Abstract

Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 inhibitors (CDK4/6i) in combination with endocrine therapy improve the outcomes of patients with hormone-receptor (HR)-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer and can be used early as first-line treatment or deferred to second-line treatment1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Randomized data comparing the use of CDK4/6i in the first- and second-line setting are lacking. The phase 3 SONIA trial (NCT03425838) randomized 1,050 patients who had not received previous therapy for advanced breast cancer to receive CDK4/6i in the first- or second-line setting8. All of the patients received the same endocrine therapy, consisting of an aromatase inhibitor for first-line treatment and fulvestrant for second-line treatment. The primary end point was defined as the time from randomization to disease progression after second-line treatment (progression-free survival 2 (PFS2)). We observed no statistically significant benefit for the use of CDK4/6i as a first-line compared with second-line treatment (median, 31.0 versus 26.8 months, respectively; hazard ratio = 0.87; 95% confidence interval = 0.74–1.03; P = 0.10). The health-related quality of life was similar in both groups. First-line CDK4/6i use was associated with a longer CDK4/6i treatment duration compared with second-line use (median CDK4/6i treatment duration of 24.6 versus 8.1 months, respectively) and more grade ≥3 adverse events (2,763 versus 1,591, respectively). These data challenge the need for first-line use of a CDK4/6i in all patients.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

We are sorry, but there is no personal subscription option available for your country.

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

De-identified patient clinical data underlying the results reported in this Article will be made available to other researchers on reasonable request for academic use, within the limitations of the informed consent and the study’s consortium agreement. A detailed data proposal is required and will be considered on a case-by-case basis. Requests should be directed to BOOG study Center (info@boogstudycenter.nl) and will be reviewed by the study’s principal investigators. A response will be provided within 90 days. A signed data-access agreement with the sponsor is required before accessing shared data. The study protocol and SAP are provided with the paper.

References

Finn, R. S. et al. Palbociclib and letrozole in advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 1925–1936 (2016).

Hortobagyi, G. N. et al. Updated results from MONALEESA-2, a phase III trial of first-line ribociclib plus letrozole versus placebo plus letrozole in hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 29, 1541–1547 (2018).

Johnston, S. et al. MONARCH 3 final PFS: a randomized study of abemaciclib as initial therapy for advanced breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 5, 5 (2019).

Tripathy, D. et al. Ribociclib plus endocrine therapy for premenopausal women with hormone-receptor-positive, advanced breast cancer (MONALEESA-7): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 19, 904–915 (2018).

Cristofanilli, M. et al. Fulvestrant plus palbociclib versus fulvestrant plus placebo for treatment of hormone-receptor-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer that progressed on previous endocrine therapy (PALOMA-3): final analysis of the multicentre, double-blind, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 17, 425–439 (2016).

Slamon, D. J. et al. Phase III randomized study of ribociclib and fulvestrant in hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative advanced breast cancer: MONALEESA-3. J. Clin. Oncol. 36, 2465–2472 (2018).

Sledge, G. W. et al. MONARCH 2: abemaciclib in combination with fulvestrant in women with HR+/HER2− advanced breast cancer who had progressed while receiving endocrine therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 35, 2875–2884 (2017).

van Ommen-Nijhof, A. et al. Selecting the optimal position of CDK4/6 inhibitors in hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer—the SONIA study: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer 18, 1146 (2018).

Sledge, G. W. et al. The effect of abemaciclib plus fulvestrant on overall survival in hormone receptor-positive, ERBB2-negative breast cancer that progressed on endocrine therapy-MONARCH 2: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 6, 116–124 (2020).

Hortobagyi, G. N. et al. Overall survival with ribociclib plus letrozole in advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 942–950 (2022).

Slamon, D. J. et al. Overall survival with ribociclib plus fulvestrant in advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 514–524 (2020).

Lu, Y. S. et al. Updated overall survival of ribociclib plus endocrine therapy versus endocrine therapy alone in pre- and perimenopausal patients with HR+/HER2− advanced breast cancer in MONALEESA-7: a phase III randomized clinical trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 28, 851–859 (2022).

Gradishar, W. J. et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Breast cancer, Version 4.2023. J. Natl Compr. Cancer Netw.21, 594–608 (2023).

Kümler, I., Knoop, A. S., Jessing, C. A., Ejlertsen, B. & Nielsen, D. L. Review of hormone-based treatments in postmenopausal patients with advanced breast cancer focusing on aromatase inhibitors and fulvestrant. ESMO Open 1, e000062 (2016).

