Abstract

Aims

To compare the efficacy and safety of new insulin glargine 300 U/ml (Gla‐300) with insulin glargine 100 U/ml (Gla‐100) over 12 months of treatment in people with type 2 diabetes using basal insulin and oral antihyperglycaemic drugs (OADs).

Methods

EDITION 2 (NCT01499095) was a randomized, 6‐month, multicentre, open‐label, two‐arm, phase IIIa study investigating once‐daily Gla‐300 versus Gla‐100, plus OADs (excluding sulphonylureas), with a 6‐month safety extension.

Results

Similar numbers of participants in each group completed 12 months of treatment [Gla‐300, 315 participants (78%); Gla‐100, 314 participants (77%)]. The reduction in glycated haemoglobin was maintained for 12 months with both treatments: least squares (LS) mean (standard error) change from baseline −0.55 (0.06)% for Gla‐300 and −0.50 (0.06)% for Gla‐100; LS mean difference −0.06 [95% confidence interval (CI) −0.22 to 0.10)%]. A significant relative reduction of 37% in the annualized rate of nocturnal confirmed [≤3.9 mmol/l (≤70 mg/dl)] or severe hypoglycaemia was observed with Gla‐300 compared with Gla‐100: rate ratio 0.63 [(95% CI 0.42–0.96); p = 0.031], and fewer participants experienced ≥1 event [relative risk 0.84 (95% CI 0.71–0.99)]. Severe hypoglycaemia was infrequent. Weight gain was significantly lower with Gla‐300 than Gla‐100 [LS mean difference −0.7 (95% CI −1.3 to −0.2) kg; p = 0.009]. Both treatments were well tolerated with a similar pattern of adverse events (incidence of 69 and 60% in the Gla‐300 and Gla‐100 groups).

Conclusions

In people with type 2 diabetes treated with Gla‐300 or Gla‐100, and non‐sulphonylurea OADs, glycaemic control was sustained over 12 months, with less nocturnal hypoglycaemia in the Gla‐300 group.

Keywords: basal insulin, insulin glargine, oral antihyperglycaemic drugs, type 2 diabetes

Introduction

New insulin glargine 300 U/ml (Gla‐300) has a more constant and prolonged pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) profile compared with insulin glargine 100 U/ml (Gla‐100) 1. The longer duration of action of Gla‐300 could provide effective 24‐h glycaemic control with once‐daily dosing, while allowing flexibility in injection time. In addition, the more even PK/PD profile may reduce the risk of hypoglycaemia, a key barrier to initiation and intensification of insulin therapy 2.

To investigate treatment outcomes with Gla‐300, a programme of clinical studies (the EDITION programme) was conducted in people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. Similar glycaemic control, recorded as change in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), with a lower risk of hypoglycaemia, was observed with Gla‐300 compared with Gla‐100 during the main 6‐month treatment periods of the EDITION 1, 2 and 3 studies, conducted in people with type 2 diabetes 3, 4, 5. During the main 6‐month treatment period of EDITION 2 (NCT01499095), which enrolled people with type 2 diabetes who were using basal insulin and oral antihyperglycaemic drugs (OADs), the relative risk of nocturnal confirmed [≤3.9 mmol/l (≤70 mg/dl)] or severe hypoglycaemia was 29% lower with Gla‐300 than with Gla‐100 3. Similarly, fewer participants experienced one or more confirmed or severe hypoglycaemic event at any time (24 h) with Gla‐300 than with Gla‐100. The annualized rates of confirmed or severe hypoglycaemic events were also lower with Gla‐300 than with Gla‐100. Weight gain was low, with statistically (p = 0.015) lower weight gain observed with Gla‐300 compared with Gla‐100 at 6 months.

After the main 6‐month treatment period, participants in EDITION 2 continued in a 6‐month safety extension to examine the longer‐term outcomes of treatment with Gla‐300 in people with type 2 diabetes using basal insulin and OADs. The 12‐month results of the EDITION 2 study are reported in the present paper.

