Abstract

Background

Lay health workers (LHWs) perform functions related to healthcare delivery, receive some level of training, but have no formal professional or paraprofessional certificate or tertiary education degree. They provide care for a range of issues, including maternal and child health. For LHW programmes to be effective, we need a better understanding of the factors that influence their success and sustainability. This review addresses these issues through a synthesis of qualitative evidence and was carried out alongside the Cochrane review of the effectiveness of LHWs for maternal and child health.

Objectives

The overall aim of the review is to explore factors affecting the implementation of LHW programmes for maternal and child health.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, OvidSP (searched 21 December 2011); MEDLINE Ovid In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, OvidSP (searched 21 December 2011); CINAHL, EBSCO (searched 21 December 2011); British Nursing Index and Archive, OvidSP (searched 13 May 2011). We searched reference lists of included studies, contacted experts in the field, and included studies that were carried out alongside the trials from the LHW effectiveness review.

Selection criteria

Studies that used qualitative methods for data collection and analysis and that focused on the experiences and attitudes of stakeholders regarding LHW programmes for maternal or child health in a primary or community healthcare setting.

Data collection and analysis

We identified barriers and facilitators to LHW programme implementation using the framework thematic synthesis approach. Two review authors independently assessed study quality using a standard tool. We assessed the certainty of the review findings using the CerQual approach, an approach that we developed alongside this and related qualitative syntheses. We integrated our findings with the outcome measures included in the review of LHW programme effectiveness in a logic model. Finally, we identified hypotheses for subgroup analyses in future updates of the review of effectiveness.

Main results

We included 53 studies primarily describing the experiences of LHWs, programme recipients, and other health workers. LHWs in high income countries mainly offered promotion, counselling and support. In low and middle income countries, LHWs offered similar services but sometimes also distributed supplements, contraceptives and other products, and diagnosed and treated children with common childhood diseases. Some LHWs were trained to manage uncomplicated labour and to refer women with pregnancy or labour complications.

Many of the findings were based on studies from multiple settings, but with some methodological limitations. These findings were assessed as being of moderate certainty. Some findings were based on one or two studies and had some methodological limitations. These were assessed have low certainty.

Barriers and facilitators were mainly tied to programme acceptability, appropriateness and credibility; and health system constraints. Programme recipients were generally positive to the programmes, appreciating the LHWs’ skills and the similarities they saw between themselves and the LHWs. However, some recipients were concerned about confidentiality when receiving home visits. Others saw LHW services as not relevant or not sufficient, particularly when LHWs only offered promotional services. LHWs and recipients emphasised the importance of trust, respect, kindness and empathy. However, LHWs sometimes found it difficult to manage emotional relationships and boundaries with recipients. Some LHWs feared blame if care was not successful. Others felt demotivated when their services were not appreciated. Support from health systems and community leaders could give LHWs credibility, at least if the health systems and community leaders had authority and respect. Active support from family members was also important.

Health professionals often appreciated the LHWs’ contributions in reducing their workload and for their communication skills and commitment. However, some health professionals thought that LHWs added to their workload and feared a loss of authority.

LHWs were motivated by factors including altruism, social recognition, knowledge gain and career development. Some unsalaried LHWs wanted regular payment, while others were concerned that payment might threaten their social status or lead recipients to question their motives. Some salaried LHWs were dissatisfied with their pay levels. Others were frustrated when payment differed across regions or institutions. Some LHWs stated that they had few opportunities to voice complaints.

LHWs described insufficient, poor quality, irrelevant and inflexible training programmes, calling for more training in counselling and communication and in topics outside their current role, including common health problems and domestic problems. LHWs and supervisors complained about supervisors’ lack of skills, time and transportation. Some LHWs appreciated the opportunity to share experiences with fellow LHWs.

In some studies, LHWs were traditional birth attendants who had received additional training. Some health professionals were concerned that these LHWs were over‐confident about their ability to manage danger signs. LHWs and recipients pointed to other problems, including women’s reluctance to be referred after bad experiences with health professionals, fear of caesarean sections, lack of transport, and cost. Some LHWs were reluctant to refer women on because of poor co‐operation with health professionals.

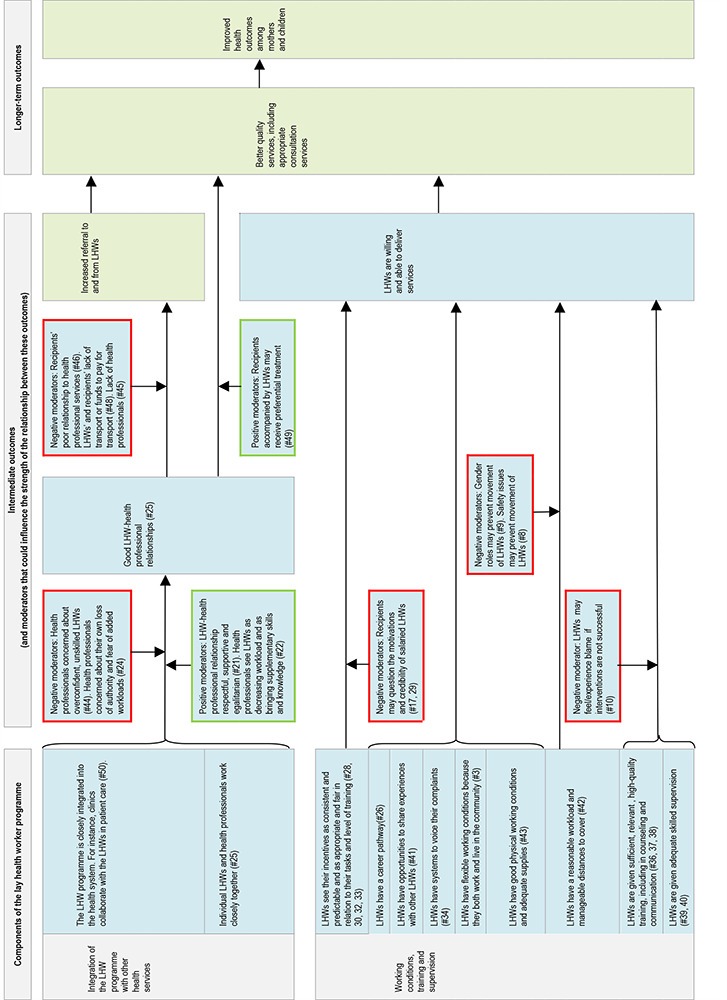

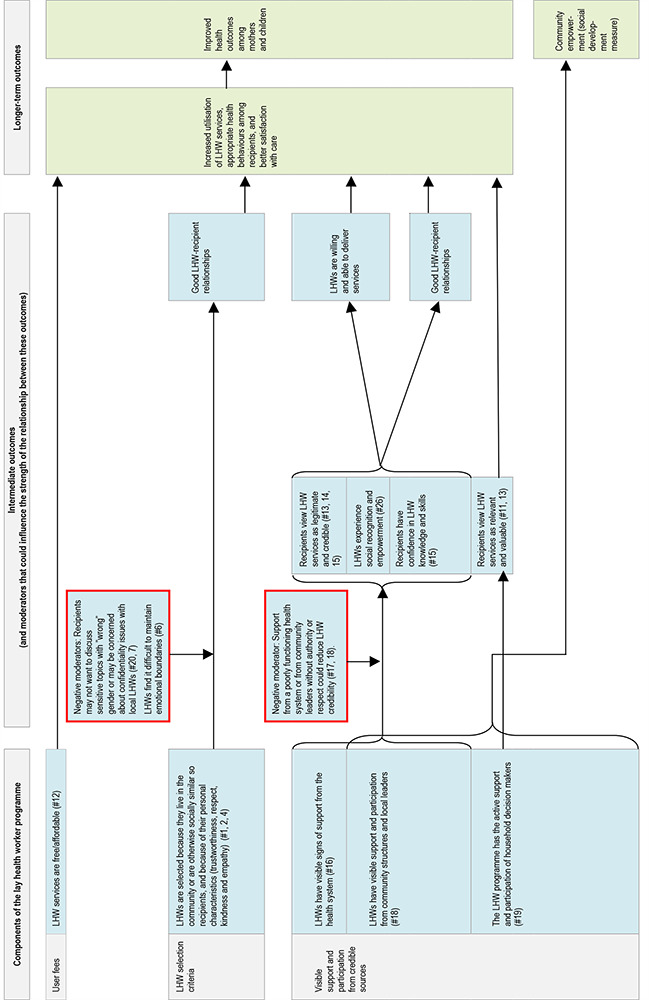

We organised these findings and the outcome measures included in the review of LHW programme effectiveness in a logic model. Here we proposed six chains of events where specific programme components lead to specific intermediate or long‐term outcomes, and where specific moderators positively or negatively affect this process. We suggest how future updates of the LHW effectiveness review could explore whether the presence of these components influences programme success.

