Click on a thumbnail to go to Google Books.

|

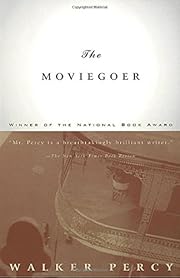

Loading... The Moviegoer (original 1961; edition 1998)by Walker Percy (Author)at first i was really liking this, the way that we see binx being lost in his life but finding his way through cinema but then it turned into something else and i myself was the one lost. i disliked the depiction of just about everyone (women, people of color) that he encountered and don't know if this is just another of the older books written by white men that i don't find any connection with, or if there was really just nothing to connect to. this won the national book award in 1960 (and was percy's first book), and i'm disappointed not to like it more. this description is so spot on though: "...I have only to hear the word God and a curtain comes down in my head." This is a singular book. Written in a laconic style that has the pacing of noir and the worldview of a Camus character but yet, infused with an easygoing sense of the speed of life in the suburbs of Louisiana . I liked all the descriptions of character and place. People aren't happy and that's a lot of what this is. People who are looking for a plot-driven story, please choose a different novel. Some have referred to this book as the first modern novel. Like a heaping plate of comfort food for me. Also contains one of my favorite quotes in a novel: “Whenever I feel bad, I go to the library and read controversial periodicals.” Hell yeah. But wait, there’s more. Binx Bolling doesn’t seem to be having a bad time of it, a young man successfully managing an office of the family brokerage firm in 1959/1960 New Orleans, having a series of dalliances with his secretaries, and going to a lot of movies. Only unlike most of us, he has the knowledge that such things are merely an effort to keep the existential despair at bay at the forefront of his mind. He instinctually feels the quote from Kierkegaard that is the novel’s epigraph: “the specific character of despair is precisely this: it is unaware of being despair”. Now he knows he is in despair and thus he is a bit better off by Kierkegaard’s reckoning, a step closer to the solution to it, but he is still a long way off a grounding of himself in religious faith. The forms and husk of religion are all around him of course, being plenty thick in the “Christ-haunted” but not “Christ-centered” South, as Flannery O’Connor memorably phrased it, but Kierkegaard too would have recognized the deadness of them. The best Binx can do is an awareness of “wonder” and a rejection of that which he feels too grossly ignores or obscures the wonder. His state of despair and inadequate search for resolution to it are best recognized for what they are by his step-cousin Kate, who is often in the grip of a strong depression, who seems possibly bipolar. Like recognizes like, in a manner. She tells him, “You remind me of a prisoner in the death house who takes a wry pleasure in doing things like registering to vote. Come to think of it, all your gaiety and good spirits have the same death house quality. No thanks. I’ve had enough of your death house pranks”. She tells him, “It is possible, you know, that you are overlooking something, the most obvious thing of all. And you would not know it if you fell over it.” Not that she knows what it is either, rather she’s given up the possible search: “Don’t you worry. I’m not going to swallow all the pills at once. Losing hope is not so bad. There’s something worse: losing hope and hiding it from yourself.” Binx, like Kate and Kierkegaard, understands the commonplace human tendency to hide our despair from ourselves, what he calls “sinking into everydayness”, even if the three of them (in the novel’s current moment at least) exist in pretty different places after similarly escaping it. Kierkegaard thinks he knows the answer. Kate thinks there is no answer. Binx, as befits a more modern day literary fiction hero, embraces uncertainty. Watching an apparently materially successful African-American man exiting church on Ash Wednesday, the ending day of the novel, ashes marked on forehead, he thinks I watch him closely in the rear-view mirror. It is impossible to say why he is here. Is it part and parcel of the complex business of coming up in the world? Or is it because he believes that God himself is present here at the corner of Elysian Fields and Bons Enfants? Or is he here for both reasons: through some dim dazzling trick of grace, coming for the one and receiving the other as God’s own importunate bonus? It is impossible to say. This short book was actually a very long book about a loser misogynist 30 year old who does absolutely nothing and complains about it constantly. (Ok, so it's something between a coming of age novel and a mid-life crisis novel about a wealthy-class New Orleans man who is unhappy and wants more from life. He goes on various mild escapades with several women but there's no real plot whatsoever.) That said, the writing is fantastic: very atmospheric and perfectly capturing New Orleans and also Chicago. The writer is also very observant and astutely describes several phenomenon that make the novel almost worth reading. Hart to believe this won the National Book Award, but maybe it just hasn't aged