Abstract

The Peutz-Jegher syndrome tumor-suppressor gene encodes a protein-threonine kinase, LKB1, which phosphorylates and activates AMPK [adenosine monophosphate (AMP)–activated protein kinase]. The deletion of LKB1 in the liver of adult mice resulted in a nearly complete loss of AMPK activity. Loss of LKB1 function resulted in hyperglycemia with increased gluconeogenic and lipogenic gene expression. In LKB1-deficient livers, TORC2, a transcriptional coactivator of CREB (cAMP response element–binding protein), was dephosphorylated and entered the nucleus, driving the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α), which in turn drives gluconeogenesis. Adenoviral small hairpin RNA (shRNA) for TORC2 reduced PGC-1α expression and normalized blood glucose levels in mice with deleted liver LKB1, indicating that TORC2 is a critical _target of LKB1/AMPK signals in the regulation of gluconeogenesis. Finally, we show that metformin, one of the most widely prescribed type 2 diabetes therapeutics, requires LKB1 in the liver to lower blood glucose levels.

Introduction

The adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a conserved regulator of the cellular response to low energy, and it is activated when intracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) concentrations decrease and AMP concentrations increase in response to nutrient deprivation and pathological stresses (1). In budding yeast, the AMPK homolog Snf1 is activated in response to glucose limitation. In mammals, AMPK has a critical role in many metabolic processes, including glucose uptake and fatty acid oxidation in muscle, fatty acid synthesis and gluconeogenesis in the liver, and the regulation of food intake in the hypothalamus (1-4). AMPK exists as a heterotrimer, composed of the catalytic kinase α subunit and two associated regulatory subunits, β and γ (1). Upon energy stress, AMP directly binds to tandem repeats of crystathionine-β synthase (CBS) domains in the AMPK γ subunit, causing a conformation change that exposes the activation loop in the α subunit, allowing it to be phosphorylated by an upstream kinase (1). The sequence flanking the critical activation loop threonine (Thr172 in human AMPKα) is conserved across species, and its phosphorylation is absolutely required for AMPK activation.

Three papers (5-7) recently reported that the kinase LKB1 is biochemically sufficient to activate AMPK in vitro and is genetically required for AMPK activation by energy stress in a number of mammalian cell lines. Because of this potent connection to AMPK, we began to consider the possibility that LKB1 might normally function as a central regulator of organismal metabolism. In the liver, AMPK is regulated in response to adipokines such as adiponectin and resistin, which serve to stimulate and inhibit AMPK activation, respectively (8, 9). Exercise and several current diabetes therapeutics activate AMPK in muscle and in liver and are thought to therapeutically act in part through stimulation of this pathway in those tissues (10-16). However, Ca2+ calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase β (CAMKKβ) also activates AMPK (14-16). CAMKKβ phosphorylates and activates AMPK in response to calcium, whereas LKB1 appears to be responsible for regulating AMPK under energy stress conditions that involve the accumulation of intracellular AMP (17-20). Moreover, in budding yeast, there are three AMPK kinases (AMPKKs) that are functionally redundant, and all three contribute to metabolic regulation (21-24). Therefore, it was unclear whether LKB1, CAMKKβ, or another AMPKK might regulate AMPK activity in critical metabolic tissues in mammals. We genetically deleted LKB1 in adult mouse liver and examined its role in AMPK activation and the effect of the loss of this pathway on glucose homeostasis. We also examined the therapeutic response to metformin, which is a drug widely used to lower blood glucose concentrations in diabetes patients. Finally, we have defined a signaling pathway by which LKB1 regulates a specific CREB (cAMP response element–binding protein) coactivator that serves as a rate-limiting switch controlling gluconeogenesis in the liver.

