In December, 2019, Wuhan, Hubei province, China, became the centre of an outbreak of pneumonia of unknown cause, which raised intense attention not only within China but internationally. Chinese health authorities did an immediate investigation to characterise and control the disease, including isolation of people suspected to have the disease, close monitoring of contacts, epidemiological and clinical data collection from patients, and development of diagnostic and treatment procedures. By Jan 7, 2020, Chinese scientists had isolated a novel coronavirus (CoV) from patients in Wuhan. The genetic sequence of the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) enabled the rapid development of point-of-care real-time RT-PCR diagnostic tests specific for 2019-nCoV (based on full genome sequence data on the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data [GISAID] platform). Cases of 2019-nCoV are no longer limited to Wuhan. Nine exported cases of 2019-nCoV infection have been reported in Thailand, Japan, Korea, the USA, Vietnam, and Singapore to date, and further dissemination through air travel is likely.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 As of Jan 23, 2020, confirmed cases were consecutively reported in 32 provinces, municipalities, and special administrative regions in China, including Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan.3 These cases detected outside Wuhan, together with the detection of infection in at least one household cluster—reported by Jasper Fuk-Woo Chan and colleagues6 in The Lancet—and the recently documented infections in health-care workers caring for patients with 2019-nCoV indicate human-to-human transmission and thus the risk of much wider spread of the disease. As of Jan 23, 2020, a total of 835 cases with laboratory-confirmed 2019-nCoV infection have been detected in China, of whom 25 have died and 93% remain in hospital (figure ).3

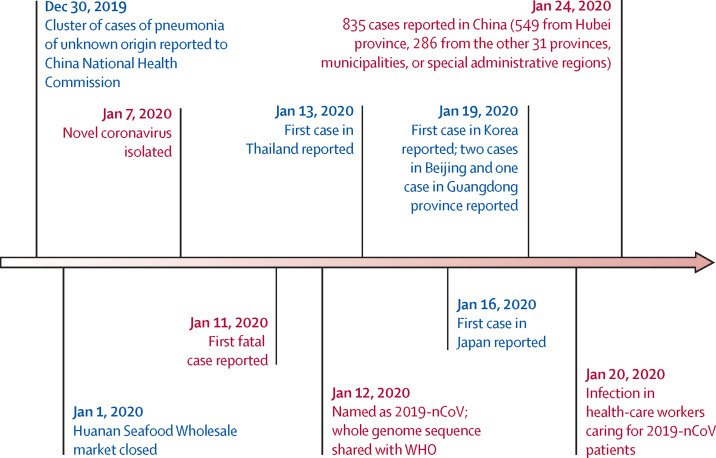

Figure.

Timeline of early stages of 2019-nCoV outbreak

2019-nCoV=2019 novel coronavirus.

In The Lancet, Chaolin Huang and colleagues7 report clinical features of the first 41 patients admitted to the designated hospital in Wuhan who were confirmed to be infected with 2019-nCoV by Jan 2, 2020. The study findings provide first-hand data about severity of the emerging 2019-nCoV infection. Symptoms resulting from 2019-nCoV infection at the prodromal phase, including fever, dry cough, and malaise, are non-specific. Unlike human coronavirus infections, upper respiratory symptoms are notably infrequent. Intestinal presentations observed with SARS also appear to be uncommon, although two of six cases reported by Chan and colleagues had diarrhoea.6 Common laboratory findings on admission to hospital include lymphopenia and bilateral ground-glass opacity or consolidation in chest CT scans. These clinical presentations confounded early detection of infected cases, especially against a background of ongoing influenza and circulation of other respiratory viruses. Exposure history to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale market served as an important clue at the early stage, yet its value has decreased as more secondary and tertiary cases have appeared.

Of the 41 patients in this cohort, 22 (55%) developed severe dyspnoea and 13 (32%) required admission to an intensive care unit, and six died.7 Hence, the case-fatality proportion in this cohort is approximately 14·6%, and the overall case fatality proportion appears to be closer to 3% (table ). However, both of these estimates should be treated with great caution because not all patients have concluded their illness (ie, recovered or died) and the true number of infections and full disease spectrum are unknown. Importantly, in emerging viral infection outbreaks the case-fatality ratio is often overestimated in the early stages because case detection is highly biased towards the more severe cases. As further data on the spectrum of mild or asymptomatic infection becomes available, one case of which was documented by Chan and colleagues,6 the case-fatality ratio is likely to decrease. Nevertheless, the 1918 influenza pandemic is estimated to have had a case-fatality ratio of less than 5%13 but had an enormous impact due to widespread transmission, so there is no room for complacency.