Participants and Methods

Study Design and Participants

EDITION 2 (NCT01499095) was a multicentre, multinational, randomized, open‐label, two‐arm, parallel‐group, phase IIIa study conducted between 14 December 2011 and 26 April 2013 in 13 countries (two in North America, eight European countries and Chile, Mexico and South Africa). The protocol and study design have been described previously 3. Adults (aged ≥18 years old) with type 2 diabetes treated with ≥42 U/day basal insulin (Gla‐100 or NPH insulin) and OADs (except sulphonylureas) were randomized 1 : 1 to receive Gla‐300 or Gla‐100 for 6 months, with a 6‐month safety extension period 3. Exclusion criteria included: HbA1c <7.0 or >10%; recent (within the past 3 months) use of premixed insulin, insulin detemir or initiation of new glucose‐lowering agents; recent (within the past 2 months) use of sulphonylurea; recent (>10 days in the past 3 months) use of human regular insulin or mealtime insulin; and rapidly progressing diabetic retinopathy, end‐stage renal disease (defined as requiring dialysis or transplantation 6), or clinically significant cardiac, hepatic or other systemic disease. Gla‐300 (using a modified SoloSTAR® pen, sanofi‐aventis U.S. L.L.C., Bridgewater, NJ, USA) or Gla‐100 (using a SoloSTAR® pen) was self‐administered once daily at the same time each day in the evening, defined as the time immediately before the evening meal until bedtime. The insulin dose was to be titrated based on fasting self‐monitored plasma glucose (SMPG) values, according to a prespecified titration algorithm, seeking an SMPG _target of 4.4–5.6 mmol/l (80–100 mg/dl). Irrespective of treatment allocation, rescue treatment with a new antihyperglycaemic drug was allowed if the fasting plasma glucose (FPG) or HbA1c levels were above _target values and there was no reasonable explanation for insufficient glucose control, or if appropriate action failed to decrease the levels to below threshold values. The choice of rescue therapy (rapid insulin or other antihyperglycaemic medications) was based on the investigator's decision and local approved guidelines.

The protocol was approved by local or national ethics committees, and the study was conducted according to Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent.

Efficacy and Safety Analyses

Efficacy analyses included change in HbA1c, FPG, SMPG and daily basal insulin dose from baseline to the end of 12 months' treatment. Hypoglycaemic events were recorded using American Diabetes Association definitions 7. Severe hypoglycaemia and hypoglycaemia confirmed by an SMPG reading [symptomatic or asymptomatic, confirmed using a plasma glucose threshold of ≤3.9 mmol/l (≤70 mg/dl)] were reported in a composite category of confirmed or severe hypoglycaemia. A more stringent plasma glucose threshold of <3.0 mmol/l (<54 mg/dl) was also used. Severe hypoglycaemia was defined as an event requiring the assistance of another person to administer carbohydrate or glucagon or take resuscitative actions. Each category of hypoglycaemia was analysed as the percentage of participants reporting at least one event and as events per participant‐year (annualized rate). Hypoglycaemic events were analysed by occurrence at any time (24 h) and during the night (nocturnal; 00:00–05:59 hours). Change in body weight was assessed as a safety outcome. Adverse events (AEs), including injection site and hypersensitivity reactions, were recorded during the whole study period. Standard safety laboratory assessments for anti‐insulin antibodies (status, titre and cross‐reactivity with human insulin) were performed. The Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire status (DTSQs) was used to assess participant satisfaction with current treatment, including Perceived Frequency of Hyperglycaemia (item 2 of the DTSQs) and Perceived Frequency of Hypoglycaemia (item 3 of the DTSQs) 8, 9.

Data Analysis and Statistics

The modified intention‐to‐treat (mITT) population was defined as all randomized participants who received at least one dose of study insulin and had both a baseline and at least one post‐baseline primary or secondary efficacy endpoint assessment. Analyses of glycaemic control used the mITT population. A mixed‐effects model for repeated measures, conducted on rescue‐free measurements, was used to analyse HbA1c and FPG. Descriptive analyses were performed on dose and eight‐point SMPG.

Safety analyses included all participants randomized and exposed to at least one dose of study insulin. Hypoglycaemic event rates were analysed using an overdispersed Poisson regression model. Body weight and insulin dose were analysed using an analysis of covariance model. AEs were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) system.

Results

Study Population

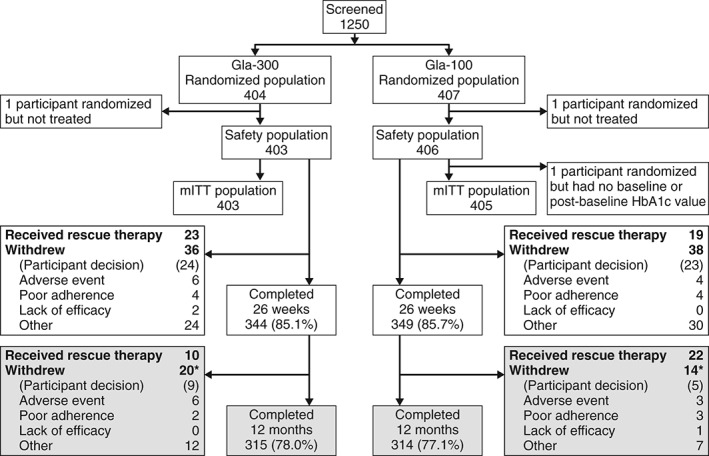

Of the 811 randomized participants, 404 were assigned to Gla‐300 and 407 to Gla‐100. In each group, 1 participant was randomized but not treated, and a further participant in the Gla‐100 group was randomized but did not have a baseline or post‐baseline primary or secondary efficacy endpoint measurement. These participants were excluded from the mITT population (Figure 1). A total of 315/404 (78%) and 314/407 (77%) participants in the Gla‐300 and Gla‐100 groups, respectively, completed 12 months of treatment (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow. *One participant in each group received rescue therapy and withdrew from the study. The upper portion with open boxes shows participant flow during the main 6‐month study period; the lower portion with shaded boxes shows flow during the extension phase up to month 12. Gla‐100, insulin glargine 100 U/ml; Gla‐300, insulin glargine 300 U/ml; mITT, modified intention‐to‐treat.

