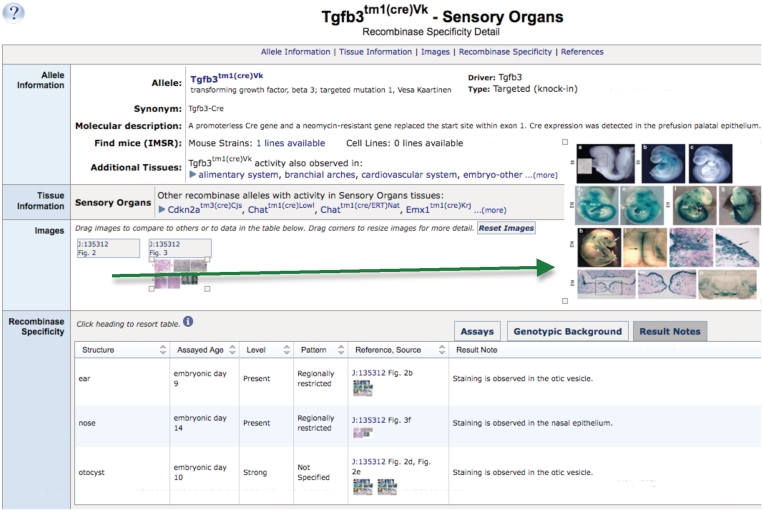

Recombinase (cre) portal

Many of the new alleles being created by the IKMC are ‘conditional-ready’; that is by mating a mouse carrying such an allele to a recombinase bearing transgenic or knockin mouse, a conditional genotype can be produced. These conditional genotypes will have the gene of interest ‘knockedout’ in specific tissues or at specific developmental stages, thus allowing finer analysis of gene function and mitigating potential lethality of effects of a null allele during development. Knowledge of the expression and specificity of the recombinase transgene or knockin allele is key to selecting the appropriate mouse to use in generating conditional genotypes. MGI has released a Recombinase (cre) Data Portal that specifically addresses this need (www.creportal.org). Through this portal, users can access information about all existing cre transgenes and knockins. Data include molecular description of the cre transgene or knockin, the driver / promoter used, inducibility information, publications and availability of cre mice through the IMSR (www.findmice.org, Figure 2). Detailed data, including annotated images showing cre activity/expression for the tissues analyzed are being added as available. Access to phenotypes displayed by cre-deleted mice is provided via integration with MGI’s phenotype data. Currently, there are over 1260 recombinase-containing transgenes and knockin alleles cataloged in the Recombinase (cre) portal.

Figure 2.

Details for the specificity of the recombinase bearing knockin allele, Tgfb3tm1(cre)Vk in sensory organs. Information shown includes molecular description, links to strain availability, other tissues showing recombinase activity and a gallery of images for Tgfb3tm1(cre)Vk in sensory organs. Arrow shows how images may be moved and enlarged to enable better inspection. The table in the lower portion shows detailed annotations for the sensory organ recombinase activities.