well? It’s hard to get terribly excited about a book where the main character, John Bickerson “Binx” Bolling, talks about malaise throughout the book. Binx is 29 and lives in a basement apartment in Gentilly, a suburb of New Orleans. His main activities are working as a stockbroker, going to the movies, and pursuing his secretaries for sex. The writing is strong, but the book follows a character who can only be briefly satisfied, then sinks back into a morass of malaise. He is constantly searching for meaning in life, but not finding much of anything. His great-aunt Emily tries to steer him in a positive direction, while her stepdaughter, Kate, contemplates suicide. Here’s an example of Binx’s inner dialogue: “What is malaise? you ask. The malaise is the pain of loss. The world is lost to you, the world and the people in it, and there remains only you and the world and you no more able to be in the world than Banquo’s ghost.” What I liked: - The writing is eloquent - The sense of place is vivid – it is easy to picture New Orleans in 1954 - Emily’s speech near the end says what I have been thinking throughout the book What I disliked: - It is very difficult to feel much empathy for Binx due to his self-centeredness, racism, sexism, and lack of appreciation for his privileged life - There is little to no plot – I typically enjoy character-driven novels, but I need at least a tiny bit of storyline to hold everything together - There is no natural flow to the story – it feels like a disjointed series of memories and musings This book won the National (US) Book Award for Fiction in 1962. If you like philosophical stories about existential angst, you may like it more than I did. It is well-written but rather dreary. Binx Bolling is a man in search of meaning. His life doesn’t seem to have much meaning; he goes to movies and engages in sex with a string of vacuous young women who occupy the front office secretarial position in his office. He doesn’t seem to belong to anything or anyone, but then we find he has a family and that his life is not unentangled, it is possibly too deeply entangled. There is no shortage of persons to tell him who he is, or at least who he ought to be, only a shortage of people who actually know who he is or want to see him for himself. But then, there is his cousin (not really because his aunt is only her stepmother), Kate, and Kate, like him, is a searcher who cannot find her way. I loved the way this story developed, particularly the psychological unveiling of the characters as the plot unfolds. Binx has reasons for his state of confusion, he has survived the trauma of the Korean War and he has failed to pick up his life and sink back into the oblivion of the everyday. Kate, likewise, has endured a traumatic event and been left running from the loss of her planned future and the pointlessness of the life that has been spared to her. Aunt Emily is their foil: she is sure she knows what life is about and that she has all the answers, and she seems unable to grasp why these kids don’t just follow instructions and join the dance in-step. Percy has woven very believable characters into a very realistic world. It is a world of class distinction, pre-determined futures, and family expectations. And, his South seems very real as well. That he understands his subject is obvious. He captures the world of New Orleans and the pressures of a Southern identity. Nobody but a Southerner knows the wrenching rinsing sadness of the cities of the North. Knowing all about genie-souls and living in haunted places like Shiloh and the Wilderness and Vicksburg and Atlanta where the ghosts of heroes walk abroad by day and are more real than people, he knows a ghost when he sees one, and no sooner does he stop off the train in New York or Chicago or San Francisco than he feels the genie-soul perched on his shoulder. Percy won the National Book Award for this, his first, novel, and I can see why. It has a lot going on beneath the surface. I imagine many of us have hoped to escape into the safety of a movie screen, where at least a happily-ever-after is a possibility. The problem: any such escape is temporary, when you exit the theater, you find life waiting to chew you up again. What Binx Bolling discovers is that there are no ordinary lives, there are just lives in which all the meaning we need, or get, might rest in the most ordinary of things and days, and the people who are able to see beyond our surface and glimpse into our soul. A fabulous little book. The alienation of the main character is is very interesting, but in particular I felt that the solution to Kate's depression was what resonated with me the most. It was a feeling I had experienced in the past, while in a deep depression I just wished desperately that there was someone who would look out for me and tell me what to do. Tell me what I would do under normal circumstances and push me along to do it. It was an interesting thing to come across in this book. It is also one of the few books that has made me laugh out loud. Until my recent reading of The Moviegoer, I was a virgin to the Walker Percy experience. I came to this book because of years of glorious reviews and comments, his reputation of being a writer with a serious philosophical bent, and his 