Publisher's Note: There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

Key Points

FLT3-ITD mutations suppress ceramide generation, and FLT3-ITD inhibition mediates ceramide-dependent mitophagy, leading to AML cell death.

Alteration of mitochondrial ceramide prevents mitophagy, resulting in resistance to FLT3-ITD inhibition which is attenuated by LCL-461.

Abstract

Signaling pathways regulated by mutant Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3)–internal tandem duplication (ITD), which mediate resistance to acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cell death, are poorly understood. Here, we reveal that pro-cell death lipid ceramide generation is suppressed by FLT3-ITD signaling. Molecular or pharmacologic inhibition of FLT3-ITD reactivated ceramide synthesis, selectively inducing mitophagy and AML cell death. Mechanistically, FLT3-ITD _targeting induced ceramide accumulation on the outer mitochondrial membrane, which then directly bound autophagy-inducing light chain 3 (LC3), involving its I35 and F52 residues, to recruit autophagosomes for execution of lethal mitophagy. Short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-mediated knockdown of LC3 prevented AML cell death in response to FLT3-ITD inhibition by crenolanib, which was restored by wild-type (WT)-LC3, but not mutants of LC3 with altered ceramide binding (I35A-LC3 or F52A-LC3). Mitochondrial ceramide accumulation and lethal mitophagy induction in response to FLT3-ITD _targeting was mediated by dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) activation via inhibition of protein kinase A–regulated S637 phosphorylation, resulting in mitochondrial fission. Inhibition of Drp1 prevented ceramide-dependent lethal mitophagy, and reconstitution of WT-Drp1 or phospho-null S637A-Drp1 but not its inactive phospho-mimic mutant (S637D-Drp1), restored mitochondrial fission and mitophagy in response to crenolanib in FLT3-ITD+ AML cells expressing stable shRNA against endogenous Drp1. Moreover, activating FLT3-ITD signaling in crenolanib-resistant AML cells suppressed ceramide-dependent mitophagy and prevented cell death. FLT3-ITD+ AML drug resistance is attenuated by LCL-461, a mitochondria-_targeted ceramide analog drug, in vivo, which also induced lethal mitophagy in human AML blasts with clinically relevant FLT3 mutations. Thus, these data reveal a novel mechanism which regulates AML cell death by ceramide-dependent mitophagy in response to FLT3-ITD _targeting.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) has poor prognosis1 with a 5-year survival rate of only 20%. Activating mutations in Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) are present in one-third of adult AML patients.2 FLT3 is a membrane-bound receptor tyrosine kinase,3 which activates mitogenic downstream signaling pathways such as Ras/MAPK, JAK/phosphorylated Stat 5 (p-Stat5), and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase–Akt.4,5 The most common activating FLT3 mutation is an internal tandem duplication (ITD) in the juxtamembrane domain (FLT3-ITD).6,7 FLT3-ITD inhibitors, such as sorafenib, AC220, and crenolanib, showed efficacy for therapy in preclinical models of AML.8-10 However, clinical trials using FLT3-ITD inhibitors have shown limited success because of the development of drug resistance.11 Thus, determining novel mechanisms that control cell death in response to FLT3-ITD inhibitors in AML for the development of mechanism-based therapeutic strategies to overcome drug resistance is important.

Mitophagy is a cellular process for the degradation of mitochondria by the autophagic machinery.12-14 The conjugation of light-chain 3 (LC3) to phosphatidylethanolamine (LC3-PE or LC3-II) promotes the formation of double-membrane autophagosomes, which engulf/digest mitochondria using lysosomal enzymes. One of the key regulators of mitophagy is dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1), which induces mitochondrial fission.15,16 Upon its activation, Drp1, a cytosolic GTPase, translocates to mitochondria where it forms dimers/oligomers,16,17 inducing mitochondrial fission. Drp1 is activated by calcineurin-dependent dephosphorylation or inactivated by protein kinase A (PKA)–dependent phosphorylation at S637.16,18 Drp1 can also be activated by cyclin B1-CDK–dependent phosphorylation at S616.18 Even though recent studies suggest that _targeting cancer cell mitochondria is a promising therapeutic strategy, the role of mitophagy-mediated cell death in the response of AML to FLT3-_targeted therapy is still unknown.

Ceramide is a bioactive sphingolipid that is generated in response to various chemotherapeutic agents including tyrosine kinase inhibitors.19 Ceramide is synthesized de novo by the action of ceramide synthases 1-6 (CerS1-6), which selectively generate ceramides with various fatty acid chain lengths.20 For example, CerS1 generates C18-ceramide, whereas CerS6 generates mainly C16-ceramide.21,22 CerS1-generated C18-ceramide induces cancer cell death and is emerging as a tumor suppressor lipid.23-25 Ceramide plays a key role in the regulation of autophagy.26-29 However, any mechanistic link between FLT3 signaling and ceramide metabolism for the regulation of mitophagy-dependent cell death (lethal mitophagy) has not been described previously. Thus, we set out studies to determine the roles and mechanisms by which FLT3-ITD signaling regulates ceramide metabolism and cell death via modulating ceramide-dependent mitophagy in AML.

Methods and materials

Cell lines and culture conditions

MV4-11 (ATCC), Molm-14 (P.B.), TF-1 (ATCC), and Ba/f3 (M.A.) AML cell lines were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (ATCC) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologics), 1% penicillin and streptomycin, and prophylactic antimycoplasma reagent. The media for TF-1 was supplemented with interleukin-3. Primary patient CD34+ AML blasts or normal human bone marrow cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 with 20% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin and streptomycin, and 1% gentamycin. All cells were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Ultrastructure analysis using transmission electron microscopy

AML cells were fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde (wt/vol) in 0.1 M cacodylate following removal of culture medium. After postfixation in 2% (vol/vol) osmium tetroxide, specimens were embedded in Epon 812, and sections were cut orthogonally to the cell monolayer with a diamond knife. Thin sections were visualized in a JEOL 1010 transmission electron microscope.

Cell fractionation

Cells were sheared using a 25-G needle. After centrifuging to obtain the nuclear fraction, samples were centrifuged at 10 000g to pellet down the mitochondrial fraction. Western blotting was used to detect the purity of the fractions with Tom20 as a mitochondrial marker and actin as a cytosolic marker.

Synthesis of LCL-461

(2S, 3R, 4E)-2-N-octadecanoyl-14-(1′-pyridinium)-sphingosine bromide, (D-e-C18-Ceramide-14′-pyridinium bromide), was synthesized by Lipidomics Shared Resource, Synthetic Unit, Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), as described.30,31

High-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry analysis of sphingolipids

Lipid extractions and analyses were performed by Lipidomics Shared Resource, Analytical Unit, MUSC. Briefly, cells were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer. Further preparation of samples and advanced analyses of endogenous bioactive sphingolipids were performed on the ThermoFisher TSQ Quantum liquid chromatography/triple-stage quadrupole mass spectrometer system, operating in a multiple reaction monitoring positive ionization mode, as previously described.32 Lipid levels were normalized to the level of protein present in samples (picomoles per milligram of protein).

Purification of autophagosomes

The plasma membrane was disrupted mechanically using a 20-G syringe in a detergent-free buffer. After pelleting down the nucleus and nonlysed cells, the remaining organelles were incubated with agarose beads and LC3B antibody recognizing the N terminus of LC3B. Agar beads were washed several times and then resuspended in sodium dodecyl sulfate loading buffer for western blot analysis.

NSG AML mouse model

Animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at MUSC. Male NSG mice (NOD.Cg-PrkdcScidI12rgtm1Wj1/SzJ), at the age of 8 to 12 weeks, weighing 18 to 22 g, were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. The mice were injected with 5 × 106 MV4-11 cells via the lateral tail vein. Mice harboring AML xenografts received intraperitoneal injections of either vehicle (5% dimethyl sulfoxide), 15 mg/kg crenolanib, or 15 mg/kg LCL-461. At the end of the experiments, liver, spleen, and bone marrow were harvested.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

Harvested bone marrow was incubated with ACK buffer to lyse red blood cells. This was followed by incubation of the cells with phycoerythrin–human CD45 (hCD45) antibody for 30 minutes. The cells were resuspended in flow buffer with DNase and EDTA and transferred to flow tubes. A FACSAria IIu cell sorter was used to sort hCD45+ cells from the rest of the bone marrow cells.

