Click on a thumbnail to go to Google Books.

|

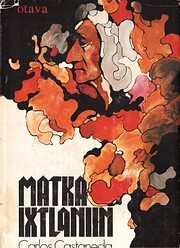

Loading... Matka Ixtlaniin : Don Juanin opit (original 1972; edition 1974)by Carlos Castaneda, Raija Mattila ((KAAnt.))

Work InformationJourney to Ixtlan by Carlos Castaneda (1972)

No current Talk conversations about this book. Si se lee como un libro más de superación personal mística, no importa. Su medio-filosofía new age me parece inofensiva. Sólo espero que nadie lo lea como un trabajo antropológico que representa las creencias y tradiciones de los pueblos indígenas. Porque, de verdad, esto tiene de literatura periodística-documental lo que yo de carmelita descalzo. Another slim volume, thick with impressions... Again one is struck by the very personal tone of Castaneda, as he allows don Juan to reveal the author's weaknesses and personal failures – and to be books about a sorcerer's (unwilling) apprentice, they show a very fragile and un-heroic apprentice. This is one of the aspects that makes it seem so genuine. no reviews | add a review

DistinctionsNotable Lists

Carlos Castanada was a student of anthropology when he met Don Juan Matus, a Yaqui shaman and the inspiration for Castanada's The Teachings of Don Juan. In this controversial work, Castanada relays his experiences being challenged by his mentor on his perception of the world and all living things in it. No library descriptions found. |

Current DiscussionsNonePopular covers

Google Books — Loading... Google Books — Loading...GenresMelvil Decimal System (DDC)299.7Religion Other religions Religions not provided for elsewhere Of North American OriginLC ClassificationRatingAverage: (3.7) (3.7)

Is this you?Become a LibraryThing Author. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Carlos Castaneda (1925-1998) wrote a series of twelve books about Mexican sorcery. They remain controversial because some think that Castaneda made it all up, but he maintained that this is a true account of his experiences as an apprentice and, later, a sorcerer.

“Journey to Ixtlan” is the third book in the series after “The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge” and “A Separate Reality: Further Conversations with Don Juan.” The first book describes Castaneda’s attempt in the early 1960s to study Native American use of psychotropic plants, working with don Juan Matus (1892?-1972?). The premise of “Journey” is that, by the early ’70s, Castaneda realized that he left out of the earlier books too much of what don Juan taught him, so he sets the record straight.

In his introduction, Castaneda claims that he never said that Juan Matus’ system of magic was linked to the traditions of the Yaqui tribe. It turns out to be a shared system that transcends tribal affiliation. Castaneda’s critics had pointed out that nothing in don Juan’s teachings fit with what is generally known about Yaqui tribal tradition. Castaneda’s rejoinder belies the fact that he did subtitle his first book “A Yaqui Way of Knowledge,” an implicit claim that don Juan’s teachings belong to this tribe. IMHO, Castaneda should have admitted that, when he published his first book in 1968, he made an honest if embarrassing mistake in attributing what don Juan taught him to Yaqui tradition.

A standard practice of anthropologists is to choose an informant from the community under study to help explain the customs and structure of the society from the inside. As “Journey” demonstrates, don Juan was an uncooperative informant, refusing to answer basic questions that might have cleared up the misunderstandings that bedevil Castaneda’s scholarship. Don Juan and Carlos (Castaneda is conventionally referred to by his first name when he becomes a character in his own books) are comically at cross purposes from the start. While the anthropologist is trying to recruit don Juan as his informant, the sorcerer is trying to recruit Carlos as his apprentice.

In hindsight, Carlos should have known that he was being recruited. He feels that don Juan is hectoring him about changing his lifestyle, and there is no reason for it other than that it is a necessary condition of their association and, besides, it is somehow for Carlos’ own good.