Table.

Characteristics of patients who have been infected with 2019-nCoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV7, 8, 10, 11, 12

| 2019-nCoV* | MERS-CoV | SARS-CoV | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||||

| Date | December, 2019 | June, 2012 | November, 2002 | |

| Location of first detection | Wuhan, China | Jeddah, Saudi Arabia | Guangdong, China | |

| Age, years (range) | 49 (21–76) | 56 (14–94) | 39·9 (1–91) | |

| Male:female sex ratio | 2·7:1 | 3·3:1 | 1:1·25 | |

| Confirmed cases | 835† | 2494 | 8096 | |

| Mortality | 25† (2·9%) | 858 (37%) | 744 (10%) | |

| Health-care workers | 16‡ | 9·8% | 23·1% | |

| Symptoms | ||||

| Fever | 40 (98%) | 98% | 99–100% | |

| Dry cough | 31 (76%) | 47% | 29–75% | |

| Dyspnoea | 22 (55%) | 72% | 40–42% | |

| Diarrhoea | 1 (3%) | 26% | 20–25% | |

| Sore throat | 0 | 21% | 13–25% | |

| Ventilatory support | 9·8% | 80% | 14–20% | |

Data are n, age (range), or n (%) unless otherwise stated. 2019-nCoV=2019 novel coronavirus. MERS-CoV=Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. SARS-CoV=severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus.

Demographics and symptoms for 2019-nCoV infection are based on data from the first 41 patients reported by Chaolin Huang and colleagues (admitted before Jan 2, 2020).8 Case numbers and mortalities are updated up to Jan 21, 2020) as disclosed by the Chinese Health Commission.

Data as of Jan 23, 2020.

Data as of Jan 21, 2020.9

As an RNA virus, 2019-nCoV still has the inherent feature of a high mutation rate, although like other coronaviruses the mutation rate might be somewhat lower than other RNA viruses because of its genome-encoded exonuclease. This aspect provides the possibility for this newly introduced zoonotic viral pathogen to adapt to become more efficiently transmitted from person to person and possibly become more virulent.

Two previous coronavirus outbreaks had been reported in the 21st century. The clinical features of 2019-nCoV, in comparison with SARS-CoV and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)-CoV, are summarised in the table. The ongoing 2019-nCoV outbreak has undoubtedly caused the memories of the SARS-CoV outbreak starting 17 years ago to resurface in many people. In November, 2002, clusters of pneumonia of unknown cause were reported in Guangdong province, China, now known as the SARS-CoV outbreak. The number of cases of SARS increased substantially in the next year in China and later spread globally,14 infecting at least 8096 people and causing 774 deaths.12 The international spread of SARS-CoV in 2003 was attributed to its strong transmission ability under specific circumstances and the insufficient preparedness and implementation of infection control practices. Chinese public health and scientific capabilities have been greatly transformed since 2003. An efficient system is ready for monitoring and responding to infectious disease outbreaks and the 2019-nCoV pneumonia has been quickly added to the Notifiable Communicable Disease List and given the highest priority by Chinese health authorities.

The increasing number of cases and widening geographical spread of the disease raise grave concerns about the future trajectory of the outbreak, especially with the Chinese Lunar New Year quickly approaching. Under normal circumstances, an estimated 3 billion trips would be made in the Spring Festival travel rush this year, with 15 million trips happening in Wuhan. The virus might further spread to other places during this festival period and cause epidemics, especially if it has acquired the ability to efficiently transmit from person to person.

Consequently, the 2019-nCoV outbreak has led to implementation of extraordinary public health measures to reduce further spread of the virus within China and elsewhere. Although WHO has not recommended any international travelling restrictions so far,15 the local government in Wuhan announced on Jan 23, 2020, the suspension of public transportation, with closure of airports, railway stations, and highways in the city, to prevent further disease transmission.16 Further efforts in travel restriction might follow. Active surveillance for new cases and close monitoring of their contacts are being implemented. To improve detection efficiency, front-line clinics, apart from local centres for disease control and prevention, should be armed with validated point-of-care diagnostic kits.

Rapid information disclosure is a top priority for disease control and prevention. A daily press release system has been established in China to ensure effective and efficient disclosure of epidemic information. Education campaigns should be launched to promote precautions for travellers, including frequent hand-washing, cough etiquette, and use of personal protection equipment (eg, masks) when visiting public places. Also, the general public should be motivated to report fever and other risk factors for coronavirus infection, including travel history to affected area and close contacts with confirmed or suspected cases.

