Abstract

Technologies allowing for specific regulation of endogenous genes are valuable for the study of gene functions and have great potential in therapeutics. We created the CRISPR-on system, a two-component transcriptional activator consisting of a nuclease-dead Cas9 (dCas9) protein fused with a transcriptional activation domain and single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) with complementary sequence to gene promoters. We demonstrate that CRISPR-on can efficiently activate exogenous reporter genes in both human and mouse cells in a tunable manner. In addition, we show that robust reporter gene activation in vivo can be achieved by injecting the system components into mouse zygotes. Furthermore, we show that CRISPR-on can activate the endogenous IL1RN, SOX2, and OCT4 genes. The most efficient gene activation was achieved by clusters of 3-4 sgRNAs binding to the proximal promoters, suggesting their synergistic action in gene induction. Significantly, when sgRNAs _targeting multiple genes were simultaneously introduced into cells, robust multiplexed endogenous gene activation was achieved. Genome-wide expression profiling demonstrated high specificity of the system.

Keywords: CRISPR, transcription factor, synthetic biology, gene expression, artificial transcription factor

Introduction

Gene expression is strictly controlled in many biol-ogical processes, such as development and diseases. Transcription factors regulate gene expression by binding to specific DNA sequences at the enhancer and promoter regions of _target genes, and modulate transcription through their effector domains1. Based on the same principle, artificial transcription factors (ATFs) have been generated by fusing various functional domains to a DNA binding domain engineered to bind to the genes of interest, thereby modulating their expression2,3. The capability of regulating endogenous gene expression using ATFs may facilitate the study of the transcriptional network underlying complex biological processes and provide new therapeutic options for diseases. Significant efforts and progress have been made to engineer DNA binding domains with defined specificities. The decipherment of the “code” of DNA binding specificity of zinc finger proteins and transcription activator-like effectors (TALE) has led to the rational design of DNA binding domains to recognize specific nucleotides with certain probability 4,5,6,7,8,9,10. However, binding specificity of these ATFs is usually degenerate, can be difficult to predict and the complex and time-consuming design and generation limits their applications. To study the transcriptional network in a systematic manner, regulating multiple endogenous genes is required, prompting the development of efficient technology for simultaneous regulation of multiple endogenous genes.

CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palin-dromic repeat) and Cas (CRISPR-associated) proteins are utilized by bacteria and archea to defend against viral pathogens11,12. Because the binding of Cas protein is guided by the simple base-pair complementarities between the engineered single guide RNA (sgRNA) and a _target genomic DNA sequence, Cas9 could be directed to specific genomic locus or multiple loci simultaneously, by providing the engineered sgRNAs13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. A recent study described the CRISPRi (CRISPR interference) system, in which the nuclease-deficient dCas9 (D10A; H840A) proteins blocked the transcription apparatus when directed to promoters or gene bodies in bacteria21. A subsequent study demonstrated a more efficient gene repression in eukaryotes by dCas9 fused with a transcription repression domain or exogenous transgene activation when fused with an activation domain22. Two most recent studies showed single endogenous gene activation using dCas9-based activators9,10. To what extent multiple endogenous genes could be regulated simultaneously has not been explored. In this study we report the generation of an RNA-programmable CRISPR-on system, which enables the simultaneous activation of multiple endogenous genes with a defined stoichiometry.

Results

Fusion of nuclease-deficient Cas9 to transactivation domain generated an RNA-programmable transcription factor