Statistical analysis

Data were reported as mean ± standard deviation or standard error as indicated. The mean values were compared using the 2-sided Student t test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) and P values of <.05 were considered significant.

Results

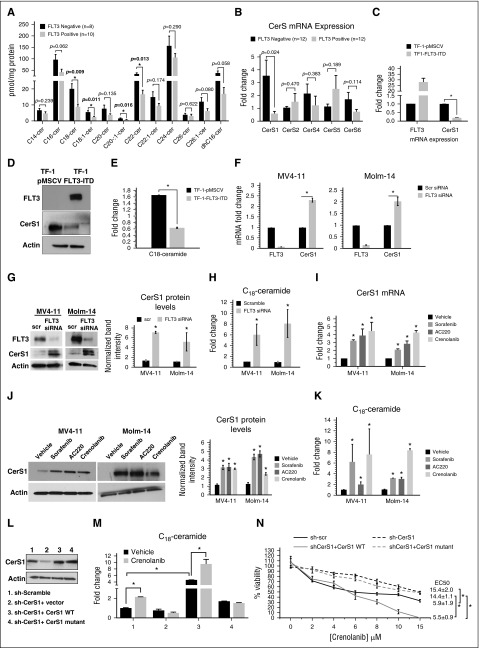

FLT3 activation suppresses CerS1/C18-ceramide metabolism

To determine whether FLT3-ITD signaling regulates ceramide metabolism, we measured the levels of ceramides by mass spectrometry (MS) in FLT3-ITD+ vs FLT3− AML samples obtained from patients. Data revealed that FLT3+ AML cells contain lower levels of C18-, C18:1-, C20:1-, and C22-ceramide compared with FLT3− AML cells (Figure 1A). In addition, CerS1 was lower in FLT3+ AML cells compared with FLT− AML cells (P = .024), whereas CerS2, CerS4, CerS5, or CerS6 messenger RNAs (mRNAs) were comparable between the 2 groups of AML patients (Figure 1B). Thus, these data suggest that a FLT3+ mutation status in human AML blasts is associated with a decreased level of CerS1-generated C18-ceramide.

Figure 1.

Reactivation of CerS1-C18-ceramide axis is required for the response of AML cells to FLT3-_targeted therapy. (A) MS high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-MS-MS analysis for the different ceramide species in FLT3+ vs FLT3− CD34+ AML blasts obtained from bone marrow of AML patients. (B) Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) measurement of CerSs mRNA expression in FLT3+ vs FLT3− CD34+ AML blasts obtained from bone marrow of AML patients. (C) CerS1 mRNA in TF-1 cells transfected with FLT3-ITD overexpression vector. (D) Western blot for CerS1 protein in TF-1 cells transfected with FLT3-ITD overexpression vector. (E) HPLC-MS-MS measurement of C18-ceramide in TF-1 cells transfected with FLT3-ITD overexpression vector. (F) qPCR measuring CerS1 mRNA in cells transfected with FLT3 small interfering RNA (siRNA). (G) qPCR measuring CerS1 mRNA in cells treated with FLT3 pharmacological inhibitors. (H) Western blotting measuring CerS1 protein in cells transfected with FLT3 siRNA. (I) Western blotting measuring CerS1 protein in cells treated with FLT3 pharmacological inhibitors. (J) HPLC-MS-MS measuring C18-ceramide in cells transfected with FLT3 siRNA. (K) HPLC-MS-MS measuring C18-ceramide in cells treated with FLT3 pharmacological inhibitors. (L) Western blot to detect CerS1 protein in sh-CerS1 cells reconstituted with CerS1 WT or CerS1-H138A catalytically inactive mutant. (M) HPLC-MS-MS measurement of C18-cermide in crenolanib-treated cells transfected with CerS1 WT or CerS1-H138A catalytically inactive mutant. (N) Percentage of viability measured using MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-dimethyltetrazolium bromide) assay for sh-scr, sh-CerS1, sh-CerS1+CerS1 WT, and sh-CerS1+CerS1 H1338A mutant, treated with crenolanib. Values indicate mean ± standard deviation (SD) of n = 3 independent experiments. *P value of <.05 using the 2-sided Student t test.

We then measured CerS1 and ceramide in FLT3-ITD+ MV4-11 and Molm-14 human AML cells. CerS1 mRNA, protein, and C18-ceramide were significantly decreased in MV4-11 and Molm-14 cells compared with CD34+ nonleukemic human hematopoietic cells and FLT3− TF-1 AML cells (supplemental Figure 1A-C, available on the Blood Web site). Ectopic expression of FLT3-ITD in TF-1 cells decreased CerS1 mRNA, protein, and C18-ceramide compared with vector-transfected controls (Figure 1C-E). However, overexpression of FLT3-ITD had no detectable effect on CerS2-6 in TF-1 cells (supplemental Figure 1D-E). Thus, these data suggest that activation of FLT3-ITD signaling selectively downregulates the pro-cell death CerS1/C18-ceramide axis.

Inhibition of FLT3 reactivates pro-cell death CerS1/C18-ceramide generation

Next, we determined whether inhibition of FLT3 signaling results in reactivating CerS1 and ceramide generation in MV4-11 and Molm-14 cells. Knocking down of FLT3-ITD using pooled siRNAs increased CerS1 mRNA, protein, and C18-ceramide, compared with scrambled siRNA transfected control (Figure 1F-H). Similarly, pharmacological inhibition of FLT3 using sorafenib, AC220, or crenolanib increased the levels of CerS1 mRNA, protein, and C18-ceramide levels compared with vehicle-treated controls (Figure 1I-K). Molecular or pharmacological inhibition of FLT3-ITD signaling had no effect on CerS2-6 (supplemental Figure 2A-F). Thus, these data suggest that _targeting FLT3-ITD selectively reactivates CerS1/C18-ceramide synthesis.

We then assessed whether the reactivation of the CerS1/C18-ceramide axis is involved in the induction of cell death in response to FLT3-ITD _targeting in AML cells. Inhibition of CerS activity by fumonisin B1 (FB-1) prevented the generation of C18-ceramide and cell death by FLT3 inhibitors (supplemental Figure 3A-B). Moreover, siRNA-mediated knockdown of CerS1, but not CerS4 or CerS6, resulted in resistance to cell death in response to FLT3-ITD inhibition by sorafenib or crenolanib (supplemental Figure 3C-G). Similarly, MV4-11 cells stably transfected with sh-CerS1 were protected from cell death in response to FLT3 knockdown or FLT3-ITD inhibitors crenolanib, sorafenib, or AC220 (supplemental Figures 1F and 3H-K). Reconstitution of CerS1-wild type (WT), but not catalytically inactive CerS1-H138A, resensitized sh-CerS1–expressing MV4-11 cells to crenolanib (Figure 1L-N). Thus, these data suggest that reactivation of CerS1/C18-ceramide generation plays a key role in the induction of cell death in response to FLT3-ITD inhibition in AML cells.