Authors' conclusions

Rather than being seen as a lesser trained health worker, LHWs may represent a different and sometimes preferred type of health worker. The close relationship between LHWs and recipients is a programme strength. However, programme planners must consider how to achieve the benefits of closeness while minimizing the potential drawbacks. Other important facilitators may include the development of services that recipients perceive as relevant; regular and visible support from the health system and the community; and appropriate training, supervision and incentives.

Plain language summary

Factors that can influence the success of lay health worker programmes for maternal and child health

This review was carried out by researchers in The Cochrane Collaboration. It summarises the findings of 53 studies that explore factors influencing the success of lay health worker (LHW) programmes for mothers and child health. This review was carried out alongside the Cochrane review assessing the effectiveness of LHW programmes on maternal and child health.

What is a lay health worker?

A LHW is a lay person who has received some training to deliver healthcare services but is not a health professional. In most of the studies in this review, LHWs offered health care to people who were on low incomes living in wealthy countries or to people living in poor countries. The LHWs in wealthy countries offered health promotion, counselling and support. The LHWs in poor countries offered similar services but they sometimes also distributed food supplements, contraceptives and other products, treated children with common childhood diseases, or managed women in uncomplicated labour.

What the research says

The studies described the experiences of LHWs, mothers, programme managers, and other health workers with LHW programmes. Many of our findings were based on studies from different settings and had some methodological problems. We judged these findings to have moderate certainty. Some findings were only based on one or two studies that had some methodological problems and were judged to be of low certainty.

Mothers were generally positive about the programmes. They appreciated the LHWs’ skills and the similarities they saw between themselves and the LHWs. However, some mothers were concerned about confidentiality when receiving home visits. Others saw LHW services as not relevant or not sufficient, particularly when LHWs only offered promotional services. LHWs and mothers emphasised the importance of trust, respect, kindness and empathy. However, LHWs sometimes found it difficult to manage emotional relationships and boundaries with mothers. Some LHWs feared blame if health care was not successful. Others felt demotivated when their services were not appreciated. Support from health systems and community leaders could give LHWs credibility if these health systems and community leaders had authority and respect. Active support from family members was also important.

Health professionals often appreciated the LHWs' contributions to reducing their workload, and their communication skills and commitment. However, some health professionals thought that LHWs added to their own workloads and feared a loss of authority.

LHWs were motivated by altruism, social recognition, knowledge gain and career development. Some unsalaried LHWs wanted regular payment. Others were concerned that payment might threaten their social status or lead people to question their motives. Some salaried LHWs were dissatisfied with their pay levels. Others were frustrated when other LHWs had higher salaries. Some LHWs said that they had few opportunities to voice complaints.

Some LHWs described insufficient, poor quality and irrelevant training programmes. They called for more training in counselling and communication and in topics outside their current role, including common health problems and domestic problems. LHWs and supervisors complained about supervisors’ lack of skills, time and transportation. Some LHWs appreciated the opportunity to share experiences with other LHWs.

Some LHWs were traditional birth attendants who had received additional training. Some health professionals were concerned that these LHWs were over‐confident about their ability to manage danger signs. LHWs and mothers identified women’s reluctance to be referred after bad experiences with health professionals, fear of caesarean sections, lack of transport, and costs. Some LHWs were also reluctant to refer women on because of poor co‐operation with health professionals.

We organized these findings into chains of events where we have proposed how certain LHW programme elements might lead to greater programme success.

Authors’ conclusions

Rather than being seen as a lesser trained health worker, LHWs represent a different and sometimes preferred type of health worker. The often close relationship between LHWs and their recipients is a strength of such programmes. However, programme planners must consider how to achieve the benefits of closeness while avoiding the problems. It may also be important to offer services that recipients perceive as relevant; to ensure regular and visible support from other health workers and community leaders; and to offer appropriate training, supervision and incentives.

Background

The Millennium Development Goals 4, 5 and 6 aim to reduce child mortality, improve maternal health, and combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases. A key obstacle to the achievement of these goals is the chronic shortage and poor distribution of health workers in many countries (WHO 2010). One important approach to this problem is the moving of tasks to health workers with less training, or 'task‐shifting' (sometimes referred to as 'optimising') for instance by transferring certain tasks from doctors to nurses, midwives, or lay health workers. By re‐organising the health workforce in this way, policy makers hope to make more efficient use of the human resources already available and thereby expand and strengthen coverage of key health interventions (WHO 2012; WHO/PEPFAR/UNAIDS 2007).

Description of the intervention

Lay health workers (LHWs) perform diverse functions related to healthcare delivery. While LHWs are usually provided with job‐related training they have no formal professional or paraprofessional tertiary education, and can be involved in either paid or voluntary care (Lewin 2005). The term 'lay health worker' is thus broad in scope and includes, for example, community health workers, village health workers, treatment supporters and birth attendants.

The primary healthcare approach adopted by the World Health Organization (WHO) at Alma‐Ata promoted the initiation and rapid expansion of LHW programmes in low and middle income country settings, including a number of large national programmes, in the 1970s (Walt 1990). However, the effectiveness and costs of such programmes came to be questioned in the following decade, particularly at national level. Several evaluations were conducted and these indicated difficulties in the scaling up of LHW programmes as a consequence of a range of factors. Important constraints included inadequate training and ongoing supervision; insecure funding for incentives, equipment and drugs; failure to integrate LHW initiatives with the formal health system; poor planning; and opposition from health professionals (Frankel 1992; Walt 1990). These constraints led to poor quality care and difficulties in retaining trained LHWs in many of the programmes.

The 1990s saw renewed interest in community or LHW programmes in low and middle income countries. This was prompted by a number of factors including the growing AIDS epidemic; the resurgence of other infectious diseases; and the failure of the formal health system to provide adequate care for people with chronic illnesses (Hadley 2000; Maher 1999). The growing emphasis on decentralisation and partnership with community‐based organisations also contributed to this renewed interest. In high income country settings, a perceived need for mechanisms to deliver health care to minority communities and to support people with a wide range of health issues (Hesselink 2009; Witmer 1995) led to further growth in a variety of LHW interventions.

More recently, the growing focus on the human resource crisis in health care in many low and middle income countries has re‐energised debates regarding the roles that LHWs may play in extending services to 'hard to reach' groups and areas, and in substituting for health professionals for a range of tasks (Chopra 2008; WHO 2005; WHO 2006; WHO 2007). Task shifting is not a new concept. However, it has been given particular prominence and urgency in the face of the demands placed on health systems, in a number of settings, by the increased need for treatment of HIV/AIDS (Hermann 2009; Lehmann 2009; Schneider 2008; Zachariah 2009). Within this context, it is thought that LHWs may be able to play an important role in helping to achieve the Millennium Development Goals for health, particularly for child survival and treatment of tuberculosis (TB) and HIV/AIDS (Chen 2004; Filippi 2006; Haines 2007; Lewin 2008). For example, LHWs may be one route to expanding the coverage of effective neonatal and child health interventions, such as exclusive breastfeeding and community‐based case management of pneumonia, which remain under 50% in many low and middle income countries (Darmstadt 2005).

In contrast to earlier initiatives that tended to focus on generalist LHWs delivering a range of services within communities, more recent programmes have often been vertical in their approaches. In these programmes LHWs deliver a single or a small number of focused interventions addressing a particular health issue, such as promotion of vaccination; or one aspect of treatment care, such as supporting treatment adherence for people with tuberculosis (TB) (Lehmann 2007; Schneider 2008).

Why it is important to do this review

The Cochrane review on the effectiveness of LHW programmes for maternal and child health and infectious diseases (Lewin 2010) identified a total of 82 randomised trials, representing a substantial body of evidence regarding the effectiveness of these types of programmes. In these trials, LHWs received a small amount of training to perform a range of health services, often _targeting common causes of childhood mortality and morbidity. The review concluded that these types of programmes can effectively deliver key maternal and child health interventions in primary and community health care, including interventions to increase childhood immunisation rates and breastfeeding rates.

While the review concluded that this approach is promising, the results of these trials were heterogeneous, which, given the complexity of these types of interventions, was not unexpected. In addition, the level of organisation and support used for these interventions may have been higher than in real‐life settings. If these types of interventions are to be successfully implemented and scaled up, we need a greater understanding of the factors that may influence their success and sustainability. These include the values, preferences, knowledge and skills of stakeholders, and the feasibility and applicability of the intervention for particular settings and healthcare systems (see Table 1 for an overview of factors affecting implementation). While Cochrane reviews of effectiveness are not designed to answer these types of questions, there is growing acknowledgement that syntheses of qualitative research can address questions such as these.

1. Key domains of the SURE framework.

| Level | Factors affecting implementation |

| Recipients of care | Knowledge and skills |

| Attitudes regarding programme acceptability, appropriateness and credibility | |

| Motivation to change or adopt new behavior | |

| Providers of care | Knowledge and skills |

| Attitudes regarding programme acceptability, appropriateness and credibility | |

| Motivation to change or adopt new behavior | |

|

Other stakeholders (including other healthcare providers, community health committees, community leaders, programme managers, donors, policymakers and opinion leaders) |

Knowledge and skills |

| Attitudes regarding programme acceptability, appropriateness and credibility | |

| Motivation to change or adopt new behavior | |

| Health system constraints | Accessiblity of care |

| Financial resources | |

| Human resources | |

| Educational and training system, including recruitment and selection | |

| Clinical supervision, support structures and guidelines | |

| Internal communication | |

| External communication | |

| Allocation of authority | |

| Accountability | |

| Community participation | |

| Management and/or leadership | |

| Information systems | |

| Scale of private sector care | |

| Facilities | |

| Patient flow processes | |

| Procurement and distribution systems | |

| Incentives | |

| Bureaucracy | |

| Relationship with norms and standards | |

| Social and political constraints | Ideology |

| Governance | |

| Short‐term thinking | |

| Contracts | |

| Legislation or regulation | |

| Donor policies | |

| Influential people | |

| Corruption | |

| Political stability and commitment |

It is also increasingly recognised that bringing together qualitative studies in one synthesis can add value by allowing us to see both similarities and differences that exist across various contexts. As with systematic reviews of effectiveness, syntheses of qualitative data should be carried out in a systematic and transparent way. The last few years have seen strong development in the methodology for synthesising data from multiple qualitative studies, including within The Cochrane Collaboration (Noyes 2009), and the Cochrane Qualitative Research Methods Group has identified around 500 such syntheses.

While high quality syntheses of qualitative evidence can on their own prove valuable to researchers and policymakers, pairing qualitative syntheses with systematic reviews of (quantitative) effectiveness data allows for even more comprehensive insights into single topic areas. At least one Cochrane review has previously prompted a 'matching' synthesis of qualitative data. The Cochrane review of directly observed therapy (DOT) versus self‐administered treatment for adherence to TB treatment showed that DOT, despite its widespread use, does not achieve better outcomes (Volmink 2007). Two parallel reviews, both co‐authored by members of the current research team (Munro 2007; Noyes 2007), searched for qualitative studies on factors explaining non‐adherence to TB treatment. Together, these syntheses of qualitative research not only provided supporting evidence regarding the intervention’s lack of effect but also helped explain this lack of effect and informed policy and the design of more appropriate interventions (Garner 2007). Qualitative evidence also helped to clarify the many often context‐specific barriers and facilitators to accessing and complying with complex interventions to promote medicines management and treatment.

Pairing reviews of effectiveness with reviews of qualitative studies is equally relevant in the field of health workforce interventions, and a large body of relevant qualitative research exists. This research has described barriers and facilitators to the success of interventions _targeting different aspects of human resources for health. These barriers and facilitators include the attitudes and experience of the health workers themselves and also those of other stakeholders such as the health professionals they work with or whose tasks they have taken over, and the communities they serve. On the one hand, health workers taking on new tasks may appreciate the opportunity to be more useful as well as to gain increased salaries and public recognition (De Brouwere 2009). On the other hand, task shifting may not be accompanied by sufficient supervision or compensation and can create confusion, role conflicts and competition between health worker groups (De Brouwere 2009; Yakan 2009).

Previously we had attempted to identify all qualitative studies that were carried out alongside the 82 trials included in the review of LHW programme effectiveness. We did this by contacting authors of all the included trials, checking papers for references to qualitative research, searching PubMed for related studies, and carrying out citation searches. However, we were only able to find qualitative research that had been done during or after the trial for 14 (17%) of the trials (Glenton 2011). In addition, descriptions of qualitative methods and results were often sparse. Therefore, we decided to look for qualitative studies that explored LHW programmes either alongside or outside a trial context.

This review is one of a series of reviews that aimed to inform the World Health Organization's 'Recommendations for Optimizing Health Worker Roles to Improve Access to key Maternal and Newborn Health Interventions through Task Shifting' (OPTIMIZEMNH) (WHO 2012).

Objectives

The overall aim of the review is to explore factors affecting the implementation of lay health worker (LHW) programmes for maternal and child health.

The review has the following objectives:

to identify, appraise and synthesise qualitative research evidence on the barriers and facilitators to the implementation of LHW programmes for maternal and child health;

to integrate the findings of this review with the findings of the Cochrane review of effectiveness of LHW programmes (Lewin 2013) so as to enhance and extend our understanding of how these complex interventions work, and how context impacts on implementation;

to identify hypotheses for undertaking subgroup analyses in future updates of the Cochrane review of the effectiveness of LHW programmes (Lewin 2013).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included studies that used qualitative study designs such as ethnographic research, case studies, process evaluations and mixed methods designs. We included these studies if they had used qualitative methods for data collection (including focus group and individual interviews, observation, and document analysis) and qualitative methods for data analysis (including thematic analysis or any other appropriate qualitative analysis method that enabled analysis of text and observations and narrative presentation of findings). We therefore excluded studies that had collected data using qualitative methods but had analysed these data using quantitative methods.

Types of participants

We included studies that focused on the experiences and attitudes of stakeholders about lay health worker programmes in any country. Participants could include lay health workers, patients and their families, policy makers, programme managers, other health workers, or any others involved in or affected by the programmes.

Types of interventions

We included studies of programmes that were delivered in a primary or community healthcare setting; that intend to improve maternal or child health; and that had used any type of lay health worker, including community health workers, village health workers, birth attendants, peer counsellors, nutrition workers and home visitors.

For the purpose of this review, we defined a lay health worker as any health worker who:

performs functions related to healthcare delivery,

is trained in some way in the context of the intervention, but

has received no formal professional or paraprofessional certificate or tertiary education degree (Lewin 2005).

We defined maternal and child health care as follows:

child health: health care aimed at improving the health of children aged less than five years

maternal health: health care aimed at improving reproductive health, ensuring safe motherhood, or directed at women in their role as carers for children aged less than five years (Lewin 2010)

We included studies where services were delivered in a hospital setting if they also included a primary or community health care component.

While the Cochrane intervention review also evaluated the effectiveness of lay health worker programmes on infectious diseases, we decided not to include this topic in the current synthesis of qualitative evidence so as to make it more manageable.

Types of outcome measures

Phenomena of interest

We included studies where the primary focus was the experiences and attitudes of stakeholders towards lay health worker programmes.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases for eligible studies:

MEDLINE IN‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations December 20, 2011, OvidSP (searched 21.12.11)

MEDLINE, 1948 to November Week 3 2011, OvidSP (searched 21.12.11)

British Nursing Index and Archive, 1985 to May 2011, OvidSP (searched 13.05.11)

CINAHL, 1981 to present, EbscoHost (searched 21.12.11).