Baseline characteristics have been reported previously and were similar in the Gla‐300 and Gla‐100 groups 3. Participants had a mean [standard deviation (s.d.)] age of 58 (9.2) years, a mean (s.d.) body mass index (BMI) of 35 (6.4) kg/m2 and a mean (s.d.) duration of diabetes of 12.6 (7.0) years. Their mean (s.d.) HbA1c concentration was 8.24 (0.82)% [66.5 (9.0) mmol/mol], FPG concentration 8.0 (2.8) mmol/l [144.7 (51.0) mg/dl] and basal insulin dosage 0.67 (0.24) U/kg/day.

Almost all participants used biguanides in the Gla‐300 and Gla‐100 groups, both before the start of treatment [389/404 participants (96.3%) and 383/407 participants (94.1%), respectively] and during the on‐treatment period [385/404 participants (95.3%) and 381/407 participants (93.6%), respectively]. Dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitors were used before treatment and during the treatment period by 33 participants (8.2%) and 34 participants (8.4%), respectively, in the Gla‐300 group, and by 51 participants (12.5%) and 54 participants (13.3%), respectively, in the Gla‐100 group. Sulphonylureas had been used in the 3 months before randomization by 32 (3.9%) of all randomized participants. Overall, 16 (2.0%) participants used sulphonylureas during the study, including use as rescue therapy by 2 participants in the Gla‐300 group and 1 participant in the Gla‐100 group. During the 12‐month on‐treatment period, 33 participants (8.2%) in the Gla‐300 group and 41 (10.1%) in the Gla‐100 group received rescue therapy; relative risk 0.81 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.52–1.25; Figure 1], most commonly as rapid‐acting insulin.

Insulin Dose and Glycaemic Control (mITT Population)

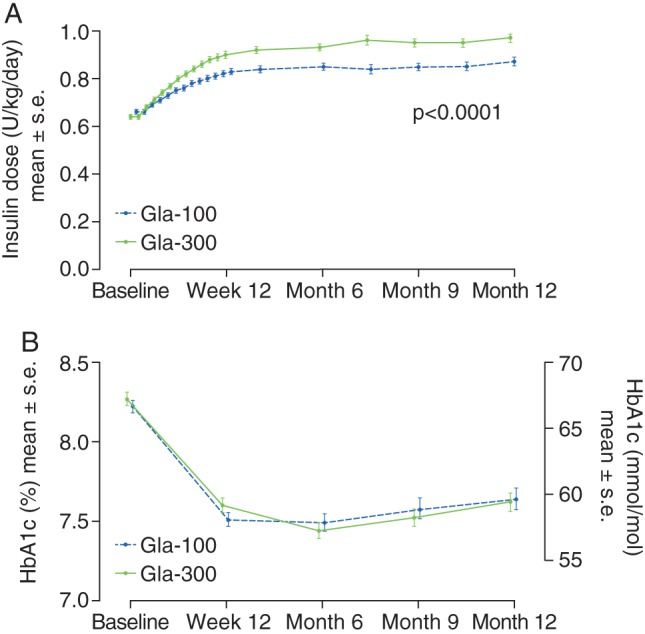

Over the whole 12‐month study period, the mean basal insulin dosage increased in both groups, primarily during the first 12 weeks and to a greater extent in the Gla‐300 group than the Gla‐100 group (Figure 2A). The mean basal insulin dosage continued to increase gradually up to month 12 in both treatment groups, reaching 0.97 U/kg/day in the Gla‐300 group and 0.87 U/kg/day in the Gla‐100 group [mean (standard error) difference 0.11 (0.02) U/kg/day; p < 0.0001].

Figure 2.

(A) Mean daily basal insulin dose (B) glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) ± standard error by visit (modified intention‐to‐treat population). Gla‐100, insulin glargine 100 U/ml; Gla‐300, insulin glargine 300 U/ml; s.e., standard error.