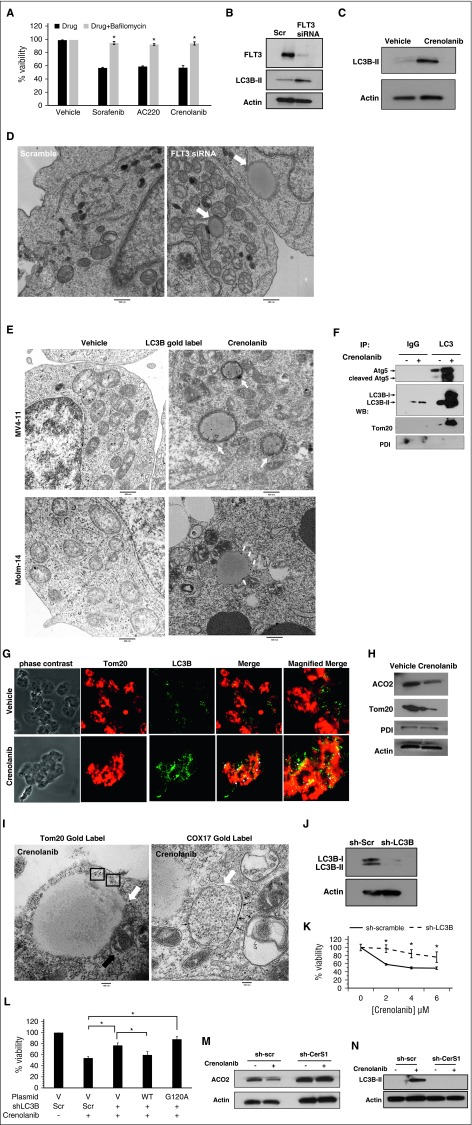

_targeting FLT3-ITD mediates AML cell death by inducing CerS1/C18-ceramide–dependent mitophagy

To determine the mechanism of cell death in response to FLT3-ITD inhibition, we measured the effects of FLT3-ITD inhibitors on apoptosis, necroptosis, and autophagy in MV4-11 cells. Treatment with FLT3-ITD inhibitors failed to induce poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 cleavage or lactate dehydrogenase release, events that typically occur during apoptosis and necrosis, respectively (supplemental Figure 4A-B). In addition, pretreatment with zVAD, pan-caspase inhibitor, or necrostatin-1, necroptosis inhibitor, had no effect on AML cell viability in response to FLT3-ITD inhibitors (supplemental Figure 4C-D). However, pretreatment with bafilomycin, inhibitor of lysosomal flux and autophagy, protected AML cells from death by FLT3-ITD inhibitors (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Inhibition of FLT3 induces mitophagy. (A) MV4-11 cells are pretreated with bafilomycin, inhibitor of autophagy, followed by treatment with 10 μM sorafenib, 10 μM AC220, or 5 μM crenolanib for 24 hours. Cell viability is measured using the MTT assay. (B) Western blot to detect LC3B-I (top band) and LC3B-II (bottom band) in MV4-11 cells transfected with FLT3 siRNA. (C) Western blot measuring LC3B in cells treated with crenolanib FLT3 inhibitor. (D) MV4-11 cells were transfected with FLT3 siRNA and visualized for morphology. White arrows indicate autophagosomes. (E) MV4-11 or Molm-14 cells were treated with crenolanib and gold labeled with LC3B. White arrows indicate LC3B immune-gold label in autophagosomal structures. (F) Disrupted cells were incubated with agarose beads and LC3B antibody to pull down autophagosomes followed by western blotting for Atg5, LC3B, and Tom20 in purified autophagosomes. (G) Confocal microscopy for treated cells dual labeled with LC3B antibody and Tom20 mitochondrial marker. (H) Western blotting measuring ACO2, Tom20, and PDI in crenolanib-treated cells. (I) Electron microscopy visualization of autophagosomes in crenolanib-treated cells gold labeled with Tom20 or COX-17. Squares or small black arrows indicate gold label. White arrow indicates autophagosomes. (J) Western blot analysis for LC3B in sh-scr and sh-LC3B stable-transfected cells. (K) Percentage of viability measured using the MTT assay in sh-LC3B cells treated with different doses of crenolanib for 24 hours. (L) Percentage of nonviable cells measured using MTT assay in sh-scr, sh-LC3B, sh-LC3B+WTLC3B, and sh-LC3B+LC3BG120A. (M-N) Western blot to measure ACO2 and LC3B-II in crenolanib-treated sh-scr vs sh-CerS1 cells. *P value of <.05 using the 2-sided Student t test. All images are representative of at least 2 independent experiments.

We then examined whether inhibition of FLT3-ITD induces ceramide-dependent autophagy. _targeting FLT3-ITD increased the formation of Cyto-ID+ autophagosomes, LC3 lipidation/activation, and the formation of double-membrane autophagosomes positive for LC3 as visualized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) using gold-labeled anti-LC3B antibody (Figure 2B-E; supplemental Figure 4E-H). TEM showed that autophagosomes were interacting/engulfing mitochondria, suggestive of mitophagy (Figure 2D). Indeed, we detected an increase in the colocalization of LC3B (autophagosomal marker) with Tom20 (mitochondrial marker) in response to FLT3-ITD inhibition using immunofluorescence (Figure 2G). In addition, we detected a decrease in mitochondrial matrix protein aconitase hydratase 2 (ACO2), whereas no change was detected in the endoplasmic reticulum luminal protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) in crenolanib-treated cells compared with controls (Figure 2H), supporting mitophagy induction. We then purified LC3B+ autophagosomes from cells treated with vehicle or crenolanib using immunoprecipitation with anti-LC3B antibody. Purification of autophagosomes was confirmed by detection of LC3B and Atg5 proteins in fractions obtained from crenolanib-treated cells compared with vehicle-treated controls. Autophagosome-enriched fractions contained mitochondrial protein Tom20, but not PDI (Figure 2F). We also detected increased immunogold staining for mitochondrial markers Tom20 or COX-17 in autophagosomal membranes by TEM in response to FLT3-ITD inhibition (Figure 2I). These data support that _targeting FLT3-ITD induces mitophagy.

siRNA knockdown of autophagy proteins LC3B, Beclin-1, or Atg5 protected AML cell death in response to crenolanib (supplemental Figure 4I-K). In addition, overexpressing WT-LC3B, but not inactive mutant LC3B-G120A, resensitized sh-LC3B cells to crenolanib-induced cell death compared with vector-transfected controls (Figure 2J-L). Moreover, short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-dependent CerS1 knockdown or its inhibition by FB-1 prevented LC3 lipidation/activation and protected the degradation of mitochondrial matrix protein ACO2 in response to crenolanib (Figure 2M-N; supplemental Figure 4O). Thus, these data suggest that _targeting FLT3-ITD induces AML cell death via CerS1/C18-ceramide–mediated mitophagy.

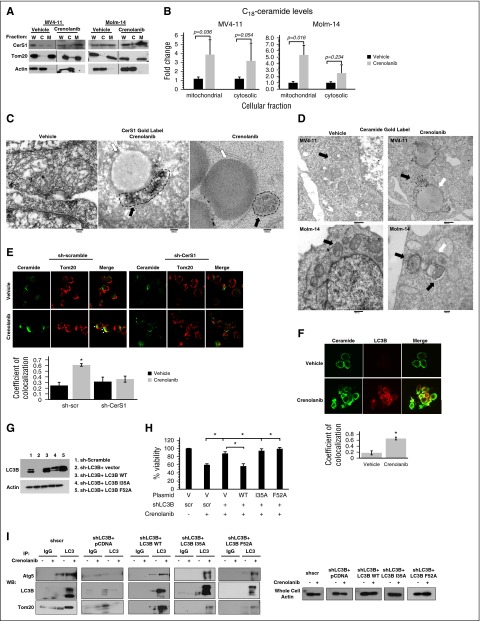

CerS1 and C18-ceramide localize to mitochondria upon inhibition of FLT3-ITD

Enrichment of cytosolic vs mitochondrial fractions obtained from MV4-11 cells revealed that inhibition of FLT3-ITD by crenolanib induced mitochondrial localization of the CerS1 enzyme (Figure 3A). This was consistent with increased generation/accumulation of C18-ceramide in mitochondria-enriched subcellular fractions in response to FLT3-ITD inhibition as measured using MS (Figure 3B). We also detected increased colocalization between ceramide and Tom20 following crenolanib treatment, which was prevented in sh-CerS1–transfected MV4-11 cells (Figure 3E). In addition, TEM gold-immunolabeling images showed enriched localization of CerS1 or ceramide in mitochondria interacting with autophagosomes upon FLT3-ITD inhibition compared with vehicle-treated controls (Figure 3C-D). Thus, these data suggest that inhibition of FLT3-ITD induces CerS1/ceramide localization in AML mitochondria.