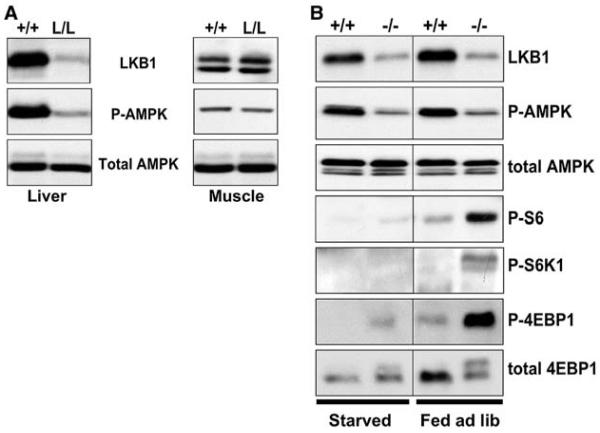

LKB1 deletion in liver results in loss of AMPK activation

We generated cohorts of mice that were either wild-type for LKB1 or were homozygous for a conditional floxed allele of LKB1 (25) by breeding LKB1lox/+ males to LKB1lox/+ females. The resulting 8-week-old male mice of both LKB1+/+ and LKB1lox/lox (henceforth referred to as +/+ and L/L, respectively) genotypes were tail-vein injected with adenovirus expressing Cre recombinase from the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter (26). Because of the high tropism of adenovirus for hepatocytes (27), we observed >95% deletion of LKB1 protein in the livers of the L/L, but not +/+, animals injected with adenovirus Cre, with no signs of deletion in muscle, pancreas, or spleen tissue, as judged by immunoblotting of proteins from lysates of these tissues (Fig. 1A and fig. S2). We expect that only hepatocytes are susceptible to adenoviral infection, and the failure to observe 100% deletion of LKB1 in total tissue extracts from liver may reflect the presence of supporting endothelial and stromal cells in this tissue.

Fig. 1.

Requirement of LKB1 for AMPK activation in liver. (A) Immunoblotting of liver and muscle protein lysates. Two weeks after adenoviral Cre injection, organs were collected from the mice of the indicated genotypes and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Proteins from total-cell extracts of liver or muscle were immunoblotted for LKB1, phospho-Thr172 AMPK (P-AMPK), or total AMPKα. (B) Regulation of mTOR signaling. The mTOR kinase directly phosphorylates two effectors: the translational initiation inhibitor 4E-BP1, and the ribosomal S6 kinase (S6K1). mTOR-activated S6K1 then phosphorylates ribosomal S6. Thus, the level of phosphorylation of 4EBP1, S6K1, and S6 reflect the level of mTOR activation within the cell. Two weeks after adenoviral Cre injection, mice of the indicated genotypes were fasted for 18 hours overnight or fed ad libitium (ad lib) and then killed. Total-cell extracts were made from liver or muscle and immunoblotted with indicated antibodies to examine AMPK activation and mTOR activation in wild-type and LKB1-deficient livers after an 18-hour fast or under ad lib fed conditions, as indicated.

We examined the activation of AMPK using an antibody specific for AMPK that is phosphorylated on Thr172, the critical threonine in the activation loop of AMPK that is phosphorylated by LKB1 (5, 7). The deletion of LKB1 in the liver resulted in a proportional decrease of AMPK phosphorylation at Thr172, suggesting that in this tissue, LKB1 accounts for most of the phosphorylation of AMPK (Fig. 1A). There was no effect of LKB1 loss on the amount of total AMPKα.

One of the critical _targets downstream of LKB1 and AMPK in fibroblasts and tumor cells is the mammalian _target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway (28-30). In response to energy stress, AMPK is activated in an LKB1-dependent manner and phosphorylates the tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2) tumor suppressor, activating it to inhibit mTOR signaling. Loss of LKB1 in intestinal tumors from LKB1+/− mice is accompanied by an increase in mTOR signaling, as detected by the phosphorylation of two of its best-characterized _targets, p70 ribosomal S6 kinase (S6K) and eukaryotic translational initiation factor (eIF) 4E binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) (29). Loss of LKB1 and AMPK activity in liver was also accompanied by increased phosphorylation of 4E-BP1, S6 kinase, and its substrate ribosomal S6 (Fig. 1B). We did not detect any effect of overnight fasting or feeding on the phosphorylation of AMPK. However, mTOR signaling was abolished under starvation conditions in both wild-type and LKB1−/− livers, suggesting that fasting does not inhibit mTOR through AMPK and that positive signals from nutrients and feeding are required to activate mTOR in the liver.