A search strategy had previously been developed for the Cochrane review of lay health worker programme effectiveness (Lewin 2010), including a comprehensive list of terms used in the literature to describe lay health worker interventions. We used these terms but removed the methods filter that was used to identify randomised trials. When searching MEDLINE (Appendix 1) and CINAHL (Appendix 2), we instead made use of their filter for qualitative studies, choosing the “specificity” alternative for MEDLINE and the “Qualitative – Best balance” alternative for CINAHL. When searching the British Nursing Index (Appendix 3), we used terms based on the MEDLINE methods filter.

We limited searches to English for feasibility reasons, given that it would be extremely time‐consuming and costly to undertake full text translation into English of qualitative papers for inclusion in this synthesis.

Other sources

In addition to the electronic searches, we contacted experts in the field, and searched reference lists of included studies. We also included studies that we had previously identified as having been carried out alongside the trials from the lay health worker programme effectiveness review (Glenton 2011).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed the titles and abstracts of the identified records to evaluate their eligibility. The full text of all the papers identified as potentially relevant by one or both review authors were retrieved. These papers were then assessed independently by two review authors. Disagreements between the review authors was resolved via discussion or, when required, by seeking a third review author's view. Where appropriate, we contacted the study authors for further information.

While systematic reviews of intervention effectiveness aim to include all relevant trials in order to avoid bias, this is not necessarily the case for syntheses of qualitative studies. In fact, too great a number of included studies can threaten the quality of data analysis, although there are few guidelines as to the ideal number of papers to include. In addition, the purpose of these syntheses is interpretive explanation rather than predictive (Doyle 2003), and "the results of a conceptual synthesis will not change if ten rather than five studies contain the same concept, but will depend on the range of concepts found in the studies, their context, and whether they are in agreement or not" (Thomas 2008). It may therefore be unnecessary to locate every available study and review authors may aim for a sample that is purposive rather than exhaustive (Doyle 2003).

Following from this standpoint, we utilised purposive sampling in order to arrive at a group of studies that provided geographical coverage. By achieving this coverage, we hoped to ensure a greater variation in contexts and thereby greater conceptual diversity. This aim of achieving geographical coverage was also driven by the fact that the review was developed to complement the review of lay health worker programme effectiveness, which included studies from several regions of the world. An additional reason was that the OPTIMIZEMNH guidance that our review aimed to inform was global, and geographical coverage was therefore regarded as helpful. However, we were concerned that our exclusion of studies in languages other than English would negatively affect this goal. After our initial round of study inclusion, we saw that studies from North America and UK were well‐represented while we had few studies from Latin America. We therefore decided that when we were in doubt about the inclusion of a particular study, we would be lenient towards studies from Latin America while we would be particularly stringent towards studies from North America and the UK. In most cases, this meant being particularly stringent about our requirement that studies should have as their primary focus the experiences and attitudes of stakeholders towards lay health worker programmes. The same requirement was applied particularly leniently for Latin American studies. In a few cases, we also applied the definition of “healthcare” stringently for studies from North America and the UK, excluding a few studies where lay health workers focused on child accident prevention and on social support, for instance support for parents of children with special needs. Finally, we excluded a small number of studies from the UK because they overlapped greatly with other studies in terms of the topics and settings covered (See Characteristics of excluded studies).

Data extraction and management

We developed a data extraction form that was informed by the SURE framework (The SURE Collaboration 2011) (See Table 1 for an overview of the key domains of the SURE framework). This framework focuses on barriers to implementing health systems changes and includes the following factors: (a) knowledge and skills; attitudes regarding programme acceptability, appropriateness and credibility; and motivation to change or adopt new behaviours among recipients of care, providers of care, and other stakeholders; (b) health system constraints (including accessibility of care, financial resources, human resources, educational system, clinical supervision, internal communication, external communication, allocation of authority, accountability, management or leadership (or both), information systems, facilities, patient flow processes, procurement and distribution systems, incentives, bureaucracy, and relationship with norms and standards); and (c) social and political constraints (including ideology, short‐term thinking, contracts, legislation or regulations, donor policies, influential people, corruption, and political stability). In syntheses of qualitative research, the "informants" are the authors of the individual studies rather than the participants in these studies. The authors' interpretations, presented for instance through themes and categories, therefore represent our data. While the authors' interpretations were primarily collected from the results sections of each paper, author interpretations were sometimes also found in the discussion sections, and these were also extracted when relevant and when well‐supported by data.

We also extracted information concerning the first author’s name; year of publication; language; country of study; clinical area; study setting (primary health centre or community; rural / urban, etc).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

As this is a synthesis of qualitative studies, we did not carry out any assessment of risk of bias for the included studies. Instead, we assessed the quality of the included studies as described below.

Assessment of the quality of the included qualitative studies

Our inclusion criteria specified that studies needed to use both qualitative data collection and analysis methods. This criterion also constituted a basic quality threshold. In addition, and following Cochrane Qualitative Research Methods Group guidance (Noyes 2011), two researchers independently applied a set of quality criteria to each included study. Disagreements were then resolved by seeking a third review author's view. Appraisal was performed using some of the main elements of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) quality assessment tool for qualitative studies (CASP 2006), as in other syntheses of qualitative evidence (Carlsen 2007; Munro 2007). See Table 2 for an overview of the quality criteria used.

2. Quality criteria assessment.

| Question | Yes/ somewhat | No | |

| 1. | Is this study qualitative research? | 53 | 0 |

| 2. | Is the study context clearly described? | 42 | 11 |

| 2. | Is there evidence of researcher reflexivity? | 15 | 38 |

| 4. | Is the sampling method clearly described and appropriate for the research question? | 45 | 8 |

| 5. | Is the method of data collection clearly described and appropriate to the research question? | 53 | 0 |

| 6. | Is the method of analysis clearly described and appropriate to the research question? | 41 | 12 |

| 7. | Are the claims made supported by sufficient evidence? I.e. did the data provide sufficient depth, detail and richness? | 46 | 7 |

We included studies that met our inclusion criteria regardless of study quality. We used the quality assessment when judging the relative contribution of each study to the development of explanations and relationships, as described in more detail below. It has been noted that poorer quality studies tend to contribute less to the synthesis (Atkins 2008). Therefore, the synthesis becomes ‘‘weighted’’ towards the findings of the better quality studies. Also, there is currently no consensus among qualitative researchers on the role of quality criteria and how they should be applied, and there is ongoing debate about how study quality should be assessed for the purposes of systematic reviews (Atkins 2008).

Appraisal of certainty of review findings

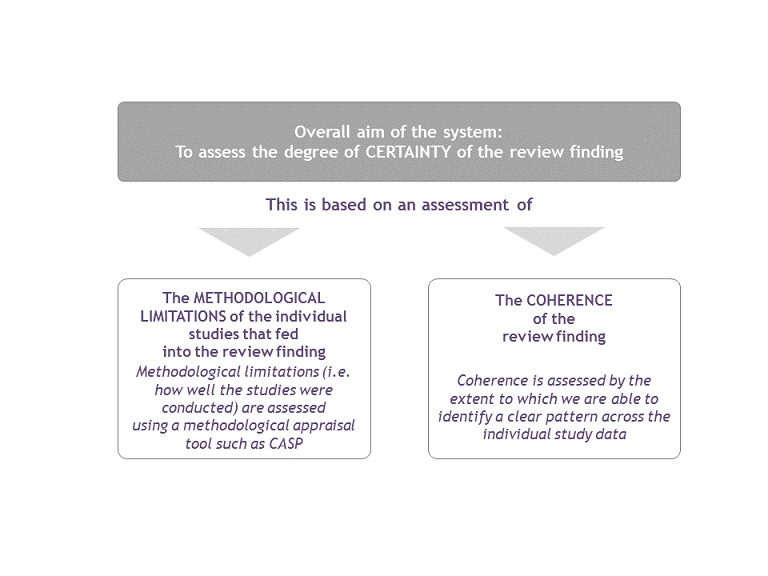

GRADE is now an accepted approach to assessing the certainty of findings from reviews of effectiveness (Guyatt 2011). However, few methods for assessing the certainty of findings drawn from syntheses of qualitative evidence have been developed. In connection with the development this synthesis and other syntheses of qualitative research (Colvin 2013; Rashidian 2013) carried out to inform the WHO OPTIMIZEMNH recommendations, we therefore chose to develop a system which we refer to as the CerQual (certainty of the qualitative evidence) approach (Figure 1).

1.

The CerQual approach

In the CerQual approach our assessment of certainty is based on two factors: the methodological limitations of the individual studies contributing to a review finding and the coherence of each review finding.

Assessing methodological limitations: Findings that are drawn from well‐conducted studies can be regarded as more dependable (Lincoln 1985). We therefore appraised how well the individual studies which contributed to the evidence of a review finding were conducted, using an adaptation of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) quality‐assessment tool for qualitative studies (CASP 2006), as described above. When several studies with varied methodological limitations contributed to a finding, we made an overall judgment about the distribution of strengths and weaknesses in the studies to come to an assessment of the overall methodological limitations.

Assessing coherence: We assessed the coherence of each review finding by looking at the extent to which we were able to identify a clear pattern across the data contributed by each of the individual studies. This pattern could be assessed as clear in circumstances where the review finding was consistent across multiple contexts or where the review finding incorporated explanations for any variations across individual studies. The coherence of the review findings could be further strengthened where the individual studies contributing to the finding were drawn from a wide range of settings.

We assessed the certainty of each review finding as either high, moderate or low. A review finding drawn from generally well‐conducted studies with few methodological limitations – and showing high levels of coherence – was rated as high certainty. A review finding where there were concerns regarding either the methodological limitations of the studies or the coherence of the finding was assessed as moderate certainty. Where the studies had important methodological limitations and where there were concerns regarding the coherence of the review finding, this finding was assessed as being of low certainty.

CerQual is similar to GRADE (Guyatt 2011) in that both approaches aim to assess the certainty of (or confidence in) the evidence, and both also rate this certainty for each finding across studies rather than for each individual study. GRADE also bases its assessment on a combination of the quality of the evidence and other factors, including consistency across studies. However, GRADE is designed to assess the certainty of evidence regarding the effectiveness of an intervention, and is not suitable when appraising the certainty of qualitative evidence. The CerQual approach is also similar to an approach used by Goldsmith et al (Goldsmith 2007). In their synthesis of qualitative research, they assess the overall quality of the evidence for each individual finding by evaluating the quality, consistency and directness of the evidence. We have chosen not to refer to the directness of the evidence as it can be argued that, in the context of qualitative evidence syntheses, this dimension needs to be assessed by the end‐user of the evidence.

Data synthesis

We analysed and synthesised qualitative evidence using the framework thematic synthesis approach (Booth 2012). Thematic synthesis is one of several approaches recommended by the Cochrane Qualitative Review Methods Group (Noyes 2011) and may be particularly appropriate where evidence is likely to offer only thin description and is likely to be largely descriptive as opposed to highly theorised or conceptual. In the framework approach, the thematic synthesis is guided by an a priori theoretical framework. Framework synthesis has five stages:

Familiarisation: immersion in the included studies with the aims and objectives of the review.

Identifying a thematic framework: Rather than develop our own a priori framework after reading the included studies, we opted to use the SURE framework described above (The SURE Collaboration 2011) as an a priori framework of themes and categories. We used this framework to guide our analysis for two reasons. Firstly, it provided us with a comprehensive list of possible factors that could influence intervention implementation. Secondly, the current synthesis is one of four syntheses of qualitative research that have informed the World Health Organization's OPTIMIZEMNH Guidelines (WHO 2012). The use of the SURE Framework across these syntheses made it possible to carry out an overarching analysis of factors influencing optimisation among different health worker groups.

Indexing: Four review authors independently read and re‐read the selected studies and applied the SURE framework, moving between the data and the themes covered by the framework, but also searching for additional themes until all the studies had been reviewed. The definitions and boundaries of each of the emerging themes were discussed among the authors. The SURE framework was then revised in line with the ideas and categories that emerged.

Charting: We then developed the thematic synthesis further by rearranging data according to the appropriate part of the thematic framework to which they related, and formed charts. Our charts contained distilled summaries of evidence from different stakeholder perspectives and involved a high level of abstraction and synthesis. At the charting and mapping stage we used a cross‐case analysis approach (Miles 1994) to explore whether there were differences between high, middle and low income countries in the barriers and facilitators we identified, and whether studies of trained traditional birth attendants differed from studies of other types of lay health workers. Any differences that were identified were indicated in the text of the results.

Mapping and interpretation: Using the charts we then defined concepts, mapped the range and nature of phenomena, created typologies and found associations between themes as a way of developing explanations for the findings. The process of mapping and interpretation was influenced by the original review objectives as well as by the themes that have emerged from the data.

See Table 3 for an overview of the data synthesis process.

3. Data synthesis approach.

| Main elements of the data synthesis | Purpose | Tools and frameworks used |

| Identifying a theoretical model of barriers and facilitators to health systems intervention implementation | ‐ To inform the synthesis of the included studies ‐ To enable an overarching analysis across several syntheses of qualitative data within a broader, but relevant theme |

The SURE framework |

| Developing a synthesis of the included studies | ‐ To identify and list the barriers and facilitators to implementation reported ‐ To explore the relationships between reported barriers and facilitators |

Framework thematic synthesis |

| Exploring differences across contexts | ‐ To explore possible differences in barriers and facilitators between high, middle and low income countries and between studies of trained traditional birth attendants and other type of lay health workers | Cross case analysis |

| Assessing the certainty of the findings | ‐ To assess the quality of the individual studies ‐ To assess the certainty of the evidence for drawing conclusions about barriers and facilitators to lay health worker programme implementation |

Elements of the CASP tool CerQual tool |

| Integrating the findings of the synthesis with the Cochrane review of LHW programme effectiveness | ‐ To suggest how specific chains of activities and events identified in the synthesis of qualitative studies could lead to the outcomes described in the review of effectiveness | Logic model approach |

Summary of qualitative findings tables

After organising the data into themes and concepts, we summarised these findings in a summary of qualitative findings table. This table is similar to “Summary of Findings” tables used in Cochrane reviews of effectiveness and summarise the key findings and the certainty of evidence for each finding, and also provide an explanation of the assessment of the certainty of the qualitative evidence.

Parallel synthesis of the qualitative evidence and the intervention review

One of the objectives of the current synthesis was to integrate its findings with those of the effectiveness review. However, this type of integration is still a relatively novel approach without agreed‐upon standards or methods.

We decided to use a logic model approach to achieve this aim. The aim of a logic model is not to prove causal links between programme or policy elements and outcomes, but simply to present theories or assumptions about these links. There is no uniform template for developing logic models, although the most common approach involves identifying a logical flow that starts with specific planned inputs and activities and ends with specific outcomes or impacts, often with short‐term or intermediate outcomes along the way.

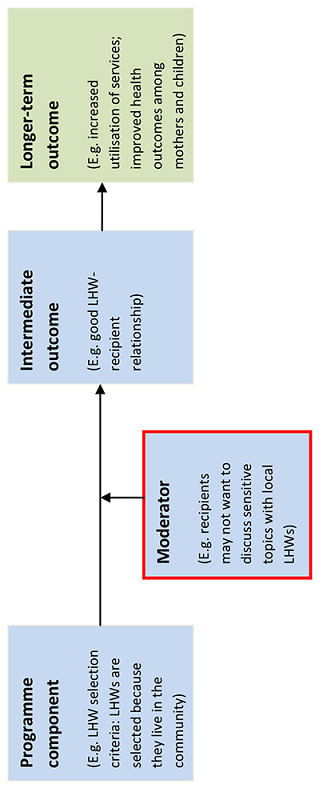

Two authors (CG, SL) went through the findings from the summary of qualitative findings table and organized these findings into several chains of events that we propose might ultimately lead to the outcomes explored in the effectiveness review. Firstly, we categorised findings from the qualitative synthesis and outcome measures from the effectiveness review as one of the following:

A component or planned element of the lay health worker programme (see Figure 2). All components were based on information from the synthesis of qualitative research.

