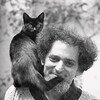

Walter Abish (1931–2022)

Author of How German Is It

About the Author

Walter Abish was born in Vienna, Austria. Much of his childhood was spent in China. He became an American citizen in 1960. Abish's fascination with human communication led him to write works focused on the use of language. His first novel, Alphabetical Africa (1974), was an experiment in show more alliteration, moving forward and backward through the alphabet while telling the story. Throughout the 1970s, he wrote short stories that demonstrated a variety of unique writing formats. His second novel, How German Is It (1980), a more conventionally written book, received the 1981 PEN/Faulkner award, an honor bestowed by his peers. In Eclipse Fever (1993), Abish continues to play with language, this time within the context of a suspense story about Mexico's social and intellectual elite. Abish lives in New York where he is a lecturer in English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University. (Bowker Author Biography) show less

Image credit: Joyce Ravid

Works by Walter Abish

Renegade #1 1 copy

Associated Works

Antaeus No. 64/65, Spring/Autumn 1990 - Twentieth Anniversary Issue (1990) — Contributor — 12 copies

Personal Injury Magazine, no. 4 — Contributor — 1 copy

Tagged

Common Knowledge

- Canonical name

- Abish, Walter

- Birthdate

- 1931-12-24

- Date of death

- 2022-05-28

- Gender

- male

- Nationality

- Austria

USA - Birthplace

- Vienna, Austria

- Place of death

- New York, New York, USA

- Places of residence

- Vienna, Austria

Nice, France

Shanghai, China

Israel

New York, New York, USA - Occupations

- author

lecturer

Holocaust survivor

novelist

short story writer

librarian (show all 7)

memoirist - Organizations

- International PEN

- Awards and honors

- Guggenheim Fellowship

MacArthur Fellowship (1987)

American Academy of Arts and Sciences (fellow, 1998) - Short biography

- Walter Abish was born to a prosperous Jewish family in Vienna, Austria. His parents were Friedl and Adolph Abish, a perfumer. After Nazi Germany's Anschluss (annexation) of Austria, they fled the country, traveling first to Nice, France, before taking a ship to Shanghai, China. They lived there in a Jewish ghetto from 1940 to 1948. In 1948, they moved to Israel, where Abish served in the army and then worked in the American Library. In 1957, the family emigrated to the USA. He was in his 40s when he published his debut novel, Alphabetical Africa, in 1974. It was the first of his experimental fiction works, and was quickly followed by his first collection of short stories, Minds Meet (1975). His second novel, How German Is It?/Wie Deutsch ist es? (1980), is his most celebrated work and won the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction in 1981. Abish received a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1979, a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1981, and a MacArthur Fellowship in 1987. In his career, Abish published three novels, three collections of short stories, a volume of poems, and a memoir, Double Vision (2004). He also worked and taught at Empire State College, Wheaton College, the University at Buffalo, The State University of New York, Columbia University, Brown University, Yale University, and Cooper Union. He sat on the contributing editorial board of the literary journal Conjunctions, and served on the board of International PEN from 1982 to 1988. He was on the Board of Governors for the New York Foundation for the Arts. Abish was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1998. He married Cecile Gelb, a photographer and sculptor, in Tel Aviv in 1953.

Members

Reviews

Lists

Best First Lines (1)

Gimmicks (1)

Awards

You May Also Like

Associated Authors

Statistics

- Works

- 12

- Also by

- 11

- Members

- 1,019

- Popularity

- #25,282

- Rating

- 3.6

- Reviews

- 13

- ISBNs

- 38

- Languages

- 6

- Favorited

- 8

Where I struggled with the novel and wasn't completely satisfied was with the characters and the plot. Many of the characters are left partially developed. Perhaps this is intentional. Perhaps this is how some of the German citizens today feel. The plot never really happened. It went off in several different directions, all of which were interesting, but none of which was really seen through to the end, except one that felt too minimally developed. This was almost an incredible reading experience, but it was a very enjoyable one and very enlightening as well; it helped me look at the issues in new and different ways.

… (more)