Figure 3.

C18-ceramide accumulates in mitochondria and binds to LC3B to recruit autophagosomes to mitochondria. (A) MV4-11 or Molm-14 cells are fractionated to purify mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions followed by western blot to detect CerS1 in the purified fractions. Tom20 was used as a marker for mitochondrial fraction (M) and actin was used as a marker for cytosolic fraction (C); (B) HPLC-MS-MS measurement of C18-ceramide in mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions. (C) Electron microscopy (EM) visualization of MV4-11 cells treated with crenolanib and gold labeled with CerS1 antibody. Black arrows indicate gold label in mitochondria and white arrows indicate autophagosome. (D) EM visualization of MV4-11 or Molm-14 cells treated with crenolanib and gold labeled with ceramide antibody. Black arrows indicate gold label in mitochondria and white arrows indicate autophagosomes. (E) Treated sh-scr and sh-CerS1 cells are dual labeled with ceramide antibody and Tom20 mitochondrial marker and visualized using confocal microscopy. White arrows indicate colocalization. The quantification of ceramide-Tom20 colocalization from confocal microscopy was performed using the ImageJ Fiji software (right panel). (F) Crenolanib-treated MV4-11 cells are dual labeled with ceramide antibody and LC3B autophagosomal marker and visualized using confocal microscopy. White arrows indicate colocalization. (G) Western blot to detect LC3B protein in sh-LC3B cells reconstituted with LC3B WT or LC3B mutants (I35A and F52A) that cannot bind ceramide. (H) Percentage of viability measured using MTT assay for sh-scr, sh-LC3B, sh-LC3B+LC3B WT, sh-LC3B+LC3B I35A, and sh-LC3B+LC3BF52A, treated with crenolanib for 24 hours. (I) Autophagosomes were purified from vehicle or crenolanib treated in sh-LC3B cells reconstituted with LC3B WT or LC3B mutants (I35A and F52A) that cannot bind ceramide. This was followed by a western blot to detect autophagosome markers (Atg5 or LC3B) and Tom20 mitochondria marker. Values indicate mean ± SD of n = 3 independent experiments. *P value of <.05 using the 2-sided Student t test. C, cytosolic fraction; M, mitochondrial fraction; W, whole cell.

Mitochondrial ceramide binds LC3B to recruit autophagosomes for the execution of lethal mitophagy

To address the mechanism by which mitochondrial ceramide mediates lethal mitophagy in response to FLT3-ITD _targeting, we examined whether direct binding between C18-ceramide and LC3B is involved in this process. Ceramide binding to LC3B involves I35 and F52 residues of LC3B.29 Indeed, confocal microscopy revealed increased colocalization between ceramide and LC3B in response to FLT3 inhibition (Figure 3F). Reconstitution with LC3B-WT, but not LC3B mutants with reduced ceramide binding (I35A or F52A), restored mitophagosome formation and cell death in sh-LC3B cells in response to FLT3 inhibition compared with vector-transfected controls (Figure 3G-I). Thus, these data suggest that the association between mitochondrial C18-ceramide and LC3B-II is required for mitophagosome formation for the execution of lethal mitophagy in response to FLT3-ITD inhibition.

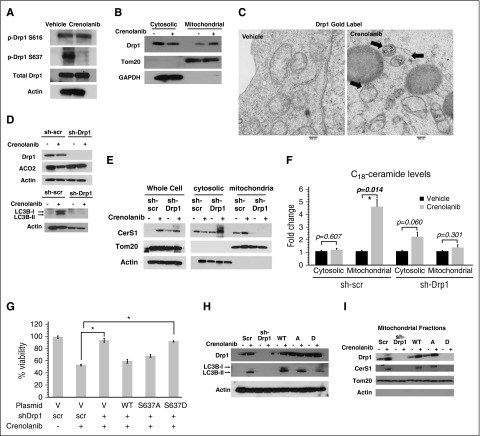

Drp1-mediated fission is required for CerS1/C18-ceramide mitochondrial localization and lethal mitophagy in response to FLT3-ITD inhibition

Drp1 is a key regulator of mitochondrial fission and mitophagy.33 Inhibiting FLT3-ITD using siRNA or crenolanib increased Drp1 protein dimers and the number of mitochondria undergoing fission compared with controls (Figure 4A; supplemental Figure 5A). This was concomitant with dephosphorylation/activation of Drp1-S637 without affecting its phosphorylation at S616 in response to crenolanib (Figure 4A). Similarly, _targeting FLT3-ITD increased Drp1 accumulation in mitochondria detected by subcellular fractionation and TEM compared with vehicle-treated control MV4-11 cells (Figure 4B-C). Thus, these data suggest that FLT3 _targeting results in dephosphorylation/activation of Drp1-S637 and increased mitochondrial fission.

Figure 4.

FLT3 inhibition–induced ceramide-mediated lethal mitophagy requires Drp1 S637 dephosphorylation and activation. (A) Western blot measuring p-Drp1 S616 and p-Drp1 S637 in cells treated with FLT3 inhibitor for 6 hours. (B) Western blot detecting Drp1 in mitochondrial and cytosolic fraction after 6 hours of crenolanib treatment. Tom20 was used as a marker for mitochondria and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a marker for cytosolic fraction. (C) EM visualization of crenolanib-treated cells gold labeled with Drp1. (D) ACO2 and LC3B in crenolanib-treated sh-scr vs sh-Drp1 cells. (E) Western blot to measure CerS1 in mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions obtained from crenolanib-treated sh-scr and sh-Drp1 cells. (F) C18-ceramide measured by MS HPLC-MS-MS in mitochondrial and cytosolic fraction purified from crenolanib-treated sh-scr and sh-Drp1 cells. (G) Percentage of viability measured using the MTT assay in sh-scr, sh-Drp1, sh-Drp1+Drp1WT, sh-Drp1+Drp1S637A, and sh-Drp1+Drp1S637D cells in response to 24-hour treatment with 5 μM crenolanib. (H) Western blot to detect LC3B in sh-Drp1 cells reconstituted with Drp1S637A (A) or Drp1S637D (D) mutants. (I) Western blot to detect CerS1 in purified mitochondrial fractions from sh-Drp1 cells reconstituted with Drp1 S637A (A) or Drp1 S637D (D) mutants. Tom20 and actin levels were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Values indicate mean ± SD of n = 3 independent experiments. *P value of <.05 using the 2-sided Student t test.

We then determined the role of Drp1 in ceramide-dependent lethal mitophagy induced by FLT3-ITD inhibition. The data revealed that inhibition of Drp1 using pooled siRNAs or mdivi-1, a pharmacologic inhibitor of Drp1, protected MV4-11 cells from crenolanib-induced cell death (supplemental Figure 5B-G). In addition, shRNA-mediated Drp1 knockdown in MV4-11 cells prevented mitochondrial fission, LC3B lipidation, ACO2 degradation, and CerS1/C18-ceramide mitochondrial localization compared with controls (Figure 4D-F; supplemental Figure 5H-I). Reconstitution of WT-Drp1 in sh-Drp1–expressing MV4-11 cells increased mitochondrial fission, restored mitochondrial CerS1 localization or LC3B lipidation, and resensitized cells to crenolanib-induced cell death compared with vector-transfected controls (Figure 4G-I; supplemental Figure 5I). Ectopic expression of phospho-null Drp1-S637A, but not phospho-mimetic Drp1-S637D, mutant also restored mitochondrial fission and mitophagy in MV4-11 cells, which stably express sh-Drp1 in response to crenolanib compared with vector-transfected controls (Figure 4G-I). Thus, these data suggest that decreased phosphorylation and/or dephosphorylation-dependent activation of Drp1 at S637 plays a key role in inducing mitochondrial fission and mitochondrial localization of CerS1/C18-ceramide for the induction of lethal mitophagy in response to FLT3-ITD _targeting.