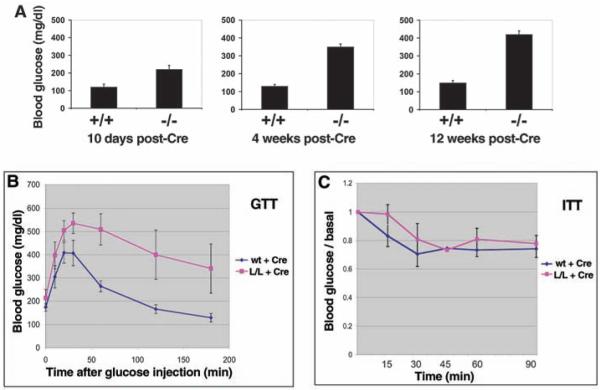

LKB1 deletion in liver causes severe hyperglycemia

AMPK controls two critical liver functions: gluconeogenesis and lipogenesis (1, 31). We examined fasting blood glucose levels in littermate +/+ and L/L mice at various times after administration of Cre. Fasting blood glucose levels were high in the Cre-treated L/L mice at all time points examined, compared with those of Cre-treated wild-type littermates. Resting levels of blood glucose also increased with time (Fig. 2A). Consistent with these findings, the overexpression of a constitutively active AMPKα2 allele in the liver resulted in hypoglycemia (31). Mice lacking hepatic LKB1 also had impaired ability to maintain normal blood glucose concentrations after injection of glucose (Fig. 2B). However, these animals showed a normal reduction in blood glucose in response to insulin injection, suggesting that peripheral glucose uptake was not impaired in these animals (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Glucose homeostasis defects in mice lacking LKB1 in liver. (A) Mice of the indicated genotypes were fasted for 18 hours at indicated times after adenoviral Cre injection, and fasting blood glucose was measured. P < 0.01 at all time points. (B) Glucose-tolerance test (GTT) on mice of indicated genotypes 2 weeks after adenoviral Cre injection. (C) Insulin-tolerance test (ITT) on mice of indicated genotypes 2 weeks after adenoviral Cre injection. No significant difference was observed. Data represents the mean + SEM for six mice of each genotype. Average T0 glucose levels for the wild-type mice = 180 mg/dl; average T0 glucose levels for the L/L mice = 355 mg/dl.

The increase in blood glucose in mice lacking liver LKB1 was accompanied over time by compensatory increases in blood insulin levels, as expected for mice with normal pancreatic function (fig. S3). Despite these changes in blood glucose and insulin profiles, mice lacking LKB1 in the liver did not demonstrate increased body weight compared with their control littermates, even when placed on a high-fat diet for 2 months (fig. S4).

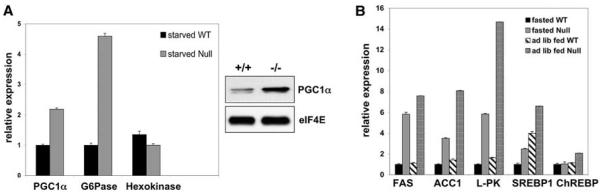

LKB1 loss results in increased gluconeogenic and lipogenic gene expression

The observed hyperglycemia in the mice lacking hepatic LKB1 may result from an inability to appropriately turn off gluconeogenesis. To study the effect of LKB1 loss on gluconeogenesis, we examined the expression of critical gluconeogenic genes by quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). The CREB transcription factor is a critical component of the response to starvation signals and the induction of gluconeogenesis in liver (32). The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α (PGC1α) transcriptional coactivator is an essential transcriptional _target of CREB in this process (32-35). Loss of PGC1α in the liver results in hypoglycemia and a decreased production of gluconeogenic enzymes. PGC1α is thought to mediate transcription downstream of the nuclear receptor hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α (HNF4α) and the transcription factor Foxo1 in the promoters of key gluconeogenic enzymes, including glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase) and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPCK) (fig. S5) (33-39). The expression of G6Pase and PGC1α mRNA was increased in LKB1-deficient livers, whereas no change was observed in the expression of hexokinase mRNA (Fig. 3A). We also detected increased amounts of PGC1α protein in fasting LKB1-deficient mice (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Gluconeogenic and lipogenic gene expression is elevated in LKB1-deficient livers. (A) The left panel shows qRT-PCR examining the expression levels of mRNA for indicated gluconeogenic genes from the livers of mice of indicated genotypes and conditions 3 weeks after Cre administration. Expression was normalized to hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT) and equilibrated to the lowest-value condition for each gene. The right panel shows immunoblot analysis of PGC-1α or eIF4E (loading control) from fasted mice of indicated genotypes 6 weeks after Cre injection. (B) qRT-PCR for lipogenic _target genes on liver samples as in (A). Mice were either fasted or fed ad lib. The induction of lipogenic _targets is lower under ad lib fed conditions than for mice re-fed after fasting conditions (49). qRT-PCR data represent the mean + SEM for samples analyzed in triplicate.

AMPK activity also inhibits lipogenesis (11, 31). Amounts of mRNA encoding the critical lipogenic transcription factor sterol regulatory element–binding protein 1 (SREBP-1) were increased in LKB1-deficient livers along with those several well-described _targets of SREBP-1 and the carbohydrate response element binding protein (ChREBP), which include the following: fatty acid synthase (FAS), acetyl CoA carboxylase (ACC1), and liver pyruvate kinase (L-PK) (Fig. 3B). In contrast, marginal effects were observed on transcription of the ChREBP transcription factor itself. Protein levels of FAS and ACC1 were similarly increased in LKB1-deficient livers (fig. S6).

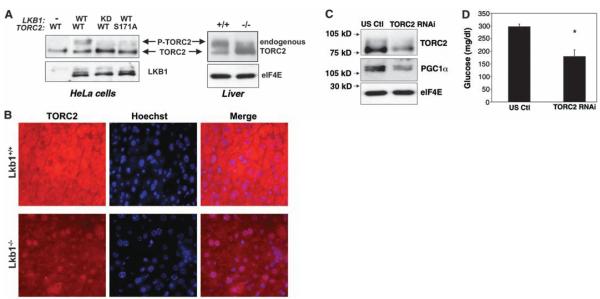

TORC2 is deregulated in LKB1-deficient livers and drives gluconeogenesis

We found that PGC1α mRNA expression was increased, which led us to hypothesize that the activation of gluconeogenesis was occurring at a step before the transcription of gluconeogenic enzymes. The CREB co-activator TORC2 (transducer of regulated CREB activity 2) is a critical regulator of gluconeogenesis in mice (40). TORC2 mediates CREB-dependent transcription of PGC1α and its subsequent gluconeogenic _targets PEPCK and G6Pase. TORC2 is regulated by a series of phosphorylation events, and its nuclear localization is controlled by phosphorylation of Ser171 (numbering for human TORC2) (40, 41). Phosphorylation at this site confers binding of the protein 14-3-3 and sequestration of TORC2 out of the nucleus. The kinase responsible for phosphorylating Ser171 of TORC2 was initially identified as salt-inducible kinase 2 (SIK2), one of three SIKs all related to AMPK (41). Recently, activation of AMPK was also found to phosphorylate TORC2 and regulate cytoplasmic translocation of the coactivator in primary hepatocyte cultures (40). LKB1 phosphorylates and activates of a number of kinases in the AMPK kinase subfamily, including the SIK kinases (42), suggesting that genetic deletion of LKB1 in liver will result in the inactivation of multiple TORC2 Ser171 kinases.

The reintroduction of wild-type, but not catalytically inactive, LKB1 into LKB1-deficient tumor cells resulted in a mobility shift of TORC2 during electrophoresis, indicative of its phosphorylation at Ser171 (Fig. 4A) (40). We next examined whether endogenous TORC2 phosphorylation was affected in the LKB1-deficient livers. TORC2 from untreated wild-type livers was predominantly phosphorylated, whereas much of the TORC2 from LKB1-deficient liver exhibited a faster mobility, consistent with the absence of Ser171 phosphorylation. We also examined the localization of endogenous TORC2 by immunohistochemistry in sections from LKB1+/+ and LKB1−/− livers. TORC2 was predominantly nuclear in LKB1−/− livers, whereas in wild-type mice, TORC2 was predominantly cytoplasmic (Fig. 4B). This dramatic localization change is consistent with Ser171 dephosphorylation being a rate-limiting event for TORC2 nuclear translocation in this physiological setting.

Fig. 4.