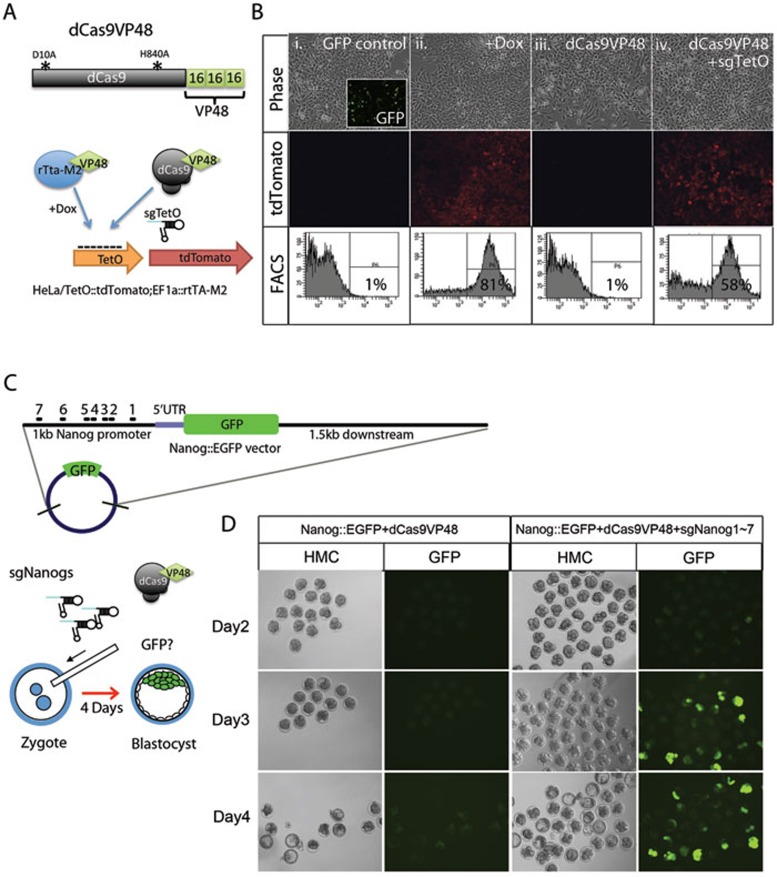

To generate a CRISPR/Cas-based transcription activator (CRISPR-on), we introduced the H840A mutation in the human codon-optimized Cas9(D10A) nickase14 to create a nuclease-deficient dCas9 (H840A; D10A) and fused a 3× minimal VP16 transcriptional activation domain (VP48) to its C-terminus (dCas9VP48) (Figure 1A). We first tested dCas9VP48 in human HeLa cells carrying integrated tdTomato reporter transgene under the control of a Tetracycline-inducible promoter composed of seven copies of rtTA binding sites and a CMV minimal promoter (TetO::tdTomato). As a positive control, these cells constitutively expressed the rtTA transactivator that induces tdTomato expression upon doxycycline treatment (Figure 1B column ii). Transient transfection of dCas9VP48 with sgRNA complementary to rtTA binding site (sgTetO) activated the TetO::tdTomato reporter in the absence of doxycycline at almost the same efficiency as the positive control (Figure 1B column iv). Transfection of dCas9VP48 without sgRNA did not activate tdTomato expression (Figure 1B column iii). Activation of a TetO::tdTomato reporter lasted for about two weeks but became weak afterwards (Supplementary information, Figure S1). Similarly, co-expression of dCas9VP48 with sgTetO activated the tdTomato transgene in mouse NIH3T3 cells carrying an integrated TetO::tdTomato reporter (Supplementary information, Figure S2B column iv), while expression of dCas9VP48 alone did not activate tdTomato expression (Supplementary information, Figure S2B column iii). These results indicate that CRISPR-on activates a transgene reporter robustly in human and mouse cells to a similar level to rtTA in the presence of doxycycline and that the binding of dCas9VP48 to the TetO promoter is strictly dependent on sgTetO. The higher fraction of fluorescent HeLa cells as compared to that in NIH3T3 cells is likely due to higher transfection efficiency.

Figure 1.

CRISPR-on activates exogenous transgenes. (A) Schematic of the dCas9VP48-mediated transgene activation in HeLa cells. dCas9VP48 was generated by fusing dCas9 (indicated by black circle) to VP48 domain (indicated by green dimond). sgRNA complementary to rtTA binding site is indicated by small hairpin labeled sgTetO. (B) dCas9VP48 activates TetO::tdTomato transgene in HeLa cells. Upper panel, phase contrast picture of transfected cells; middle panel, tdTomato signal using fluorescent microscopy; bottom panel, FACS analysis of transfected cells. Column i, cells transfected with GFP plasmid; column ii, cells treated with doxycycline; column iii, cells transfected with dCas9VP48 only; column iv, cells transfected with dCas9VP48 and sgTetO. Cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids and 48 h later were analyzed by flow cytometry for tdTomato expression. (C) Schematic of the dCas9VP48-mediated reporter activation in early mouse embryos. dCas9VP48, Nanog::EGFP vector, and 7 sgRNAs _targeting Nanog promoter were co-injected into mouse zygotes and cultured into blastocyst stage. (D) dCas9VP48/sgRNA can activate gene in vivo. Left panel, embryos injected with dCas9VP48 and Nanog::EGFP vector; right panel, embryos injected with dCas9VP48, Nanog::EGFP vector and sgRNAs _targeting Nanog promoter. Embryos two, three, four days post-injection were shown.

We tested whether CRISPR-on can activate a single-copy transgene in mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs). For this, dCas9VP48 was co-transfected with sgTetO into KH2MSI1 ESCs carrying a Tet-inducible Musashi1 (MSI1) transgene at the Col1A1 locus and the rtTA-M2 in the Rosa26 locus23 (Supplementary information, Figure S3). Transient transfection of dCas9VP48 alone did not activate MSI1 expression (Supplementary information, Figure S3 Lane 1), while co-transfection of dCas9VP48 with sgTetO or addition of doxycycline (positive control) activated MSI1 expression (Supplementary information, Figure S3 Lane 2 and 7). Neither expression of dCas9VP48 with a mutant TetO sgRNA (sgTetO-mut) carrying mismatches to the TetO binding sites (Supplementary information, Figure S3 Lane 3) nor expression of sgTetO with dCas9 lacking an activation domain activated MSI1 expression (Supplementary information, Figure S3 Lane 4).