Considering that substantial numbers of patients with SARS and MERS were infected in health-care settings, precautions need to be taken to prevent nosocomial spread of the virus. Unfortunately, 16 health-care workers, some of whom were working in the same ward, have been confirmed to be infected with 2019-nCoV to date, although the routes of transmission and the possible role of so-called super-spreaders remain to be clarified.9 Epidemiological studies need to be done to assess risk factors for infection in health-care personnel and quantify potential subclinical or asymptomatic infections. Notably, the transmission of SARS-CoV was eventually halted by public health measures including elimination of nosocomial infections. We need to be wary of the current outbreak turning into a sustained epidemic or even a pandemic.

The availability of the virus' genetic sequence and initial data on the epidemiology and clinical consequences of the 2019-nCoV infections are only the first steps to understanding the threat posed by this pathogen. Many important questions remain unanswered, including its origin, extent, and duration of transmission in humans, ability to infect other animal hosts, and the spectrum and pathogenesis of human infections. Characterising viral isolates from successive generations of human infections will be key to updating diagnostics and assessing viral evolution. Beyond supportive care,17 no specific coronavirus antivirals or vaccines of proven efficacy in humans exist, although clinical trials of both are ongoing for MERS-CoV and one controlled trial of ritonavir-boosted lopinavir monotherapy has been launched for 2019-nCoV (ChiCTR2000029308). Future animal model and clinical studies should focus on assessing the effectiveness and safety of promising antiviral drugs, monoclonal and polyclonal neutralising antibody products, and therapeutics directed against immunopathologic host responses.

We have to be aware of the challenge and concerns brought by 2019-nCoV to our community. Every effort should be given to understand and control the disease, and the time to act is now.

This online publication has been corrected. The corrected version first appeared at thelancet.com on January 29, 2020

Acknowledgments

FGH reports personal fees from University of Alabama Antiviral Drug Discovery and Development Consortium, and is a non-compensated consultant for Gilead Sciences, Regeneron, and SAB Biotherapeutics, which have investigational therapeutics for coronavirus infections. All other authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.WHO Novel coronavirus – Thailand (ex-China). Geneva: World Health Organization. Jan 14, 2020. https://www.who.int/csr/don/14-january-2020-novel-coronavirus-thailand/en/

- 2.WHO Novel Coronavirus – Japan (ex-China). Geneva: World Health Organization. Jan 16, 2020. https://www.who.int/csr/don/16-january-2020-novel-coronavirus-japan-ex-china/en/

- 3.China National Health Commission Update on the novel coronavirus pneumonia outbreak (Jan 24, 2020). Beijing: China National Health Commission. 2020. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/yqfkdt/202001/c5da49c4c5bf4bcfb320ec2036480627.shtml

- 4.WHO Novel coronavirus – Republic of Korea (ex-China). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2020. https://www.who.int/csr/don/21-january-2020-novel-coronavirus-republic-of-korea-ex-china/en/

- 5.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention First travel-related case of 2019 novel coronavirus detected in United States. Atlanta, GA: US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p0121-novel-coronavirus-travel-case.html

- 6.Chan JF-W, Yuan S, Kok K-H. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. published online Jan 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. published online Jan 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leung GM, Hedley AJ, Ho LM. The epidemiology of severe acute respiratory syndrome in the 2003 Hong Kong epidemic: an analysis of all 1755 patients. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:662–673. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-9-200411020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) situation report - 2 (22 January 2020). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200122-sitrep-2-2019-ncov.pdf

- 10.WHO Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2020. http://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/

- 11.Assiri A, Al-Tawfiq JA, Al-Rabeeah AA. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:752–761. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70204-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO Summary of probable SARS cases with onset of illness from 1 November 2002 to 31 July 2003. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2004. http://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/table2004_04_21/en/

- 13.Viboud C, Eisenstein J, Reid AH, Janczewski TA, Morens DM, Taubenberger JK. Age- and sex-specific mortality associated with the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic in Kentucky. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:721–729. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhong NS, Zheng BJ, Li YM. Epidemiology and cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Guangdong, People's Republic of China, in February, 2003. Lancet. 2003;362:1353–1358. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14630-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO Statement on the meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Geneva, World Health Organization. Jan 23, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/23-01-2020-statement-on-the-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov)

- 16.Announcement from the Headquarter for novel coronavirus pneumonia prevention and control (No 1). Beijing: China National Health Commission. 2020. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-01/23/content_5471751.htm

- 17.WHO Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected. Geneva, World Health Organization. 2020. https://www.who.int/internal-publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected