Click on a thumbnail to go to Google Books.

|

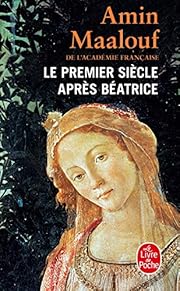

Loading... Le Premier Siecle Apres Beatrice (edition 1994)by Maalouf AminScience fiction of a sort but, in the end, a little too didactic or philosophical for me. Maybe it just wasn’t a good book. I opened it with great anticipation; I read Leo Africanus many years ago and was quite impressed. But I had never gotten back to Maalouf until now. The plot, such as it is, relates to real and artificial limitations on the female birth rate and the catastrophic implications for civilization. Maalouf has certainly done his research and the book is almost frighteningly plausible. Sadly, the longer it goes on, the less impressive it is. The allegory about inequality, racism, and related matters becomes less powerful the more Maalouf flogs it. He doesn’t know when to let up and, sadly, his characters are more vehicles for points of view than they are fully developed people with whom the reader can connect. Well written but ultimately unsatisfying short novel about a near future in which the Middle East sees a steep population decline in its women. Only preferred baby boys are born in patriarchal countries. It's a fascinating premise and could have lived up to that if it really went into the social effects of this change, but it doesn't do that. It doesn't look for a second at the social changes in partriarchal societies and how women are affected. It's all whining about how it has affected him and other poor, innocent men who can't get wives! What will they do?!?! Maalouf comes off as a misogynist because this book about women entirely erases the experiences of women under this regime. Not an effective book. The First Century after Beatrice is an important book. It depicts a future in which unscrupulous scientists create a "cure" for daughters, when a man can take a pill to guarantee that he will only father sons. Combined with archaic cultures where a man is nothing without sons, the results prove catastrophic, and the whole world feels the effects. We experience this brave new world, the "Century after Beatrice", through the eyes of a French entomologist, who first encounters the pills in Cairo, where he is attending an academic conference on scarabs. Unlike the men who take them, his greatest desire is to have a daughter, who will be named Beatrice. His partner Clerence, a beautiful journalist, makes the fight against it her life's mission. When she faces opposition at her workplace, she takes maternity leave and gives her husband the daughter he's always wanted. He's the nurturing one, and she's the careerist, but they make a great team. With the aid of two Holocaust survivors, who quickly grasp the consequences of what is going on, they establish a society to agitate against it. However, the majority of the industrialized world either doesn't think the pills are a big deal, or, more insidiously, think that the subsequent population shrinkage in the global south is a good thing. Until the obvious results of too many men with no hope for a family and no outlet except violence erupt and send refugees streaming northward and women and girls being trafficked southward. While there are no magic beans to cure men from the curse of daughters, sex selective abortion and infanticide are big issues with global consequences that are very, very real in today's society. Only time will tell what the end result will be in places like China and India where thousands of girls are not born every year. As realistically as the events in Beatrice unfold, I can only hope for a different fate for our world than theirs. Originally published in French in 1992, The First Century after Beatrice is in many ways a prescient book, although the cultural references to events like Watts and Sarajevo may not resonate as strongly as when it was written. However, it is the epitome of what good speculative fiction should be: exploring current issues to their furthest ends and provoking thought as well as providing entertainment. Not just about gender equality, Maalouf's book also addresses concerns like racism, colonialism, and Western support for third-world dictators. Unfortunately it's no longer in print in the States, but the UK paperback edition can be ordered from BookDepository. I highly, highly recommend it. This is one of the most beautiful modern novels I have read. Its only flaw is that it's a short book, I have reread it because it leaves me wanting more. I think it's also my favorite work of speculative fiction. The speculation involves the creation and promotion of a drug that prevents women from having girl children. The long term result is economic collapse, and an increase in male violence. The protagonist is a shy entomologist, whose partner and the love of his life is a journalist much bolder than himself, always traveling for her work and campaigning against the drug. He has mostly raised their adored daughter, Beatrice. The prose is very fine, lovely and eloquent, and what could be a very didactic novel is a pleasure, a page-turner, and an inspiring mediation on human nature, sexism, and science. What if you could guarantee the birth of a boy? Would you? Some of the best science fiction starts out with a simple premise, like the desire to have sons, and spins it out to its disastrous end. Throughout history, throughout most of the world, sons have been desired over daughters. This is still the case in much of the modern world and has been the theme of many novels. Science fiction makes it possible to look at the consequences of getting our collective wish, of being able