2.

Example of a logic model chain

Anintermediate outcome that the components might lead to (see Figure 2). Intermediate outcomes were based on information from the synthesis of qualitative research or were based on outcome measures that had been identified a priori as relevant in the review of effectiveness.

Alonger‐term outcome that the components might ultimately lead to (see Figure 2). All longer‐term outcomes were based on outcome measures that had been identified a priori as relevant in the review of effectiveness.

Amoderator, i.e. a factor that could affect, either positively or negatively, the relationship between a component and the intermediate or longer term outcome (see Figure 2). All moderators were based on information from the synthesis of qualitative research.

We then organised these elements into chains of events. This was an iterative process, and we developed several versions before agreeing on the model. All authors then commented on the draft model before it was finalised.

In the final model, components, moderators and intermediate outcomes that were based on evidence from the qualitative synthesis were shaded blue. Intermediate outcomes and longer‐term outcomes that were taken from the effectiveness review were shaded green.

The process of categorising the findings in the qualitative synthesis as components, moderators or intermediate outcomes involved varying degrees of imputation. When describing programme components, we sometimes re‐phrased “negative” findings as “positive” findings. For instance, one of the findings states that lay health workers expressed frustration where payment differed across regions or institutions. We re‐phrased this in the logic model and presented “consistent lay health worker incentives” as a programme component. Moderators and intermediate outcomes also varied in the extent to which they were direct interpretations of the synthesis findings. For some, a degree of imputation was used. Where feasible, we have indicated which findings each element was base on by referring to the reference number of the relevant finding in the summary of qualitative findings table.

Results

Description of studies

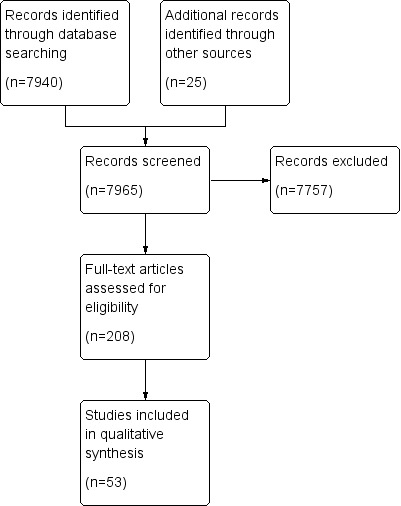

Results of the search

We identified a total of 7684 titles and abstracts and considered 179 full text papers for inclusion in this synthesis. Fifty‐three studies of LHW programmes, described in 56 papers, were included in the synthesis (Figure 3), 51 of which were published after 2000 (See Characteristics of included studies).

3.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Study respondents

In almost all of the studies, authors sought the perspectives of the LHWs themselves, although many studies also included programme recipients as respondents. Other respondents included health professionals working with the LHWs, programme staff, supervisors, community leaders and policy makers.

Setting

Seventeen of the LHW programmes were based in low income countries (Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Gambia, Kenya, Malawi, Nepal, Uganda, Viet Nam, Zambia, Zimbabwe); 19 programmes were based in middle income countries (Brazil, Ghana, Guatemala, Honduras, India, Iran, Mexico, Nicaragua, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, South Africa, Thailand); and 17 programmes were based in high income countries (Australia, Canada, USA, UK). These assignments are based on the World Bank’s 2011 classification (World Bank 2011).

Most of the programmes from high income countries took place in urban settings and recipients often belonged to particular social groups, such as immigrants or refugees, families living in temporary accommodation, or teenage mothers. The programmes from low and middle income countries took place in both urban and rural settings, although most were in rural settings, and recipients were generally regarded as particularly in need of more accessible healthcare services.

The programmes were run by either non‐government organisations (NGOs) or local and national governments, or a collaboration of these, and ranged from small pilot programmes to large‐scale national programmes.

In 42 of the programmes the LHWs delivered services to people in their homes, in the community, or in both homes and the community. In the remaining 11 programmes, LHWs delivered services in health facilities although often in combination with home or community‐based services.

Healthcare services

The healthcare services that LHWs delivered were generally poorly described and precise information was hard to obtain. LHWs provided services ranging from promotional and often relatively simple tasks to more complex sometimes curative tasks. LHW programmes from high income countries primarily provided promotional services. Where more complex, curative tasks were performed, or where medicines or contraceptives were distributed, this took place in low and middle income countries.

Promotion, counselling and support

In all of the studies from high income countries, as well as some studies from low and middle income countries, LHWs were used for promotion, counselling and support.

In six studies, the LHWs' main task was to offer breastfeeding advice and support. Four of these studies were from the UK (Beake 2005; Curtis 2007; Raine 2003) and the USA (Meier 2007), while two studies were from Uganda (Nankunda 2006) and South Africa (Daniels 2010). In the South African study, LHWs worked in the context of high HIV/AIDS prevalence and offered advice about both breastfeeding and bottle feeding in addition to promoting HIV testing and counselling.

In four USA‐based studies (Behnke 2002; Hazard 2009; Korfmacher 2002; Low 2006b), LHWs gave teenage mothers and others in difficult socioeconomic circumstances emotional and practical support, and promoted healthy behaviours during pregnancy, childbirth and in the first few weeks after birth. In Australia, LHWs offered emotional and practical support to parents at risk of child abuse and neglect (Taggart 2000).

In approximately 13 studies, from Australia (Downie 2004), Canada (Heaman 2006; Woodgate 2007), UK (Murphy 2008; Perkins 2001; Smith 2007), USA (Sheppard 2004; Warrick 1992), Brazil (Wayland 2002), Mexico (Ramirez‐Valles 2003), India (Alcock 2009), Papua New Guinea (Ashwell 2009) and Viet Nam (Hendrickson 2002), LHWs carried out a package of tasks that were primarily promotional, and mainly involved information and advice about topics such as family planning, pregnancy and childbirth, breastfeeding, vaccinations and other aspects of newborn and child health care.

In one Malawi‐based study (Mkandawire 2005), LHWs cared for people with chronic illnesses, including those with HIV/AIDs, assisting them with household chores, accompanying them to hospital, and offering HIV counselling. In another study, in South Africa (Malema 2010), LHWs offered counselling and testing as a way of preventing of mother to child transmission of HIV/AIDs.

Promotion and distribution

In one Kenyan study, LHWs promoted and sold iron supplements and other micronutrients (Suchdev 2010). In three studies, based in Kenya (Kaler 2001), Ethiopia (Mekonnen 2008) and Uganda (Siu 2009), LHWs offered information about family planning and reproductive health. In the Kenyan and Ethiopian studies, the LHWs also distributed family planning methods.

Diagnosis and treatment

In Ghana, LHWs diagnosed and treated children with uncomplicated malaria, and referred children on if the condition worsened or if severe malaria was suspected (Chinbuah 2006).

Packages of promotional, preventive and curative tasks

In many studies LHWs delivered packages of assigned tasks. However, these tasks were often poorly specified and the following descriptions of task packages only give an approximation of their contents.

In approximately 11 studies, from Bangladesh (Khan 1998; Rashid 2001; Simmons 1990), Brazil (Lancman 2009), Honduras (McQuestion 2010), Iran (Javanparast 2009), Nepal (Glenton 2010), Nicaragua (George 2009), Pakistan (Haq 2009), South Africa (Mathews 1994) and Thailand (Kaufmann 1997), LHWs carried out a package of tasks that were primarily promotional but that also included the delivery of preventive and curative healthcare interventions. These tasks included the distribution of contraceptives, iron supplements, vitamin A supplements, deworming tablets, polio vaccines, and tetanus vaccines to children or pregnant women; tuberculosis (TB) management; diagnosis and management of malnutrition; provision of first aid treatment for accidental wounds and injuries; and the diagnosis and treatment of common childhood illnesses, including diarrhoea and pneumonia.

In approximately 11 studies, from Bangladesh (Dynes 2011), Ethiopia (Sibley 2006), Gambia (bij de Vaate 2002), Guatemala (Hinojosa 2004; Maupin 2008), Honduras (Low 2006), Malawi (Bisika 2008), Pakistan (Islam 2001), Papua New Guinea (Bettiol 2004), Zambia (Ngoma 2009) and Zimbabwe (Mathole 2005), LHWs delivered a number of promotional tasks tied to maternal and child health care, but some, often traditional birth attendants, were also trained to manage uncomplicated labour and to detect high risk pregnancies and labour complications so that timely referral could be made.