Activation of Drp1 by S637 dephosphorylation can be due to increased calcineurin phosphatase activity or decreased PKA activity. Recent studies showed that _targeting FLT3-ITD results in inhibition of both PKA and calcineurin.34,35 Thus, we hypothesized that Drp1-S637 dephosphorylation should be due to inhibition of PKA, as calcineurin inhibition should have increased S637 phosphorylation in response to FLT3-ITD _targeting. In fact, inhibition of PKA using HA-89 decreased p-Drp1-S637 levels (supplemental Figure 5J). Activation of PKA by bromo-cAMP restored p-Drp1-S637 levels in crenolanib-treated cells compared with vehicle-treated controls. Moreover, activation of PKA prevented CerS1 mitochondrial localization and induction of mitophagy in response to crenolanib (supplemental Figure 5K-M). However, activation of PKA did not prevent mitophagy induction in crenolanib-treated cells expressing phospho-null Drp1-S637A mutant (supplemental Figure 5L). Activation of PKA by bromo-cAMP inhibited mitochondrial localization of CerS1 in response to crenolanib (supplemental Figure 5M). Thus, these data suggest that inhibition of PKA in response to FLT3-ITD _targeting results in activation of Drp1 by reduced Drp1-S637 phosphorylation, resulting in induced mitochondrial fission and ceramide-mediated lethal mitophagy.

_targeting mitochondria by LCL-461 overcomes resistance to FLT3-ITD inhibitor crenolanib

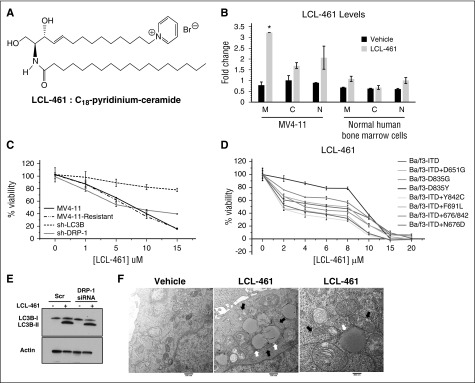

We next hypothesized that direct activation of lethal mitophagy by exogenous ceramide, which is _targeted to mitochondria, should provide a novel AML therapeutic strategy that can bypass FLT3-ITD signaling and help overcome resistance to FLT3-ITD inhibitor crenolanib. To test this hypothesis, we used LCL-461, (S2,3R)-2-N-octadecanoyl-14-(1′-pyridinium)-sphingosine-bromide, also referred to as d-e-C18-pyridinium-ceramide (Figure 5A). LCL-461 contains a pyridinium ring attached to the sphingoid base, which increases the solubility and _targets ceramide to selectively accumulate in negatively charged cancer cell mitochondria.36-38 We detected LCL-461 accumulation in mitochondria-enriched fractions of MV4-11 cells and minimally in nuclear fractions using mass spectrometry (Figure 5B). However, LCL-461 was undetectable in mitochondrial fractions isolated from nonleukemic hematopoietic LCL-461–treated cells (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

LCL-461 accumulates in mitochondria to induce LC3B-dependent lethal mitophagy regardless of FLT3 mutation status. (A) Chemical structure of LCL-461 or C18-pyridinium ceramide. (B) MS detection of LCL-461 in mitochondrial, cytosolic, and nuclear fractions in vehicle and LCL-461–treated MV4-11 or normal human bone marrow cells. (C) Percentage of viability measured using MTT assay in MV4-11, MV4-11–resistant, sh-LC3B, and sh-Drp1 cells in response to LCL-461. (D) Percentage of viability measured using the MTT assay of AML cell lines with different FLT3 mutations in response to LCL-461. (E) Western blot showing LC3B in LCL-461–treated cells transfected with scr or Drp1 siRNA. (F) EM visualization of mitophagosomes induced by LCL-461 treatment in MV4-11 cells treated with 5 μM LCL-461. White arrows indicate autophagosomes and black arrows indicate mitochondria. Values indicate mean ± SD of n = 3. *P value of <.05 using the 2-sided Student t test.

Interestingly, LCL-461 induced cell death in a dose-dependent manner against a variety of Ba/f3 cells stably expressing clinically relevant FLT3 mutants (Figure 5C-D). Next, we generated drug-resistant cells (MV4-11-R) by chronic crenolanib exposure using increasing concentrations. MV4-11-R cells treated with crenolanib failed to increase C18-ceramide generation and exhibited twofold resistance to cell death compared with parental MV4-11 cells (supplemental Figure 6A-C). However, both MV4-11 and MV4-11-R responded similarly to LCL-461–mediated cell death (Figure 5C). Both crenolanib and LCL461 exhibited similar cytotoxicity in Ba/f3 cells expressing various clinically relevant FLT3 mutants, including ITD, ITD + D651G, D835G, D835Y, ITD + Y842C, ITD + F691L, ITD + 676/842, ITD + N676D (Figure 5D; supplemental Figure 6D). Moreover, LCL-461, but not exogenous C18-ceramide without pyridinium conjugation, induced mitophagy in MV4-11, MV4-11R, and Molm-14 cells compared with vehicle-treated controls (Figure 5E-F; supplemental Figure 6E-F). Importantly, LCL-461 exhibited minimal cytotoxicity in nonleukemic human hematopoietic bone marrow cells (supplemental Figure 6G). In addition, shRNA knockdown of LC3B in MV4-11-R cells protected cell death in response to LCL-461 compared with sh-scr–transfected controls (Figure 5C). These data suggest that _targeting mitochondria by LCL461 bypasses upstream FLT3-ITD resistance signaling and induces lethal mitophagy.

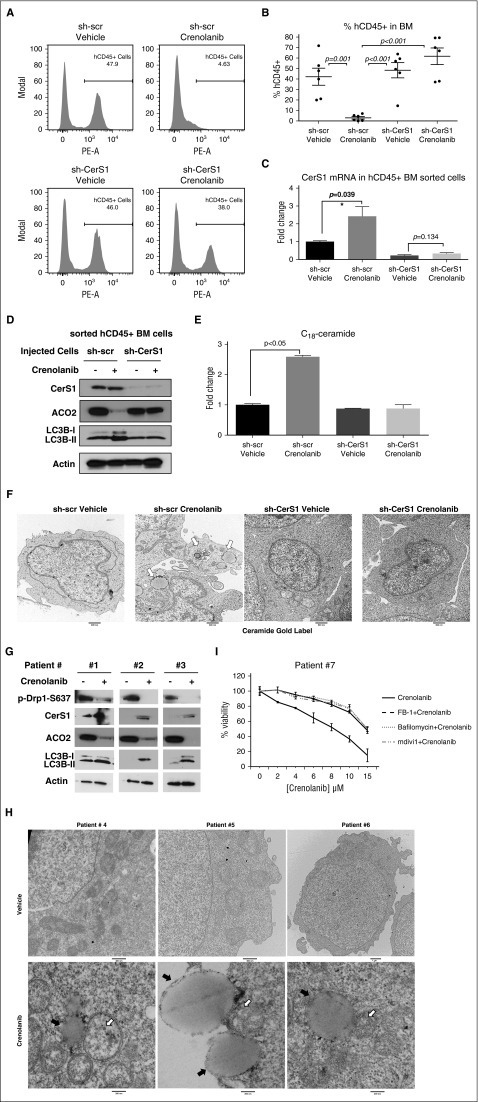

CerS1/C18-ceramide induces lethal mitophagy in response to FLT3 _targeting in mice and human AML blasts

To test whether CerS1 activation is required for FLT3-_targeted therapy in vivo, we injected MV4-11-sh-Scr or MV4-11-sh-CerS1 cells via tail vein in NSG mice. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with vehicle or 15 mg/kg crenolanib for 3 weeks (supplemental Figure 7A). Crenolanib-treated mice harboring sh-scr AML xenografts, but not sh-CerS1 xenografts, showed a reduction in liver and spleen weights, and elimination of CD45+ human AML cells from the mouse bone marrow indicative of reduced tumor burden (Figure 6A-B; supplemental Figure 7B-E). These data suggest that CerS1/C18-ceramide activation plays a key role in reducing AML burden in response to FLT3-ITD inhibition.