To further characterize the system, we transfected HEK293T/TetO::tdTomato cells with dCas9 activator and a serial titration of sgRNAs (Supplementary information, Figure S4). We observed a near-linear relationship between the amount of sgTetO transfected and the mean fluorescence by FACS (Supplementary information, Figure S4B), indicating that the level of gene activation could be controlled precisely by using CRISPR-on.

To test whether CRISPR-on can activate genes in vivo, we co-injected a Nanog::EGFP construct containing a 1 kb promoter and 5′ UTR of Nanog into mouse zygotes with the dCas9VP48 plasmid and seven different sgRNAs (sgNanog-1∼7) _targeting the mouse Nanog promoter (Figure 1C and 1D). As a control, the Nanog::EGFP construct was co-injected with dCas9VP48 plasmid only. Two days after injection, a GFP signal was detected in 4-cell embryos by fluorescence microscopy and higher GFP expression was observed in morulae and blastocysts on day 3 and day 4, whereas no GFP signal was observed in control embryos injected only with the Nanog::EGFP construct and dCas9VP48 plasmid. Although Nanog has been reported to be expressed in cleavage stage embryos24, it is likely that the Nanog::EGFP reporter construct used does not include all necessary elements for Nanog expression in the embryo. Thus, the results shown in Figure 1D demonstrate that the dCas9VP48/sgNanogs activator system can specifically activate a GFP transgene by _targeting upstream promoter sequences in mouse embryos.