to guarantee the birth of sons. Amin Maalouf's novel, The First Century After Beatrice centers on a French entomologist who finds a curious kind of bean in a Cairo market while attending a symposium on scarab beetles. Swallow the bean, and your children will all be boys. The entomologist wants nothing more than to marry his love Clarence and for her to give him a daughter, so he has no interest in the bean. However, while on assignment in India for the Parisian newspaper she works for, Clarence discovers a local clinic that has seen the birth rate of girls drop to nothing. She begins to connect the dots and discovers that the properties of the bean have been mass produced and marketed to growing numbers of communities where sons are still greatly preferred over daughters. She explains the problem Europe will eventually face. Most people in Europe don't care one way or another what sex their child is. Those who do care are evenly split between wanting boys and wanting girls. Those who don't care will continue to have both sons and daughters as will those who want daughters. Those who want sons, however, can take a pill that will guarantee the birth of a boy. This means that the next generation, instead of being close to 50-50 male to female, will be 68-32 male to female. Be careful what you wish for. The First Century After Beatrice is a warning, a parable much like P.D. James's book The Children of Men. I suspect the medical technology necessary to pre-determine the sex of a child is probably not all that far in our futures. Should it become available to the entire population before we all reach a point where neither sex is favored the results could certainly be disastrous. In this sense, The First Century After Beatrice is a useful warning. But The First Century After Beatrice is also a love story. The entomologist narrator is in love with his wife and devoted to his daughter Beatrice. For the first 50 pages or so of the novel I thought I was reading a romance. A darn good one, too. I may have an issue with the translation. It's very difficult for me to judge the writing when reading something in translation. Is what I find problematic the result of the translator's lack of ability, or is the translator simply doing her job, conveying both the content and the style of the original? I found the narrator's English to be awkward. He is a professor, a scientist, an entomologist who sometimes speaks in ways that don't ring altogether natural. He narrates as though he is performing the story, delivering it as a lecture instead of just telling it in a natural voice. This could be Mr. Maalouf showing us an aspect of his narrator's character. That's how I'm choosing to view it. Maybe you'll see what I mean in this wonderful passage describing his godfather's library. I remember, as a matter of fact, that at the end of my very first visit, he walked over to his bookcase at the other end of the sitting-room. All the volumes were in antique leather bindings and from a distance all looked alike. He took one down and gave it to me. Gulliver's Travels. I could keep it. I was nine years old, and I don't remember whether on my next visit I noticed that there was still a gap where the book had been. Only, over the course of the years, the bookcase was studded with similar gaps until it resembled a toothless mouth. Not once did we remark on this, but I eventually realized that these places would remain empty; that for him they were now as sacred as the books; and that these phantom volumes, carved out of the buff-coloured leather, represented all men's unspoken love and the pride they took in plundering their own collections. See what I mean? Not once did we remark on this. This does not sound like natural language to me at all, but the image is so wonderful that I'm willing to excuse the faults I find in it. I feel the same way about the book itself This is a wonderful novel narrated by a scientist about love, tolerance and humanity. A mysterious 'substance' appears to contain the answers to the problems of the world; its use results in a situation reminiscent of an end of days scenario that still looms large over the novel at its closure. This is a very thoughtful and sensitive read;. The translation into English captures the tone and balance of the original text in all but the smallest cultural details, unavoidably lessened through their transmittance into another set of linguistic cultual codes. Que se passerait-il si on pouvait choisir le sexe des bébés à naître? Maalouf explore cette possibilité, comme une catastrophe, dans des sociétés qui privilégient le garçon et qui élimineraient les filles, jusqu'à se retrouver avec un grand déficit de femmes et beaucoup de violence. L'idée n'est pas mauvaise, mais Maalouf fait du Maalouf, ou bien c'est moi qui ai assez lu cet auteur et qui me lasse... Another of the three novels by the Lebanese-French master storyteller which I bought in an underground bookshop while on honeymoon with my dear wife Dawn in Agadir Maroc in 2001, this is also translated by Dorothy S. Blair, as was 'the Gardens of Light,' also published in the same series by Abacus, printed by Clays Ltd., St. Ives, England and translated from the original French publication by Editions Bernard Grasset. It has a price of 125.00 dirhams penciled inside on the first page upper right. |

Current DiscussionsNonePopular covers

Google Books — Loading... Google Books — Loading...GenresMelvil Decimal System (DDC)843Literature French & related literatures French fictionLC ClassificationRatingAverage: (3.57) (3.57)

Is this you?Become a LibraryThing Author. |