The mean HbA1c decreased from baseline to month 12 to a similar extent in each of the two treatment groups, with the greatest decrease occurring between baseline and week 12 in both groups (Figure S1A). The mean (s.d.) HbA1c at month 12 was 7.62 (1.03)% [59.8 (11.3) mmol/mol] in the Gla‐300 group and 7.64 (1.21)% [60.0 (13.2) mmol/mol] in the Gla‐100 group (Figure 2B). The least squares (LS) mean difference in change from baseline to month 12 between groups was −0.06 (95% CI −0.22 to 0.10)% [−0.66 (95% CI −2.4 to 1.1) mmol/mol].

In addition, FPG decreased to a similar extent in the two treatment groups, primarily during the initial 12 weeks of treatment, remaining relatively stable during the remainder of the 12‐month study period (Figure S1B). The LS mean difference in FPG change from baseline to month 12 between the groups was 0.18 (95% CI −0.21 to 0.57) mmol/l [3.3 (95% CI −3.7 to 10.3) mg/dl].

The mean eight‐point SMPG profiles decreased from baseline to month 12 in both treatment groups at all time points. At month 12, mean plasma glucose levels were similar in the two treatment groups from 03:00 hours to post‐lunch, but numerically lower in the Gla‐300 group than in the Gla‐100 group from pre‐dinner to bedtime (Figure S1C).

Hypoglycaemia (Safety Population)

Nocturnal Hypoglycaemia

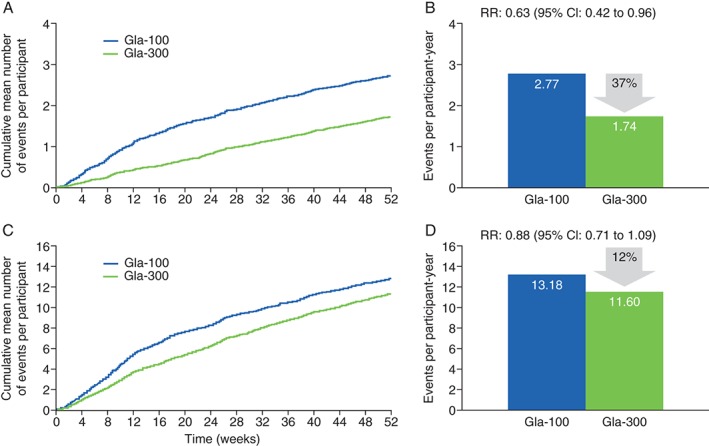

The cumulative mean number of nocturnal (00:00–05:59 hours) confirmed [≤3.9 mmol/l (≤70 mg/dl)] or severe hypoglycaemic events per participant is reported in Figure 3A. There was a significant 37% relative reduction in annualized rate with Gla‐300 compared with Gla‐100 [1.74 vs 2.77, rate ratio 0.63 (95% CI 0.42–0.96); p = 0.0308; Figure 3B], and a 16% relative risk reduction in the percentage of participants experiencing ≥1 nocturnal confirmed or severe hypoglycaemic event during the 12‐month study period [38% vs 45%, relative risk 0.84 (95% CI 0.71–0.99); Table S1].

Figure 3.

Confirmed [≤3.9 mmol/l (≤70 mg/dl)] or severe hypoglycaemia. (A) Cumulative mean number of nocturnal (00:00–05:59 hours) events per participant. (B) Nocturnal events per participant‐year. (C) Cumulative mean number of events per participant at any time (24 h). (D) Events per participant‐year at any time (24 h; safety population). CI, confidence interval; Gla‐100, insulin glargine 100 U/ml; Gla‐300, insulin glargine 300 U/ml; RR, rate ratio.

Considering all hypoglycaemia, there were fewer nocturnal hypoglycaemic events reported with Gla‐300 (668 events or 1.8 events per participant‐year) versus Gla‐100 [1110 events or 2.9 events per participant‐year; rate ratio 0.61 (95% CI 0.41–0.92); Table S1]. A total of 160 participants (40%) in the Gla‐300 group and 187 participants (46%) in the Gla‐100 group experienced at least one nocturnal hypoglycaemic event [relative risk 0.86 (95% CI 0.73–1.01)]. Annualized event rates and percentages of participants experiencing at least one event for these and other categories of hypoglycaemia during the night are shown in Table S1.

Hypoglycaemia at Any Time

The cumulative mean number of confirmed or severe hypoglycaemic events per participant at any time (24 h) is reported in Figure 3C. The annualized event rate (Figure 3D) and the percentage of participants with at least one event during 12 months of treatment were numerically lower but not significantly different with Gla‐300 compared with Gla‐100. Annualized rates of confirmed or severe hypoglycemia were 11.6 for Gla‐300 and 13.2 for Gla‐100, and the corresponding percentages of participants with at least one event were 78% for Gla‐300 and 82% for Gla‐100 (Table S1).