Other functional updates and changes

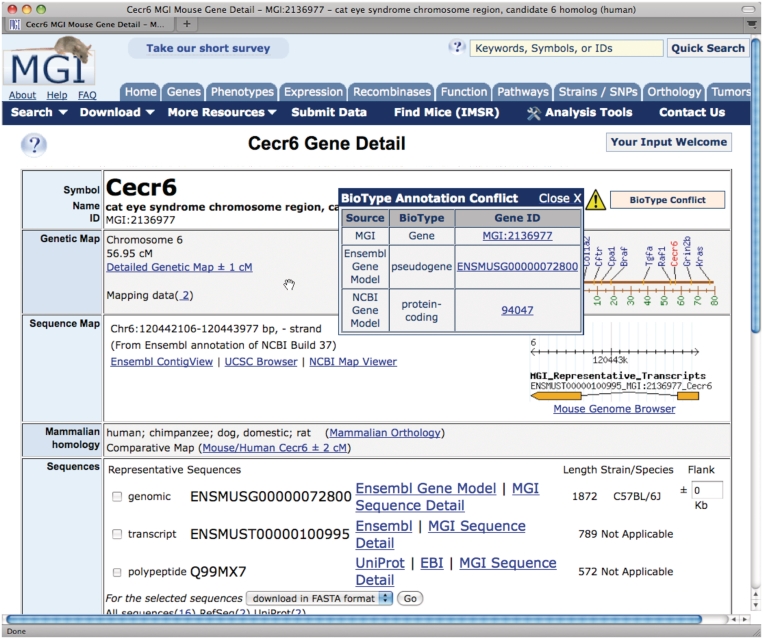

Several minor changes to MGD were incorporated this year including a series of updates to the gene detail pages in regards to integration with other major providers of sequence and gene model data. For example, links are now provided to the underlying evidence that supports gene predictions from VEGA (15), Ensembl (16) and NCBI (17). In addition, if there is a discrepancy in the biotype classification for a gene prediction (i.e. gene versus pseudogene), a ‘biotype conflict’ note now appears on the gene detail page in MGI (Figure 3). The transcript and protein sequences for VEGA and Ensembl gene predictions were incorporated into MGI and can be downloadable from the sequence summary report for each gene record.

Figure 3.

Screenshot showing a biotype conflict note for the Cecr6 gene. In this instance, the Ensembl annotation pipeline has assigned a status of ‘pseudogene’ to Cecr6 and the NCBI annotation pipeline has assigned it a status of ‘protein-coding gene.’ MGI provides links to the underlying evidence for both gene predictions so that users can examine the evidence used to support the gene structure and biotype assignments by different annotation groups.

We now also supply links to Protein Ontology (18) annotations. The PRO provides an ID for each type of protein including protein variants, isoforms and modified forms. As a member of the Protein Ontology Consortium, we are providing detailed annotations for mouse isoforms (in particular). We are also working with the MouseCyc group and PRO to provide specific representations for protein complexes including the exact descriptions and accession IDs for each protein form found in a protein complex. We envision that this approach will eventually support functional annotations to specific proteins and protein complexes rather than to the more generic ‘gene’.

As genome sequence data emerges for strains of mice other than the C57BL/6J reference genome, it becomes possible to identify strain-specific genes. MGI now provides a ‘strain specific genome feature’ note for these features. For, example, the renin 2 (Ren2; MGI:97899) gene is not present in the reference genome but is found in the genomes of other strains of mice.

OTHER INFORMATION

Mouse gene, allele and strain nomenclature

MGD is the authoritative source of symbols and names for mouse genes, alleles and strains. The nomenclature in MGD follows the guidelines set by the ‘International Committee on Standardized Genetic Nomenclature for Mice’ (http://www.informatics.jax.org/nomen). This official nomenclature is widely disseminated through regular data exchange and curation of shared links between MGI and other bioinformatics resources. MGD staff members work with editors of journal publications to promote adherence to mouse nomenclature standards in publications.

To support consistency of nomenclature across multiple mammalian species, members of the MGD nomenclature group coordinate gene names and symbols with nomenclature specialists from the Human Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC) (19) (http://www.genenames.org/) and the rat genome database (RGD) (20) (http://rgd.mcw.edu). The MGD nomenclature coordinator can be contacted by email (nomen@informatics.jax.org).

Programmatic and bulk data access

Programmatic access is available to select portions of the database through two routes. First, the MGI Web Service accepts SOAP 1.1 and 1.2 requests. For details, see http://www.informatics.jax.org/mgihome/other/web_service.shtml. Second, the MGD BioMart (http://biomart.informatics.jax.org/) is accessible through MartServices. See http://www.biomart.org/martservice.html information on MartServices.

In addition bulk data sets are available for download via FTP reports (ftp://ftp.informatics.jax.org) and via the MGI Batch Query (http://www.informatics.jax.org/javawi2/servlet/WIFetch?page=batchQF).