1962 National Book Award. I knew of Percy’s Southern origins, his agnostic upbringing, and about having lost his father to suicide when Walker was barely a teenager. Later I learned that just two years later, he was orphaned by his mother’s fatal car accident, one that Walker always believed was a suicide as well. Percy was a literary groundbreaker, a major influence on his fellow Southern writers with his estranged characters that were detached from much in their lives. With his early life, that disconnect isn’t hard to source. Now that I’ve read the book, I recognize the talent, found the characters interesting, was fascinated by their motivations that circled and sometimes slammed into each other, or simply headed away in different directions. All that said, I found myself detached from much of the book—possibly, it was the right book, just at the wrong time. Because of my age and life situation, I’m hip to the fact that books such as this won’t be able to wait on a shelf in my den, waiting for just the right time to read again—I’ve lost that life possibility. I would put on my “So Many Books, Too Little Time” T-shirt, if I only had one. [My trivia for this exact moment, that quote is surprisingly attributed to Frank Zappa.] Anyway, a widely acclaimed literary classic it is, but I’m moving on to my next book. This book probably felt deep and insightful in its day, but it did not connect with me. I know Walker Percy is hailed as one of the great Catholic writers, but I feel like the questions he addresses were better handled by Flannery O'Connor. Also, the ennui of successful white men leaves me cold in the year of Our Lord 2020. I'm not sorry to have read this, but I did not find it timeless. This book came out of nowhere to with the National Book Award in 1960. Percy was a doctor disqualified from medical practice because of tuberculosis. He had published a few philosophical musings in minor journals. He was the definition of obscure. His book wasn’t even nominated for the award. Nonetheless, a committee-member suggested The Moviegoer (a suggested read by a friend), and the rest is history. When Percy died in 1990, he was mentioned among America’s writing greats. What makes this book great? It’s a coming-of-age story in which Binx Boling, a stock broker in New Orleans, grows up. He begins the book alienated from a responsible lifestyle. He has casual sex and attempts to live a life of ease. He even romanticizes his female secretary – a vivid reminder that this book was published in 1960. Such an arrangement reminds the reader of a disoriented modern state in which success and failure can be intimately related to each other. Indeed, in Percy’s depiction, they often seem two sides of the same coin. Percy’s Roman Catholicism displays a view of salvation. Percy’s view differs from the predominantly Protestant culture of the American South where salvation is often equated with mere mental consent (assent?) to a set of beliefs. Instead, salvation for Bolling looks like assuming a life of responsibility. While the presentation of Bolling’s fiancee represents more of a stereotype of 1950s American culture, this responsibility indicates a coming of age for the protagonist. Overall, this story carries itself nicely. It begins in a disjointed manner and is hard to follow. It is much like Bolling’s life at that point. Yet it comes together beautifully as the story (and Bolling himself) evolves into someone new. No wonder critics rank it among the English Language’s top 100 novels of the twentieth century. It’s refreshing to read something that is essentially a spiritual quest (even a modern pilgrimage) that is consistent with the Christian tradition but is not centered around religious beliefs. Again, Percy’s view of salvation is something concrete and embodied. It is never preachy as Bolling’s immature views of God are even criticized. Those familiar with this type of American Gothic crossed with a redemption story will be reminded of the short stories of Flannery O’Connor (who shares Percy’s Catholicism). Faulkner’s Gothic style contains all of the disjointedness but none of Percy’s (and O’Connor’s) concretized and realistic redemption. As such, this readable work deserves its place in the English language’s literary canon. Walker Percy's 1960's National Book award winner about Binx Bolling living an odd premeditated alienated life in a New Orleans suburb where is goes movies and dates assistants on his solo stock broker office. His relations ship with his fragile cousin Kate and his family against the backdrop of upper class New Orleans and Mardi Gras is classic as he is in an ambiguous sea of ennui, romance alienation and redemption. Superb novel about alienation on mid 20 th century New Orleans . The protagonist pursues a life an a stock broker in the suburbs going to the movies as his sort of understated solo ritual of living through others lives . He is upper class and has a loving relationship with his female cousin who is mentally unstable . |

Current DiscussionsNonePopular covers

Google Books — Loading... Google Books — Loading...GenresMelvil Decimal System (DDC)813.54Literature American literature in English American fiction in English 1900-1999 1945-1999LC ClassificationRatingAverage: (3.66) (3.66)

|