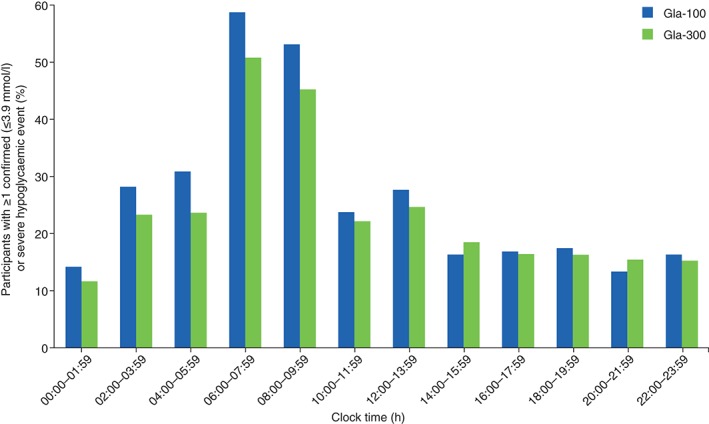

Over the 24‐h period, the percentage of participants reporting confirmed or severe hypoglycaemia tended to be lower in the Gla‐300 group than in the Gla‐100 group between 00:00 and 14:00 hours, and was similar in the two groups from 14:00 hours until midnight (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Percentage of participants with ≥1 confirmed [≤3.9 mmol/l (≤70 mg/dl)] or severe hypoglycaemic event during the 12‐month study on‐treatment period by time of day. Gla‐100, insulin glargine 100 U/ml; Gla‐300, insulin glargine 300 U/ml.

Other categories of hypoglycaemia, expressed as annualized event rates and percentages of participants experiencing at least one event at any time (24 h) are shown in Table S1.

Severe Hypoglycaemia

During the 12‐month study period, severe hypoglycaemia at any time (24 h) was reported by 7 (1.7%) participants (10 events) in the Gla‐300 group and 6 (1.5%) participants (13 events) in the Gla‐100 group, corresponding to a rate of 0.03 events per participant‐year in both treatment groups (Table S1). Three participants reported severe nocturnal hypoglycaemic events [1 participant (0.2%) using Gla‐300 and 2 participants (0.5%) using Gla‐100].

Body Weight

The significant between‐group weight difference observed at 6 months was maintained at 12 months of treatment (Figure S2) 3. The mean (s.d.) change in body weight, based on the last on‐treatment value, was significantly lower with Gla‐300 than with Gla‐100 [0.4 (4.1) vs 1.2 (3.6) kg]; the LS mean difference between groups at month 12 was −0.7 (95% CI −1.3 to −0.2) kg; p = 0.009.

Treatment Satisfaction

Participants in both treatment groups reported high satisfaction throughout the study; DTSQs treatment satisfaction scores were similar in each group. The improvement in DTSQs scores observed at month 6 was maintained at month 12, resulting in an overall mean (s.d.) increase from baseline to month 12 of 4.3 (6.6) with Gla‐300 and 4.4 (7.5) with Gla‐100. Perceived frequency of hypoglycaemia remained stable with either treatment [mean (s.d.) change from baseline to month 12, 0.05 (1.86) in both treatment groups]. Perceived frequency of hyperglycaemia slightly decreased in both treatment groups [mean (s.d.) change from baseline to month 12, −1.38 (2.18) and −1.37 (2.29) for Gla‐300 and Gla‐100, respectively].

Adverse Events

There was a similar pattern of treatment‐emergent AEs (TEAEs) in each treatment group, with incidences of 69 and 60% in the Gla‐300 and Gla‐100 groups (Table 1). Fourteen (3.5%) TEAEs in the Gla‐300 group and 15 (3.7%) in the Gla‐100 group were considered by the study investigator to be related to study medication. The most commonly reported TEAE was nasopharyngitis (Gla‐300, 12.2%; Gla‐100, 7.6%). Injection site reactions were experienced by 5 (1.2%) participants in the Gla‐300 group and 12 (3.0%) participants in the Gla‐100 group. Hypersensitivity reactions were reported by 19 participants (4.7%) in the Gla‐300 group and 20 participants (4.9%) in the Gla‐100 group.

Table 1.

Adverse events (safety population)

| n (%) | Gla‐300 (n = 403) | Gla‐100 (n = 406) |

|---|---|---|

| Participants with any TEAE | 278 (69.0) | 244 (60.1) |

| Participants with any treatment‐emergent SAE | 30 (7.4) | 30 (7.4) |

| Participants with any TEAE leading to death | 4 (1.0) | 2 (0.5) |

| Participants with TEAE leading to permanent treatment discontinuation | 11 (2.7) | 7 (1.7) |

| Any injection site reaction | 5 (1.2) | 12 (3.0) |

| Any hypersensitivity reaction | 19 (4.7) | 20 (4.9) |

TEAE, treatment‐emergent adverse event; SAE, serious adverse event.