Activation of endogenous genes

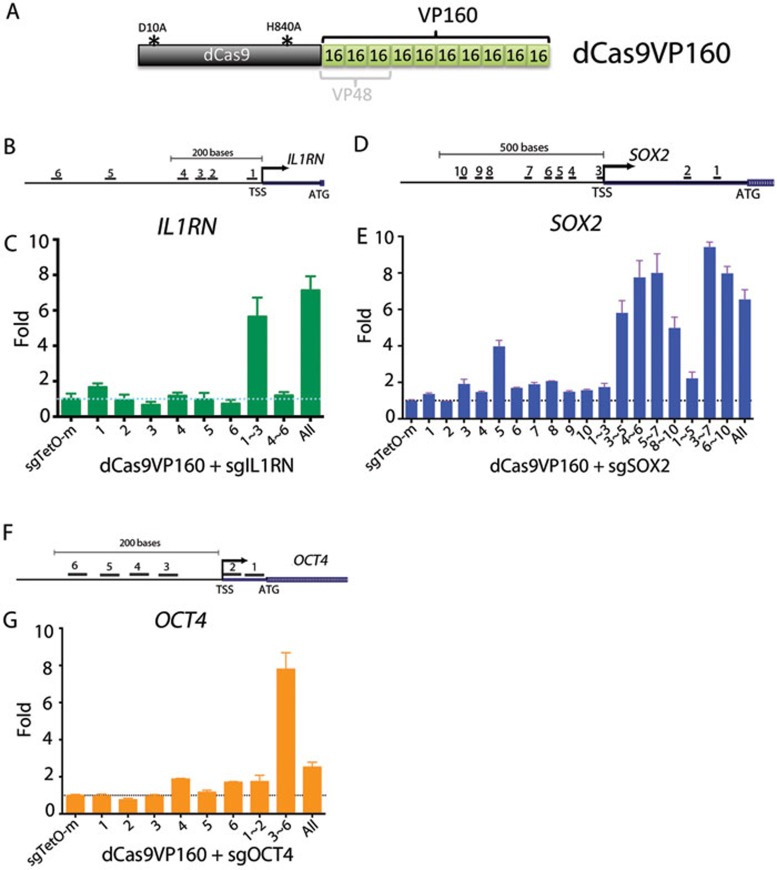

Having established that the CRISPR-on system can activate reporter transgenes, we designed sgRNAs _targeting the endogenous human IL1RN gene and tested their transactivation activity in HEK293T cells. To identify the binding sites most efficient for gene induction, six sgRNAs were designed to span the 1 kb IL1RN promoter (Supplementary information, Figure S5). Initially, we transfected dCas9VP48 with all 6 sgRNAs, but failed to induce IL1RN gene expression (Supplementary information, Figure S5). To test whether a stronger activation domain can activate IL1RN, we fused a VP160 domain containing 10 tandem copies of VP16 motifs with dCas9 to generate dCas9VP160 (Figure 2A). When co-transfected with multiple but not single sgRNAs, dCas9VP160 readily activated IL1RN (Figure 2B and 2C). Transduction of three proximal sgRNAs (sgIL1RN1∼3) activated IL1RN by approximately 6-fold, whereas the three distal sgRNAs (sgIL1RN4∼6) did not induce robust induction. Addition of sgRNA4∼6 to the proximal sgRNAs (sgIL1RN1∼3) did not significantly augment the expression (Figure 2C). These data suggest that gene activation is synergistically promoted by multiple dCas9VP160/sgRNA binding events at the proximal region of the IL1RN promoter. A similar result was obtained with 10 sgRNAs spanning the SOX2 promoter (Figure 2D and 2E). Similarly to IL1RN, expression of single sgRNAs did not yield strong activation of SOX2, while the triple sgRNAs (3∼5, 4∼6, 5∼7, 8∼10) activated SOX2 by more than 4-fold. A 7-fold activation was achieved with sgSOX2-4∼6 and sgSOX2-5∼7, while further distal sgRNAs (sgSOX2-8∼10) or those downstream of transcriptional start sites (TSS) (sgSOX2-1∼2) were less potent. Quintuple sgSOX2-1∼5 had a lower activity than triple sgSOX2 3∼5, suggesting that sgRNAs downstream of TSS (sgSOX2-1∼2) may be detrimental to activation. It is possible that binding of dCas9VP160 to downstream TSS sterically hinders transcription by blocking polymerase, consistent with a previous report on CRISPRi21. To further confirm this observation, we designed six sgRNAs spanning OCT4 promoter, including two _targeting downstream of TSS (sgOCT4-1∼2) (Figure 2F). An 8-fold activation was achieved with sgOCT4-3∼6, albeit all six sgOCT4-1∼6 had a much lower activity than sgOCT4-3∼6, confirming that sgRNAs downstream of TSS (sgSOX2-1∼2) have a negative effect on gene activation (Figure 2G). Thus, in IL1RN, SOX2, and OCT4 promoters, three to five dCas9VP160/sgRNAs binding within 300 bp region upstream of TSS induced the most efficient gene activation.

Figure 2.

dCas9VP160 activates endogenous genes. (A) Protein architecture of dCas9VP160 compared to VP48. (B) Schematic of the human IL1RN promoter region. Locations of transcription start site (TSS) and start codon (ATG) are indicated. Short lines with number indicate _targeting sites of the sgRNAs. (C) Activation of human IL1RN expression in HEK293T cells. Cells were analyzed by qRT-PCR 2 days after transfection with dCas9VP160 and the indicated sgRNAs. (D) Schematic of the human SOX2 promoter region. Locations of TSS and start codon (ATG) are indicated. Short lines with number indicate _targeting sites of sgRNAs. (E) Activation of SOX2. Cells were analyzed by qRT-PCR 2 days after transfection with dCas9VP160 and the indicated sgRNAs. (F) Schematic of the human OCT4 promoter region. Locations of transcription start site (TSS) and start codon (ATG) are indicated. Short lines with number indicate _targeting sites of sgRNAs. (G) Activation of OCT4. Cells transfected with dCas9VP160 and the indicated sgRNAs were analyzed by qRT-PCR 2 days later. sgTetO-mut, negative control sgRNA. Error bars show SD among triplicates.

Multiple exogenous and endogenous genes can be simultaneously activated by CRISPR-on

