Click on a thumbnail to go to Google Books.

|

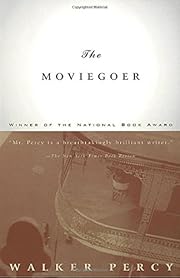

Loading... The Moviegoer (original 1961; edition 1998)by Walker Percy

Work InformationThe Moviegoer by Walker Percy (1961)

» 19 more

) )at first i was really liking this, the way that we see binx being lost in his life but finding his way through cinema but then it turned into something else and i myself was the one lost. i disliked the depiction of just about everyone (women, people of color) that he encountered and don't know if this is just another of the older books written by white men that i don't find any connection with, or if there was really just nothing to connect to. this won the national book award in 1960 (and was percy's first book), and i'm disappointed not to like it more. this description is so spot on though: "...I have only to hear the word God and a curtain comes down in my head." This is a singular book. Written in a laconic style that has the pacing of noir and the worldview of a Camus character but yet, infused with an easygoing sense of the speed of life in the suburbs of Louisiana . I liked all the descriptions of character and place. People aren't happy and that's a lot of what this is. People who are looking for a plot-driven story, please choose a different novel. Some have referred to this book as the first modern novel. Like a heaping plate of comfort food for me. Also contains one of my favorite quotes in a novel: “Whenever I feel bad, I go to the library and read controversial periodicals.” Hell yeah. But wait, there’s more. Binx Bolling doesn’t seem to be having a bad time of it, a young man successfully managing an office of the family brokerage firm in 1959/1960 New Orleans, having a series of dalliances with his secretaries, and going to a lot of movies. Only unlike most of us, he has the knowledge that such things are merely an effort to keep the existential despair at bay at the forefront of his mind. He instinctually feels the quote from Kierkegaard that is the novel’s epigraph: “the specific character of despair is precisely this: it is unaware of being despair”. Now he knows he is in despair and thus he is a bit better off by Kierkegaard’s reckoning, a step closer to the solution to it, but he is still a long way off a grounding of himself in religious faith. The forms and husk of religion are all around him of course, being plenty thick in the “Christ-haunted” but not “Christ-centered” South, as Flannery O’Connor memorably phrased it, but Kierkegaard too would have recognized the deadness of them. The best Binx can do is an awareness of “wonder” and a rejection of that which he feels too grossly ignores or obscures the wonder. His state of despair and inadequate search for resolution to it are best recognized for what they are by his step-cousin Kate, who is often in the grip of a strong depression, who seems possibly bipolar. Like recognizes like, in a manner. She tells him, “You remind me of a prisoner in the death house who takes a wry pleasure in doing things like registering to vote. Come to think of it, all your gaiety and good spirits have the same death house quality. No thanks. I’ve had enough of your death house pranks”. She tells him, “It is possible, you know, that you are overlooking something, the most obvious thing of all. And you would not know it if you fell over it.” Not that she knows what it is either, rather she’s given up the possible search: “Don’t you worry. I’m not going to swallow all the pills at once. Losing hope is not so bad. There’s something worse: losing hope and hiding it from yourself.” Binx, like Kate and Kierkegaard, understands the commonplace human tendency to hide our despair from ourselves, what he calls “sinking into everydayness”, even if the three of them (in the novel’s current moment at least) exist in pretty different places after similarly escaping it. Kierkegaard thinks he knows the answer. Kate thinks there is no answer. Binx, as befits a more modern day literary fiction hero, embraces uncertainty. Watching an apparently materially successful African-American man exiting church on Ash Wednesday, the ending day of the novel, ashes marked on forehead, he thinks I watch him closely in the rear-view mirror. It is impossible to say why he is here. Is it part and parcel of the complex business of coming up in the world? Or is it because he believes that God himself is present here at the corner of Elysian Fields and Bons Enfants? Or is he here for both reasons: through some dim dazzling trick of grace, coming for the one and receiving the other as God’s own importunate bonus? It is impossible to say.

Ironic but not cynical, complex without being abstruse, hopeful without sentimentality. Belongs to Publisher SeriesBibliothek Suhrkamp (903) Is contained inIs abridged inAwardsNotable Lists

A winner of the National Book Award, The Moviegoer established Walker Percy as an insightful and grimly humorous storyteller. It is the tale of Binx Bolling, a small-time stockbroker who lives quietly in suburban New Orleans, pursuing an interest in the movies, affairs with his secretaries, and living out his days. But soon he finds himself on a "search" for something more important, some spiritual truth to anchor him. Binx's life floats casually along until one fateful Mardi Gras week, when a bizarre series of events leads him to his unlikely salvation. In his half-brother Lonnie, who is confined to a wheelchair and soon to die, and his stepcousin Kate, whose predicament is even more ominous, Binx begins to find the sort of "certified reality" that had eluded him everywhere but at the movies. No library descriptions found. |

Current DiscussionsNonePopular covers

Google Books — Loading... Google Books — Loading...GenresMelvil Decimal System (DDC)813.54Literature American literature in English American fiction in English 1900-1999 1945-1999LC ClassificationRatingAverage: (3.66) (3.66)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||