The percentage of participants with treatment‐emergent serious AEs (SAEs) or TEAEs leading to treatment discontinuation during the 12‐month on‐treatment period were similar in the Gla‐300 and Gla‐100 groups (Table 1). Two (0.5%) SAEs in the Gla‐300 group (one case of hypoglycaemia and one acute myocardial infarction) and one (0.2%) in the Gla‐100 group (hypoglycaemia) were considered possibly related to study medication.

Four participants (1.0%) in the Gla‐300 group and 2 participants (0.5%) in the Gla‐100 group died owing to a TEAE. All those who died had pre‐existing, significant‐event‐related pathology and/or had multiple risk factors contributing to the fatal outcome. In the Gla‐300 group, three deaths (one from myocardial infarction, one from metastatic adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus and one from coronary artery disease) were not considered treatment‐related, and one death (attributable to acute myocardial infarction) was considered by the study investigator as possibly related to study medication or non‐study medication (specifically metformin). The two deaths in the Gla‐100 group (one myocardial infarction and one infection) were not considered related to study medication.

No differences were found between treatment groups in safety laboratory measurements, physical examination, vital signs or ECGs, or in numbers of participants reporting anti‐insulin antibodies, anti‐insulin antibodies titre or cross‐reactivity to human insulin.

Discussion

These 12‐month treatment results confirm the findings of the 6‐month initial study period 3. Equivalent glycaemic control was attained with both insulins, but less nocturnal confirmed [≤3.9 mmol/l (≤70 mg/dl)] or severe hypoglycaemia and less weight gain was observed with Gla‐300. The safety profiles of Gla‐300 and Gla‐100 were similar.

The reduction in HbA1c values observed in both treatment groups from baseline to month 6 3 was maintained at 12 months. When examining the mean eight‐point SMPG profiles, blood glucose was lower with Gla‐300 than with Gla‐100 between the pre‐dinner and bedtime time points. Better glycaemic control with Gla‐300 than with Gla‐100 at the end of a once‐daily evening dosing schedule might be explained by the longer duration of action of Gla‐300, which has been shown in PK/PD studies 1.

In addition to providing sustained glycaemic control, there was a 37% relative reduction in the annualized rate of nocturnal confirmed [≤3.9 mmol/l (70 mg/dl)] or severe hypoglycaemic events with Gla‐300 compared with Gla‐100, and a consistently lower proportion of participants experiencing at least one event. While it is necessary to use defined nocturnal and diurnal intervals of time for the purpose of analysis, these arbitrary definitions may not correspond to the daily habits of participants with regard to timing of sleep and the first meal of the day. As well as providing a significant reduction in hypoglycaemia during the predefined nocturnal (00:00–05:59 hours) period, a lower rate of hypoglycaemia compared with Gla‐100 was observed with Gla‐300 until the middle of the next day, in line with its PK/PD profile. In future studies and analyses, the actual timing of the overnight fasting interval should be considered when assessing the risk of hypoglycaemia. Severe hypoglycaemic events were uncommon in both treatment groups.

Lower nocturnal hypoglycaemia, with a small but significant improvement in HbA1c, was seen with Gla‐300 compared with Gla‐100 after 12 months of treatment in the EDITION 1 study, in which people with type 2 diabetes were treated with basal plus mealtime insulin 5. Similar glycaemic control with reduced nocturnal hypoglycaemia has been observed with insulin degludec 100 U/ml compared with Gla‐100 in people with type 2 diabetes treated with basal plus mealtime insulin 10, and in insulin‐naïve people 11. By contrast, another study in insulin‐naïve people with type 2 diabetes, using a more concentrated 200 U/ml formulation of insulin degludec, did not show a difference in nocturnal hypoglycaemia compared with Gla‐100 12; however, differences in study populations and definitions of hypoglycaemia limit direct comparisons of hypoglycaemia rates across all of these studies.

The mean daily doses of Gla‐300 and Gla‐100 remained relatively consistent throughout the 6‐month extension period of this study. A higher mean daily insulin dose of Gla‐300 was required, with the majority of dose titration occurring during the first 12 weeks of the study, as reported previously 3.

The cause of the difference in insulin dose is uncertain, but it may be attributable to greater inactivation of the glargine molecule by tissue proteases as a consequence of the longer residence time of Gla‐300 in the subcutaneous depot. A longer residence time is consistent with the extended absorption of Gla‐300, which results in the more prolonged PK/PD profile of action observed with Gla‐300 compared with Gla‐100 1, 13, 14.