Electronic data submission

MGD accepts contributed data sets from individuals and organizations for any type of data maintained by the database. The most frequent types of contributed data are mutant and phenotypic allele information originating with the large mouse mutagenesis centers and repositories that contribute to the International Mouse Strain Resource [IMSR, http://www.imsr.org, (21)]. Each electronic submission receives a permanent database accession ID. All data sets are associated with their source, either a publication or an electronic submission reference. Details about data submission procedures can be found at http://www.informatics.jax.org/mgihome/submissions/submissions_menu.shtml.

Suggestions and corrections to the representation of data and information in MGD can be submitted using the ‘Your Input Welcome’ link which appears in the upper right hand corner of gene and allele detail pages.

Community outreach and user support

The MGD resource has full time staff members who are dedicated to user support and training. Members of the User Support team can be contacted via e-mail, web requests, phone or FAX.

| • World wide web: | http://www.informatics.jax.org/mgihome/support/ support.shtml |

| • E-mail access: | mgi-help@informatics.jax.org |

| • Telephone access: | +1 207 288 6445 |

| • Fax access: | +1 207 288 6132 |

MGD User Support staff are available for on-site training on the use of MGD and other MGI data resources. The traveling tutorial program includes lectures, demos and hands-on tutorials that can be customized according to the research interests of the audience.

MGI-LIST (http://www.informatics.jax.org/mgihome/lists/lists.shtml) is a moderated and active email bulletin board supported by the MGD User Support group. The MGI listserve has over 2100 subscribers. On average there are three posts per day, every day.

HIGH LEVEL OVERVIEW OF THE MAIN COMPONENTS AND IMPLEMENTATION

MGD is implemented in the Sybase relational database management system with ∼180 tables within which the biological information is stored. BLAST-able databases and genome assembly files for sequence data are stored outside the relational database. An editing interface (EI) and automated load programs are used to input data into the MGD system. The EI is an interactive, graphical application used by curators. Automated load programs that integrate larger data sets from many sources into the database include quality control (QC) checks and processing algorithms that integrate the bulk of the data automatically and identify issues to be resolved by curators or the data provider. Thus, through EI and automated loads, we acquire and integrate large amounts of data into a high quality, knowledgebase.

Public data access to MGD is provided primarily through the web interface (WI) where users can interactively query and download our data through a web browser. MouseBLAST allows users to do sequence similarity searches against a variety of rodent sequence databases that are updated weekly from selected sequence databases from NCBI, UniProt and other providers. Mouse GBrowse allows users to visualize mouse data sets against the genome as a series of linear tracks. All MGD files and programs are openly and freely available.

We continue to provide MGD BioMart with the addition of new classification terms for genome features. MGD BioMart is updated on a weekly basis. MGD BioMart supports chaining to several other BioMarts including Ensembl, VEGA and RGD. Additional functionalities such as the ability to filter by GO, MP and OMIM terms and including additional information about alleles are planned for future extensions.

CITING MGD

For a general citation of the MGI resource please cite this article. In addition, the following citation format is suggested when referring to data sets specific to the MGD component of MGI: MGD, MGI, The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine (URL: http://www.informatics.jax.org) [Type in date (month, year) when you retrieved the data cited].