Figure 6.

CerS1-C18-ceramide–mediated lethal mitophagy is required for FLT3-_targeted therapy in the AML mouse model and human AML blasts. (A-B) FACS analysis to measure the percentage of injected AML cells (hCD45+ cells) in the bone marrow. Values indicate mean ± SD of n = 6 mice. P values were generated using ANOVA. (C) qPCR to measure CerS1 mRNA in sorted hCD45+ cells. (D) Western blot to measure CerS1, ACO2, and LC3B in sorted hCD45+ cells. (E) HPLC-MS-MS measuring C18-ceramide in sorted hCD45+ cells. Values indicate mean ± SD of n = 3 mice. P values were generated using the Student t test. (F) EM visualization of sorted hCD45+ cells from bone marrow of NSG mice with AML xenografts. (G) CD34+ bone marrow blasts obtained from FLT3-ITD+ patients were treated with 5 μM crenolanib for 24 hours, followed by western blot to detect p-Drp1 S637, CerS1, ACO2, and LC3B. (H) EM visualization of crenolanib-treated FLT3+ AML patient blasts labeled with ceramide antibody. White arrows indicate ceramide gold label in mitochondria and black arrows indicate autophagosomes. (I) Percentage of viability of AML patient blasts pretreated with either FB-1, bafilomycin, or mdivi1, followed by 5 μM crenolanib treatment of 24 hours. *P value of <.05 using the 2-sided Student t test.

To study the induction of mitophagy in vivo by CerS1/C18-ceramide in response to FLT3 inhibition, we injected NSG mice harboring sh-scr or sh-CerS1 xenografts with vehicle or 15 mg/kg crenolanib for only 5 days to obtain a sufficient number of hCD45+ AML cells for biochemical analyses (supplemental Figure 7B). hCD45+ AML cells sorted from crenolanib-treated mice harboring sh-Scr xenografts showed increased CerS1/ceramide generation and mitophagy induction, which were abrogated in hCD45+ AML cells sorted from crenolanib-treated mice harboring sh-CerS1 xenografts (Figure 6C-F). These data suggest that _targeting FLT3-ITD by crenolanib induces CerS1/C18-ceramide–mediated mitophagy in vivo.

Importantly, bone marrow blasts obtained from FLT3-ITD+ AML patients exhibited increased CerS1 and mitophagy (induction of LC3B lipidation, ACO2 degradation, and mitophagosome formation), consistent with decreased p-Drp1-S637, in response to crenolanib (Figure 6G-H). Moreover, pretreatment with FB-1 (CerS inhibitor), mdivi-1 (Drp1 inhibitor), or bafilomycin (autophagy inhibitor) protected AML patient blasts from crenolanib-induced cell death (Figure 6I). Thus, these data suggest that _targeting FLT3-ITD induces CerS1/C18-ceramide–mediated mitophagy in human AML blasts.

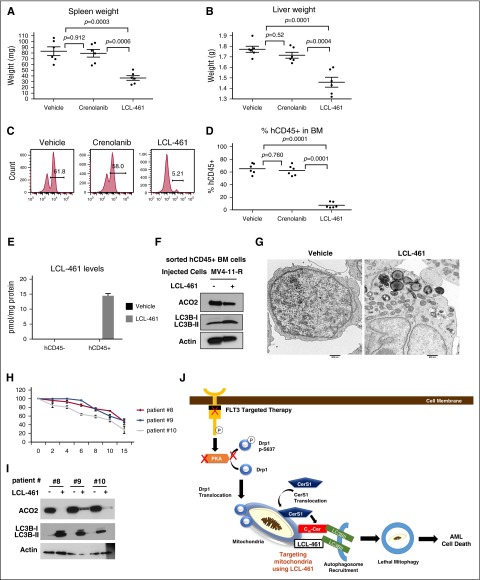

LCL-461 induces lethal mitophagy in drug-resistant AML xenografts in vivo

To investigate the therapeutic efficacy of LCL-461 for AML therapy in vivo, NSG mice harboring MV4-11-R xenografts were treated with vehicle, crenolanib (15 mg/kg), or LCL-461 (15 mg/kg) for 3 weeks. Crenolanib treatment was not effective in reducing tumor burden; however, LCL-461 treatment effectively reduced liver and spleen weights, and eliminated CD45+ human AML cells from the mouse bone marrow compared with vehicle-treated controls (Figure 7A-E; supplemental Figure 7F). Mechanistically, data showed that LCL-461 treatment induced mitophagy in hCD45+ AML cells sorted from mice harboring MV4-11-R xenografts, as detected by increased ACO2 degradation, increased LC3B lipidation, and formation of mitophagosomes by TEM (Figure 7F-G). Remarkably, LCL-461 levels were detected in CD45+ AML blasts but not in nonleukemic CD45− bone marrow cells in these mice (Figure 7E). Furthermore, we found that LCL-461 treatment induced lethal mitophagy in bone marrow blasts obtained from FLT3-ITD+ AML patients, as indicated by increased cell death, LC3B lipidation, and ACO2 degradation (Figure 7H-I).

Figure 7.

LCL-461 has anti-AML effect in AML mouse model and in human AML blasts. (A) Measured weights of harvested spleen at day 30 after injection of cells. (B) Measured weights of harvested liver. (C-D) FACS analysis to measure the percentage of injected MV4-11-R cells (hCD45+ cells) in the bone marrow. Values indicate mean ± SD of n = 6 mice. P values are generated using ANOVA. (E) MS measuring LCL-461 in sorted hCD45+ cells vs hCD45− cells. (F) Western blot to measure ACO2 and LC3B in sorted hCD45+ cells. (G) Electron microscopy visualization of the morphology of sorted hCD45+ cells obtained from bone marrow of mice injected with vehicle or LCL-461. Values indicate mean ± SD of n = 3 mice. P values are generated using the 2-sided Student t test. (H) AML bone marrow blasts obtained from FLT3+ patients were treated with different doses of LCL-461 to measure percentage of viability at 24 hours. (I) AML bone marrow blasts obtained from FLT3+ patients were treated with 8 μM LCL-461 followed by western blot to measure ACO2 matrix protein degradation and LC3B lipidation. (J) Scheme illustrating the mechanism by which _targeting mitochondria using LCL-461 results in lethal mitophagy in FLT3+ AML.

Furthermore, we obtained AML blasts from patients that are clinically sensitive or resistant to FLT3-_targeted therapy. LCL-461 induced mitophagy events in vitro and antileukemic effects in vivo in AML blasts obtained from clinically sensitive or clinically resistant patients (supplemental Figures 7G and 8A-D). Thus, these data suggest that _targeting mitochondria using LCL-461 to induce mitophagy is a novel alternative therapeutic strategy for drug-resistant FLT3-ITD+ AML in vivo and in blasts obtained from FLT3-ITD+ AML patients.