Weight gain after 12 months of treatment remained low in both groups and was not felt to be of clinical concern. Furthermore, there was slightly, but statistically significantly, less weight gain with Gla‐300 than with Gla‐100. This was already apparent after 6 months 3. A trend for lower weight gain with Gla‐300 compared with Gla‐100 has also been observed in EDITION studies in other populations 4, 15, 16, 17. Further analyses are warranted to determine whether this difference can be explained by the difference in hypoglycaemia or other factors.

Occurrence of TEAEs, treatment discontinuation, injection site reactions and hypersensitivity reactions occurred with a similar pattern with Gla‐300 and Gla‐100. Both treatments were well tolerated and no safety concerns were identified at 12 months; longer‐term observation will be required to continue to monitor the safety profile of Gla‐300.

Limitations of the present study include its open‐label nature and a necessary reduction in ascertainment of hypoglycaemia and other events during the extension phase. The EDITION 2 study was restricted to the investigation of clinical outcomes of Gla‐300 treatment versus Gla‐100 in participants using a basal insulin and OAD (excluding sulphonylurea) regimen; however, the EDITION programme of clinical studies is investigating outcomes of Gla‐300 vs Gla‐100 treatment in other populations using different treatment regimens to cover the broader cross‐section of people with diabetes. Analyses of the 6‐month extension phases of EDITION 3 (insulin‐naïve participants), EDITION 4 (people with type 1 diabetes), EDITION JP 1 (Japanese people with type 1 diabetes) and EDITION JP 2 (Japanese people with type 2 diabetes using basal insulin plus OADs) are ongoing.

In summary, in a population using basal insulin plus OADs, excluding sulphonylurea, with a long duration of type 2 diabetes, high BMI, long‐term previous insulin use and high baseline HbA1c, findings from 12 months' treatment with Gla‐300 support and extend the EDITION 2 6‐month results. The sustained glycaemic control achieved in this challenging‐to‐treat population along with less nocturnal hypoglycaemia and weight gain compared with Gla‐100 is reassuring and suggests that these favourable results may be applicable to long‐term treatment in clinical practice.

Conflict of Interest

H. Y.‐J. has received honoraria for consulting and speaking from Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Merck (MSD) and Sanofi. R. M. B. has received research support and served as a consultant or on the scientific advisory board for Abbott Diabetes Care, Amylin, AstraZeneca/Bristol‐Myers Squibb Alliance, Bayer, Becton Dickinson, Boehringer Ingelheim, Calibra, DexCom, Eli Lilly, Halozyme, Hygieia, Johnson & Johnson, Medtronic, Merck (MSD), Novo Nordisk, Roche, Sanofi and Takeda, is employed by non‐profit Park Nicollet Institute, who contract for his services and pay him no personal income, has inherited Merck (MSD) stock, and has been a volunteer for the American Diabetes Association and Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF). G. B. B. has received honoraria for advising and lecturing from Eli Lilly, Novartis and Sanofi. M. Z., M. W. and I. M.‐B. are employees of Sanofi. M. M. is an employee of Umanis. M. C. R. has received research grant support from Amylin, Eli Lilly and Sanofi, and honoraria for consulting and/or speaking from Amylin, AstraZeneca/Bristol‐Myers Squibb Alliance, Elcelyx, Eli Lilly, Sanofi and Valeritas. These dualities of interest have been reviewed and managed by Oregon Health and Science University.

H. Y.‐J. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Sanofi was the sponsor of the study, and was responsible for the design and coordination of the trial. Sanofi monitored the clinical sites, collected and managed the data, and performed all statistical analyses. H. Y.‐J., R. M. B., G. B. B. and M. C. R. participated in the design of the study programme and protocol, analysis and interpretation of the data and in the writing, reviewing and editing of the manuscript. M. Z. and I. M.‐B. contributed to the design and treatment considerations for the trial, analysed and interpreted the data, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. M. W. and M. M. analysed and interpreted the data, and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Supporting information

Table S1. Hypoglycaemia over 12 months in the EDITION 2 study (safety population).

Figure S1. (A) Glycated haemoglobin mean change from baseline by visit. (B) Fasting plasma glucose mean change from baseline by visit. (C) Eight‐point self‐monitored plasma glucose profile mean change from baseline at 12 months (modified intention‐to‐treat population).

Figure S2. Mean change in body weight over the 12‐month study period (safety population).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Sanofi. The authors thank the study participants, trial staff and investigators for their participation. The authors would also like to thank Cassandra Pessina (Sanofi) for critical review of the manuscript, and for assistance with management of the manuscript development. Editorial assistance was provided by Julianna Solomons of Fishawack Communications and was funded by Sanofi.