Decreased phosphorylation of the TORC2 transcriptional coactivator and increased gluconeogenesis in the LKB1-deficient livers. (A) Requirement of LKB1 for TORC2 phosphorylation at Ser171 and associated mobility shift on SDS-polyacrylamide gel elecrophoresis. (Left) Wild-type (WT) or catalytically-inactive (KD) LKB1 was cotransfected with FLAG-tagged wild-type or Ser171 Ala mutant TORC2 into −/− HeLa cells. Total cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies to LKB1 or FLAG. The correlation between the mobility-shifted TORC2 and phosphorylation at Ser171 has also been previously described (37). (Right) Immunoblot of endogenous TORC2 protein from liver extracts of (ad lib fed) mice of indicated genotypes 2 weeks after adenoviral Cre injection. eIF4E levels were examined as a loading control. (B) Immunohistochemistry of endogenous TORC2 in livers of indicated genotypes analogous to those extracted and immunoblotted in (A). Hoechst dye stains only nuclear DNA; thus, by merging the anti-TORC2 localization with the Hoechst, we observed the presence of TORC2 in the nucleus. In wild-type mice, the Hoescht dye and TORC2 staining are mutually exclusive, whereas in LKB1-deficient livers, there is near complete overlap in the nucleus. (C) TORC2 shRNA in liver reduces TORC2 and PGC1α protein levels. Adenovirus encoding TORC2 shRNA or a control scrambled shRNA (US ctl) was introduced by tail-vein injection into L/L mice that had been tail-vein injected with adenoviral Cre 2 weeks earlier. Five days after adenoviral shRNA injection, mice were fasted for 18 hours. Total-cell lysates were made from the liver and immunoblotted with indicated antibodies. (D) Blood glucose levels in Cre-injected L/L mice reduced by TORC2 shRNA. Adenovirus shRNA was administered as above and fasting glucose levels were monitored. Data represent the mean + SEM for five mice of each group. P < 0.01, t test.

To examine whether the increased nuclear TORC2 is functionally active and responsible for increased gluconeogenesis in mice lacking LKB1 in the liver, we injected these mice with adenoviruses bearing small hairpin RNA (shRNA) for TORC2 or a control scrambled sequence. Five days after administering the shRNA adenoviruses, we examined fasting blood glucose levels and protein levels in the liver. TORC2 protein levels were reduced by more than 70% by the TORC2 shRNA but not by control shRNA. We observed a proportional loss of total PGC1α protein in the TORC2-shRNA–treated mice (Fig. 4C). The reduction of TORC2 and PGC1α protein levels was accompanied by a significant decrease in fasting blood glucose levels in the TORC2-shRNA–treated mice (Fig. 4D). Altogether, these data suggest that TORC2 is a critical downstream _target of LKB1-dependent kinases in the control of gluconeogenesis.

Metformin requires hepatic LKB1 to lower blood glucose

Metformin is an oral biguanide that is one of the most widely prescribed therapeutics for type 2 diabetes worldwide (1, 43). Metformin lowers blood glucose and blood lipid contents, and these effects are thought to be at least partially responsible for its therapeutic benefits. Decreased hepatic gluconeogenesis and increased glucose uptake in skeletal muscle have been proposed to explain the effects of metformin on hyperglycemia. Metformin has been suggested to act through the stimulation of AMPK in peripheral tissues. Consistent with this hypothesis, metformin treatment of hepatocytes results in decreased glucose output and decreased lipogenic gene expression, and these effects were blocked by treatment of the cells with a chemical inhibitor of AMPK or an expression of dominant negative AMPK, respectively (11, 44).