Discussion

FLT3-ITD–activating mutations present a major obstacle in the treatment of AML, and clinical trials using FLT3 inhibitors showed limited success.11,39 Therefore, it is important to define the mechanisms by which activation of FLT3 signaling modulates cell death, and to use these mechanistic data for the development of alternative strategies. The role of biologically active lipids, such as ceramide, in the response of AML to FLT3-ITD–_targeted therapy has not been described previously. Our data suggest that FLT-ITD signaling in AML cells reduces pro-cell death C18-ceramide synthesis by suppression of CerS1. Molecular or pharmacological _targeting of FLT3-ITD signaling induced CerS1/C18-ceramide generation, mediating mitophagy-dependent cell death in AML cell lines, AML xenografts in vivo, and AML blasts obtained from FLT3-ITD+ patients. Mechanistically, FLT3-ITD _targeting resulted in Drp1 activation via decreased p-Drp1-S637 by PKA inhibition, leading to mitochondrial translocation of CerS1 and increased mitochondrial C18-ceramide generation. Mitochondrial C18-ceramide interacted with LC3B-II to recruit autophagosomes to mitochondria for degradation via the ceramide-binding domain, including I35/F52 residues. Importantly, we show here that activation of mitophagy can be achieved by _targeting mitochondria using a highly soluble C18-ceramide analog drug LCL-461, which selectively accumulated in AML mitochondria to induce lethal mitophagy in AML cells resistant to crenolanib in situ and in vivo. LCL-461 also induced lethal mitophagy AML cells expressing various clinically relevant FLT3 mutations, and in AML blasts obtained from FLT3-ITD+ patients (Figure 7J).

Our data are consistent with previous studies demonstrating that other anti-AML drugs also mediate cell death by inducing autophagy.40-42 It has been suggested previously that loss of various autophagy genes or a decrease in autophagy flux can promote AML oncogenesis.41,43,44 In addition, a recent study provided biochemical and biological evidence that PKA activation is one of the downstream effectors of FLT3-ITD–dependent oncogenesis. It was shown that inhibition of PKA using H-89 enhanced the efficacy of the FLT3-ITD inhibitor.35 In addition, the possible crosstalk between FLT3-ITD signaling and Drp1 regulation was indicated in a previous study, which showed that suppressor of cytokine signaling 6 (SOCS6) inhibited FLT3 signaling through direct binding to p-FLT3 at Y591 and Y919, and promoted Drp1 translocation to mitochondria to induce mitochondrial fission.45,46 However, the involvement of mitochondrial degradation by ceramide-dependent mitophagy in response to FLT3-ITD _targeting to induce AML cell death has not been described previously.

Interestingly, when we analyzed CerS1 mRNA and its impact on survival in the TCGA AML database (Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network 2013), we found that out of 166 AML patients, 10 exhibited amplified CerS1 (>1.5-fold), who showed significantly longer overall and disease-free survival compared with patients with basal CerS1 mRNA abundance (P = .0118; supplemental Figure 8E). These data indicate that CerS1/C18-ceramide amplification/activation might be beneficial for AML patient survival and are thus consistent with our data. The Kaplan-Meier curves were generated using cBioPortal web-based software (http://www.cbioportal.org). However, FLT3-ITD status of the AML patient cohort is unknown, and thus clinical significance of CerS1/ceramide axis in the overall survival of AML patients with regard to FLT3-ITD activation needs to be further examined in a larger cohort.

Our studies also suggest that LCL-461 has an antileukemic effect in AML cells with activating FLT3 mutations in culture, in NSG mice harboring crenolanib-resistant AML xenografts, and in human FLT3-ITD+ AML blasts in situ. Modifying ceramide by adding a pyridinium ring in the sphingoid backbone allows the cationic ceramide to accumulate selectively in negatively charged mitochondria.31,37,47-50 Accumulation of LCL-461 was detected in mitochondria of FLT3-ITD+ AML blasts and not in that of normal bone marrow cells, possibly due to increased negatively charged mitochondria in AML cells resulting from the Warburg effect.51 Importantly, LCL-461 was efficacious in attenuating crenolanib resistance by inducing lethal mitophagy in FLT3-ITD AML blasts in vitro and in vivo. This highlights the ability of LCL-461 to bypass oncogenic FLT3-ITD signaling and attenuate cell-death resistance to FLT3-ITD inhibitor crenolanib.

Overall, studies presented here describe a novel mechanism of cell death in FLT3-ITD+ AML in which mitochondria are selectively _targeted by CerS1/C18-ceramide or exogenous ceramide analog drug LCL-461 in response to FLT3-ITD inhibition. Moreover, these data might have broader clinical implications as _targeting mitochondria by ceramide-dependent mitophagy52 provides a novel anticancer treatment strategy as mitochondrial bioenergetics and function might be required for production of ATP and intermediates used for macromolecule biosynthesis to induce cancer growth/proliferation and/or drug resistance.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lipidomics Shared Resource for measuring ceramide components by high-performance liquid chromatography–MS/MS, Nancy Smythe for her help with electron microscopy, the Cell and Molecular Imaging Core Facility at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), and the Flow Cytometry Core Facility at Hollings Cancer Center. The authors also thank Dennis Watson, Hary Drabkin, Amanda LaRue, Elizabeth Yeh, and James Norris at MUSC for their valuable input and feedback. The authors thank Patrick Brown and Donald Small (Johns Hopkins University) for providing various AML cell lines.

This work was supported by research funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Cancer Institute (NCI) grants CA088932, CA173687, and P01-CA203628, and from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research grant DE016572 (B.O.). The authors are thankful for the support by the James F. Bomar Myeloid Malignancy Research Fund held at the Hollings Cancer Center. This research was also supported in part by the Lipidomics Shared Resource, Hollings Cancer Center, Medical University of South Carolina (NIH NCI P30 CA138313), and the Center of Biomedical Research Excellence in Lipidomics and Pathobiology (NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences P30 GM103339).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: M.D. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, prepared the figures, and helped write the manuscript; S.G., R.N., R.J.T., N.O., and K.D.B. performed experiments; Z.M.S. designed and synthesized ceramide analogues; P.R., M.A., and S.K. provided human AML patient samples and Ba/f3 AML cell lines and helped analyze preclinical and clinical data; and B.O. designed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The patent for LCL-461 is licensed to Sphingogene Inc. Z.M.S. and B.O. are founding and scientific board members of Sphingogene Inc. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for S.G. is Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics, Uskudar University, Istanbul, Turkey.

Correspondence: Besim Ogretmen, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Medical University of South Carolina, Jonathan Lucas St, Room 512A, Charleston, SC 29425; e-mail: ogretmen@musc.edu.