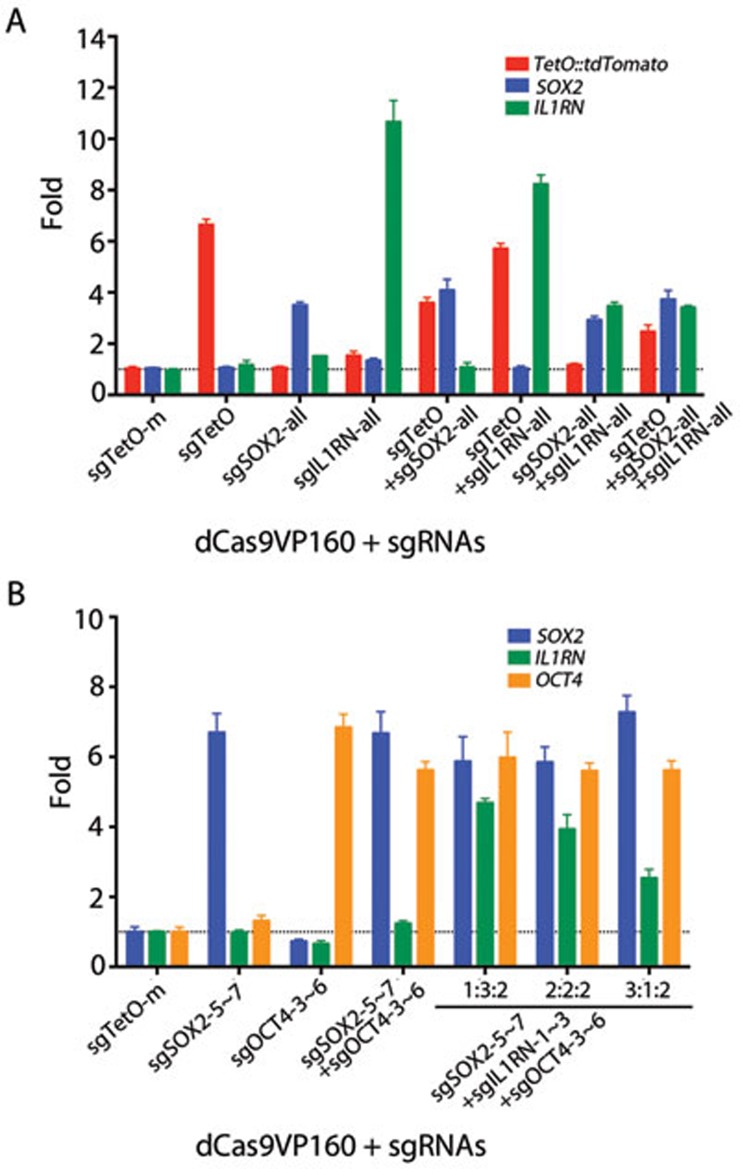

We tested single, double and triple activation of a TetO::tdTomato transgene and the endogenous SOX2 and IL1RN genes (Figure 3A) in HEK293T cells carrying the stably integrated TetO::tdTomato transgene (HEK293T/TetO::tdTomato). Transfection of sgRNAs _targeting the individual promoters (sgTetO for TetO::tdTomato, sgSOX2-1∼10 for SOX2 or sgIL1RN1∼6 for IL1RN) activated the respective genes (TetO: 6.6× SOX2: 3.5× IL1RN: 10.7×) while not affecting expression of the other two genes (Figure 3A). Simultaneous transfection of sgRNAs _targeting two or three promoters activated the corresponding sets of genes (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Multiple exogenous and endogenous genes were simultaneously activated by CRISPR-on. (A) One exogenous and two endogenous genes were simultaneously activated by CRISPR-on. Cells were analyzed by qRT-PCR 2 days after transfection with dCas9VP160 and the indicated sgRNAs. (B) Three endogenous genes, SOX2, IL1RN and OCT4, can be simultaneously activated by dCas9VP160/sgRNAs. Cells were transfected with dCas9VP160 and the indicated sgRNAs and were analyzed by qRT-PCR 2 days after transfection. The Last three sets of bars represent triple activation experiments using sgSOX2, sgOCT4 and sgIL1RN with three different ratios of sgSOX2:sgIL1RN, keeping the amount of sgOCT4 constant, as indicated by numbers above line. sgTetO-mut, negative control sgRNA. Error bars show SD among triplicates.

To test whether the system allows the activation of three different endogenous genes in a dose-dependent manner, we co-transfected HEK293T cells with dCas9VP160 and the most efficient sgRNAs _targeting all three genes (sgIL1RN1∼3 for IL1RN, sgSOX2-5∼7 for _targeting SOX2, and sgOCT4-3∼6 for OCT4) in different ratios (Figure 3B). When sgRNAs _targeting one or two genes were used, only the respective genes were activated. When all sgRNAs _targeting three genes were transfected, albeit in different ratios, we observed robust activation of all three genes (Figure 3B). More significantly, when different ratios of sgRNAs were used _targeting SOX2 and IL1RN while maintaining the OCT4 sgRNAs constant, we observed the predicted change of the ratio of SOX2 and IL1RN expression levels, and the OCT4 expression remained stable (Figure 3B). These results demonstrate that the CRISPR-on system can be robustly used for multiplexed activation of endogenous genes.

