Click on a thumbnail to go to Google Books.

|

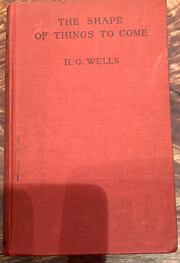

Loading... The Shape of Things to Come : the Ultimate Revolution (original 1933; edition 1935)by H. G. Wells

Work InformationThe Shape of Things to Come by H. G. Wells (1933)

No current Talk conversations about this book.   ) )A dystopian/utopian novel, written as a history book from the year 2106 and detailing the rise of a single world government. This is really good, despite what i will say about it's shortcomings, be assured that those are minor. As mentioned it is a history book and as such it can be quite dry with all of socio-economic talk etc. but its also really fascinating. Once i saw where it was going i thought it was going to turn out very silly and unrealistic. However when it got to the details it was remarkably detailed and authentic. Wells must have studied a lot of history books to be able to mimic them in this manner. The name dropping, references, argument and counter-arguments, every facet of this makes it seem real. BUT i do have a few gripes, one, its really long, a bit longer than it needed to be in my opinion although i do think the slowness of things added to the feeling of authenticity. Secondly i never understood how the organization's mentioned actually worked, in the details. How were people elected or promoted etc. it seemed a little hazy in that regard. Lastly but very much the major problem of this work is its sexism. I'm used to reading old books and good old-fashioned blatant (women should stay in the kitchen) sexism i can easily deal with, this was a little different. Women are almost entirely absent from this book, something which even the author acknowledges briefly but then excuses in the worst way. Wells is past the old fashioned sexism, he recognizes women as scientists, business people, artists and aviators so why are they so infrequent in this text you might ask? Well you see this is a history book, dealing with historically important people and according to Wells, women will NEVER stand out enough to be historically important. He also gives the secondary opinion that women don't WANT to be important. That they are naturally meek, submissive and unegotistical, instead of the power-hungry, backstabbing, narcissists we all know them to be, just like men. Its somewhat infuriating just because this book is so close to being perfect, if only Well's could have dragged himself a little further up the evolutionary ladder. Generally this writer finishes reading a book before reviewing it here. After struggling half way through this book I have decided to abandon this reading. Here is my thinking: First, this is a book of science fiction purporting to give the history of events from 1933 to the year 2106. This may have been interesting reading in prospective of that era, but now that half the course of time has run it is greatly confusing to read what Wells thought might happen while trying to keep tabs on what did happen. Second, the story deals heavily in propaganda, introducing the concept of "fake news." Since here in the first decades of the twenty-first century the major new stations engage largely in fake news, it is less than entertaining to read a book with such arrogant miss-reporting as its basic them. Thirdly, Wells is cheering for the wrong side. He is unabashedly liberal and continues a smear campaign against conservatism. He is too thoroughly modern. WARNING: This book may be injurious to your health! Liberalism is a mental disorder. One of Wells's last novels, this covers human history from 1933 to 2106. It's not really a novel in the conventional sense, but a history written from the perspective of the future, complete with a frame narrative explaining how it fell into the hands of Wells in 1933 so that he could publish it, which feels a little old-fashioned. (A lot of future narratives in the nineteenth century had this, like Shelley's The Last Man, Loudon's The Mummy!, Shiel's The Purple Cloud, Fawkes's Marmaduke, Emperor of Europe, but once the idea of the future narrative was firmly established around 1900, it largely vanished.) So it's the not most riveting reading-- this is an entirely different kind of science fiction to that which Wells started his career with novels like The Time Machine and The War of the Worlds. This is the fiction of ideas, not of sensations. If you're me, though, there's a lot of interesting stuff here. You get Wells's take on how future historians will view his own time (the first few chapters set things up with a discussion of the late Victorian era and the Great War) and then into the second World War, which Wells envisions as lasting from 1940 to 1950, followed by a devastating plague in 1956-57. From here, comes, of course, the World-State, that quixotic organization Wells spent so much of his late life advocating for. I don't love this book, but it's probably the most total depiction of the future-vision of the late Wells that I've read. Some random points of interest:

This is one of the best books I've ever read. One thing that impressed me was the interesting idea to narrate it as a story-within-a-story history book written in the future. However, the most interesting aspect of the book is the fact that many of the events that H. G. Wells described in the novel very closely match the way that events really did play out after it was written. Thinking about how reading this novel has affected me personally, I can say that I've sligthly lost track of which historical events were real and which ones were made up by Wells, since (as noted above) the novel very closely resembles reality. However, reading it definitely improved my English skills (I'm from Sweden). As a general assessment, I can say that this is a great book, and it's definitely worth reading. no reviews | add a review

Is contained inHas the adaptation

When a diplomat dies in the 1930s, he leaves behind a book of 'dream visions' he has been experiencing, detailing events that will occur on Earth for the next two hundred years. This fictional 'account of the future' (similar to LAST AND FIRST MEN by Olaf Stapledon) proved prescient in many ways, as Wells predicts events such as the Second World War, the rise of chemical warfare and climate change. No library descriptions found. |

Current DiscussionsNonePopular covers

Google Books — Loading... Google Books — Loading...GenresMelvil Decimal System (DDC)823.912Literature English & Old English literatures English fiction 1900- 1901-1999 1901-1945LC ClassificationRatingAverage: (3.46) (3.46)

Is this you?Become a LibraryThing Author. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||