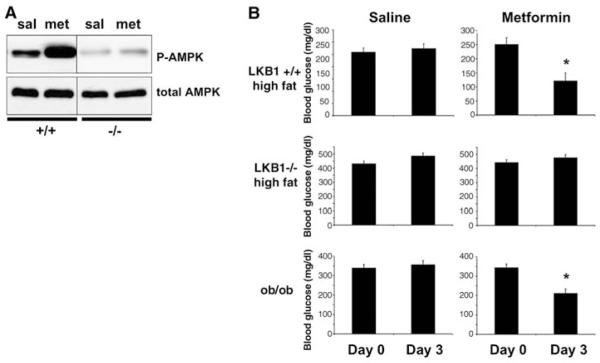

We examined whether metformin treatment of mice increased AMPK activity in the liver in an LKB1-dependent manner. AMPK phosphorylation was increased in livers from wild-type mice injected with metformin, but not in livers deficient in LKB1 (Fig. 5A). We then examined whether metformin was capable of reducing blood glucose levels in mice in which LKB1 was deleted in the liver. To ensure that the regimen of metformin we were using was effective in comparable control mice, we placed adenovirus Cre–treated L/L mice and adenovirus Cre–treated wild-type littermates on a high-fat diet for 6 weeks. We then treated these mice, or ob/ob obese mice, with metformin for 3 days and examined blood glucose levels from fasting animals. Metformin treatment reduced blood glucose by more than 50% in the wild-type mice on a high-fat diet. Metformin treatment also lowered blood glucose in the ob/ob mice by 40%. However, there was no reduction in blood glucose in the mice in which LKB1 had been deleted in the liver.

Fig. 5.

LKB1 in liver is required for the ability of metformin to lower blood glucose. (A) LKB1 is required for metformin to activate AMPK in liver in mice. 8-week-old +/+ or L/L littermate male mice were injected in the tail vein with adenoviral Cre. Two weeks after Cre administration, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 250 mg metformin per kg body weight (mg/kg) in saline or just saline for 3 consecutive days. On the third day, total-cell extracts were made from collected livers 1 hour after metformin administration. Liver extracts were immunoblotted with antibody to phospho-Thr172 AMPK or total AMPK antibodies. (B) LKB1 in liver is required for the ability of metformin to lower blood glucose. 8-week-old +/+ or L/L littermate male mice were injected in the tail vein with adenoviral Cre and placed on a high-fat diet (55% fat, 24% carbohydrate, Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) for 6 weeks. 8-week-old ob/ob male mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory. Mice were fasted for 18 hours, then blood glucose was measured. Starting the next day, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 250 mg/kg metformin in saline or just saline for 3 consecutive days. On the third day, mice were fasted overnight and blood glucose was measured. Data represent the mean + SEM for five mice of each group. *P < 0.001, t test.

Conclusions

Our results provide direct evidence that the LKB1 tumor suppressor is the major upstream activating kinase for AMPK in liver. We cannot rule out minor roles for other kinases, but under all conditions we examined, the loss of LKB1 was mirrored by loss of AMPK phosphorylation. Similarly, LKB1 appears to be the major AMPKK in skeletal muscle (45).

We elucidate here a signal transduction pathway that governs the synthesis of glucose in the liver. The activation of an upstream kinase (LKB1) in turn regulates downstream kinases (AMPK and SIK) that phosphorylate a transcriptional coactivator (TORC2), resulting in its inactivation through sequestration in the cytoplasm. This pathway normally integrates cellular (AMPK) and hormonal (SIK) inputs to negatively regulate transcriptional events that promote synthesis of gluconeogenic enzymes. In the absence of LKB1, no kinase is active to phosphorylate TORC2, and gluconeogenesis occurs without these metabolic checkpoints. This pathway in mammalian liver is functionally analogous to control of feeding on carbon sources in budding yeast. In yeast, switching growth onto nonfermentable sugars activates the AMPK homolog Snf1 through phosphorylation by upstream kinases that are homologous to LKB1. Activated Snf1 then phosphorylates the transcriptional regulator Mig1, which causes its translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, altering gene expression that allows survival under the nutrient-poor environment.

Metformin has been used clinically for decades (43). Our data provide genetic proof that AMPK activation is absolutely required for the glucose-lowering action of metformin in intact animals. The deletion of LKB1 in the liver did not impair AMPK activation in muscle, yet it eliminated the effect of metformin on serum glucose levels. This result suggests that in mice, metformin primarily decreases blood glucose concentrations by decreasing hepatic gluconeogenesis.

LKB1 also acts as a tumor suppressor. Thus, increased CREB-dependent or SREBP-1–dependent transcription could have a role in LKB1-dependent tumorigenesis. Constitutive activation of CREB transcription contributes to oncogenesis in human salivary tumors and clear cell sarcomas (46-48).

