Newsom aims to limit unhealthy food in California, getting ahead of Trump administration and RFK Jr.

- The move builds on California’s work to ban several food additives commonly found in popular cereal, soft drinks and candy and to block schools from providing Flamin’ Hot Cheetos and other snacks made with certain synthetic dyes.

- The order comes as President-elect Donald Trump seeks Senate confirmation of Robert F. Kennedy Jr. as his nominee for Secretary of Health and Human Services.

- Kennedy, a controversial anti-vaccine activist and a vocal critic of ultra-processed foods, promised to radically overhaul the country’s food system.

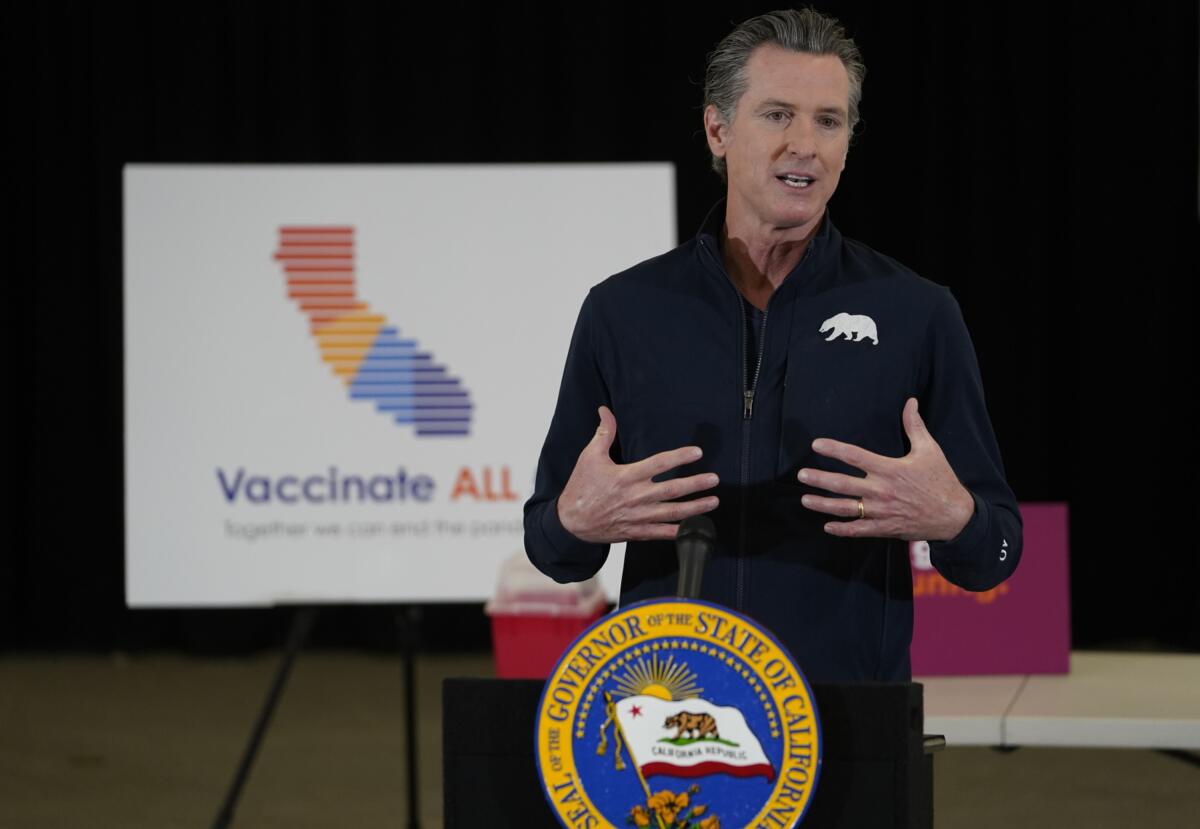

Gov. Gavin Newsom issued an executive order on Friday attempting to limit access to ultra-processed foods, a directive he cast as a continuation of California’s “nation leading” nutrition and health standards.

“The food we eat shouldn’t make us sick with disease or lead to lifelong consequences,” Newsom said in a statement. “California has been a leader for years in creating healthy and delicious school meals, and removing harmful ingredients and chemicals from food. We’re going to work with the industry, consumers and experts to crack down on ultra-processed foods and create a healthier future for every Californian.”

The order directs state agencies to develop recommendations to limit the health harms of ultra-processed foods and calls for proposals to reduce the purchase of candy, soda and other unhealthy foods made with synthetic dyes or additives by recipients of government food benefits.

The move comes weeks before President-elect Donald Trump is sworn into office for his second term, with iconoclastic former environmental lawyer Robert F. Kennedy Jr. as his nominee for secretary of Health and Human Services. Kennedy still needs to be confirmed by the Senate, but he has been a vocal critic of ultra-processed foods and promised to radically overhaul the country’s food system. Food dyes, pasteurized milk and seed oils are among the common items he has criticized, sometimes making health claims that are not backed up by science.