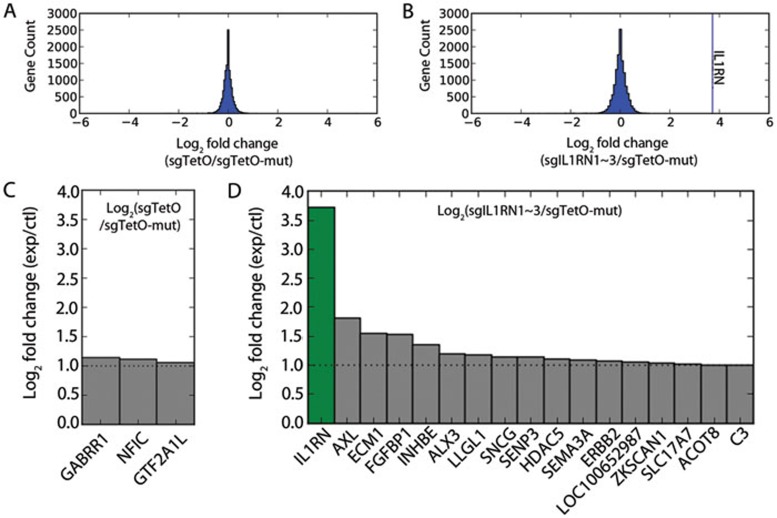

CRISPR-on is highly specific

To test the specificity of CRISPR-on-mediated gene activation, we conducted microarray experiments to compare genome-wide gene expression profiles of cells transfected with dCas9VP160 and specific sgRNAs to cells transfected with dCas9VP160 and sgTetO-mut control sgRNA (Figure 4). While efficiently activating _target genes, CRISPR-on did not cause major perturbations in the transcriptome (Figure 4A and 4B) as only three genes showed an over 2-fold upregulation upon transduction of dCas9VP160/sgTetO (Figure 4C). While CRISPR-on-mediated activation of IL1RN induced the IL1RN _target gene by 13-fold, only 16 other genes showed an about 2-fold increase in expression (Figure 4D). We failed to detect matches of sgRNAs within 2 kb promoters of these genes allowing up to 5 mismatches in the 20 nt _target sequence although we cannot exclude the possibility that dCas9VP160/sgRNA binds to other regions of these loci to activate gene expression. Also, the minor upregulation of these genes may not be direct but due to the over-expression of tdTomato or IL1RN.

Figure 4.

Genome-wide expression analysis of cells transfected with the CRISPR-on system. (A) The histogram showing distribution of Log2 fold changes of gene expression in sample transfected with dCas9VP160/sgTetO over dCas9VP160/sgTetO-mut control. (B) A histogram showing distribution of log2 fold changes of gene expression in cells transfected with dCas9VP160/sgIL1RN1∼3 over dCas9VP160/sgTetO-mut control. Vertical line marks the fold change of the _target gene IL1RN. (C) Column graph showing the Log2 fold changes of genes upregulated by at least 2-fold in cells transfected with dCas9VP160/sgTetO over dCas9VP160/sgTetO-mut. (D) Column graph showing the Log2 fold changes of genes upregulated by more than 2-fold in cells transfected with dCas9VP160/sgIL1RN1∼3 over dCas9VP160/sgTetO-mut. Dotted line indicates the 2-fold cut-off.

Discussion

ATFs are valuable tools for studying gene functions and transcriptional networks. Zinc-fingers and TALE transcription factors have been developed over the recent decades and show promises in both bioengineering and therapeutic applications3,9,10. Here we established CRISPR-on as a novel class of artificial transcription factors based on the CRISPR/Cas system. The major advantage of this system is that only one dCas9 activator is required to activate multiple genes individually or simultaneously and that its DNA binding specificity is determined by sgRNAs, which are designed based on simple RNA/DNA complementarity.

Using CRISPR-on, we demonstrate robust activation of exogenous reporter genes in both human and mouse transformed cells as well as in ES cells. When the system was introduced into one-cell mouse embryos, efficient reporter gene activation was observed, raising the possi-bility of manipulating transcriptional networks in early embryos.

We achieved robust endogenous gene activation using the stronger activation domain VP160. Further optimization of activation domains, such as using different linker sequences, may improve the CRISPR-on activation efficiency even further. The promoter scanning experiments demonstrated that efficient activation of endogenous genes could be achieved by three to five sgRNAs binding within 300 bp region upstream of TSS. Using additional sgRNAs _targeting further upstream or downstream regions did not significantly improve the level of induction. Our data suggest that only a small number of sgRNAs _targeting the proximal promoter are sufficient to activate endogenous genes. While our paper was under review, similar results were reported showing synergistic and robust activation of endogenous genes by proximal binding of dCas9 activators15.

We show here that the CRISPR-on system can be used for the simultaneous induction of at least three different endogenous genes. More significantly, we demonstrated that the stoichiometry of gene induction of multiple genes can be tuned by adjusting the relative amount of their cognate sgRNAs. Simultaneous activation of multiple endogenous genes with defined stoichiometry opens up novel opportunities for systems biology as it allows for the predictable manipulation of transcriptional networks.

Finally, with the ease of design and synthesis, a library of sgRNAs could be generated. When introduced into a cell line constitutively expressing dCas9 activator, gene activation screens mediated by RNA (RNAa) could be achieved. As the specificity components (sgRNA) can be separately designed and constructed from the effector component (Cas fusion proteins), the same library of sgRNAs could be used with different dCas9 fusions (e.g., VP160 domain for transactivation, KRAB domain for transcriptional repression, chromatin modifier domains for specific histone modification) to exert different functions at particular genomic loci.