Yang, C. et al. Acquired CDK6 amplification promotes breast cancer resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors and loss of ER signaling and dependence. Oncogene 36, 2255–2264 (2017).

Park, Y. H. et al. Longitudinal multi-omics study of palbociclib resistance in HR-positive/HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer. Genome Med. 15, 55 (2023).

Gyawali, B. et al. Problematic crossovers in cancer drug trials. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 20, 815–816 (2023).

Spring, L. M. et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 inhibitors for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: past, present, and future. Lancet 395, 817–827 (2020). A.

Cherny, N. I. et al. A standardised, generic, validated approach to stratify the magnitude of clinical benefit that can be anticipated from anti-cancer therapies: the European Society for Medical Oncology Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (ESMO-MCBS). Ann. Oncol. 26, 1547–1573 (2015).

G-standaard, Tarieven Januari (Z-index, 2023).

G-standaard, Tarieven Januari (Z-index, 2019).

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Part D Spending by Drug (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, accessed 8 May 2024); data.cms.gov/summary-statistics-on-use-and-payments/medicare-medicaid-spending-by-drug/medicaid-spending-by-drug.

Johnston, S. et al. Abemaciclib as initial therapy for advanced breast cancer: MONARCH 3 updated results in prognostic subgroups. NPJ Breast Cancer 7, 80 (2021).

Rugo, H. S. et al. Palbociclib plus letrozole as first-line therapy in estrogen receptor-positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative advanced breast cancer with extended follow-up. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 174, 719–729 (2019).

Di Lauro, V. et al. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients treated with CDK4/6 inhibitors: a systematic review. ESMO Open 7, 100629 (2022).

Turner, N. C. et al. Overall survival with palbociclib and fulvestrant in advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 1926–1936 (2018).

Finn, S. R. et al. Overall survival (OS) with first-line palbociclib plus letrozole (PAL+LET) versus placebo plus letrozole (PBO+LET) in women with estrogen receptor–positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative advanced breast cancer (ER+/HER2−ABC): Analyses from PALOMA-2. J. Clin. Oncol. 40, LBA1003 (2022).

André, F. et al. Alpelisib for PIK3CA-mutated, hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 1929–1940 (2019).

Turner, N. C. et al. Capivasertib in hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 2058–2070 (2023).

Bidard, F. C. et al. Elacestrant (oral selective estrogen receptor degrader) versus standard endocrine therapy for estrogen receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative advanced breast cancer: results from the randomized phase III EMERALD trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 3246–3256 (2022).

Garcia-Fructuoso, I., Gomez-Bravo, R. & Schettini, F. Integrating new oral selective oestrogen receptor degraders in the breast cancer treatment. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 34, 635–642 (2022).

Woodford, R. et al. Validity and efficiency of progression-free survival-2 as a surrogate end point for overall survival in advanced cancer randomized trials. JCO Precis. Oncol. 8, e2300296 (2024).

European Medicines Agency. Appendix 1 to the Guideline on the Evaluation of Anticancer Medicinal Products in Man (EMA, 2012).

Fojo, T. & Simon, R. M. Inappropriate censoring in Kaplan-Meier analyses. Lancet Oncol. 22, 1358–1360 (2021).

Gyawali, B. et al. Biases in study design, implementation, and data analysis that distort the appraisal of clinical benefit and ESMO-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (ESMO-MCBS) scoring. ESMO Open 6, 100117 (2021).

Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. Guideline on the Choice of the Non-Inferiority Margin (EMA, 2005).

Tannock, I. F. et al. The tyranny of non-inferiority trials. Lancet Oncol. 25, e520–e525 (2024).

Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. Concept Paper for the Development of a Guideline on Non-Inferiority and Equivalence Comparisons in Clinical Trials (EMA, 2024).

André, F. et al. Alpelisib plus fulvestrant for PIK3CA-mutated, hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2-negative advanced breast cancer: final overall survival results from SOLAR-1. Ann. Oncol. 32, 208–217 (2021).

Robson, M. E. et al. OlympiAD final overall survival and tolerability results: Olaparib versus chemotherapy treatment of physician’s choice in patients with a germline BRCA mutation and HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 30, 558–566 (2019).

Casparie, M. et al. Pathology databanking and biobanking in The Netherlands, a central role for PALGA, the nationwide histopathology and cytopathology data network and archive. Cell Oncol. 29, 19–24 (2007).

Eisenhauer, E. A. et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 45, 228–247 (2009).

Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v.4.0 (National Cancer Institute, 2010).

Brady, M. J. et al. Reliability and validity of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-breast quality-of-life instrument. J. Clin. Oncol. 15, 974–986 (1997).

Eton, D. T. et al. A combination of distribution- and anchor-based approaches determined minimally important differences (MIDs) for four endpoints in a breast cancer scale. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 57, 898–910 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patients who participated in this trial, as well as their families; all members of the steering committee and the study staff at all 74 hospitals of the SONIA trial; the independent Data Safety Monitoring Board; the Dutch Breast Cancer research Group (BOOG) for their support and sponsorship; the registration team of the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organization (IKNL) for the collection of data for the Netherlands Cancer Registry; and all data managers for data collection throughout the trial. The Dutch Nationwide Pathology Databank (Palga) provided histopathology data. The Dutch Breast Cancer Association (BVN) was involved in the development and the execution of the trial. The trial was funded by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research (ZonMw) and Development and Dutch Health Insurers (ZN).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

A.J., G.S.S. and I.R.K. initiated the study. A.J., G.S.S., I.R.K. and V.v.d.N. designed the study with support from the study steering committee and The Dutch Breast Cancer Association (BVN). C.G.P. as director of BVN was involved in the development and the execution of the trial. A.E.v.L.-S. as director of the Dutch Breast Cancer research Group (BOOG) was involved in the project administration, funding acquisition and in the development and execution of the trial. A.B., A.v.O.-N., A.H.H., A.J., C.v.S.-v.d.M., C.S.T.-v.D., G.S.S., I.R.K., J.B.H., J.T., K.B., L.C.H., N.W., P.C.d.J., Q.C.v.R.-S. and S.V. contributed to recruitment of patients. A.C.P.S. and L.M. contributed to data collection and validation on behalf of the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organization (IKNL). V.v.d.N. was the trial statistician. A.v.O.-N., N.W. and V.v.d.N. accessed and verified the data and contributed to the data analysis. H.M.B. contributed to the data analysis of the health-related quality-of-life and costing. A.J., G.S.S. and I.R.K. contributed to supervision of the study. A.J., A.v.O.-N., G.S.S., I.R.K. and N.W. wrote the initial draft of the article and decided to submit the manuscript. All of the authors participated in interpretation of the data and drafting of the manuscript. All of the authors reviewed and approved the final, submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

G.S.S. reports institutional research support from Agendia, AstraZeneca, Merck, Novartis, Roche and Seagen; and consultancy for Biovica, Novartis and Seagen. H.M.B. received grants from CADTH, ZIN and Medical Delta; and participated in a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for Pfizer. A.H.H. received consulting fees from Gilead and Lilly; and received payment or honoraria from Lilly. Q.C.v.R.-S. has participated in a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for Roche. I.R.K. reports institutional research grant support from Novartis and Gilead. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Suzette Delaloge, Debu Tripathy and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

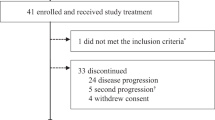

Extended Data Fig. 1 Trial profile.

The figure presents an overview of the course of the trial for all study participants. Of note, the number of deaths reported here are only those deaths that were reported to be the reason for discontinuation of first- or second-line therapy (i.e., patients who died in the absence of objective disease progression while on study treatment). The number of PFS2 events (n = 591) is different from the number of patients that discontinued second-line endocrine therapy (n = 502), since not all patients with a PFS2 event discontinued second-line treatment and not all patients who discontinued second-line treatment experienced a PFS2 event. NSAI, non-steroidal aromatase inhibitor; CDK4/6i, cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 inhibitor.

Extended Data Fig. 2 PFS1 in ITT population.

Kaplan–Meier plots for PFS after one treatment line (PFS1) in the CDK4/6i-first and CDK4/6i-second group in the ITT population. Cox proportional hazard models were used to calculate hazard ratios between the study groups and were stratified according to the stratification factors used in randomization. The difference was assessed using the stratified log-rank test. P values are two-sided. Events, number of PFS1 events; n, number of patients randomized.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Table 1 (Overview protocol amendments), Supplementary Table 2 (Overview SAP adjustments), List of members of the SONIA consortium, Trial protocol (the first approved protocol version 1.2), Trial protocol (the last approved protocol version 1.11), and Statistical analysis plan.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Sonke, G.S., van Ommen-Nijhof, A., Wortelboer, N. et al. Early versus deferred use of CDK4/6 inhibitors in advanced breast cancer. Nature (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08035-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08035-2