Lay health worker (LHW) selection, training, supervision and incentives

Information about how the LHWs were selected was often lacking. However, with very few exceptions, LHWs were local women. About a third of the studies specified that the LHWs were expected to have either a secondary level education or some level of literacy, while in at least seven studies this was not a requirement and LHWs were often illiterate or only semi‐literate. Other common selection criteria were that the person should be respected and trusted in the community, should be married or have children, and should have particular personal traits such as communication skills, life experience, a willingness to learn, and an eagerness to work. In eight studies, the LHWs were traditional birth attendants from the community. The involvement of community members in the selection of the LHWs and in other aspects of the programmes was generally poorly described in the included studies. However, in at least 10 studies the community had been involved in the selection of LHWs.

Information about levels of training and supervision was also often lacking. Where this information was available, LHWs received between a few days and three months training, although two to three weeks, sometimes with refresher training, was most common. Information about levels of supervision and who provided this supervision was even less frequent, but in several cases supervision was provided by nurses or nurse‐midwives, often from the health facility to which the LHWs were attached.

Some information about incentives was given in about two‐thirds of the studies. In at least 11 studies, LHWs received some sort of direct financial compensation for the work they carried out, for instance through a fixed monthly salary or stipend, payment by the hour, or according to the number of women they had visited. This was most common in high income countries. In two studies, LHWs kept the profit from the supplements they had sold. In at least 17 studies, it appeared that LHWs were not salaried, although they often received other types of monetary and non‐monetary incentives, including lunch money, travel money, access to micro‐credit, childcare and bicycles. In three or four of these studies, there was some expectation that the LHWs would be paid in cash or kind by recipients or by the community, for instance the village development committee.

Risk of bias in included studies

We did not perform a risk of bias assessment for the included studies as this is not an appropriate method for qualitative research. Instead, we appraised the quality of each study and the certainty of the review findings using approaches deemed relevant for qualitative research.

The quality of the included qualitative studies

Almost all of the included studies were published as papers in health research journals, leading to word limitations not particularly well suited for reporting of qualitative research. In general, studies gave some description of the strategies they had used to select participants and to collect and analyse data, although these descriptions tended to be brief. Most of the studies used interview or focus group methods, with very few instances of long‐term ethnographic research. Few of the studies included any discussion of reflexivity. While we often assessed findings as being supported by the data, the descriptions of study context and the presentation of findings were relatively short. The general lack of 'thick description' may have been due to the choice of methods and the limitations set by the journals in which the studies were published (see also Table 2).

Certainty of the review findings

As described in the methods section, we used the CerQual approach to assess the certainty of each review finding, grading each finding as either of high, moderate or low certainty. None of the study findings were assessed to be of high certainty, because of weaknesses in study quality. We assessed a little less than half of the findings as of moderate certainty because the findings showed high levels of coherence, while we assessed a little more than half of the findings to be of low certainty because of concerns regarding both the coherence of the findings and the quality of the underlying studies.

Effects of interventions

Lay health worker (LHW) programme effectiveness has been assessed in another Cochrane review (Lewin 2013).

Here we present three analyses:

1. a framework synthesis, where we present the barriers and facilitators to the implementation of LHW programmes for maternal and child health;

2. a logic model, where we bring together the results of the qualitative and quantitative reviews;

3. an overview of hypotheses that are based on the logic model and that could serve as a basis for subgroup analyses in the review of LHW effectiveness.

1. The framework synthesis

Our first and main objective was to identify barriers and facilitators to LHW programme implementation. Our findings are presented here and are summarised in the summary of qualitative findings tables (Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Table 9).

4. Summary of qualitative findings, part 1.

| Summary statement | Certainty in the evidence | Explanation of certainty in the evidence assessment |

| Programme acceptability, appropriateness and feasibility: The lay health worker‐recipient relationship I | ||

| 1. Both programme recipients and LHWs emphasised the importance of trust, respect, kindness and empathy in the LHW‐recipient relationship. | Moderate certainty | In general, the studies were of moderate quality, and the finding was seen across several studies and settings. |

| 2. Recipients appreciated the similarities they saw between themselves and the LHWs. | Moderate certainty | In general, the studies were of moderate quality, and the finding was seen across several studies and settings. |

| 3. Some LHWs expressed an appreciation of the community‐based nature of the programmes, which allowed them a certain amount of flexibility in their working hours. | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the finding is only from two studies in Uganda and Nepal. |

| 4. LHWs were compared favourably with health professionals, whom recipients often regarded as less accessible, less friendly, more intimidating, and less respectful. | Moderate certainty | In general, the studies were of moderate quality, and the finding was seen across several studies and settings. |

| 5. Some recipients who had easy access to doctors indicated a preference for these health professionals. | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the finding is only from two studies in Thailand and Bangladesh. |

| 6. LHWs reported difficulties in managing emotional relationships and boundaries with recipients. | Moderate certainty | In general, the studies were of moderate quality, and the finding was seen across several studies and settings. |

| 7. Some recipients were concerned that home visits from LHWs might lead the LHWs to observe and share personal information or might lead neighbours to think recipients were HIV‐positive. | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the finding is only from three studies in USA and South Africa. |

| 8. LHWs, particularly those working in urban settings, reported difficulties maintaining personal safety when working in dangerous settings or at night. | Moderate certainty | In general, the studies were of moderate quality, and the finding was seen across several studies and settings, although predominantly in urban areas. |

| 9. In some settings, gender norms meant that female LHWs could not easily move within their community to fulfil their responsibilities. | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the finding is only from two studies in Bangladesh. |

| 10. Some LHWs feared the burden of responsibility and blame if interventions delivered to other community members were unsuccessful. | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the finding is only from two studies in Nepal and Kenya. |

5. Summary of qualitative findings, part 2.

| Summary statement | Certainty in the certainty | Explanation of certainty in the evidence assessment |

| Programme acceptability, appropriateness and feasibility: The lay health worker‐recipient relationship II | ||

| 1. Some recipients failed to utilize LHW services because of concerns about intervention safety or a lack of understanding about the programme or the benefits of the intervention. | Moderate certainty | In general, the studies were of moderate quality, and the finding was seen across several studies and settings. |

| 2. Some recipients failed to utilize LHW services because they could not afford these services. | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the finding is only from one study in Zambia. |

| 3. Recipients sometimes perceived LHW services as not relevant to their needs or not sufficient, particularly when services focused on promotional activities. | Moderate certainty | In general, the studies were of moderate quality, and the finding was seen across several studies and settings. |

| 4. Recipients’ and LHWs’ perceptions of the LHW services as not relevant or not sufficient could lead to feelings of impotence and demotivation among the LHWs. LHWs who primarily offered promotional and counselling services sometimes expressed a need to offer "real healthcare" in order to better respond to the expressed needs of the community. | Moderate certainty | In general, the studies were of moderate quality, and the finding was seen across several studies and settings. |

| 5. Recipients expressed confidence in the knowledge and skills of the LHWs and saw them as a useful source of information. | Moderate certainty | In general, the studies were of moderate quality, and the finding was seen across several studies and settings. |

| 6. LHW credibility was believed by different stakeholders to be heightened through visible ties to the health system. These ties were emphasised through, for example, LHWs’ possession of equipment and their ability to refer directly to clinics. | Moderate certainty | In general, the studies were of moderate quality, and the finding was seen across several studies and settings. |

| 7. Visible ties to the health system could enhance LHW credibility, but not always. In one study where community members had little respect for health professionals, LHWs attempted to disassociate themselves by emphasizing their status as unpaid volunteers. In another study, LHW credibility was questioned because they received payment. | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the finding is only from two studies in Nepal and South Africa. |

| 8. LHW credibility and acceptance was believed to be strengthened through the active support and participation of community leaders and community structures. However, the success of this type of involvement was seen as useful primarily where community leaders had authority and respect. | Moderate certainty | In general, the studies were of moderate quality, and the finding was seen across several studies and settings, although primarily in LMIC countries. |

| 9. LHW credibility and acceptance was believed to be strengthened through the active support and participation of family members involved in health decision‐making. | Moderate certainty | In general, the studies were of moderate quality, and the finding was seen across several studies and settings. |

| 10. Female LHWs and male family members sometimes found it embarrassing to communicate about family planning or HIV counselling. | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the finding is only from three studies in USA, Pakistan and South Africa. |