References

- 1.Kadia TM, Ravandi F, Cortes J, Kantarjian H. Toward individualized therapy in acute myeloid leukemia: a contemporary review. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(6):820–828. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stone RM, DeAngelo DJ, Klimek V, et al. Patients with acute myeloid leukemia and an activating mutation in FLT3 respond to a small-molecule FLT3 tyrosine kinase inhibitor, PKC412. Blood. 2005;105(1):54–60. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiyoi H, Ohno R, Ueda R, Saito H, Naoe T. Mechanism of constitutive activation of FLT3 with internal tandem duplication in the juxtamembrane domain. Oncogene. 2002;21(16):2555–2563. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mizuki M, Fenski R, Halfter H, et al. Flt3 mutations from patients with acute myeloid leukemia induce transformation of 32D cells mediated by the Ras and STAT5 pathways. Blood. 2000;96(12):3907–3914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choudhary C, Schwäble J, Brandts C, et al. AML-associated Flt3 kinase domain mutations show signal transduction differences compared with Flt3 ITD mutations. Blood. 2005;106(1):265–273. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moreno I, Martín G, Bolufer P, et al. Incidence and prognostic value of FLT3 internal tandem duplication and D835 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2003;88(1):19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamamoto Y, Kiyoi H, Nakano Y, et al. Activating mutation of D835 within the activation loop of FLT3 in human hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2001;97(8):2434–2439. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.8.2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang W, Konopleva M, Shi YX, et al. Mutant FLT3: a direct _target of sorafenib in acute myelogenous leukemia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(3):184–198. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galanis A, Ma H, Rajkhowa T, et al. Crenolanib is a potent inhibitor of FLT3 with activity against resistance-conferring point mutants. Blood. 2014;123(1):94–100. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-10-529313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kampa-Schittenhelm KM, Heinrich MC, Akmut F, Döhner H, Döhner K, Schittenhelm MM. Quizartinib (AC220) is a potent second generation class III tyrosine kinase inhibitor that displays a distinct inhibition profile against mutant-FLT3, -PDGFRA and -KIT isoforms. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:19. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stein EM, Tallman MS. Emerging therapeutic drugs for AML. Blood. 2016;127(1):71–78. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-07-604538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomes LC, Scorrano L. Mitochondrial morphology in mitophagy and macroautophagy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833(1):205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dany M, Ogretmen B. Ceramide induced mitophagy and tumor suppression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1853(10 Pt B):2834–2845. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lemasters JJ. Variants of mitochondrial autophagy: types 1 and 2 mitophagy and micromitophagy (type 3). Redox Biol. 2014;2:749–754. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buhlman L, Damiano M, Bertolin G, et al. Functional interplay between Parkin and Drp1 in mitochondrial fission and clearance. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1843(9):2012–2026. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang CR, Blackstone C. Dynamic regulation of mitochondrial fission through modification of the dynamin-related protein Drp1. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1201:34–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frank S, Gaume B, Bergmann-Leitner ES, et al. The role of dynamin-related protein 1, a mediator of mitochondrial fission, in apoptosis. Dev Cell. 2001;1(4):515–525. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cereghetti GM, Stangherlin A, Martins de Brito O, et al. Dephosphorylation by calcineurin regulates translocation of Drp1 to mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(41):15803–15808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808249105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogretmen B, Hannun YA. Biologically active sphingolipids in cancer pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(8):604–616. doi: 10.1038/nrc1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saddoughi SA, Ogretmen B. Diverse functions of ceramide in cancer cell death and proliferation. Adv Cancer Res. 2013;117:37–58. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394274-6.00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Senkal CE, Ponnusamy S, Manevich Y, et al. Alteration of ceramide synthase 6/C16-ceramide induces activating transcription factor 6-mediated endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and apoptosis via perturbation of cellular Ca2+ and ER/Golgi membrane network. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(49):42446–42458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.287383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Principles of bioactive lipid signalling: lessons from sphingolipids. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(2):139–150. doi: 10.1038/nrm2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saddoughi SA, Garrett-Mayer E, Chaudhary U, et al. Results of a phase II trial of gemcitabine plus doxorubicin in patients with recurrent head and neck cancers: serum C₁₈-ceramide as a novel biomarker for monitoring response. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(18):6097–6105. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baran Y, Salas A, Senkal CE, et al. Alterations of ceramide/sphingosine 1-phosphate rheostat involved in the regulation of resistance to imatinib-induced apoptosis in K562 human chronic myeloid leukemia cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(15):10922–10934. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610157200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyers-Needham M, Ponnusamy S, Gencer S, et al. Concerted functions of HDAC1 and microRNA-574-5p repress alternatively spliced ceramide synthase 1 expression in human cancer cells. EMBO Mol Med. 2012;4(2):78–92. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201100189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang W, Ogretmen B. Autophagy paradox and ceramide. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1841(5):783–792. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Young MM, Kester M, Wang HG. Sphingolipids: regulators of crosstalk between apoptosis and autophagy. J Lipid Res. 2013;54(1):5–19. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R031278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russo SB, Baicu CF, Van Laer A, et al. Ceramide synthase 5 mediates lipid-induced autophagy and hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(11):3919–3930. doi: 10.1172/JCI63888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sentelle RD, Senkal CE, Jiang W, et al. Ceramide _targets autophagosomes to mitochondria and induces lethal mitophagy. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8(10):831–838. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto T, Hasegawa H, Hakogi T, Katsumura S. Versatile synthetic method for sphingolipids and functionalized sphingosine derivatives via olefin cross metathesis. Org Lett. 2006;8(24):5569–5572. doi: 10.1021/ol062258l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szulc ZM, Bielawski J, Gracz H, et al. Tailoring structure-function and _targeting properties of ceramides by site-specific cationization. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14(21):7083–7104. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bielawski J, Pierce JS, Snider J, Rembiesa B, Szulc ZM, Bielawska A. Sphingolipid analysis by high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS). Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;688:46–59. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6741-1_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ding WX, Ni HM, Li M, et al. Nix is critical to two distinct phases of mitophagy, reactive oxygen species-mediated autophagy induction and Parkin-ubiquitin-p62-mediated mitochondrial priming. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(36):27879–27890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.119537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fric J, Lim CX, Mertes A, et al. Calcium and calcineurin-NFAT signaling regulate granulocyte-monocyte progenitor cell cycle via Flt3-L. Stem Cells. 2014;32(12):3232–3244. doi: 10.1002/stem.1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang X, Liu L, Sternberg D, et al. The FLT3 internal tandem duplication mutation prevents apoptosis in interleukin-3-deprived BaF3 cells due to protein kinase A and ribosomal S6 kinase 1-mediated BAD phosphorylation at serine 112. Cancer Res. 2005;65(16):7338–7347. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beckham TH, Lu P, Jones EE, et al. LCL124, a cationic analog of ceramide, selectively induces pancreatic cancer cell death by accumulating in mitochondria. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;344(1):167–178. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.199216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dahm F, Bielawska A, Nocito A, et al. Mitochondrially _targeted ceramide LCL-30 inhibits colorectal cancer in mice. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(1):98–105. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Syed I, Szulc ZM, Ogretmen B, Kowluru A. L- threo -C6-pyridinium-ceramide bromide, a novel cationic ceramide, induces NADPH oxidase activation, mitochondrial dysfunction and loss in cell viability in INS 832/13 β-cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2012;30(4):1051–1058. doi: 10.1159/000341481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kadia TM, Ravandi F, Cortes J, Kantarjian H. New drugs in acute myeloid leukemia. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(5):770–778. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fang J, Rhyasen G, Bolanos L, et al. Cytotoxic effects of bortezomib in myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia depend on autophagy-mediated lysosomal degradation of TRAF6 and repression of PSMA1. Blood. 2012;120(4):858–867. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-407999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watson AS, Mortensen M, Simon AK. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia. Cell Cycle. 2011;10(11):1719–1725. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.11.15673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wei Y, Kadia T, Tong W, et al. The combination of a histone deacetylase inhibitor with the BH3-mimetic GX15-070 has synergistic antileukemia activity by activating both apoptosis and autophagy. Autophagy. 2010;6(7):976–978. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.7.13117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lalaoui N, Johnstone R, Ekert PG. Autophagy and AML--food for thought. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23(1):5–6. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mortensen M, Watson AS, Simon AK. Lack of autophagy in the hematopoietic system leads to loss of hematopoietic stem cell function and dysregulated myeloid proliferation. Autophagy. 2011;7(9):1069–1070. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.9.15886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kazi JU, Sun J, Phung B, Zadjali F, Flores-Morales A, Rönnstrand L. Suppressor of cytokine signaling 6 (SOCS6) negatively regulates Flt3 signal transduction through direct binding to phosphorylated tyrosines 591 and 919 of Flt3. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(43):36509–36517. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.376111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kabir NN, Sun J, Rönnstrand L, Kazi JU. SOCS6 is a selective suppressor of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(11):10581–10589. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2542-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Novgorodov SA, Szulc ZM, Luberto C, et al. Positively charged ceramide is a potent inducer of mitochondrial permeabilization. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(16):16096–16105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411707200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rossi MJ, Sundararaj K, Koybasi S, et al. Inhibition of growth and telomerase activity by novel cationic ceramide analogs with high solubility in human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;132(1):55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dindo D, Dahm F, Szulc Z, et al. Cationic long-chain ceramide LCL-30 induces cell death by mitochondrial _targeting in SW403 cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5(6):1520–1529. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Senkal CE, Ponnusamy S, Rossi MJ, et al. Potent antitumor activity of a novel cationic pyridinium-ceramide alone or in combination with gemcitabine against human head and neck squamous cell carcinomas in vitro and in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317(3):1188–1199. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.101949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Modica-Napolitano JS, Aprille JR. Delocalized lipophilic cations selectively _target the mitochondria of carcinoma cells. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;49(1-2):63–70. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weinberg SE, Chandel NS. _targeting mitochondria metabolism for cancer therapy. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11(1):9–15. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]