These findings reinforce the emerging intimate relationship that exists between physiological control of metabolism and cancer. The mTOR, insulin, and LKB1 pathways represent a fundamental eukaryotic network governing cell growth in response to environmental nutrients. Dysregulation of each contributes to both diabetes and cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Loda for the FAS antibody; J. Luo, A. Shaywitz, and O. Peroni for technical advice; K. Cichowski for help with the manuscript; D. Gwinn and C. Mealmaker for technical assistance; and the University of Iowa Gene Transfer Vector Core, supported in part by NIH and the Roy J. Carver Foundation, for adenoviral Cre preparations. This work was supported by grants GM056203, GM37828, and CA84313 from the NIH to L.C.C., M.M., and R.A.D., respectively. M.M. also was supported in part by the Hillblom Foundation.

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1120781/DC1 Materials and Methods Figs. S1 to S6 References

References and Notes

- 1.Kahn BB, Alquier T, Carling D, Hardie DG. Cell Metab. 2005;1:15. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minokoshi Y, et al. Nature. 2004;428:569. doi: 10.1038/nature02440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson U, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:12005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300557200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim EK, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:19970. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402165200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawley SA, et al. J. Biol. 2003;2:28. doi: 10.1186/1475-4924-2-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaw RJ, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:3329. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woods A, et al. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:2004. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamauchi T, et al. Nat. Med. 2002;8:1288. doi: 10.1038/nm788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banerjee RR, et al. Science. 2004;303:1195. doi: 10.1126/science.1092341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayashi T, Hirshman MF, Kurth EJ, Winder WW, Goodyear LJ. Diabetes. 1998;47:1369. doi: 10.2337/diab.47.8.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou G, et al. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;108:1167. doi: 10.1172/JCI13505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fryer LG, Parbu-Patel A, Carling D. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:25226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park H, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:32571. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201692200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saha AK, et al. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;314:580. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.12.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cleasby ME, et al. Diabetes. 2004;53:3258. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.12.3258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pold R, et al. Diabetes. 2005;54:928. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.4.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawley SA, et al. Cell Metab. 2005;2:9. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hurley RL, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:29060. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woods A, et al. Cell Metab. 2005;2:21. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Birnbaum MJ. Mol. Cell. 2005;19:289. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong SP, Leiper FC, Woods A, Carling D, Carlson M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:8839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533136100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sutherland CM, et al. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:1299. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00459-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong SP, Momcilovic M, Carlson M. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:21804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501887200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCartney RR, Rubenstein EM, Schmidt MC. Curr. Genet. 2005;47:335. doi: 10.1007/s00294-005-0576-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bardeesy N, et al. Nature. 2002;419:162. doi: 10.1038/nature01045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Materials and methods are available as supporting materials on Science Online.

- 27.Huard J, et al. Gene Ther. 1995;2:107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inoki K, Zhu T, Guan KL. Cell. 2003;115:577. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00929-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaw RJ, et al. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:91. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corradetti MN, Inoki K, Bardeesy N, DePinho RA, Guan KL. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1533. doi: 10.1101/gad.1199104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foretz M, et al. Diabetes. 2005;54:1331. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.5.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herzig S, et al. Nature. 2001;413:179. doi: 10.1038/35093131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koo SH, et al. Nat. Med. 2004;10:530. doi: 10.1038/nm1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoon JC, et al. Nature. 2001;413:131. doi: 10.1038/35093050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin J, Handschin C, Spiegelman BM. Cell Metab. 2005;1:361. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rhee J, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:4012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730870100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Puigserver P, et al. Nature. 2003;423:550. doi: 10.1038/nature01667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang L, Rubins NE, Ahima RS, Greenbaum LE, Kaestner KH. Cell Metab. 2005;2:141. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakae J, Kitamura T, Silver DL, Accili D. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;108:1359. doi: 10.1172/JCI12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koo SH, et al. Nature. 2005;437:1109. doi: 10.1038/nature03967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Screaton RA, et al. Cell. 2004;119:61. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lizcano JM, et al. EMBO J. 2004;23:833. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Witters LA. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;108:1105. doi: 10.1172/JCI14178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zang M, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:47898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408149200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sakamoto K, et al. EMBO J. 2005;24:1810. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu L, et al. EMBO J. 2005;24:2391. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zucman J, et al. Nat. Genet. 1993;4:341. doi: 10.1038/ng0893-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Conkright MD, Montminy M. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:457. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shaw RJ, Lamia KA. data not shown.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.