6. Summary of qualitative findings, part 3.

| Summary statement | Certainty in the evidence | Explanation of certainty in the evidence assessment | |

| Programme acceptability, appropriateness and feasibility: The lay health worker‐health professional relationship | |||

| 21. Where LHWs described good relationships with health professionals, they referred to these relationships as being respectful, supportive and egalitarian, and where LHWs were regarded as possessing complementary and valuable skills. | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the finding is only from three studies in Nicaragua, Canada and South Africa. | |

| 22. In studies where health professionals expressed appreciation of LHWs, they emphasised the LHWs’ contribution to the health professionals’ busy workload; their skills in communicating with the _target population and their knowledge and experience of the issues at hand; and their commitment and dedication to their patients and the community. | Moderate certainty | In general, the studies were of moderate quality, and the finding was seen across several studies and settings. | |

| 23. In studies describing poor relationships between LHWs and health professionals, LHWs were regarded as unequal, subservient, not part of the organisation, and LHWs complained of arrogance and lack of respect from health professionals. | Moderate certainty | In general, the studies were of moderate quality, and the finding was seen across several studies and settings. | |

| 24. In a few studies, health professionals described problems with working with LHWs. These health professionals pointed to the tension between being expected to function as partners, supervisors and evaluators, added workloads, and fear that they would lose authority. | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the finding was only from a few studies and settings. | |

| 25. Some studies suggested that the closer the collaboration was between the health professional and the LHW, the better the relationship was likely to be. | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the finding is only from three studies in Papua New Guinea, UK, and South Africa. | |

7. Summary of qualitative findings, part 4.

| Summary statement | Certainty in the evidence | Explanation of certainty in the evidence assessment | |

| Lay health worker motivation and incentives | |||

| 26. LHWs were driven by a wide range of inter‐connected motives, both intrinsic and extrinsic, including altruism and social engagement, social status and recognition, knowledge and skills gain, career development, and a general sense of empowerment. These motives were seen across a range of settings although the issue of social recognition appeared to be less common in HIC settings, where LHWs were often not from the same neighbourhood as their clients. | Moderate certainty | In general, the studies were of moderate quality, and the finding was seen across several studies and settings. | |

| 27. Some unsalaried LHWs expressed a strong wish for regular payment. | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the finding was only from two studies (Kenya, Uganda). | |

| 28. Some salaried LHWs were dissatisfied with their wages, believing that it did not reflect their abilities, their level of responsibility or their increase in skills as they acquired further training and education. | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the finding was only from four studies in UK, Canada, USA and South Africa. | |

| 29. Some volunteer LHWs and other stakeholders expressed concern that payment would change the dynamics of the LHW‐client relationship, threaten the LHWs’ social status or lead recipients to question the LHWs’ motives for delivering services. Some stakeholders underlined the importance of understanding what LHW motivations are in each context and the necessity of ensuring that the expectations of LHWs, programme managers and policy makers are in alignment. | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the finding was only from three studies in South Africa, Nepal and Australia. | |

| 30. Changes in tasks could influence expectations regarding incentives. For instance, while some LHWs were willing to work as volunteers when tasks could be done at their leisure, activities that demanded that they were present during labour and birth implied irregular and unpredictable working conditions, and led to demands for monetary incentives. | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the finding was only from one study in Nepal. | |

| 31. While regular salaries were not part of many programmes, other monetary and non‐monetary incentives, including payment to cover out‐of‐pocket expenses and “work tools” such as bicycles, uniforms or ID badges, were greatly appreciated by LHWs. | Moderate certainty | In general, the studies were of moderate quality, and the finding was seen across several studies and settings. | |

| 32. Some LHWs who received payment through selling drugs and supplements encountered problems including an inflated idea of the profit they would be making; people buying drugs on credit purchase basis or being reluctant to buy drugs because of their perception that the LHWs got the drugs for free; and competition from other vendors. | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the finding was only from two studies in Bangladesh and Kenya. | |

| 33. Some LHWs referred to frustration when payment differed from region to region or across different types of institutions. | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the finding was only from two studies in Nepal and Ethiopia. | |

| 34. Some LHWs and other stakeholders complained that there were few systems in place through which they could voice their individual or collective complaints about incentives or other issues. | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the finding was only from two studies (Iran, Nepal). | |

8. Summary of qualitative findings, part 5.

| Summary statement | Certainty in the evidence | Explanation of certainty in the evidence assessment | |||

| Lay health worker training, supervision and working conditions | |||||

| 35. LHWs highlighted aspects of training that they saw as positive including the use of practical demonstrations, picture cards and frequent refresher training. | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the finding was only from three studies in Gambia, South Africa and Ethiopia. | |||

| 36. In general, however, LHWs highlighted a number of weaknesses with current training, including schedules not flexible enough to respond to LHW turnover, poor quality and irrelevant training programmes and unskilled trainers. | Moderate certainty | In general, the studies were of moderate quality, and the finding was seen across several studies and settings. | |||

| 37. LHWs asked for more training in counselling and communication, a task which is often central to the role of the LHWs, but which they often found to be complex to perform. | Moderate certainty | In general, the studies were of moderate quality, and the finding was seen across several studies and settings. | |||

| 38. Some LHWs wanted training in topics outside of their current role, including common health problems, birth complications, sexual abuse and domestic violence, substance abuse and housing difficulties. These requests appeared to reflect the LHWs’ need to respond to the expressed needs of the community and to the circumstances they were confronted with in their work. | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the finding was only from four studies in USA, Thailand and Honduras. | |||

| 39. Supervision was seen as important by programme staff and LHWs for quality of intervention delivery, and as an opportunity to give and receive support, guidance and continued training; assess skills; and address ongoing challenges. Despite this acknowledgement of the importance of supervision, however, the studies pointed to a number of problems including supervisors’ lack of time, large distances, lack of transportation and lack of skills. | Moderate certainty | In general, the studies were of moderate quality, and the finding was seen across several studies and settings. | |||

| 40. A small number of studies described supervision that was perceived to be good. Here, supervisors displayed respect to the LHW; had a good understanding of the LHW’s working conditions and personal circumstances; provided emotional and technical support; and carried out plentiful field visits. | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the finding was only from a small number of studies and settings. | |||

| 41. In addition to formal supervision, some LHWs also appreciated the opportunity to share experiences with other LHWs | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the finding was only from two studies in USA and Australia. | |||

| 42. Both LHWs and supervisors in a number of studies expressed concern about the LHWs’ workload and the distances they had to cover, and LHWs sometimes found it difficult to carry out all of their tasks because of this. | Moderate certainty | In general, the studies were of moderate quality, and the finding was seen across several studies and settings. | |||

| 43. A few studies, mostly in LMICs, referred to poor working conditions, including inadequate lighting and small, dirty rooms, lack of supplies, too much paperwork, and high staff turnover. | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the finding was only from a small number of studies and settings. | |||

9. Summary of qualitative findings, part 6.

| Summary statement | Certainty in the certainty | Explanation of certainty in the evidence assessment |

| Patient flow processes | ||

| 44. LHWs in a number of studies were trained to refer patients with complications on to health professionals. However, health professionals in one study were concerned that trained TBAs were over‐confident about their ability to manage danger signs or lacked the knowledge to recognise such signs. Overconfidence was also suggested by authors of another study as a reason for poor compliance among LHWs who were meant to refer children with malaria on. | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the finding was only from two studies in Malawi and Gambia. |

| 45. The LHWs themselves and their recipients pointed to different factors that made referral difficult to those highlighted by health professionals. Some trained TBAs and recipients pointed out that referral was made difficult by a lack of health professionals to refer patients to. | Low certainty | The studies were of moderate quality. However, the findings were only from two studies in Pakistan and Honduras. |