Materials and Methods

Cloning

A two-step fusion PCR was performed to amplify Cas9 Nickase ORF without stop codon from the pX335 vector (Addgene: 42335), incorporate H840A mutation, EcoRI-AgeI restriction site on the 5′ end as well as an FseI site on the 3′ end (EcoRI-AgeI-dCas9-FseI fragment). The 3× minimal VP16 activation domain coding fragment (VP48) was excised from a vector (Addgene: 20342) containing NLSM2rtTA coding sequence by FseI and EcoRI digestion (FseI-TA-EcoRI fragment). The two fragments were ligated into pCR8/GW/TOPO (Invitrogen) vector digested by EcoRI to generate a gateway compatible dCas9VP48 coding plasmid. The dCas9VP48 coding sequence was subsequently excised and cloned into pX355 vector (Addgene: 42335) by AgeI-EcoRI digestion to replace dCas9 Nickase to create a chimeric vector that expresses both the dCas9VP48 and the sgRNA (dCas9VP48-U6-sgRNA-chimeric). sgRNA spacers were cloned into the BbsI-digested vector by annealing oligos as previously described14. For construction of dCas9VP160, a gBlocks gene fragment containing coding sequence for 10 tandem repeats of VP16 domains separated by Glycine-Serine (GS) linker was ordered from Integrated DNA Technology (IDT) and amplified by PCR primers containing FseI and EcoRI sites to replace VP48 fragment in pCR8-dCas9VP48 to generate pCR8-dCas9VP160. A pmax-DEST gateway destination vector was constructed by replacing GFP coding sequence in pmaxGFP (Clontech) by a gateway destination cassette (Invitrogen). The pCR8-dCas9VP160 vector was then recombined with pmax-DEST via LR clonase-mediated recombination to create pmax-dCas9VP160 expression plasmid. For the endogenous gene experiments, sgRNAs were cloned by oligo cloning method mentioned above into a PBneo-sgRNA expression vector sgRNA _target sequences, oligos for cloning are listed in Supplementary information, Table S1. Plasmids are deposited on Addgene and additional information is available at http://www.crispr-on.org

Culturing and transfection of HeLa, HEK293T and NIH3T3

HeLa, HEK293T and NIH3T3 cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% inactivated FBS, 1% Penn/Strep, 1% Glutamine, 1% non-essential amino acids. Transfection was done using Fugene HD (Promega) using a 2:6 ratio (a total DNA amount of 2 μg and 6 μl of Fugene HD reagent) in 6-well plates. For TetO::tdTomato experiment, 2 μg of the chimeric vector was used. For endogenous gene activation experiments, the U6 promoter-sgRNA-terminator sequence was amplified from the PBneo-sgRNA plasmids, purified by PCR purification kit (QIAGEN), and transfected as linear DNA (1 μg Total sgRNA expressing DNA) with 1 μg of pmax-dCas9VP160 plasmid. When there are multiple sgRNAs for multiple genes, the amount per sgRNA was evenly divided among genes first, then among the sgRNAs _targeting each gene.

Transgene activation in mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs)

mESCs from mice carrying a Dox-inducible Musashi-1 (MSI1) allele in the Col1A1 locus23 were transfected with dCas9VP48 using Xfect mESC transfection reagent (Clontech) or were cultured in mouse ES medium with 2 μg/ml Doxycycline. 48 h later, protein lysates were prepared on ice from cell pellets in SDS-Tris lysis buffer (10% SDS, 10% Glycerol, 0.1 M DTT, 0.12 g/ml Urea) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor tablets (1 tablet/10 ml, Roche) and analyzed by western blot. Blots were probed with primary rabbit anti-MSI1 (Cell Signaling Technologies, #2154), mouse anti-α-Tubulin (Sigma) antibodies. Secondary HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit/anti-mouse IgG were used and visualized with ECL (GE Healthcare).

One-cell embryo injection

All animal procedures were performed according to NIH guidelines and approved by the Committee on Animal Care at MIT. B6D2F1 (C57BL/6 × DBA2) female mice and ICR mouse strains were used as embryo donors and foster mothers, respectively. Super-ovulated female B6D2F1 mice (7-8 weeks old) were mated to B6D2F1 stud males, and fertilized embryos were collected from oviducts. Cas9VP48 plasmid (200 ng/μl), Nanog::EGFP construct (200 ng/μl), and sgRNAs (50 ng/μl for each) were mixed and injected into the cytoplasm of fertilized eggs with well-recognized pronuclei in M2 medium (Sigma). Injected oocytes were cultured in KSOM medium for 96 h to examine their development in vitro. Images of resulting embryos were acquired with an inverted microscope under the same exposure parameters.

Bioinformatics analysis of gene expression and off-_target analysis

Affymetrix U133 Plus 2.0 array was used for microarray gene expression analysis. Gene expression values were processed and normalized using affy package for R25. Microarray data have been deposited onto GEO database with accession number GSE49701. For off-_target analysis, sequences from 2 kb promoters of genes upregulated by two-fold or more were extracted and searched against matches to the 20 nt sgRNA _targeting sequence followed by the NGG PAM sequence allowing up to 5 mismatches.

qRT-PCR expression analysis

Total RNA was isolated using the Rneasy Kit (QIAGEN) and reversed transcribed using the Superscript III First Strand Synthesis kit (Invitrogen). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed in triplicate using the ABI 7900 HT system with FAST SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Gene expression was normalized to GAPDH. Error bars represent the standard deviation (SD) of the mean of triplicate reactions. Primer sequences are included in Supplementary information, Table S2.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jaenisch lab members for helpful discussions on the manuscript. AWC is supported by a Croucher scholarship. RJ is an adviser to Stemgent and a cofounder of Fate Therapeutics. This work was supported by NIH grants HD 045022 and R37CA084198 to RJ.