Though Newsom didn’t mention Kennedy, the Democratic governor of California is planting a preemptive flag around the issue and signaling his refusal to concede the terrain to the incoming Trump administration. His executive order included a long list of steps the state has taken to improve nutrition.

Processed foods are foods altered from their natural form, like frozen vegetables, whereas ultra — or highly —processed foods are foods that have been significantly altered from their natural state, like packaged chips or soft drinks. Ultra-processed foods make up the vast majority of the U.S. food supply, research shows.

More to Read

“Part of why people want change in the food system is because the regulatory system has been very lax,” said Charlotte Biltekoff, who researches the cultural politics of food and health and serves as the Corti Endowed Professor in Food, Wine and Culture at UC Davis.

The U.S. regulatory framework is much more lenient than the framework in Europe, where many additives are banned that are still allowed in the U.S.

“This is actually a contest between different kinds of authority: Who gets to decide, and based on what kind of knowledge, what good food is,” Biltekoff said, suggesting that Newsom’s order would likely receive blowback from the food industry.

In years past, the soda lobby has killed proposals in Sacramento to put health warnings on sugary beverages, and associations representing candy makers, snack food companies and convenience stores have lobbied against efforts to limit dyes and additives. They’ve argued that food safety is sufficiently regulated and that making a patchwork of rules in different states is untenable for business.

The Golden State has been a national leader in banning food additives, with Newsom signing a 2023 bill that made California the first state in the nation to prohibit four additives found in popular cereal, soda, candy and drinks.

The California Food Safety Act was colloquially referred to as the “Skittles ban” before its passage because an earlier version of the bill also _targeted titanium dioxide, which is used to color Skittles and several other popular candies. But the final law was amended to remove reference to the substance, solely banning brominated vegetable oil, potassium bromate, propylparaben and red dye No. 3.

The anti-vaccine activist could oversee the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Food and Drug Administration and the National Institutes of Health.

Last year, Newsom signed a separate bill into law that bars snack foods containing a number of synthetic food dyes from California public schools. That law will prevent popular snack foods like Flamin’ Hot Cheetos from being stocked in school vending machines or cafeterias when it goes into effect on Dec. 31, 2027.

Laws to protect students from sugary drinks go back decades: In 2009 California banned all K-12 schools from offering soda.

The governor’s order cites the link between “ultra-processed foods” and cancer, obesity, diabetes and other health problems. The order says the U.S. allows more than 10,000 chemicals in food, color additives or ingredients, compared to 300 that are allowed in the European Union.

Newsom is requiring the California Department of Public Health to provide recommendations by April 1 to limit the harms associated with ultra-processed foods and food ingredients that pose a health risk, which may include warning labels. He tasked the Californa Department of Social Services to issue recommendations to reduce the purchase by California food-stamp users of soda, candy other ultra-processed foods, or foods made with synthetic food dye or additives on the same timeline.

Among several health directives, his order also requires state agencies to identify areas to increase standards for healthy school meals and to investigate the negative health consequences of food dyes.

For the fifth time in as many years, a proposal to require health warning labels on sugary drinks in California was scuttled Tuesday in the Legislature, putting an end to a package of measures aimed at reducing obesity by regulating sodas.

Ultra-processed foods will likely be at the forefront of the national discourse in the coming weeks as Kennedy prepares for his Senate confirmation hearing.

Kennedy, a prominent anti-vaccine activist, has promoted a number of false health claims and fringe conspiracy theories. But his positions against food additives have also brought support from unlikely bedfellows who have criticized other parts of his “Make America Healthy Again” agenda.

“Yes, there are some things that he supports that we would agree with, but they feel more like the stopped clock that’s right twice a day,” Dr. Peter Lurie, president and executive director of the Center for Science in the Public Interest, said in an earlier interview with The Times — citing food additives as one example.

Lurie characterized Kennedy’s potential appointment more broadly as a dangerous choice because of his inability “to discern the difference between good and bad science.”

The Food and Drug Administration — the agency perhaps most publicly in Kennedy’s crosshairs — could be significantly impacted by his leadership if he is confirmed by the Senate.

The agency, which falls under the the Department of Health and Human Services, has a massive purview, regulating about 77% of the U.S. food supply and overseeing the safety of nearly $4 trillion worth of food, tobacco and medical products, according to federal data.

Kennedy has said he would clear out “entire departments” at FDA, such as those overseeing nutrition, arguing that the agency hasn’t been “protecting our kids.” Kennedy has called for banning ultra-processed foods from school lunches and criticized the impacts of food dyes. He has also made some assertions about the food supply that experts say are incorrect, such as alleging that Americans are “being unknowingly poisoned” by seed oils.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.