References

- 1. Becker RH, Dahmen R, Bergmann K, Lehmann A, Jax T, Heise T. New insulin glargine 300 units.mL‐1 provides a more even activity profile and prolonged glycemic control at steady state compared with insulin glargine 100 units.mL‐1 . Diabetes Care 2015; 38: 637–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kunt T, Snoek FJ. Barriers to insulin initiation and intensification and how to overcome them. Int J Clin Pract 2009; 63 (Suppl. 164): 6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yki‐Järvinen H, Bergenstal R, Ziemen M et al. New insulin glargine 300 U/mL versus glargine 100 U/mL in people with type 2 diabetes using oral agents and basal insulin: glucose control and hypoglycaemia in a 6‐month randomised controlled trial (EDITION 2). Diabetes Care 2014; 37: 3235–3243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bolli G, Riddle M, Bergenstal R et al. New insulin glargine 300 U/mL versus glargine 100 U/mL in insulin naïve people with type 2 diabetes using anithyperglycemic drugs: glucose control and hypoglycemia in a randomized controlled trial (EDITION 3). Diabetes Obes Metab 2015; 17: 386–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Riddle MC, Bolli GB, Ziemen M, Muehlen‐Bartmer I, Bizet F, Home PD. New insulin glargine 300 units/mL versus glargine 100 units/mL in people with type 2 diabetes using basal and mealtime insulin: glucose control and hypoglycemia in a 6‐month randomized controlled trial (EDITION 1). Diabetes Care 2014; 37: 2755–2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E et al. National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med 2003; 139: 137–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. American Diabetes Association . Defining and reporting hypoglycemia in diabetes: a report from the American Diabetes Association Workgroup on Hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care 2005; 28: 1245–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bradley C, Lewis KS. Measures of psychological well‐being and treatment satisfaction developed from the responses of people with tablet‐treated diabetes. Diabet Med 1990; 7: 445–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lewis KS, Bradley C, Knight G, Boulton AJ, Ward JD. A measure of treatment satisfaction designed specifically for people with insulin‐dependent diabetes. Diabet Med 1988; 5: 235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Garber AJ, King AB, Del Prato S et al. Insulin degludec, an ultra‐longacting basal insulin, versus insulin glargine in basal‐bolus treatment with mealtime insulin aspart in type 2 diabetes (BEGIN Basal‐Bolus Type 2): a phase 3, randomised, open‐label, treat‐to‐_target non‐inferiority trial. Lancet 2012; 379: 1498–1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zinman B, Philis‐Tsimikas A, Cariou B et al. Insulin degludec versus insulin glargine in insulin‐naive patients with type 2 diabetes: a 1‐year, randomized, treat‐to‐_target trial (BEGIN Once Long). Diabetes Care 2012; 35: 2464–2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gough SC, Bhargava A, Jain R, Mersebach H, Rasmussen S, Bergenstal RM. Low‐volume insulin degludec 200 units/ml once daily improves glycemic control similarly to insulin glargine with a low risk of hypoglycemia in insulin‐naive patients with type 2 diabetes: a 26‐week, randomized, controlled, multinational, treat‐to‐_target trial: the BEGIN LOW VOLUME trial. Diabetes Care 2013; 36: 2536–2542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Riddle MC, Yki‐Järvinen H, Bolli GB et al. One‐year sustained glycaemic control and less hypoglycaemia with new insulin glargine 300 U/ml compared with 100 U/ml in people with type 2 diabetes using basal plus meal‐time insulin: the EDITION 1 12‐month randomized trial, including 6‐month extension. Diabetes Obes Metab 2015; 17: 835–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ritzel R, Roussel R, Bolli GB et al. Patient‐level meta‐analysis of EDITION 1, 2 and 3: glycaemic control and hypoglycaemia with new insulin glargine 300 U/mL versus glargine 100 U/mL in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2015; 17: 859–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Matsuhisa M, Koyama M, Cheng XN, Shimizu S, Hirose T, on behalf of the EDITION JP 1 study group . New insulin glargine 300 U/mL: glycemic control and hypoglycemia in Japanese people with T1DM (EDITION JP 1). Diabetes 2014; 63(Suppl. 1A): LB22. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Home P, Bergenstal R, Riddle MC et al. Glycemic control and hypoglycemia with new insulin glargine 300 U/mL in people with T1DM (EDITION 4). Diabetes 2014; 63(Suppl. 1A): LB19. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Terauchi Y, Koyama M, Cheng XN, Shimizu S, Hirose T. Glycemic control and hypoglycemia in Japanese people with T2DM receiving new insulin glargin 300 U/mL in combination with OADs (EDITION JP 2). Diabetes 2014; 63: LB24. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Hypoglycaemia over 12 months in the EDITION 2 study (safety population).

Figure S1. (A) Glycated haemoglobin mean change from baseline by visit. (B) Fasting plasma glucose mean change from baseline by visit. (C) Eight‐point self‐monitored plasma glucose profile mean change from baseline at 12 months (modified intention‐to‐treat population).

Figure S2. Mean change in body weight over the 12‐month study period (safety population).