Footnotes

(Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Cell Research website.)

Supplementary Information

The persistence of CRISPR-on mediated transgene expression.

CRISPR-on activates transgene in mouse cells.

CRISPR-on activated a single-copy transgene in ESCs.

Tunable gene activation can be achieved by titration of sgRNA.

dCas9VP48 with 6 sgRNAs failed to activate the IL1RN gene.

sgRNA designs, DNA _targets, oligos for cloning

qRT-PCR primers

References

- Spitz F, Furlong EE. Transcription factors: from enhancer binding to developmental control. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:613–626. doi: 10.1038/nrg3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blancafort P, Segal DJ, Barbas CF., 3rd Designing transcription factor architectures for drug discovery. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66:1361–1371. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.002758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sera T. Zinc-finger-based artificial transcription factors and their applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61:513–526. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerli RR, Segal DJ, Dreier B, Barbas CF., 3rd Toward controlling gene expression at will: specific regulation of the erbB-2/HER-2 promoter by using polydactyl zinc finger proteins constructed from modular building blocks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14628–14633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerli RR, Dreier B, Barbas CF., 3rd Positive and negative regulation of endogenous genes by designed transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1495–1500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040552697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Cong L, Lodato S, Kosuri S, Church GM, Arlotta P. Efficient construction of sequence-specific TAL effectors for modulating mammalian transcription. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:149–153. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscou MJ, Bogdanove AJ. A simple cipher governs DNA recognition by TAL effectors. Science. 2009;326:1501. doi: 10.1126/science.1178817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boch J, Scholze H, Schornack S, et al. Breaking the code of DNA binding specificity of TAL-type III effectors. Science. 2009;326:1509–1512. doi: 10.1126/science.1178811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeder ML, Linder SJ, Reyon D, et al. Robust, synergistic regulation of human gene expression using TALE activators. Nat Methods. 2013;10:243–245. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Pinera P, Ousterout DG, Brunger JM, et al. Synergistic and tunable human gene activation by combinations of synthetic transcription factors. Nat Methods. 2013;10:239–242. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaya D, Davison M, Barrangou R. CRISPR-Cas systems in bacteria and archaea: versatile small RNAs for adaptive defense and regulation. Annu Rev Genet. 2011;45:273–297. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedenheft B, Sternberg SH, Doudna JA. RNA-guided genetic silencing systems in bacteria and archaea. Nature. 2012;482:331–338. doi: 10.1038/nature10886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337:816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, et al. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinek M, East A, Cheng A, Lin S, Ma E, Doudna J. RNA-programmed genome editing in human cells. Elife. 2013;2:e00471. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Yang H, Shivalila CS, et al. One-step generation of mice carrying mutations in multiple genes by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Cell. 2013;153:910–918. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W, Bikard D, Cox D, Zhang F, Marraffini LA. RNA-guided editing of bacterial genomes using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:233–239. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang WY, Fu Y, Reyon D, et al. Efficient genome editing in zebrafish using a CRISPR-Cas system. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:227–229. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu PD, Scott DA, Weinstein JA, et al. DNA _targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases Nat Biotechnol 2013. Jul 21. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Qi LS, Larson MH, Gilbert LA, et al. Repurposing CRISPR as an RNA-guided platform for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Cell. 2013;152:1173–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert LA, Larson MH, Morsut L, et al. CRISPR-mediated modular RNA-guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. Cell. 2013;154:442–451. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharas MG, Lengner CJ, Al-Shahrour F, et al. Musashi-2 regulates normal hematopoiesis and promotes aggressive myeloid leukemia. Nat Med. 2010;16:903–908. doi: 10.1038/nm.2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva J, Nichols J, Theunissen TW, et al. Nanog is the gateway to the pluripotent ground state. Cell. 2009;138:722–737. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier L, Cope L, Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA. affy--analysis of Affymetrix GeneChip data at the probe level. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:307–315. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The persistence of CRISPR-on mediated transgene expression.

CRISPR-on activates transgene in mouse cells.

CRISPR-on activated a single-copy transgene in ESCs.

Tunable gene activation can be achieved by titration of sgRNA.

dCas9VP48 with 6 sgRNAs failed to activate the IL1RN gene.

sgRNA designs, DNA _targets, oligos for cloning

qRT-PCR primers