FUNDING

National Institutes of Health/National Human Genome Research Institute, The Mouse Genome Database (grant HG000330). Funding for open access charge: (grant HG000330).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Mouse Genome Database Group: M.T. Airey, A. Anagnostopoulos, R. Babiuk, R.M. Baldarelli, M. Baya, J.S. Beal, S.M. Bello, D.W. Bradt, D.L. Burkart, N.E. Butler, J. Campbell, L.E. Corbani, S.L. Cousins, D.J. Dahmen, H. Dene, M.E. Dolan, H.R. Drabkin, K.L. Forthofer, D.E. Geel, M. Hall, M. Knowlton, J.R. Lewis, L.J. Maltais, M. McAndrews-Hill, S. McClatchy, M.J. McCrossin, D.S. Miers, L.A. Miller, L. Ni, H. Onda, J.E. Ormsby, D.J. Reed, B. Richards-Smith, D.R. Shaw, R. Sinclair, D. Sitnikov, C.L. Smith, P. Szauter, M. Tomczuk, L.L. Washburn, I.T. Witham, Y. Zhu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bult CJ, Kadin JA, Richardson JE, Blake JA, Eppig JT the Mouse Genome Database Group. The Mouse Genome Database: Enhancements and Updates. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D536–D592. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blake JA, Bult CJ, Eppig JT, Kadin JA, Richardson JE the Mouse Genome Database Group. The Mouse Genome Database genotypes::phenotypes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D712–D719. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bult CJ, Eppig JT, Kadin JA, Richardson JE, Blake JA the Mouse Genome Database Group. The mouse genome database (MGD): mouse biology and model systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D724–D728. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith CM, Finger JH, Hayamizu TF, McCright IJ, Eppig JT, Kadin JA, Richardson JE, Ringwald M. The mouse Gene Expression Database (GXD): 2007 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D618–D623. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krupke DM, Begley DA, Sundberg JP, Bult CJ, Eppig JT. The mouse tumor biology database. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:459–465. doi: 10.1038/nrc2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Gene Ontology Consortium. The Gene Ontology in 2010: extensions and refinements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D331–D335. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evsikov AV, Dolan ME, Genrich MP, Pated E, Bult CJ. MouseCyc: a curated biochemical pathways database for the laboratory mouse. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R84. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-8-r84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith CL, Eppig J. The mammalian phenotype ontology: enabling robust annotation and comparative analysis. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2009;1:390–399. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amberger J, Bocchini CA, Scott AF, Hamosh A. McKusick's Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM®) Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D793–D796. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cox A, Ackert-Bicknell CL, Dumont BL, Ding Y, Bell JT, Brockmann GA, Wergedal JE, Bult C, Paigen B, Flint J, et al. A new standard genetic map for the laboratory mouse. Genetics. 2009;182:1335–1344. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.105486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eilbeck K, Lewis SE, Mungall CJ, Yandell M, Stein L, Durbin R, Ashburner M. The sequence ontology: a tool for the unification of genome annotations. Genome Biol. 2005;6:R44. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-5-r44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.nternational Mouse Knockout Consortium. Collins FS, Rossant J, Wurst W. A mouse for all reasons. Cell. 2007;128:97–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins FS, Finnell RH, Rossant J, Wurst W. A new partner for the international knockout mouse consortium. Cell. 2007;129:235. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ringwald M, Iyer V, Mason J, Stone K, Tadepally H, Kadin JA, Bult CJ, Eppig JT, Oakley D, Briois S, et al. The IKMC Web Portal: a central point of entry to data and resources from the International Knockout Mouse Consortium. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq879. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilming LG, Gilbert JGR, Howe K, Trevanion S, Hubbard T, Harrow JL. The vertebrate genome annotation (VEGA) database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D753–D760. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kersey PJ, Lawson D, Birney E, Derwent PS, Haimel M, Herrero J, Keenan S, Kerhornou A, Koscielny G, Kähäri A, et al. Ensembl Genomes: Extending Ensembl across the taxonomic space. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D563–D569. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pruitt KD, Tatusova T, Klimke W, Maglott DR. NCBI reference sequences: current status, policy and new initiatives. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D32–D36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Protein Ontology Consortium. The protein ontology (PRO): a structured representation of protein forms and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq907. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seal R, Gordon S, Lush M, Bruford E, Wright M. genenames.org: the HGNC resources in 2011. Nucleic Acids Res. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq892. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dwinell M, Worthey EA, Shimoyama M, Bakir-Gungor B, DePons J, Laulederkind S, Lowry T, Nigram R, Petri V, Smith J, et al. The Rat Genome Database 2009: variation, ontologies and pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D744–D749. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eppig JT, Strivens M. Finding a mouse: the International Mouse Strain Resource. Trends Genet. 1999;15:81–88. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01665-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]