In Don Juan’s world, people not only must defend themselves from the familiar physical dangers – natural disasters, accidents, dangerous animals and bad people – but also from dangerous spirits and other unseen, malevolent forces. It turns out that there are no safe spaces in eternity (or “infinity” as Castaneda and don Juan call it). Interestingly, don Juan tames and uses “allies” or spirits similarly to ancient Greek and Persian magicians I have read about. Rituals and spells are means to gain control over spirits which are then used to enhance the magician’s power.

In don Juan’s universe, you don’t attain immortality by leading a good life but by leading an “impeccable” one, seeking knowledge and power, putting aside all considerations that are extraneous to that goal. Though there does seem to be some sort of karmic justice: it is better to be good than evil (For example, the sorcerer is said to be harmed by his own hatreds.), but being careless with the supernatural is worse than being a bad person.

“Journey” is about the preparations for leaving behind the mundane world. To expose oneself to supernatural power, which can be invigorating and terrifying all at once, the would-be sorcerer must learn to focus only on what matters, facing the fact of one's mortality and responsibility for one's own actions. Each chapter introduces a different component of this task. In exercising these disciplines, the line between the social, natural and supernatural blurs; the sorcerer must be just as inaccessible to people who would sap his vitality as to supernatural forces that would do the same or worse.

Along the way, don Juan evinces great flexibly in his teaching methods. When teaching Carlos about plants is not working, don Juan instead teaches him about hunting animals, to which the apprentice proves to be better suited. Don Juan is a master hunter, stalking prey with detailed knowledge of their habits, building traps from sticks and stones he finds in the semi-arid plains and mountains, cleaning and cooking what he catches. He is able to live off the land with an ease that would make any graduate of survival training jealous. He drops tidbits of wisdom such as that the hunter must have fewer bad habits than the prey; when animals elude otherwise powerful predators, it is often because the prey are less predictable than the predators.

The concept of “seeing” in the special sense in which a “man of knowledge” such as don Juan “sees” was introduced in “A Separate Reality” where don Juan taught Carlos that “seeing” is more than merely looking. In order “to see,” one must "not-do" or “stop the world,” that is, end the routine mental habits of perception handed to us since childhood. This is Carlos’ quest in this book as his incredulity is eroded by experiences with the supernatural. In one sequence, he spends a night surrounded by fog, rain, thunder and lightning, plus the utter blackness between lightning bolts. In the morning he awakens to find himself in a forest that is altogether different from the place where he fell asleep. Did don Juan carry him there? Was the dried meat he was eating the day before laced with a drug that made him imagine the place where he thought he fell asleep the previous night? Or did something magical actually take place?

Later in the book, don Juan turns Carlos over to don Genaro Flores, who was introduced in, “A Separate Reality.” Don Genaro makes Carlos begin to let go of his doubts. The distinction is made between Carlos’ body, which wises up under don Genaro’s manipulation, and his mind, which is still doubtful. When Carlos’ body is thus readied, don Juan orders him to go into the hills and not come back until his mind catches up with his body. Bravely, Carlos goes, despite having no idea what he must do. On his second day in the wilderness, he has three strange experiences: 1) he communicates telepathically with a friendly coyote; 2) he sees a phantom man out of the corner of his eye; and 3) he has a vision of the landscape covered with glowing lines.

Don Juan later tells him that the coyote is now Carlos’ special companion, which, he adds, is unfortunate because coyotes are tricksters and liars. Otherwise, Carlos is told that he did very well. His vision of the glowing filaments was a kind of "seeing." The “man” that he almost saw was an ally or spirit. The next step in Carlos’ apprenticeship will be to tackle the ally and acquire power from him. At the end of the book, Carlos must decide for himself whether he is ready or not to attempt this. Before he decides, don Genaro tells him a story about the first time that he overpowered an ally. Afterward, Genaro felt imbued with magical power, but the price he paid was never being able to find his way back to the town of Ixtlan, and that is the meaning of the title of this book. As Thomas Wolf might say, once you have changed, you can’t go home again. (