Click on a thumbnail to go to Google Books.

|

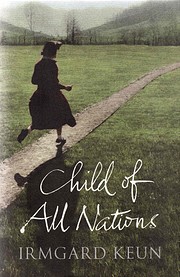

Loading... Child of All Nations (original 1938; edition 2008)by Irmgard KeunChild's eye view of pre-war Europe By sally tarbox on 23 April 2014 Format: Kindle Edition It's the lead-up to World War II; 10 year old Kully, the narrator, is excluded from her native Germany as her writer father has produced work critical of the Nazi regime. She recounts her experiences as she travels round Europe with her parents. As translator Michael Hoffmann observes in his afterword, their life was 'a lavish existence of hotels and restaurants and first-class travel that kept one imprisoned in a sort of luxurious but penurious bubble. One couldn't afford to break the illusion, say, by making economies because that would destroy one's credit.' Thus Kully recounts meals in grand hotels where she is left behind after as security while her father - urbane, charming, womanizing - goes off to pawn her coat to pay the bill. Life is a constant struggle to squeeze money out of publishers and friends, and Kully is old before her time, an onlooker in a world where champagne and sophistication rub shoulders with hunger and fake passports. Kully's father is only shown once to drop his worldly and selfish 'front' - on returning to his family under an assumed name, and immediately after sweet-talking his landlady into allowing his wife in, the true stresses of war become apparent: 'All of a sudden my father looks terribly pale and tired. He sits my mother down on the bed, and then he falls down. His head is on her knees. My mother lays both her hands on his hair.' I felt the story was weakened by the last section where Kully spends some time in USA with her father. Somehow it detracted from the terrible situation they would undergo in Europe. But nonetheless an excellent read. Child of All Nations by Irmgard Keun Unable to publish, with her books banned, Irmgard Keun joined the German literary diaspora in Europe. From June 1936 until January 1938 she travelled with Joseph Roth. They borrowed from acquaintances, extracted advances from publishers, and lived on credit, moving on when their visas expired. Kully, the nine-year old narrator of [Child of All Nations] travels the same route as Keun and Roth. The character of her unreliable, extravagant father may even be based on Roth. The book begins with Kully and her mother, Annie, stranded penniless in a first-class hotel in Ostende while Kully's father tries to raise money in Prague. Annie and Kully avoid the front desk and eat only one meal a day in the restaurant, where they order the most expensive dishes on the menu because they are afraid of annoying the waiters. Under instructions from her husband, Peter, Annie desperately tries to wangle an advance from Peter's Belgian publisher so that she can pay the hotel bill and move on to Amsterdam. The unpaid bills, the expired visas, Peter’s absences and her mother’s sadness are the norm for Kully. She knows that her father cannot return to Germany because he would be jailed. She cannot write to her friends in Germany because receiving a letter could put them at risk from the Nazis. She hears her parents and their friends talk of death, and witnesses the attempted suicide of another writer. Kully relates these events from the matter-of-fact, accepting perspective of a nine-year-old. Keun’s book provides a fascinating glimpse of life as an exile from Hitler’s Germany. Highly recommended. |

Current DiscussionsNonePopular covers

Google Books — Loading... Google Books — Loading...GenresMelvil Decimal System (DDC)833.912Literature German & related literatures German fiction 1900- 1900-1990 1900-1945LC ClassificationRatingAverage: (3.8) (3.8)

Is this you?Become a LibraryThing Author. |

By sally tarbox on 23 April 2014

Format: Kindle Edition

It's the lead-up to World War II; 10 year old Kully, the narrator, is excluded from her native Germany as her writer father has produced work critical of the Nazi regime.

She recounts her experiences as she travels round Europe with her parents. As translator Michael Hoffmann observes in his afterword, their life was 'a lavish existence of hotels and restaurants and first-class travel that kept one imprisoned in a sort of luxurious but penurious bubble. One couldn't afford to break the illusion, say, by making economies because that would destroy one's credit.'

Thus Kully recounts meals in grand hotels where she is left behind after as security while her father - urbane, charming, womanizing - goes off to pawn her coat to pay the bill. Life is a constant struggle to squeeze money out of publishers and friends, and Kully is old before her time, an onlooker in a world where champagne and sophistication rub shoulders with hunger and fake passports. Kully's father is only shown once to drop his worldly and selfish 'front' - on returning to his family under an assumed name, and immediately after sweet-talking his landlady into allowing his wife in, the true stresses of war become apparent:

'All of a sudden my father looks terribly pale and tired. He sits my mother down on the bed, and then he falls down. His head is on her knees. My mother lays both her hands on his hair.'

I felt the story was weakened by the last section where Kully spends some time in USA with her father. Somehow it detracted from the terrible situation they would undergo in Europe. But nonetheless an excellent read. (